Paul Elie, Jean Bethke Elshtain, and Robin Lovin

Moral Man and Immoral Society: Rediscovering Reinhold Niebuhr

We explore the ideas and present-day relevance of 20th century theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, an influential, boundary-crossing voice in American public life. Niebuhr created the term “Christian realism:” a middle path between religious idealism and arrogance. Exploring his wide appeal, three distinctive voices describe Niebuhr’s legacy and ask what insights he brings to the political and religious dynamics of the early 21st century.

Guests

Jean Bethke Elshtain was an author and Laura Spelman Rockefeller Professor of Social and Political Ethics at the University of Chicago Divinity School.

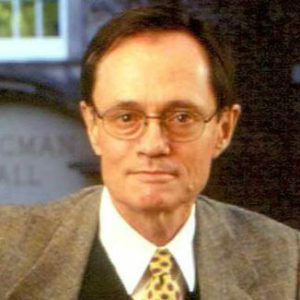

Robin Lovin is Cary M. Maguire University Professor of Ethics at the Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University, and the author of Reinhold Niebuhr and Christian Realism.

Paul Elie a senior fellow in Georgetown’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. He is the author of The Life You Save May Be Your Own and Reinventing Bach, and of essays and articles for the Atlantic, New York Times, Vanity Fair, Commonweal, and other periodicals. He blogs regularly at Everything That Rises.

Transcript

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, we pursue enlarged perspective on war, nation-building, and religion and politics through the ideas of Reinhold Niebuhr. He’s recently been rediscovered by an unlikely array of pundits and politicians. Niebuhr’s penetrating analysis of human nature shaped his approach to 20th-century foreign policy and might reframe ours.

MR. PAUL ELIE: The very idealism that has animated so many good things in the history of this country also lead us to be arrogant, lead us to be insensitive to the cultures of other peoples, lead us to overestimate the ability to get things to go our way. Our virtues and our vices are inextricably joined. It’s a religious insight that’s being applied in a political situation.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. This hour, we pursue enlarged perspective on war, nation-building, and religion and politics through the ideas of Reinhold Niebuhr. This 20th-century theologian is being invoked by commentators on the right and the left, as well as politicians from Barack Obama to John McCain. So who was he? And how might his very way of thinking reframe 21st-century confusions?

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. Today, “Moral Man and Immoral Society: Rediscovering Reinhold Niebuhr.”

Reinhold Niebuhr was born in 1892, the German-American son of a Protestant minister. As a young man, he pastored a church in Henry Ford’s Detroit, where he became a force for labor rights and race relations. On the eve of the Great Depression in 1928, he accepted an invitation to teach social ethics at Union Theological Seminary in New York City. There, he stayed for three decades. Niebuhr wrote books with grand, evocative titles: Moral Man and Immoral Society, The Irony of American History, The Nature and Destiny of Man. That book begins, “Man has always been his own most vexing problem.” Human nature, he explained, would always complicate even our highest ideals and our greatest accomplishments. This insight necessitates a humility in every human endeavor, especially faith and politics.

Presidents and Supreme Court judges, social activists, and poets sought Reinhold Niebuhr’s counsel. He was unclassifiable, ideologically. Or rather, he was alternately called a liberal, a hawk, a reactionary, a pacifist. Martin Luther King quoted Niebuhr in his Letter from Birmingham Jail. And Niebuhr drafted a prayer during World War II that was later adapted as the Serenity Prayer of Alcoholics Anonymous. He was as famous for essays on foreign policy as for his Sunday sermons. He preached sober realism in the early and middle decades of the 20th century as idealism and can-do optimism flourished in American culture and American churches despite violence and tyranny abroad.

MR. REINHOLD NIEBUHR: (archival audio) Have you studied the history of our Puritan fathers in New England? I don’t want to engage in the ordinary, rather cheap strictures against our Puritan fathers because there were some very great virtues and graces in their life. But I’ve become convinced as I read American history that this represents the real defect in our Puritan inheritance — the doctrine of special providence. These Puritan forefathers of ours were so sure that every rain and that every drought was connected with the virtue and vice of their enterprise, that God always had his hand upon them to reward them for their goodness and to punish them for their evil.

This is unfortunate. And it’s particularly unfortunate when a religious community develops in the vast possibilities of America, where inevitably the proofs of God’s favor will be greater than the proof of God’s wrath. This may be the reason why we are so self-righteous. This may be the reason why we still haven’t come to terms in an ultimate religious sense with the problem of the special favors that we enjoy as a nation against the other nations of the world.

