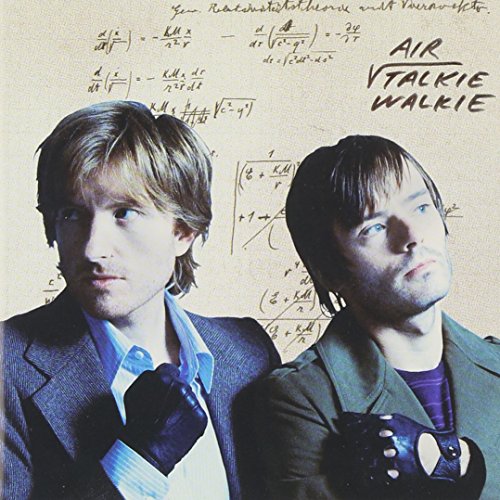

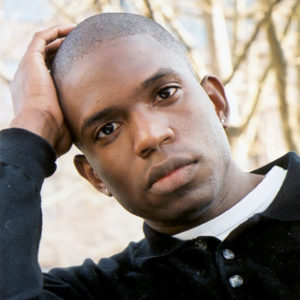

Khalid Kamau, Ellen Williams, Oana Marian, et. al.

Repossessing Virtue: Living Differently, Beyond Economic Crisis

We’re bringing the voices of our listeners into the conversation we’ve been building online and on-air since the economic downturn began last year. Many are grappling with the shame that comes in American culture with the loss of a job, and many are seeking community in old places and new. For some, economic instability — a kind of life on the edge — is not new. They’ve been cultivating virtues of patience, self-examination, service and good humor that might help us all.

Guests

Khalid Kamau grew up in Atlanta but now lives in New York City where he was a financial analyst for a nonprofit.

Ellen Williams is a cancer survivor and grandmother.

Oana Marian is a Romanian-born American citizen interested in film, poetry, and photography.

Lia Hadley is a freelance business owner focused on visual communication, educational technology, and teamwork.

Marc Mullinax is an associate professor of religion at Mars Hill University.

Emily Muschinske is a print designer, art teacher, and mother.

Transcript

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Living Differently, Beyond Economic Crisis,” a new installment in our ongoing series “Repossessing Virtue.” Hundreds of listeners have joined our conversation about the human and the practical spiritual aspect of our economic present. This hour you’ll hear eight of their voices putting words around experiences many of us are having and imparting some wisdom from disparate angles on life.

KHALID KAMAU: When I lost my job, I experienced this shame. Even though it happened really through no fault of my own, I was afraid to tell people. It was almost like contracting a disease.

ELLEN WILLIAMS: It’s sort of like the search for money has become a sacred thing, as opposed to the care and love of people, you know, and our common life together.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. This hour, a new installment in our ongoing series “Repossessing Virtue,” bringing the voices of our listeners into a conversation we’ve been building online and on air since the economic downturn began in the fall of 2008. We’ve been tracing the spiritual and moral contours of our economic present, how changed circumstances are confronting many of us with questions of what matters in life and what most deeply sustains us, what we are learning in this moment and how we might live differently beyond it to shape the next American dream. Many are grappling with the shame that comes in American culture with the loss of the job. Many are seeking community in old places and new. For some, economic instability — a kind of life on the edge — is not new. They’ve been cultivating virtues of patience, self-examination, service, and good humor that might help us all.

From American Public Media this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas.

Today — as part of our ongoing series “Repossessing Virtue” — “Living Differently, Beyond Economic Crisis,” featuring you, our listeners.

OANA MARIAN: What’s going on in the world around me is somehow now matching the way that I have been living my life for a while.

LIA HADLEY: When I think of the word “crisis,” I always think it is something we always think of as coming unexpectedly or going away quickly. I don’t think that is going to happen in this case.

KHALID KAMAU: When I lost my job, I experienced this shame. Even though it happened really through no fault of my own, I was afraid to tell people. It was almost like contracting a disease.

ELLEN WILLIAMS: It’s sort of like the search for money has become a sacred thing, as opposed to the care and love of people and our common life together.

