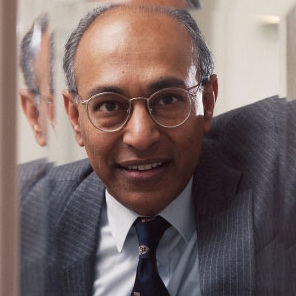

Prabhu Guptara

The Gods of Business

In an age of Enron and WorldCom, how can we imagine a place for business ethics, much less religious virtue, in the global economy? We speak with a Hindu international business analyst who offers learned, fascinating observations about how the world’s myriad religions have shaped global business norms and practices.

Image by Samson Creative/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Guest

Prabhu Guptara is Director of Executive and Organizational Development at the Wolfsberg Centre, a subsidiary of UBS of Switzerland. He writes and lectures about issues at the intersection of business practices, religious worldviews, and ethics.

Transcript

February 23, 2006

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, a conversation about global business ethics and what my guest, Prabhu Guptara, calls “the gods of business.” He reflects on such ideas for one of the world’s largest Swiss banks.

MR. PRABHU GUPTARA: A generation of people has grown up — particularly those who occupy high positions in politics, economics, the media and all the rest of it — who have no transcendent values, or, if they have transcendent values, they have no means of intellectually reconciling those transcendent values with the way they do business.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. My guest this hour, global business analyst Prabhu Guptara, has fascinating perspective on how an Enron scandal can happen and why it matters to people around the world. He explains how the United States can be one of the world’s most religious countries, yet, at the same time, a culture in which moral values can fail to penetrate the workplace.

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics and ideas. Today, “The Gods of Business.”

[Announcements]

REPORTER WADE GOODWYN [FROM NPR’S “ALL THINGS CONSIDERED,” JANUARY 31, 2006]: In Houston today, federal prosecutors presented their opening statement in the case that the judge calls “one of the most interesting and important cases ever tried.” It has been four years since the Enron Corporation collapsed in an accounting scandal that still reverberates on Wall Street and in corporate boardrooms.

REPORTER MELISSA BLOCK [FROM NPR’S “ALL THINGS CONSIDERED,” JULY 7, 2004]: Including that their advisers, their accountants and their lawyers told them it was OK to do what they did, they also may say that what they’re being charged with wasn’t actually illegal, it was just business.

MS. LOIS BLACK [FROM NPR’S “ALL THINGS CONSIDERED,” JANUARY 30, 2006]: I am in my 60s and should be retired at this point, but I will have to continue to work because I lost about 75 percent of my retirement in Enron stock.

MR. ROBERT MINTZ [FROM NPR’S “MORNING EDITION,” JANUARY 30, 2006]: …going to be to present this as a clear-cut case of criminality. They’re going to show the jury that on the one hand, the defendants were aware that Enron was in serious financial trouble, and, at the very same time, they were turning around and telling the investing public something entirely different.

MS. TIPPETT: Prabhu Guptara reflects on such headlines and scandals for one of the world’s richest and most influential banks, the Union Bank of Switzerland, better known as UBS. Every central bank in the world with more than $1 billion in assets is a client of UBS, where Guptara creates and directs executive and organizational development programs. He also writes and lectures widely on globalization, financial services, business ethics and religious values. He’s long pursued a curiosity about how religious traditions function as worldviews and how these traditions interact with the way human beings conduct business. I asked Prabhu Guptara how he first came to this.

MR. GUPTARA: I guess I started thinking about it when I was about 16. And the reason was that I was really facing the issue: How is it that a highly religious country like India is also at the same time so highly corrupt? And why is it that when people claim that we’ve had a massively beautiful, wonderful history in the past, which obviously we did, we are in such a mess at the present? And is there any relationship between the philosophies we followed in the past and the philosophies we are following at present? Everybody claims there is, but if there is, then clearly the philosophy had nothing to do with our success in the past and our failure at the moment. So where does all this fit together? And, of course, since I work for a business now and I worked for a bit of a business then, I was asking the question how does the fact that somebody’s highly spiritual relate or not relate to their business practices?

MS. TIPPETT: As he considers such questions, Prabhu Guptara looks at different teachings and emphases across the world’s traditions. For example, he says, Buddhism, Confucianism and Hinduism emphasize social order. Where business is concerned, they offer their followers commonsense advice more than spiritual principles. Judaism stresses the character of God as a model for life and work. Islam stresses the will of God. Christianity promotes human transformation, even transformation of the workplace.

But Prabhu Guptara has observed that business is rarely defined by the particularities of the faith of executives and employees. He’s seen a more ecumenical and transnational human tendency to separate one’s private values from one’s approach to work. “It is possible,” he says, “to be religious but not ethical when it comes to economics.” He knew this first in his own Hindu upbringing.