MS. TIPPETT: My first guest this hour, Paul Elie, writes about Niebuhr in the current issue of The Atlantic. He spent several months sifting through the somewhat confusing present revival of Niebuhr’s legacy across the U.S. political spectrum. Paul Elie is an editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. And he’s explored the convergence of literature, social activism, and faith as a journalist and author. I asked how he would begin to characterize Reinhold Niebuhr’s importance.

MR. ELIE: Reinhold Niebuhr was one of the most significant religious thinkers this country has produced. That’s how he strikes me. Of course he had a political role, he taught, he preached; but his books, for me, are on the short shelf of books that feel permanent even though they are distinctly American and modern.

MS. TIPPETT: I think, interestingly, maybe ironically, and that was one of his favorite words, his best-known words are probably the Serenity Prayer. And the original prayer he drafted was, “God, give us grace to accept with serenity the things that cannot be changed, courage to change the things that should be changed, and the wisdom to distinguish the one from the other.” And it’s kind of fascinating to note that although we think of that as being connected with the 12-Step Movement and Alcoholics Anonymous, it was written on a card that was carried in the pocket of soldiers in World War II. And you have such an interesting line in your piece in The Atlantic Monthly. You wrote, “More than a prayer, this was Niebuhr’s prescription for action in the new era waiting on the far side of the war.”

MR. ELIE: I think the prayer is actually a pretty effective distillation of the Niebuhrian outlook. Accepting the things that one cannot change, you have to accept human nature, human frailty, the limits of the human life, the fact that there are unforeseen consequences to our actions.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. ELIE: The courage to change the things that can be changed — that’s a formula for intervention in the world for trying to improve the plight of workers or the political arrangements in Europe or the situation of blacks in the South.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. ELIE: And the wisdom to distinguish the one from the other — that’s the whole ballgame for Niebuhr. How do you distinguish the things you can change from the things you can’t change? The fact that that’s difficult is why there are so many divergent interpretations of Niebuhr’s work. But his work inspires us to make that commitment distinguishing the one from the other. That’s what the moral life is about.

MS. TIPPETT: And you do note, and this is really the occasion for your article, that in think tanks, and on the op-ed pages, and on divinity school quadrangles, Niebuhr’s ideas are more prominent than at any time since his death in 1971. I mean, how did you start to trace that and to explain it, to understand it?

MR. ELIE: Well, I think that it first struck me because I know Reinhold Niebuhr’s daughter, Elisabeth Sifton. She’s a book publisher…

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. ELIE: …who works for the same company that I work for. So through my long association with Elisabeth, I thought of Reinhold Niebuhr as an actually, existing person whose daughter would notice his name cropping up in the papers. The next thing I noticed was that the references to him didn’t really add up.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. ELIE: We had people who would be at each other’s throat, both saying they are Niebuhrians.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. ELIE: I’d scratch my head and open the books.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. For example, what — yeah.

MR. ELIE: Well, I had noticed something that David Brooks had written in The Atlantic, the very magazine where my own article appeared. I followed the track of his article back to another magazine I know well, First Things. I had reason to respect this thinker. And then I was fairly surprised by what he had to say about what Niebuhr’s take on the war on terror would have been.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. ELIE: There’s plenty in Niebuhr’s writings that support a vigorous prosecution of a necessary war. It’s the tone that surprised me. Niebuhr made his mark, if you will, as a political thinker, by advocating for American intervention in Europe in the 1930s. He was very much for it. At the same time, he advocated for war with a kind of grief. There’s pain and agitation in his writings in a way that I don’t think I was seeing at that time in their writing about the need to go to war in Iraq. The tone, the emotional content of it was very different, and that struck me.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. I mean, I have also noticed that Niebuhr, it seems to me, increasingly, there’s kind of an escalation of mentions of him. And you pull that together, I mean, it’s not just David Brooks. It’s Eliot Spitzer, Barack Obama. It’s John McCain, Arthur Schlesinger Jr. before he died. He knew Niebuhr and was close to him. And shortly before his death, Schlesinger wrote in a piece in The New York Times, again sort of calling for Niebuhr’s influence, for an attention to Niebuhr’s voice. You know, it’s interesting, isn’t it?