MARC MULLINAX: Maybe we would have an American dream that is more of a right, a human right, and not just an American purchase

We received beautiful, thoughtful essays from disparate places, vocations, and spiritual perspectives. We chose a cross section of these and called people up at home or at work. They read from the stories they’d written and had a conversation with our producers. We selected eight voices who put words around experiences many of us are having and who also impart some wisdom from their particular angle on life.

We begin with Khalid Kamau. He grew up in Atlanta but now lives in New York City where he was, until January, a financial analyst for a nonprofit. He responded to our questions with this story, which we asked him to read.

KHALID KAMAU: Once when I was young, I came home after school and baked a cake for my mom for dinner. I wanted to surprise her. She’s a nurse and had been at work all day, you know, before starting her second shift as our mom. So I pulled down a box of cake mix. And after I emptied the cake mix in the bowl, I saw that the recipe called for eggs, and we were out. I remembered the stories my family would tell about growing up in the rural segregated South. Though Jim Crow blacks suffered severe institutional oppression, their communities were strong and neighbors were always helping one another out. People would come over and ask for a cup of sugar or a loaf of bread, and “if you had it, you gave it,” my mom would say.

So that day, I went across the street to Miss Jessie, our retired neighbor, who kept an eye on my brother and I in the afternoons until my mom or dad got home. I knew she would have some eggs and maybe even fondly recall the same traditions of sharing my parents spoke of. Well, Miss Jessie did have eggs and stories of her own about communities sharing their resources in the Great Depression and the segregated South. I got my two eggs and finished baking the cake.

When my mother arrived, I presented her with the cake and proudly recounted all my efforts and resourcefulness. But the glow from her face quickly faded when I got to the part about borrowing the eggs. She called my father into the kitchen, and together they scolded me about going around the neighborhood begging for food. “But I thought that’s what you guys did in the olden days,” I asked. “That was a long time ago,” my mother said. “Things are different now.”

It appears that in today’s culture, strong communities are those where estranged neighbors live on islands with no need for one another. Where sharing is not a practice of healthy community-building, but an act of last resort for the desperate and destitute. I have only once since borrowed pantry supplies from a neighbor, and they were also my best friends.

In October 2008, when the market began to collapse, I secretly hoped the crash would be so complete that our middle-class pretenses would fall with our capitalist system. Instead, what I see is a president, a Congress, and a marketplace eager to maintain the status quo. But they’re just taking their marching orders from us, the American people. It seems we’re still willing to do anything to keep from knocking on our neighbor’s door to ask for eggs.

[Sound bite of music]

KHALID KAMAU: I live in Harlem, and a lot of my friends are in finance and a lot of them have been laid off. Most of us are young and single. Our situations individually are not as desperate as things that I’ve seen go on around me, but one of the first things that happened when I lost my job is I that experienced this shame. You know, even though it happened really through no fault of my own, I was afraid to tell people. It was almost like contracting a disease, you know, that has some sort of stigma around it. But one of the things that I’ve done is now I tell everyone, you know. Probably by the end of that day if not by the next morning, like, I got up and I called everyone that I knew and I told them that I didn’t have a job. You know, I went to church at night, and I would tell people. I mean, I wouldn’t necessarily make an announcement, but it would just come up. Or I would make sure that it came up because I think there is a sort of way that people will just assume that you still have a job, and you can let people assume that.

So that’s sort of been my first step in asking for help, is to just let people know that I might need it sometime soon in the future because I don’t have a job. But it’s still hard to bring that up. I live with roommates, and sometimes we’ll buy things together or we’ll go in for purchases together, and I haven’t been able to necessarily do that all of the time and there still is some shame around that. I don’t know. I guess I work through it every day.

[Sound bite of music]

KHALID KAMAU: In this other life that I had — I was a financial analyst — I was just always busy. You know, I was too busy to do everything. And I have to say that I don’t think — though I don’t have as many material things, I feel like I have more time. And so I actually feel wealthier in a way. And one of the things we hear often in a workplace is you have to leave your personal problems at home, but very often you bring the stress from your job home, and your job isn’t really too concerned with what you’re taking home as long as you don’t bring anything back.