MR. GUPTARA: I come from a caste that has been business people for 2,300 years at least. And we are allowed by our religion, we are, in fact, encouraged by our religion, to charge whatever level of interest we want. And so, over the years, we have charged as much as 3,600 percent interest because the market will bear it. And we have reduced tens of thousands of people — tens of millions of people to slavery, virtual slavery, serfdom, over the years because they were not able to pay back the interest on loans that we gave them. So, clearly, it was possible to be highly religious in business, as most members of my caste are, but at the same time highly unethical, or at least highly unhuman or inhuman. So, “How do all these things fit together?” were questions that were bothering me, and that’s really why I started exploring them.

In the world today, you can think of most people in the world falling into, I guess, two or three different categories. One, people who don’t see that their values — wherever their values may come from — have anything specific to do with their business practice. They’re just trying to follow good professional ethics. And I guess most people in the world fall into that category. They don’t really think about where those business ethics have come from or professional ethics have come from.

MS. TIPPETT: And that would be most people, regardless of how devout their religious tradition might be or their different religious traditions.

MR. GUPTARA: That’s my experience. I mean, it doesn’t really matter if they’re Muslims or Hindus or Buddhists or Christians or atheists or what. You know, if they run a business, they try to run a business that’s decent, legal, honest, truthful and all the rest of it. You know, they just want to make a decent sum of money in a decent way, most people. Of course, there are a few people who are highly greedy and who will do whatever it takes, including cutting corners and being unethical and all that, in order to make money. They will do whatever they can get away with in order to make a lot of money very quickly. And it doesn’t matter what their theoretical religious background is…

MS. TIPPETT: They might also be very religious.

MR. GUPTARA: They might also be very religious, yes.

And then you’ll find an equally small minority — by equally small, I mean as small as those who are very highly greedy and so on — you’ll find an equally small minority that wrestles with questions of “Is this the right way to make money? Am I making too much money? What is the effect of my business on my clients? What is the effect of my business on my suppliers? What is the effect of my business on the environment? How do I square the amount of money I’m making with my responsibilities in a world of extreme need?” And, again, in my experience, it doesn’t matter what the religious background of the people is, there is a small minority of people that is concerned about that kind of issue.

MS. TIPPETT: You have a very large presentation that you make in which you lay out the different approaches to business in the five predominant, largest religious traditions, in which you group Christianity, Islam and Judaism together, and then you also talk about Confucianism, Hinduism, Buddhism and atheism. A place I believe you come out is that those religious traditions and those worldviews make themselves felt in many ways, but that, in fact, the god of business that is most prominent — the culture of business — has become atheist. Is that too extreme?

MR. GUPTARA: I would say that is too extreme. If you look at the ethics of most businesses and if you look in most professional ethics and you say, “Which religious tradition do these square with most?” you will see that they square really with the Jewish and Christian traditions — marginally with the Muslim tradition because Muslim tradition belongs to the same Abrahamic family of faiths — and doesn’t really square with Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, African tribal religion and so on and so forth.

MS. TIPPETT: And is that true of business even in China or in India?

MR. GUPTARA: Yes, because you find that the most, within quotes, “developed” or “sophisticated” business practice goes in the direction of what we might describe as international business practice — international best business practice. And international best business practice comes out of the Jewish and Christian tradition.

I mean, take a simple thing like no bargaining. In most, you know, the more established the market becomes — and it doesn’t matter which part of the world you’re in — the less haggling and negotiation is a mark of that market. This tradition was really started by Jewish and Christian people who believe in the value of time and said, “Time is so important that the amount of time that’s wasted in negotiation can be — and in haggling in marketplaces — can be reduced if we just go for a fair price that is fixed. And provided I’m making a decent return, I don’t have to start at 300 percent of what I’m expecting to get or 1,000 percent of what I’m expecting to get. I can just start with what I expect to get.” And that has become established over time as being international business practice. But where it comes from is the value of time vs. the value of money. If time is the most important thing in life, then you shouldn’t waste it haggling.

MS. TIPPETT: So you’re saying that there are very real ways and very practical ways in which a Jewish/Christian ethic has infused international business practices. But is that the same as creating ethical cultures within workplaces and corporate cultures?

MR. GUPTARA: That is a rather more difficult or different issue. And it’s equally possible for somebody from an atheistic point of view or from a Buddhist point of view or a Muslim point of view or an African tribal point of view to create an ethical culture as it is from somebody from a Jewish or Christian point of view. And, in fact, it’s not necessarily the case that somebody who is Jewish or Christian and owns a business is necessarily going to create an ethical culture.