MR. ELIE: It sure is. And you ask yourself why. I wouldn’t say there’s a single reason why.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. ELIE: But I think there’s a yearning in our culture for people whose basic commitments are prior to politics, who have a frame of reference that’s larger than politics, which isn’t to say simply that they don’t, favor one party or the other, but that they have a vocabulary, a frame of reference that helps to explain their political commitments instead of the political commitments coming first. Niebuhr is as good an example I can think of that kind of person. And I think that’s been very attractive to people.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. You know, much is written in religious circles about the fact that Niebuhr held that religion was both necessary and dangerous. And I think that the same is true for him about politics, that politics is necessary and dangerous. I think of that, what you just described, that even though politics is front and center in how we navigate and negotiate important issues of our time, I agree with you, there are some sense of the limits of politics, that it still can’t explain or frame perhaps what is most important in these conflicts.

MR. ELIE: Myself, I don’t think politics can explain what’s most important. Politics is a practical business. And you can run on a platform of cleaning up Washington, but it’s only going to get so clean, because the nature of politics and the nature of the human person is that we compromise, we do things for mixed motives, that even our noblest ends are achieved with aggression and coercion and self-interest along the way. On some level, I think most of us know that. But Niebuhr’s gift was to express that.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. ELIE: And to express in the way that felt as complex as life actually is.

MS. TIPPETT: Author and editor Paul Elie. In my experience as an interviewer, Reinhold Niebuhr has been cited as an influence by a wide array of thinkers. Invoking him tends to add complexity, even struggle, to religious and political positions.

Here’s a voice from the Speaking of Faith archives, Evangelical political analyst Michael Cromartie, who we interviewed during the 2004 election campaign. Cromartie was reflecting on Reinhold Niebuhr’s ideas as he took a self-critical look at the conservative Christian turn to politics to address moral concerns.

MR. MICHAEL CROMARTIE: When you’re trying to raise kids in this culture of all manner of violence and, let’s just say, moral relativism all around, you become a little bit concerned about, well, what can our political process do to sort of at least abate some of these problems? Now, by the way, I just want to say that it’s not the case that politicians can do a whole lot about all of this except in the most symbolic ways. I know it’s — I just want to say that sometimes religious conservatives have an over-inflated view of the, of what politics can do to reshape a culture. It’s what the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr said, politics is the art of finding approximate solutions to basically insoluble problems. Working for a certain amount of justice, a certain amount of order, but it will never be Utopian.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. This hour, “Moral Man and Immoral Society: Rediscovering Reinhold Niebuhr.”

In his current article in The Atlantic, Paul Elie describes the difficulty of translating Niebuhr’s ideas in today’s partisan context. For example, Niebuhr was associated with conservative anti-communism after World War II. But he also helped to found the liberal lobbying organization Americans for Democratic Action, together with Eleanor Roosevelt, John Kenneth Galbraith, and Hubert Humphrey.

MS. TIPPETT: The very notion of liberalism had different connotations for him than it gained in U.S. culture by the end of the 20th century.

MR. ELIE: Not so long ago, even secular liberals recognized the biblical flavor of a lot of early American history. If you listen to an old Pete Seeger record, he’ll have the word “hallelujah” used in the songs or he’ll sing a song about Jericho, even though he was a member of the Communist Party.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. ELIE: It was just understood that that was part of our American heritage. And I’m not so sure that’s the case today.

MS. TIPPETT: But I think that what’s also revealed in just stepping back and taking a longer view of time is how 21st-century liberals operate on some assumptions as though these are, you know, these are nuggets of wisdom that have come down across the ages. And, in fact, there’s a distance between them and what liberalism meant, at least as embodied in many people, including Reinhold Niebuhr, even in the mid-20th century.

MR. ELIE: That’s right. If you think of what is considered the high point of American liberalism, I would say it has to be the Civil Rights Act in 1965. You had an activist, Democratic president, pushing through legislation that was going to make major social changes and expand freedom, which was the root of the liberal project. And at the same time, the Civil Rights Act was the culmination of the greatest religious episode in the history of this country.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. ELIE: The Civil Rights movement as led by Dr. King, and with people like Niebuhr and Rabbi Heschel at the same time. So those two causes at certain points in our history were one. And there are a lot of people in both the religious world and the liberal world who are saddened by the fact that those two movements have been torn asunder. I don’t know what to do about it. But it’s certainly true.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. The words moral and immoral — those words are used and bandied about a lot in the early 21st century in U.S. politics and American life. And I wonder if they mean at all the same thing when we use them and Niebuhr used them? You have a really nice concise sentence: “The irony of American history,” as Niebuhr explained it, is ‘Our virtues and our vices are inextricably joined.'” I mean that’s also such an important point for him, isn’t it, that morality and immorality are not these fixed, separate qualities that never meet.