Now I really do just feel like a weight has been lifted. All of these worries that I had at work — which were really all about, like, paperwork and office politics and things that really in the long run don’t even matter — I am doing more chores on my own, and I’m able to pursue things like school and writing that I’m more interested in. But I also think that there is — sometimes I don’t do anything. You know, sometimes I lay in bed and watch television all day. Or I lay in bed and don’t do anything for an entire morning. I think there’s this urge and I really think it’s this capitalist urge, It’s this urge of consumption, to wherever there is an empty space that it needs to be filled with something, and we usually have to spend money to fill it.

And the same thing happens with time. I think the first week I was off I was feeling really guilty and unproductive because I had all of these extra hours that weren’t filled up with things. But I kind of decided that instead of filling them up with things that aren’t important that maybe I just won’t do anything. I don’t think necessarily that — I mean, this is the sort of thing that will sound completely irresponsible and completely lazy, but I think in some other society I don’t think that there’s really a need to fill time up just to fill it up. And I think it’s sort of made me reevaluate time.

MS. TIPPETT: Khalid Kamau of New York City. Just before we went to broadcast, he let us know that he recently took a new job as operations manager of an elementary charter school in the Bronx.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Emily Muschinske of South Orange, New Jersey, is a designer and illustrator of children’s books. And even before she herself lost her job recently, she’s watched several rounds of economic downturn in the publishing industry.

EMILY MUSCHINSKE: Publishing is an industry that’s kind of all over the map. You know, one year you’re having a good year, the next year it’s terrible and they cancel Bagel Day and they tightened up the purse strings. Nobody gets a raise. And that’s been my experience ever since my career started, so I think I’m a little bit jaded at this point as much, as I wish I weren’t. But the way you see the company and the way you see your department and your co-workers and the people who you sit next to, that’s very different.

MS. TIPPETT: Emily Muschinske is thinking a lot these days, she says, about the emotional toll that cycles of layoffs are taking, as she wrote to us, “on those of cut off suddenly from the life and people we came to know, trust, and sometimes even love.” In her essay, she posed these questions: How do we fight the bitterness, the powerlessness we feel after a layoff? How do we return to our work with an expansive open spirit ready to share our lives with new people and contribute to the group in a good way?”

Emily Muschinske has two young children, and she’s also trying to be more intentional every day about what sources of ideas and inspiration she invites into her mind and her home.

EMILY MUSCHINSKE: I really love comedy, and I always think, you know, these are people who are on this earth to make people smile and they’re committed to it. People like Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert and Tina Fey can make us laugh at what’s going on in the news. So I started pursuing these people. I started sort of searching around, you know, are there any podcasts that I can listen to? And I try to, as much as I can, take that in. And I feel like at its core laughing is so nourishing to the spirit, and that’s an act of faith right there.

You know, I have some people in my family that are survivors of the Holocaust, and it’s just really inspiring. They came through so much and they had to restart their lives. And they came to the U.S. and started from scratch and had families and raised their children and they thrived. So I try to look at that and say this isn’t even close to that scale, and hopefully we’ll come through it and we’ll recover as they recovered and as the people who survived the Depression recovered. I’m hoping that it’ll just be, looking back, a blip on the screen rather than something that defines a huge swath of your life.

[Sound bite of music]

EMILY MUSCHINSKE: There’s a tendency to feel sorry for yourself and to sort of pity yourself if you have been laid off. You know, it’s a rejection. Even if you know it’s not personal and even if your whole department got laid off and you weren’t singled out, it’s still very hard to avoid these thoughts, that somehow you’ve failed and it’s your fault. I’m trying not to go there, and there’s a choice you can make about how far you go into those thoughts. I’ve been home with my son, who’s three, a lot and he’s at this stage where he’s learning how to ask for something without throwing a temper tantrum. He wants something and he feels he has to ask for it in a whine. And you’re trying to say, “Just ask for it in a normal voice. Just ask for it and don’t feel self-pity and don’t feel sad. Just ask for what you need and it’s going to be OK if you don’t get exactly what you think you want.” So I’ve been kind of trying to apply that to myself a little bit. Just put it out there, put yourself out there, and don’t whine about it and don’t throw a fit. Just wait and something’s going to come to you. It might not be the thing that you think you want, but it’ll be something.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: to speakingoffaith.org to listen to our extended interviews with Emily Muschinske of South Orange, New Jersey, and with Khalid Kamau of New York City.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, our listeners reflect on living differently in and beyond economic crisis, part of our ongoing series “Repossessing Virtue.”