For example, in China and in Japan, in one case, it was Marxism — in the case of China — it was Marxism that cleaned up the country and made it relatively straight till, of course, now, market practices have come in and the country’s gone back to a kind of corruption.

In the case of Japan, it was national sentiment, you know, the desire at the end of the Second World War to catch up with the West. So it was a kind of nationalistic religion, nationalistic fervor which cleaned up business to a very large extent, of course, not completely.

African nationalism cleaned up a lot of business practices. And, of course, now they’ve slipped back again, because the issue is not just whether you can create this kind of national or corporate drive to create a culture which is ethical. You can do it within one generation — that’s not easy, but it’s relatively easy — but whether you can sustain that over two or three generations, that is a challenge.

MS. TIPPETT: Global business analyst Prabhu Guptara.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. We’re talking about what Prabhu Guptara calls “the gods of business.” He works at one of the world’s most influential banks. From that vantage point, he’s become increasingly concerned about inequities that the global economy can fuel. In recent months, natural calamities across the world have brought some of these into high relief and underscored their human cost; so, in a positive way, have the efforts of high-profile philanthropists and humanitarians, notably Microsoft’s Bill and Melinda Gates. Prabhu Guptara believes that the future viability of even the most successful enterprises will require that they address excessive inequalities. Here’s a reading from an address he published and delivered in London called Ethics Across Cultures.

READER: I have no issue with people earning lots of money. I do have a problem when, for example, in the richest country in the world, the U.S.A., we have a population in which 70 percent has no net wealth. Over the past 20 years, real wages have declined for 80 percent of the population. And this is not an issue only in the U.S.A., it is a worldwide trend today. I think most of us have no problem with a system which allows reasonable accumulation of wealth gained in return for the exertion of intelligence, industry, risk-taking and sheer effort. But I think most people in the world do have a problem with a system which allows unlimited accumulation of wealth at the same time as allowing millions of people to have nothing when they are exerting as much energy and intelligence as other people. Three thousand five hundred children died today because they had no food or water. Three thousand five hundred will die tomorrow for the same reasons, and the day after and every day — until you and I decide to do something about it. What was merely a tragedy yesterday is today a tragedy as well as an obscenity, for we live in a time of oversupply of all basic goods for the first time in history, which makes it entirely unnecessary for anyone to starve or have no clothes or to have no roof of some basic sort over their heads.

MS. TIPPETT: From an address in London by Prabhu Guptara. For all his concern about the human costs of the global economy, Prabhu Guptara doesn’t concentrate blame on the nature of business itself. The global economy, he says, simply magnifies the fact that, as they grow, businesses affect the world around them.

MR. GUPTARA: That means to say, if you have a factory, the factory is going to produce certain pollutants. As you deal in business, you may be driving competitors out of business. And the question, as we are today in a globalized economy, is how can we organize the whole of the global economy in a way that makes sense for the maximum number of people in the world? I think the U.S. secretary for labor went on record in 1999 saying that the majority of the benefits of the boom — the greatest boom the world had ever seen for the 10 years or so between 1989 and 1999 — the vast majority of the benefit of that boom went to 1 percent of the U.S. population. Now, there’s nothing wrong with a lot of benefit going to a very small number of people, but till recently, you see, we were forced to make a choice because we had limited resources. And by “till recently,” I mean till 50 years ago. Even at the end of the Second World War, we lived in a world in which we were constrained by resource shortage. And everybody remembers at the end of the Second World War — certainly when I’m sitting here in Europe or in Switzerland — that there were long lines of people waiting who had pieces of card in their hand on the basis of which they could go to the shop and get their quarter-kilo of sugar or their loaf of bread or their two ounces of meat per week.

Now, of course, we live in a world of such enormous abundance that people are paid not to produce. My brother is a farmer in Austria and his farm produces absolutely nothing. And the reason his farm produces nothing is not because he’s a stupid black man but because the government pays him to produce nothing. And all over Europe, we have butter mountains and beef mountains and wine lakes and milk lakes and cheese mountains that are preserved and maintained, kept away from the market so that we can maintain market prices at the same time as we are paying for the preservation of these goods, agricultural goods. And the whole thing is a complete mess when you look at it globally. This is not any sensible way to run the world.

MS. TIPPETT: And it’s an ethical mess, as well, which…

MR. GUPTARA: It’s an ethical mess as well as practical mess. You know, on the one hand, people are starving; on the other hand, we’re keeping goods out of the market because you want to maintain prices.