MR. ELIE: I can’t remember which ancient Christian sage said that good and evil are joined at the spine, something like that, though. What Niebuhr meant is that we can’t separate out our virtues and our vices. The very idealism that has animated so many good things in the history of this country also lead us to be arrogant, lead us to be insensitive to the cultures of other peoples, lead us to overestimate the ability to get things to go our way, and so on. Our virtues and our vices are inextricably joined. It’s a religious insight that’s being applied in a political situation.

MS. TIPPETT: I think one reason Niebuhr is intriguing to us now also is that he was such a bridge person, a crossover person between religious thinkers and actors, and secular thinkers and actors.

MR. ELIE: I think that’s true. And I was thinking about this over the past few days in connection with Niebuhr’s insights about purity. His realism was grounded in his feeling that human nature is necessarily impure. And when you try to purify society, those people better watch out because that’s when things get dangerous, whether it’s reforming Christians who are trying to purify things, or reforming secularists who are trying to purify things. The Niebuhrian position would be religion never was altogether pure and never will be. Let’s start from a different premises.

MS. TIPPETT: Have you thought about how Niebuhr might react to the religiosity of our time, the way in which — I’m saying that and I’m realizing that was probably after he died that religion really retreated from the public sphere, and yet it’s back out on the surface in many forms. And it’s alarming to many intellectuals who, I think, are the same kinds of people we’re talking about who would have found Niebuhr a very intriguing and helpful figure 50 years ago.

MR. ELIE: There was a lot of religious strife in Niebuhr’s time as well. And it’s easy to forget that, to assume that his time was one in which established religion had a comfortable place in the public life. And religious figures could act without fear of reprisal, et cetera and so forth. The religion was deep, historically committed.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. ELIE: The religiosity of the South was such that H.L. Mencken could sneer at it in the Bible Belt. Roman Catholics at the time were so distrustful of the public school system that they refused to send their children to it.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. ELIE: Certainly, American Jews didn’t suffer like the Jews of Europe, but this was not an altogether hospitable place for them. So my point is that in retrospect, it looks as though that was a solidly religious age, but these things are being contested in every age. And Niebuhr’s gift was to not get stuck on that…

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. ELIE: …to get on with his work without trying to fix the whole religious situation of America single-handedly.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, to be a constructive voice nevertheless.

MR. ELIE: And to write work that wasn’t so rooted in his age that it couldn’t transcend the age and speak to ours as well.

MS. TIPPETT: Elie is a senior editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux Publishers.

This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, we’ll think about the insights Reinhold Niebuhr might have for the war in Iraq and the U.S. role in the emerging 21st-century world.

We’ve combed boxes of Reinhold Niebuhr’s personal archives at the Library of Congress and produced an interactive timeline on our Web site with actual photos of Niebuhr’s personal correspondents. These letters illustrate Niebuhr’s friendships with public figures like the Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter, the poet W.H. Auden, Dr. Albert Schweitzer, and many others.

And be sure to subscribe to our podcast and e-mail newsletter to download my interviews with all the guests in this program as well as Reinhold Niebuhr’s daughter, Elisabeth Sifton. All this and more at speakingoffaith.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Moral Man and Immoral Society.” We’re exploring the ideas and present-day resonance of the theologian and public intellectual Reinhold Niebuhr. He’s recently been rediscovered by thinkers and politicians on the right and the left.

For decades, one observer has noted, Reinhold Niebuhr defined how Americans with realistic faith would deal with the world. In his 1932 book, Moral Man and Immoral Society, Niebuhr applied his analysis of the human condition to societies and nations. Individuals, he said, may strive to be moral. But collectively, human beings are compromised and prone to immorality, even evil. Niebuhr’s complex reasoning about the world, God, and human nature made him hard to classify ideologically. He identified for many years as a pacifist, then vigorously argued for American engagement in World War II. He became a staunch cold warrior, but he rejected the war in Vietnam as an extension of that conflict.

He once wrote that “civilization depends upon the vigorous pursuit of the highest values by people who are intelligent enough to know that their values are qualified by their interests and corrupted by their prejudices.”