[Sound bite of music]

MARC MULLINAX: How are my students responding? I cannot get them to talk that much about it. I don’t know if they’re provided words by their faith traditions or their families on how to embrace or see themselves as part of this new day. It’s really difficult to gauge what they’re thinking when they go home for break. I don’t get a sense of the table conversations that they have at home. It often comes when I learn that someone is not coming back.

MS. TIPPETT: Marc Mullinax is a professor of religion and philosophy of Mars Hill College in the Blue Ridge Mountains near Asheville, North Carolina. He’s also an ordained Baptist minister. In recent years, he’s taken the Christian season of Lent seriously, though it was not a big part of the Protestant world he grew up in. He’s come to call it a discipline of holy interruption, which he’s now extending into other parts of his life. He’s using the notion of holy interruption as he works with his students in navigating new economic realities and prospects. In a course on human nature, for example, he uses scenes from the movie The Matrix. He challenges himself and his students to examine ways they are living virtually and not concretely and to take breaks from that, unplugging their cell phone batteries for 24 hours, for example. And beyond Lent, he’s continuing to fast one day a week.

MARC MULLINAX: I’m spending a lot more of my excess — for example, the food money I save by not eating I’m donating. I do weddings, so I ask people to donate any fees they might give to me to a local food bank called MANNA FoodBank. So it’s little things like that that that’s slowly letting creep in and interrupting the usual flow of basically how I see money. I believe the pressure from the economic crisis is certainly part of this, but since I’ve been teaching this human nature course and Socrates for the last eight years, it’s been doing this quiet number on me of examining your life and seeing The Matrix time and again and realizing that we are either agents or we are unplugged. And I don’t like to think in such dualistic terms all the time, but it helps to make those stark contrasts so that we can check ourselves out to see if we are living an examined life or life that someone else has pretty much scripted out for us and we are just puppets at the end of someone else’s strings.

One of my students, her name is Miley, I was teaching the same course in Socrates about four years ago and talked about how the unexamined life is not worth living. And she said, thoughtfully, “Well, Mullinax, if the unexamined is not worth living, does that mean that the examined life is worth dying for?” And I just got goose bumps from that.

And this is where my Christianity comes in. It’s a matter of sacrifice for the greater good.

[Sound bite of music]

MARC MULLINAX: The American dream that I grew up with, I think, is unsustainable. And I think we’ve just learned how unsustainable it is in the United States of America, but I think the rest of the world has already known it to be an unsustainable effort, where 6 or 7 percent of the population can, year in, year out, consume 40 to 50 percent of the world’s resources. That is just an unsustainable picture.

So I think we’re recognizing it maybe for the first time. And I call this a time of hope because as we are forced into a kind of Lent, as we are forced into these interruptions, maybe, just maybe there can be enough critical mass of people to see these as transforming times. That what we used to do really did not bring us closer together. It really didn’t bring justice to everybody. It really didn’t bring human rights or health care to everyone. It seemed to be a time of American dream for those who could purchase it. And maybe we will have an American dream that is more of a right, a human right, and not just an American purchase.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Marc Mullinax of Asheville, North Carolina.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Lia Hadley was born in Venezuela to Canadian parents. She grew up in Caracas, Grenada, Palo Alto, and Montreal. She’s now settled in northern Germany with her husband and children. She began her conversation with us by noting that though she considers the present in moral and spiritual and not merely economic terms, she hesitates to use the word “crisis.”

LIA HADLEY: When I think of the word crisis, I always think it denotes something that we always think of as being short-term or coming unexpectedly or going away quickly. And I don’t think that is going to happen in this case.

MS. TIPPETT: Lia Hadley currently has work she loves at a computer science research institute on a project to implement digital media into K–12 classrooms, but she makes her living as a consultant and she is facing unemployment when this project ends. A dramatic downturn in her economic outlook actually came nine years ago with the IT crash of 2000, and she has been adjusting her understanding of work, money, community, and life ever since.