MS. TIPPETT: And the effect of listening to that litany of madness, as you describe it which, you know, those are statistics that bombard us in newspaper accounts and documentaries. And the effect on me, and I think the effect on many people, is simply to throw up my hands and say, “These problems are so large, the structures are so complex, how can that ever possibly change?”

MR. GUPTARA: You know, people are discussing what we can do about the monetary system because the monetary system that we have at the moment is purely a fiat by decree.

MS. TIPPETT: And what does that have to do with these huge inequities that you talked about and this gap between supply and demand — people starving on the one hand and huge stockpiles on the other?

MR. GUPTARA: What it has to do is the following: As long as we have a money system that is based on fiat — that means simply a government’s say-so, a government can just create any amount of money that it wants to at any given moment without anything necessarily backing that promise — then we can create a system in which there are global booms and busts which are outside our control.

This is too complicated to explain very simply. But let’s say there is demand for computers today. And if there is a market demand for computers, every single computer manufacturer gears up to produce more and more computers. But at some time, for whatever reason, the demand in computers slacks off, for whatever reason. Then suddenly there’s a glut in the market of computers that are being produced by all these different manufacturers. Now, why do computer manufacturers set up all these factories? How are they able to set up all these factories? Well, they’re able to set up all these factories because they can borrow money on the basis of what they perceive to be and what they can present to their bankers as being more or less guaranteed demand. And, of course, if the money’s lent to them, the factories can be set up and, of course, this business goes on.

So because of having a currency that is based on fiat, we are much more able to generate production at a rate that is uncontrolled. And markets control things then by going into a bust when there is too much supply in the market. Am I making sense?

MS. TIPPETT: Yes, you are. So, you know, I’m very interested if you can, tell me how change could happen, where change could happen. I mean, what do you see? Are other people like you, in positions like you, asking these questions? Are people pursuing these questions?

MR. GUPTARA: Oh, yes, indeed. These kinds of questions are big questions, and people are discussing them and debating them. And we can inform ourselves about the debate; that’s one thing we can do. And, secondly, having informed ourselves about these kinds of issues, we can begin to ask our representatives in parliament or in Senate or in the House of Representatives where they stand and how they see these issues. The third thing is to do what you can. Now, you and I cannot do anything about the world financial system or the world monetary system, but what we can do is take action in our locality and with our people.

And one of the great things about the United States is that wherever I travel I see small groups of people who are committed to doing things to make a difference, whether it’s students in school — I’m talking of, you know, really children in school — or whether it’s retired people, seniors, or whether it’s people who are working in companies in mid-level or top-level jobs, doesn’t really matter. But find something that you are passionate about which is going to make a difference in the world and put your shoulder behind it, because there’re so many issues that one can put one’s shoulder behind, whether it’s conservation-related issues to look after the environment, whether it’s poverty in our own communities. I mean, the United States has 12 million people who are poor, which is about a tenth of the U.S. population in very round figures. So there’s a lot to do just in the States in terms of eliminating poverty, let alone eliminating poverty and helping poor people in other parts of the world.

And then there are political actions you can take to support things that can help. I mean, for example, what’s happening in Sudan at the moment is something that was known about for ages, but the U.S. government, for example, did not take a strong line on what was happening in Sudan till groups of people in the U.S. started taking Sudan seriously, started lobbying the government and saying, “Hey, you’ve got to pay attention to this issue.” And if each of us do our part, as many people are doing their part, more than we think, then the world can be cleaned up.

I mean, I think of Transparency International, which is helping to clean up the business of corruption worldwide — one man’s vision. One man working for a multinational in Africa got fed up of seeing the extent of corruption around him, determined that he would help to clean up corruption worldwide. And Transparency International has now got to the level of nearly — I don’t know exactly what the situation is today — but we’re at the point of outlawing corruption in business worldwide all because of one man’s work over, I don’t know, 20 years, 15 years, something like that.

MS. TIPPETT: Prabhu Guptara of the Union Bank of Switzerland, UBS.

Until fairly recently, corruption was a widely tolerated norm in economies across the world. Even Western businesses, which would not condone open corruption in their own cultures, have, at times, integrated practices such as bribery into their dealings with developing economies. In doing so, they have sustained and fueled such practices. Transparency International, which Prabhu Guptara mentioned, was founded in 1993 and now has chapters in over 80 countries. This organization doesn’t expose individual cases of corruption; it works instead at the national and international levels to curb both the supply and the demand of corruption.

This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, more of Prabhu Guptara on differences in attitudes towards business in religiously active America and religiously agnostic Europe. Also, how Enron and other U.S. corporate scandals might be affecting global practices.