MR. NIEBUHR: (archival audio) Where has there ever been a conflict in the human community where we have not felt that we could not fight the battle if the Lord were not on our side? Though, as Abraham Lincoln said, we did not frequently enough ask the question of whether we were on the Lord’s side. These are natural religious instincts, natural efforts to close the great structure of life’s meaning prematurely.

MS. TIPPETT: My next guest, the University of Chicago political theorist Jean Bethke Elshtain, was an early proponent of U.S. military engagement in response to the September 11th terrorist attacks. In her 2003 book, Just War Against Terror: The Burden of American Power in a Violent World, Jean Bethke Elshtain devoted a chapter to the father of “just war theory,” Saint Augustine, together with Reinhold Niebuhr.

I asked her in 2004, how she would characterize Niebuhr as a thinker with enduring wisdom on the reality and morality of war.

DR. JEAN BETHKE ELSHTAIN: Right. Well, what comes to mind is a person of great seriousness of purpose who ongoingly engaged the struggles of his time, didn’t retreat from them, immersed himself fully in them without becoming entirely reconciled to them. So I think that insistence that we confront the harsh realities of our time, that we think seriously about them as Christians, that insistence is really the heart of the matter. And I would add here also the recognition that human beings are finite, incomplete, frail creatures, and that the politics that we create is bound to be marked by our own finitude.

MS. TIPPETT: So a great deal of what Niebuhr struggled with and the sort of crucible in which he formed a lot of his great theology had to do with world events and was in wartime.

DR. ELSHTAIN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: A very different kind of war in a different era of history. But I think what’s maybe most interesting to get at is not so much asking where would Niebuhr come down on this current war, but how would he think it through. Now, you obviously have your opinions and positions, but, you know, I’d really like to start at getting at that by how did you think about how Niebuhr would come at this, what ideas and questions he would bring to this current war that we have?

DR. ELSHTAIN: Well, he would certainly begin with those basic recognitions of human sinfulness, the reality of evil, the need to punish and restrain those who are determined to harm the innocent, the innocent being those in no position to defend themselves. That, I think, would be the basis of his thinking, together with real concerns about trying to do more than you reasonably can, even in restraining and punishing evil. I think he would insist that evil be confronted, but at the same time that we not be over ambitious in that confrontation and try to bring about results that are beyond our capacities and thereby perhaps bringing about an outcome that is quite different from the one that we had too optimistically anticipated.

So I think that he would approach this with a great deal of gravity and solemnity and recognition of the play of forces. I mean, people, I think, forget that Niebuhr was very much in the mix of figures who were thinking about international relations and about how states behave.

MS. TIPPETT: Diplomats and politicians as well as religious thinkers.

DR. ELSHTAIN: Exactly. He’s in that mix. And they’re looking to him, in part, as one of their own, someone who brought a particular cluster of recognitions but was very much a realist. So I must say that I go back and forth on how Niebuhr would finally situate himself. But I think that’s how he would start to think about both the war against terrorism and the current Iraq conflict.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, just a moment ago when you were describing his thought, I heard you using words and ideas that would be cautionary for people who take both sides of this war.

DR. ELSHTAIN: That’s right.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, on the one hand that there is such a thing as evil that sometimes must be confronted, must be named and punished. On the other hand, that there’s always this danger of hubris.

DR. ELSHTAIN: Indeed.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s this great, well, I think this very compelling quote from Niebuhr, there’s so many of them, aren’t there?

DR. ELSHTAIN: There are.

MS. TIPPETT: He said, “The New Testament does not envisage a simple triumph of good over evil in history. It sees human history involved in the contradictions of sin to the end.”

DR. ELSHTAIN: Absolutely. So how do you work out the tension? And it’s a never-ending tension.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. ELSHTAIN: It will persist until the end time between power and the good and how we try to make a world that is less brutal and less evil than the one that we’re in with no presupposition that there will be a culminating moment when all will be well.

MS. TIPPETT: Jean Bethke Elshtain. Here’s a segment from the Speaking of Faitharchives with former war correspondent Chris Hedges. He described how Niebuhr’s thought was shaping his attitude towards American military engagement in Iraq.

MR. CHRIS HEDGES: You know, Niebuhr is often described as a Christian realist, but he ardently opposed the Vietnam War. So I think Niebuhr understood human societies and he understood human nature and he understood that to make moral choice is not between moral and immoral but between immoral and more immoral. And when you don’t want to be tainted, and I think some pacifists can go this route in the same way that cynics do, you don’t make choice, you know? Because we live in a fallen world, because we often don’t get to pick between good and evil but between evil and more evil, you know, we in the end have to be tainted. It’s why Niebuhr wrote that when we make a decision — because we don’t know the will of God, we often don’t know the consequences of our actions however well-intentioned — we must always ask for forgiveness and be very frightened of hubris. And hubris, as the ancient Greeks know, can destroy us.