LIA HADLEY: I read recently that there are a hundred million photos that people can access and use on Flickr alone, and a hundred of my collages are a part of that hundred million. And I know, about two years ago or three years ago, when Kiva started — this as a microfinancing blog where you can — or a platform where, as individuals, you can contribute to entrepreneurs in third-world countries. So I helped this shop owner in Ukraine, and in the proceeding two or three years it came to a point where now I’m setting up microfinance businesses with women in Kenya and Rwanda and Uganda and Cameroon. I just find that because of these people who have shown me that you don’t have to be an expert or you don’t have to be powerful or even necessarily particularly smart, everyone can just redefine what it is to live successfully in a community.

My grandmother, she was the all-time community worker. She was this Irish Catholic woman living in Quebec, and of course the Church was bigger than politics. It was everything. And so her community was a church community. I mean, my community is literally the elderly neighbor living across the street or the young neighbor living in the orphanage in Kimilili, Kenya, that I’m working together with. I mean, it can be very loose and broad.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Listen to longer interviews of the two guests you just heard, Lia Hadley of Lübeck, Germany, and Marc Mullinax from Asheville, North Carolina, on our Web site, speakingofffaith.org.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: What started out as an online project last fall has resulted in several radio programs, including this show with our listeners, but the conversation does not stop here. We’ve crafted a dynamic map, weaving together a rich tapestry of stories and audio, images and geographies from the hundreds of people who have written to us, including a listener from Thailand who finds solace in the annual Thai celebration releasing paper lanterns with prayers. And Careen Stoll, a potter from Portland, Oregon, who says she feels needed as never before in this new economy. Add your own perspective at speakingoffaith.org and download other shows from our series “Repossessing Virtue.”

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: After a short break, the stories and wisdom of a Romanian-American filmmaker, a Mennonite businessman, a Muslim student of economics, and the poetry of Wendell Berry.

I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett.

Today, a new installment in our ongoing series “Repossessing Virtue,” bringing the voices of our listeners into a conversation we’ve been building online and on air since economic downturn began in the fall of 2008. We’ve been tracing the spiritual and moral contours of our economic present, how changed circumstances are confronting many of us with questions of what matters in life and what most deeply sustains us, what we are learning in this moment, and how we might live differently beyond it, shaping the next American dream.

We heard from hundreds of listeners, often in the form of beautiful, thoughtful essays. We called people up at home or at work. We chose eight voices for this hour who put words around experiences many of us are having and who also impart some wisdom from their particular angle on life. Abeer Raazi of Columbus, Ohio, is just about to graduate from college with a degree in economics. He wrote this to us:

“I have seen problems looming for my generation grow from hurdles into mountains before my eyes: the tensing political and economic climate, the wracked Social Security system and my parents that it might not be providing for, the severe economic limitations of oil, water, and food. Sometimes it feels like I’m in over my head and the anxiety gets to me. These problems have really provoked me and have got me questioning many of the assumptions I was raised with.”

He continues, “My religion, Islam, teaches me to hold my material possessions in my hand and not my heart. It teaches me to count my wins and my losses as one, both important facets to a far more important journey.”

Abeer Raazi.

ABEER RAAZI: So initially I was interested more in international relations and politics, and I thought the way to understand that best is to follow the money. And naturally that led me to economics. So when I started studying the discipline, I was pretty disappointed in that it didn’t really shed much insight into what’s happening in the world. It was very disconnected from real-world phenomena. And when you sort of tap into that economic world of academics and finance and corporations, then you understand what sort of principles are driving these people. And if you have a critical perspective, you see how that relates to society and politics. But you need that critical perspective to be able to do that, since the discipline it doesn’t do it itself.

As a Muslim, I naturally draw heavily from the Islamic tradition, and it’s reflecting a lot on the Qur’an, which heavily emphasizes the temporary nature of this life and death and preparation for the next life, which many of the spiritual traditions do. And I think associating that type of heavy spirituality with the founders of the discipline like Adam Smith and their ambition for social betterment — he’s written quite a bit on that — and on social allocation. And he wrote in The Wealth of Nations often that the invisible hand that you hear of so often nowadays, it often fails and that we need to reconcile for these failures. And he acknowledged that. And he wrote an entire book on the theory of moral sentiments, which is an interesting secular book which creates a whole system of ethics which is forgotten in applying economics nowadays. And I think that’s really sort of keeping that perspective on what’s important and trying to apply the tools in that direction. That’s some of the change we need to be making.