This exploration continues at speakingoffaith.org. This week you’ll find Prabhu Guptara’s PowerPoint on the gods of business. Use the Particulars section as a guide and download this show to your desktop or subscribe to our free weekly podcast and listen on demand at any time and any place. While exploring, read my journal on this week’s topic and sign up for our free e-mail newsletter. All this and more at speakingoffaith.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “The Gods of Business.”

As former Enron executives come to trial in Houston, I’m speaking with Prabhu Guptara. He directs executive and organizational development programs for UBS of Switzerland, one of the world’s largest banks. He also travels and lectures around the world about issues at the intersection of business, religion and ethics. We’ve been talking about how religious traditions influence corporate morality from the office to macroeconomics. Guptara insists that as the global economy grows there is a compelling need for individuals to assert personal ethics and moral values in the world of business. Europeans observe with fascination and some puzzlement that the United States is the most religiously active society in the developed world.

MR. GUPTARA: The US has the highest number of people who go to church on the face of the Earth. About 70 percent of people say they believe in God, 40 percent go to church every Sunday. Now, this is, you know, quite extraordinary, because in Europe — in Switzerland, where I sit — and in Europe, 1 percent of the population goes to church every Sunday.

MS. TIPPETT: Although I’m interested in this way in which you describe that it’s not necessarily a straight line between being religious and being ethical in business. And one thing you point out is that, for example, whereas business is regulated by law and business ethics also are regulated by law in the United States, let’s say in Europe it’s more in terms of principles. And I wonder if, even though, as you say, only 1 percent of Europeans go to church, whether having a sense of principles might lead in general to more ethical practices.

MR. GUPTARA: Sure, but it depends on what the principles are. I mean, Hitler had principles. Mao had principles. Osama bin Laden has principles. And this, of course, is extremely politically incorrect in the States at the moment to start discussing what principles people have and whether they’re OK principles or not OK principles. Nevertheless, that is the debate that we need to have. You know, what are civilized principles, say, human principles and what are noncivilized or nonhuman principles that, you know, we will not accept in a global system?

MS. TIPPETT: Let me ask a question this way. As you travel and do business and observe business all over the world, what are some of the guidelines or tests you would apply? What principles work for the good of people and of society?

MR. GUPTARA: On the one hand, there are societies where the individual matters not a bit. China, Japan — traditionally, I’m saying, traditionally — India, the Middle East, Africa or pre-Reformation Europe are all examples of societies where the individual didn’t count. Society counted, the community counted, but the individual didn’t count. So in those kinds of oppressive societies, the issue is how do we open those societies up so that individuals can be individuals?

In the West, of course, and in Europe, you’ve got the opposite problem at the moment. You’ve got so much individualism that it becomes destructive of society. And so the issue is, how can you encourage individuals to take individual decisions, but at the same time to take individual decisions that enable them to take responsibility for society and not destroy society?

The other criterion is does it improve the life of — I mean at the material level — does it improve the life for most individuals on the Earth or does it improve the material well-being of only a few people on the Earth?

And the third is, as we improve the level of material well-being of individuals on the Earth, are we doing it in such a way that we are storing up huge problems for the future? So my key word would be “responsibility.”

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder if you have any stories you could tell me of particular businesses or cultures or localities where people are really working to achieve that kind of balance that you described?

MR. GUPTARA: Yeah. I’ll give you a very small example. I work, as I said, for one of the world’s largest banks or, as you said, for one of the world’s largest banks, which is true. And if you go back 20 years, we had a reputation here in Switzerland for being the center for the world’s dirty money. And I’m sure in some parts of the world we still have that reputation. But 15 or 20 years ago Switzerland began to really clamp down and make a determined effort to keep dirty money out of Switzerland. Now, though that started a long time ago and has made an impact gradually and slowly over the whole of the industry, the public perception didn’t seem to have changed a lot. And so one of my colleagues took his reputation in his hands, went to our chief executive and said, “We need to be doing something about this so that we can actually change not just our own practices, which we’ve been doing gradually over the last 15, 20 years, but change practices in the entire industry. I mean, if we don’t take dirty money but somebody else is taking dirty money, well, that’s all very well for us but it doesn’t sort the situation out globally. And it’s very bad for us because it means competitively we’re losing out because our competitors are getting the dirty money and we’re not getting the dirty money. That doesn’t do us any good in the marketplace because they’re being more successful than we are.”

And so we brought together 12 of the world’s largest banks — private banks, wealth managers — and put in place industry standards that the 12 largest banks were willing to stand by. And this group, which is called the Wolfsberg Group, put in place the anti-money laundering principles that were already practiced in most of these banks — perhaps in all these banks, I don’t know — but articulated them for the first time and made them an industry standard. And today, I don’t know, about 100 banks are very keen to adopt these anti-money laundering principles, and more banks will, no doubt, follow.