MS. TIPPETT: And one of Niebuhr’s favorite words, I think, or one of his central concepts was paradox.

DR. ELSHTAIN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And he used words like paradox and irony. And it seems to me that that falls away completely when you reduce everything to black and white, good and evil, an either/or choice. Talk about how you understand and how he used and lived with a concept like paradox and how you might offer up, that up to our public life.

DR. ELSHTAIN: Well, I think the paradox begins for a Christian theologian like Niebuhr with the fact that we have Christ and we have culture. That’s the first paradox that his brother H. Richard Niebuhr wrote a famous book on, Christ and Culture. Christ’s kingdom is not of this world and yet Christians are called to try to achieve some relative justice, some approximation of that kingdom on this earth. There’s…

MS. TIPPETT: And then part of that is also not, it’s not a sense of futility but just…

DR. ELSHTAIN: Not at all.

MS. TIPPETT: …just knowing that things will go wrong, being realistic about that, right?

DR. ELSHTAIN: Absolutely. It’s being realistic, being aware of the shortcomings of what we can do. But that is not an invitation to quiescence or to a kind of sectarian retreat. That’s an attitude that Niebuhr would find troubling, even offensive, because it neglects the responsibility that is ours to care for others. The question, you know, ‘Who is my brother?’ ‘Who is my sister?’ for Niebuhr is always a central moving question. So in the debate before the U.S. entry into World War II, which came belatedly as far as Niebuhr was concerned, one of the issues he was raising in the late ’30s was, has no one any responsibility for the fact that the Nazis aim to annihilate the Jews? He understood that was part of the Nazi agenda. Everybody who paid any attention knew that. Are they not our brothers and sisters? if you will. So I think that kind of engagement with the world in and through caritas, Christian love, translates as a kind of responsibility, then you have to figure out what you can reasonably be responsible for.

MS. TIPPETT: Here’s something he wrote in Christianity and Crisis, which he wrote in 1952. But again, the context of this remark is that he was extremely politically active, that he wrote…

DR. ELSHTAIN: Indeed.

MS. TIPPETT: …he wrote, “Religion is more frequently a source of confusion than of light in the political realm. The tendency to equate our political with our Christian convictions causes politics to generate idolatry.”

DR. ELSHTAIN: He reminds us that politics, which is a good and which drew him, drew him to the point of exhaustion.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

DR. ELSHTAIN: If you read biographies of Niebuhr, he was just nonstop activist, if you will, on many, many fronts and, no doubt, foreshortened his life, at least many believe that it did. But he was insistent that politics is not an ultimate value, it is a relative value. It is one good among many. And if we assume a kind of ultimacy in our politics, then that is in fact an idolatry, assuming a kind of perfectionist standard that can never be achieved.

MS. TIPPETT: Bethke Elshtain is Laura Spelman Rockefeller Professor of Social and Political Ethics at the University of Chicago Divinity School.

And here is Reinhold Niebuhr preaching in 1952.

MR. NIEBUHR: (archival audio) Because when we say that we believe in God, we’re inclined to mean by that that we have found a way to the ultimate source and end of life that gives us, against all the chances and changes of life, some special security and some special favor. And if we don’t mean that, which is religion on a fairly adolescent and immature level, we at least mean that we have discovered amidst the vast confusions of life what we usually call the moral order according to which evil is punished and good rewarded. And we could hardly feel that life had any meaning if we could not be certain of that. Think of the words of the Psalms, “A thousand shall fall at thy side and 10,000 at thy right hand, but the evil shall not come nigh unto thee.”

One thinks of the intercessory prayers that many a mother with a boy in Korea must pray, “A thousand at thy side and 10,000 at thy right hand, let no evil come to my boy.” What a natural prayer that is and how finally impossible. The Christian faith believes that beyond, within and beyond, the tragedies and the contradictions of history we have laid hold upon a loving heart, and the proof of whose love, on the one hand, is the impartiality toward all of his children and, secondly, a mercy which transcends good and evil.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. And this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “Moral Man and Immoral Society: Rediscovering Reinhold Niebuhr.”

My final guest, Robin Lovin, is a theologian and ethicist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas and a leading, contemporary scholar and teacher of Reinhold Niebuhr’s thought. When Lovin began his graduate studies in 1974, Niebuhr still towered as a giant figure of the previous generation. Like all my guests, Lovin concedes that Niebuhr’s singular stature was possible in part because of the relative homogeneity of American culture at mid-century. But Lovin finds Niebuhr’s essential approach instructive even in a more fragmented and pluralistic world. Niebuhr was concerned in his time with the great global confrontation between religious and secular worldviews. Lovin suspects that Niebuhr would be fascinated by today’s new national and global discussions of the role of religion in society, politics, and democracy. I asked Robin Lovin how Reinhold Niebuhr might begin to think about that.

DR. ROBIN LOVIN: Niebuhr always approached issues by trying to say two things that are in tension with each other, and maybe it’s in that tension that his creativity comes. Because the first thing that he would do is tell us to be realistic, not to begin with some ideal model of how church and state are related. And though we can learn a lot from history, not to go back to Jefferson and Madison as if they had it all worked out, but pay attention to what’s actually happening in the world around us. The other thing that he always held up is the mutability, the changeability of all historical forms.

I think that what his theology gave him primarily was a point of permanence outside the flocks of history so that he didn’t have to rely on any of the historical circumstances of his time. So his creativity was in this ability both to be realistic about what was going on and at the same time to tell us never to absolutize the historical situation in which we live, to realize that its parameters are always open to change. And we’re going to be most surprised by the way those basic historical realities change, not just by, by events that sneak up on us.

MS. TIPPETT: Is there something that’s happening in our public life, an idea that’s out there where you are finding the thought of Niebuhr to be especially informative for you as you approach it?

DR. LOVIN: Well, his way of understanding the forces at work in international relations are, that’s a very important part of his legacy right now. And every time we start talking as if liberal democracy and market economies were going to be the human future for all time to come, every time we start thinking that way, we really ought to hear Niebuhrian alarm bells going off in all of our heads to remind us that the institutions of history are always changeable and none of our accomplishments are ever as final as we would like them to be. The underlying temptation to conceive of one’s own interest as too central to history, that’s the perennial fact about human life. And what you’re always trying to do as a realist is to figure out how is that working itself out in the current historical situation?

MS. TIPPETT: There is this quality of humility that I keep hearing about as I look into this figure of Reinhold Niebuhr that was apparently there in his person, in his personality, and there’s something like humility in the stance, in the attitude you just described towards one’s own position in the world. But especially for people who haven’t read him, I mean, there was an incredible prophetic, strident, aggressive, strong voice. And there was a realism about power and also a willingness to take power seriously and to exercise power in a way, right?

DR. LOVIN: I think that’s right. I really think that Niebuhr, for all the power that he had as a speaker and his ability to move people, and you talk to people now even who were his students 30 and 40 years ago, and they, they still have this memory of his powerful preaching and his ability to hold a class and, even in conversation, to kind of dominate a room. And yet I really think Niebuhr himself thought of himself as a servant of those ideas that he was trying to share. He didn’t get the hearing that he got from political figures and from academics all across the country and so forth by being a bombastic figure. I think he really did have an ability to go into a room and hear what people were genuinely concerned about and then articulate those fears and concerns back to them in a way that it made sense. It was because he really was a listener at heart that he was able to speak so clearly out of what was actually going on in the political world around him.

MS. TIPPETT: And you also, I believe, have a special interest in issues of racial morality, racial justice, right?

DR. LOVIN: Yeah, yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: So I would say at this particular moment in our history, not that that maybe shouldn’t be at the top of our list, but there are other moral and social issues that are more prominent in our public debate. But, you know, then again, the question is not so much where would Niebuhr come down on, I don’t know, on gay marriage, what would his position be, but how might he think this through. And it seems to me there’s something interesting in his thought, instructive in terms of his ideas about how social change and moral change, in fact, comes about.

DR. LOVIN: Right, right. Niebuhr always talked about how in American life our practice is better than our theory, and sometimes that was true for him as well, I think. In the early stages of the civil rights movement, Niebuhr was very hesitant about the kind of mass action that Martin Luther King was bringing about because he was worried about backlash and resistance, and he thought it might slow down the process of change. Now, it’s interesting, of course, that King in “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” you know, gives Niebuhr’s Moral Man and Immoral Society the credit for giving him the idea of nonviolent resistance. But nonetheless, that was Niebuhr in the 1930s. Niebuhr by the 1960s was a little more hesitant. There again, I think that’s where we have to be wise enough to correct his theory by paying attention to practice.