Now I come to September the 11th. When September the 11th happened and the U.S. government asked all the major banks in the world to provide facts and figures about, you know, where money might have been coming in to support terrorism from, there were very few banks worldwide that were able to produce the facts and figures very quickly, and our bank was one of them. And the reason we were able to do that was because of my colleague’s work in the whole anti-money laundering area.

So individuals can make a difference, individuals do make a difference, and individuals can make a much bigger impact than they think of and they dream of if they’re willing to take their responsibility seriously.

I think of this dear lady, whom I’ve never met, whom I don’t know, who exposed the whole of the Enron scandal. It was one woman. So individuals have enormous power. And we are fed consistently, somehow, by our culture the devil’s lie that we have no power and it’s only poor old me. Yes, it is only poor old me. But poor old me, poor old I have enormous power if I’m willing to keep my eyes open and keep my ears open and act at the right time when it’s necessary to act to clean things up or to improve things. Things may be perfectly clean, but they could be improved a bit. So individuals with vision, that’s what we lack.

MS. TIPPETT: Business analyst and educator Prabhu Guptara. He is Indian-born and a practicing Hindu. He works in Switzerland and consults in the United States and the rest of the world. Corporate scandals have engendered cynicism about business ethics in many Americans. I asked Prabhu Guptara how he interprets the discrepancy between America’s religious and moral ideals and high-profile corruption.

MR. GUPTARA: I can’t see how you are going to create a culture in which ethical and moral standards are going to be maintained. You are still living on the basis of inherited moral capital that came down to you from the great figures of U.S. history who transformed America from being a frontier civilization to being a settled civilization. Now, America’s going through this so-called culture war between people who are committed to some transcendent value — you can call it Christian, Jewish, Muslim, doesn’t matter what it is — but who are committed to some kind of transcendent value on the one hand and on the other hand people who are not.

MS. TIPPETT: But are you saying that there is a moral foundation in other cultures that in America has been lost?

MR. GUPTARA: You see, Europe is an old society. Europe is a settled society in the same way that India is a settled society or China is a settled society. And what happens is, if you don’t have religion, which many people here do not, as we’ve discussed, you still have society. You still have very close family.

Well, in the little village in which I live, population 10,000, most people were born in that village, have lived in that village and will die in that village. Most people went to school with a group of people who are still their friends. Most people are still living in houses not very far away from their grandparents. So grandparents, parents and children are within walking distance of each other. And even when people go as far as Australia or the States — of course, some people immigrate. That’s different. But if they come back, they won’t come back and settle down, let’s say, three hours’ drive from their grandparents, they’ll come and settle down usually within a 20-minute drive at the most of their parents or their grandparents. So it’s a very settled society, and this settled society means that traditional ethics are still extremely important. People know each other very well, and, as a result of knowing each other very well in a settled society, you can cheat somebody once but you won’t be able to cheat somebody twice or thrice, unlike the U.S., which is a highly mobile society where people can be individually religious, but they have no social bonds around them to keep them, you know, within moral limits. So if their individual ethics keeps them within moral limits, fine. But if the individual ethics does not keep them within moral limits, there’s nothing else to keep them within the moral limits.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. So you’re saying that in the United States, in fact, it is more critical that, you said, that there are some kinds of transcendent values that individuals, in fact, hold?

MR. GUPTARA: Right. Right.

MS. TIPPETT: OK, interesting. Well, you were getting ready to talk to me about, then, what the implications of this loss of transcendent values in the United States means. What does Enron really say about business today? Or is it really about business in America? Or is it really about American culture more than anything else?

MR. GUPTARA: I guess it’s a statement about all of those things at some level because business is ultimately about trust. It doesn’t matter how many rules you have, how many regulations you have and how many systems and processes you have. At the end of the day, you cannot go around policing each of your employees to make sure that they’re not defrauding you, they are not cheating, they’re not lying and all the rest of it. And I think the United States is very rapidly coming to a situation where you cannot naturally trust people any longer. Essentially — whatever you may say about Enron and Arthur Andersen and all the rest of it — essentially it was a result of the inability to police people at the top because people at the top were not policing themselves and there was nobody around to police them. Because traditionally, people have been policed from the inside by themselves and not by others in your society in the United States. And, as this business of people’s consciences begins to break down, people’s ability to understand and make ethical decisions breaks down, it becomes much more difficult to build world-class businesses.

MS. TIPPETT: Because that trust would also be lost on the part of other global business leaders vis-à-vis American companies?

MR. GUPTARA: You’re right. I mean, you see, America has become such a legalistic society now that there are businesses that are seriously thinking “Is it worth doing business in the United States?” And the reason is, when I do business with a colleague here in Europe, generally speaking we reach a gentlemen’s agreement and that’s that. If we need to bring in contracts and lawyers, OK, we bring in contracts and lawyers. And obviously at some point, somebody needs to sort the whole thing out legally and put it all down in black and white. But that’s not the basis on which the business is done. The business is done on the basis I look you in the eye and I say, “This is the deal. Right?” And the person says, “Right. I agree.” And you shake hands on it, and that’s the deal. That’s the way business is done.

Now, in the U.S., you know all about the army of lawyers that’s needed before you can do any deal at all. And, of course, as American business practices have been exported around the world, more and more legalistic systems have come in. And that has its positive side, of course, when you get into large, complex deals because you need to know exactly what you’re contracting to do or not do, or pay or not pay, and when, to what quality, and all the rest of it. But there is really a sort of overkill at the moment on the legalistic system’s procedures end without looking at, hey, are we going to be able to sustain businesses if we carry on down this path? Or do we need to revisit the issue of how do we build trust, how do we build character in individuals? How do we create business cultures that are ethical? And if you don’t revisit those internal realities that are really what produced the greatness of the West as against the East, then the West is going to go down. And if you’re going to have essentially an unethical society in which you cannot trust people, not even your own employees and not even your own bosses, to do the right thing, then you will not be able to continue to be a prosperous society. I mean, it’s just as simple as that.

MS. TIPPETT:Prabhu Guptara of the Swiss banking concern UBS.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “The Gods of Business.”

Prabhu Guptara has told me how best practices in business worldwide were largely formed by practical values drawn from Judaism and Christianity. And in recent history, he says, these values were most powerfully embodied in American corporations. I asked him if, with scandals like Enron, that is seen to be changing.

MS. TIPPETT: I think Americans have a sense of our economy being so huge and our business leading the world that it’s hard to imagine that, rather than America being shut out of international business, whatever the problems are, that the American ethical cultures would, in fact, infuse the rest of the world’s business.

MR. GUPTARA: That’s certainly been the case till today that — you know, even till today this is the case. And it’s only begun to be reversed from about Enron onwards that people are saying, “Hey, if America’s like this, you know, do we really want American business practices?” And that’s still a marginal issue; it’s not a big issue. But, you know, it could become big if things continue along that path, and hopefully they won’t continue along that path. But that is a danger.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, tell me about those conversations. Are there practical things you can point to that changed with Enron in terms of the attitude and behavior of businesses in other countries towards American business?

MR. GUPTARA: Well, if you look back to about 20 years ago or 25 years ago, America was the first country to bring in the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. And the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act essentially tried — OK, not totally effectively — but it tried to outlaw the practice of bribery, and it was the first country to bring that in. Europe and the rest of the world only began to move as a result of the repeated hammering of organizations like Transparency International, which I’ve referred to earlier. So America was seen as some kind of moral exemplar, as some kind of moral leader in business. And, essentially, European businesses and other businesses didn’t like the American approach but had to conform to the American approach if they wanted to do business in America. So the issue was America was perceived as being a moral leader in a way that a lot of world businesses didn’t like, but because America was such a dominant power in business and was trying to be ethical, at least more ethical than the rest of the world, it was perceived as being moral. Now what happened is that this so-called moralistic business system coming out of the U.S. is suddenly perceived to be hollow as a result of Enron and Arthur Andersen and all the rest of it going down. And people start saying, “Well, you know, we are not as hypocritical as the Americans are because at least we don’t pretend to be moral. The Americans pretend to be moral, and then look what they’re like, really.” So what happened was that a whole thrust in terms of cleaning up world business lost steam as a result of Enron, on the one hand, and legalistic methods to try to make sure that people were ticking boxes and keeping to those rules have begun to come in instead.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, when people talk about business ethics in the United States, we’re generally talking about workplace cultures, employee ethics.

MR. GUPTARA: Sure.

MS. TIPPETT: And this is putting the whole issue on a much larger ground. We haven’t been talking about religion at all. In fact, it’s been mentioned that very religious people can be very corrupt in business, and people who are atheists can be very moral in business. You know, what does religion have to do with business ethics at this global level, if anything?

MR. GUPTARA: It is an issue because the question is where will we get a global business ethic from? Historically, as I said, the ethical practices in business have come out of Judaism and Christianity. That doesn’t mean they necessarily need to come out only from that. They could come out from Islam, they could come out from Buddhism, they could come out from…

MS. TIPPETT: Well, and you’re Hindu. I mean, yeah.