I think what we’ve learned from the 1960s onward is the power of groups of people to produce change. I don’t think that he could conceive of a world in which the apartheid regime in South Africa and the communist regime in East Germany, and so forth could, could really be overthrown by these kinds of mass movements. I’d like to think, however, that his basic understanding of the vulnerability of all institutions and structures in history would have made him receptive to those kinds of changes and willing to learn from those new kinds of strategies.

MS. TIPPETT: Robin Lovin. Here is a South African voice from the Speaking of Faith archives, the theologian Charles Villa-Vicencio. He used Niebuhr’s ideas as he worked with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission after the transformation of his country in the 1990s.

MR. CHARLES VILLA-VICENCIO: I cut my theological teeth about 100 years ago on Reinhold Niebuhr, Moral Man and Immoral Society, that it’s easier to be a moral individual than a moral community. All sorts of forces are built into those communities, which make it very, very difficult to persuade communities. And as a government commission, we could not reconcile the nation. We couldn’t offer forgiveness. All we could do was to try and create a space within which people listened to one another, damn it, and to the extent that a greater depth of understanding, of being aware of what drove people to do these dreadful things, as that understanding began to emerge so the morality began to flow in.

MS. TIPPETT: You quote Niebuhr as saying, “Justice will require that some people contend against us.” In other words, he might not, also not have been surprised by the contentious atmosphere in our society today. I mean, talk to me about that conviction of his and how he lived with that.

DR. LOVIN: That quotation comes, in fact, from one of the first articles he wrote back in the 1930s, when he started talking about Christian realism as a name for this attitude that he brought to politics. And again, I think this is what makes him a figure who is at home in our way of thinking about the world now. He wasn’t alarmed by controversy and conflict because he didn’t think that the goal was to find one group whose ideas so matched truth and wisdom that we could give them the power. The whole point was that even the wisest among us benefit from criticism and from the people who think that we’re totally wrong-headed in the way that we look at the world.

MS. TIPPETT: And it’s interesting that Niebuhr, I find, does get used on both sides of all kinds of specific debates.

DR. LOVIN: Yeah, that — that’s exactly right.

MS. TIPPETT: So what does that say about him and his ideas and his legacy?

DR. LOVIN: We seem to have the notion that controversy and conflict and polarization in the society ought to go away, that we will someday return to something that’s normal, you know, in which there won’t be this kind of polarization. Whereas I think Niebuhr would say, look, normal is what we’ve got now. What I think Niebuhr opens us up to is being more hopeful and less anxious about this conflicted time in which we find ourselves.

MS. TIPPETT: And yet staying very engaged.

DR. LOVIN: Staying very engaged and not assuming that the boundaries that are drawn now are the boundaries that are going to last forever.

MS. TIPPETT: Robin Lovin is the Cary M. Maguire University Professor of Ethics at the Perkins School of Theology of Southern Methodist University. In closing, here is one of the most beloved and often-quoted passages of Reinhold Niebuhr’s writing from his book The Irony of American History. He wrote, “Nothing that is worth doing can be achieved in our lifetime; therefore, we must be saved by hope. Nothing which is true or beautiful or good makes complete sense in any immediate context of history; therefore, we must be saved by faith. Nothing we do, however virtuous, could be accomplished alone; therefore, we must be saved by love. No virtuous act is quite as virtuous from the standpoint of our friend or foe as it is from our own standpoint; therefore, we must be saved by the final form of love, which is forgiveness.”

Reinhold Niebuhr displayed a lighter, more personal side in his correspondence with figures like the Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter, the poet W.H. Auden and Vice President Hubert Humphrey. An interactive timeline at speakingoffaith.org features actual photos of these letters from Niebuhr’s personal archives at the Library of Congress. We also are providing my complete, unedited interviews with my guests in this show and others, including Reinhold Niebuhr’s daughter, Elisabeth Sifton. Download them on our Web site or the SOF podcast, and learn more about Reinhold Niebuhr’s influence on his time and ours. All these and more at speakingoffaith.org.

The senior producer of Speaking of Faith is Mitch Hanley, with producers Colleen Scheck and Shiraz Janjua. Our online editor is Trent Gilliss. Bill Buzenberg is our consulting editor. Kate Moos is the managing producer of Speaking of Faith. And I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.