MR. GUPTARA: I’m a Hindu, sure.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. GUPTARA: The question is where are the people who will take on the challenge of creating that kind of a global business ethic and actually then implement it? And there are people who are trying to do that, but they are, at present, few and far between, and the initiatives are fragmentary and not as well-supported as they probably should be.

If you look at things like the Global Compact, which has been started by the United Nations secretary-general, Kofi Annan, and which now brings together some of the world’s largest businesses, they’re trying to take seriously this whole issue of what does it mean to be good citizen as a company of the world? And that is one kind of level at which you can operate. Another kind of level at which you can operate is training the next generation of leaders inside companies, not at some kind of global level, but inside companies. And a third level, obviously, is the level of the training that we give to our children in schools or in homes. And each of us, depending on whether we are parents or godfathers or godmothers or whatever of children, or by our actions in companies and in society, create this kind of global ethic or don’t.

And the question I think that I would like to leave us with in terms of religion and ethics is where does my religious or transcendent orientation, whatever that might be, where and how does that relate first to my individual ethics, to my group ethics in terms of the way my company operates, and then to global business ethics? And I think if more of us asked ourselves that question, we could begin to work out the answers quite satisfactorily. My problem is that most people don’t think about it and, when they begin to think about it, realize how ignorant they are of what their own religious tradition is supposed to be, whether it’s Christian or Muslim or Jewish or whatever it happens to be.

But if you look inside your own religious tradition, whatever that is, you’ll find whether that religious tradition is adequate in terms of helping you as an individual to live out ethical values individually and whether it’s adequate in terms of living out your ethical values inside your company or organization that you work for or in your community and whether it’s helping you to look at the big global issues like conservation and nature and poverty and all the rest of it.

The U.S. is the picture of the future, isn’t it? And if you look at Europe, Europe is being steadily Americanized. If we look at India, India is being steadily Americanized. If we look at China, China is being steadily Americanized. We are all going in the direction of greater individualism, greater fragmentation of society, greater mobility, greater individualism in a negative sense individualism, though, of course, individualism is also positive, as we discussed earlier. So throughout the world, we see this Americanization taking place. The elite throughout the world define themselves as being pro-American or anti-American, whether it’s in terms of business practice, politics, sport, Coca-Cola or whatever else. And this why the culture clash that is taking place, the culture war that is taking place in the U.S. is so significant for the globe, not just for the U.S. It will determine the direction in which the elite throughout the world move.

MS. TIPPETT: Prabhu Guptara is director of executive and organizational development at the Wolfsberg Center of UBS in Zurich, Switzerland. Prabhu Guptara names truths that are elemental yet rarely discussed. For example, that there is a transnational human tendency to set private ethics and religious values aside in the marketplace. In a highly mobile, individualistic society like the 21st-century United States, this creates corporate citizens with no binding sense of accountability. We’ve raised a generation of leaders who seem to require policing from the outside. This insight illuminates the human roots of an Enron scandal more incisively than many other complicated analyses.

Prabhu Guptara has a broad, global view, but his conclusions would challenge each of us. If we don’t want to sustain and export the ways of Enron, he says, we must all exercise conscience at work, whether we find it in religious or other kinds of ethical sources. Here, in closing, is a reading from a 2002 speech Prabhu Guptara delivered to a business seminar in Cambridge, England.

READER: Positive steps can be taken to ensure a good future for us all. It seems to me clear that the following steps would give us some sort of minimum agenda for creating a better sort of globalization:

inculcate a culture in which there is a high place for the idea of enough

self-restrain or penalize demands for higher wages and profits

move away from a fascination with economic expansion for its own sake

replace the notion of private limited companies with publicly authorized companies, which take seriously the environment, labor, consumers and civil society.

We need a new generation of people willing to be transformed as individuals, willing to create a new sense of community, ready to pay the cost of working for the continued transformation of our global society, and of transforming our companies from engines to make even richer those who are already rich to engines that work to produce wealth for the globe.

MS. TIPPETT:Continue the conversation at speakingoffaith.org. Contact us with your thoughts and find texts of Prabhu Guptara’s writings and speeches, including his PowerPoint about the gods of business. You can listen on demand for no charge to this and previous programs in our Archive section and subscribe to our free weekly podcasts. Now you can listen whenever and wherever you want. You can also register for our free e-mail newsletter, which includes my journal on each topic and a transcript of each previous week’s show. That’s speakingoffaith.org.

This program was produced by Kate Moos, Mitch Hanley, Colleen Scheck and Jody Abramson, with editor Ken Hom. Our Web producer is Trent Gilliss with assistance from Ilona Piotrowska. The executive producer of Speaking of Faith is Bill Buzenberg. And I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.