[Sound bite of music]

ABEER RAAZI: Personally, I want to do something where I’m changing communities. So there’s a few things I want to learn about microfinance. In fact, I’m going to be going to Pakistan in a few months to work with a microfinance organization so that’s going to be an interesting experience. And specifically I’d also like to study my religion a little more, Islamic intellectual tradition. It has a very strong intellectual tradition but it’s been lost for, you can argue, several decades or a couple centuries. But it’s certainly been lost, and I’d like to get back in touch with the primary sources, the different ways they’ve been applied to different times. Pakistan is probably — I think it is the first country where microfinance was started by a man named Akhtar Hameed Khan, and so it’s being heavily applied there and a few successful models. And so I’ll be going to work with a couple of those. In fact, they’re applying it to cities. You often hear of microfinance being applied in rural areas, but it’s working in some — they call it kachi abadi — the slums around the big cities. So I want to go see how that works.

It’s interesting, you know, now we see in America these tent cities popping up in Sacramento and it seems like things are just going to get worse, so this might be a tool we can even utilize here at home.

MS. TIPPETT: Abeer Raazi of Columbus, Ohio.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Ellen Williams was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer around the same time the economic crisis hit. Her medical bills skyrocketed, in other words, as her investment income dropped. As she’s weathered these multiple crises, she’s read widely and pondered questions of meaning. She’s become increasingly aware, she wrote in her essay to us, of how we define ourselves in American society by signifiers, she calls them, of age, gender, accomplishments, education, and membership. She’s intrigued by one of the questions we’ve been posing to listeners these months. With the economic crisis in mind, who will we be for each other? But Ellen Williams insists that who we will be for each other will flow out of a more basic question: Who am I?

ELLEN WILLIAMS: Based on who I am, that is how I treat other people. And the basis of any spiritual discipline begins with compassion, kindness, fairness, and it seems to me that those virtues, those spiritual concepts, have been basically lost sight of lately. But the other aspect of that is when one has a personal crisis, whether it’s caused by health or whether it’s caused by economic loss or whatever, then you do have to ask yourself again, “Well, who I am? How do I handle this based on who I am?” If who I am is only what I own or it’s only the amount of money that I’ve saved and then lost, or the job I’ve lost, if that’s the only thing that’s grounding one’s sort of faith on, then it really is a crisis. So even in the midst of my crisis —which is a health crisis, but is also a financial crisis — I’ve been lucky to still get very good care. I have to think, you know, what are the things that really sustain me? What are the things that are really important to me? And not only focus on whatever things that I have lost, whatever identity I might have lost through it.

MS. TIPPETT: Ellen Williams is Episcopalian, and she’s also been a practitioner of meditation across the years. She says that these dual traditions are helping her live through extremely difficult experiences in the spirit of one of her favorite poems by Wendell Berry. It is called “The Peace of Wild Things,” and it goes like this:

“When despair for the world grows in me and I wake in the night at the least sound, in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be, I go and lie down where the wood drake rests in his beauty on the water and the great heron feeds. I come into the peace of wild things who do not tax their lives with forethought of grief. I come into the presence of still water. And I feel above me the day-blind stars waiting with their light. For a time I rest in the grace of the world and am free.”

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, our listeners reflect on “Living Differently, Beyond Economic Crisis,” part of our ongoing series “Repossessing Virtue.”

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Oana Marian lives in Los Angeles. Her family immigrated to the U.S. from Romania when she was eight years old. Like so many of the people who wrote to us, our query about changed life in and beyond economic crisis spurred Oana Marian to write about humanity and community. She told of the generosity of one elementary school teacher in particular named Mary, who took her and her mother under her wing when they were settling in the U.S. and whose practical kindness has shaped the way she has lived ever since.

OANA MARIAN: Actually, the most poignant part of that story was my mom was sort of overwhelmed with a feeling of indebtedness, and Mary wrote my mother this note once that said, “Please don’t ever say again how I don’t know how I’m every going to be able to repay you.” She said, “What else makes sense in this crazy world if we’re not helping each other?” So she just was kind of a genuine angel, and we’re still friends with her. We have Christmas and Thanksgiving with her family every year.

So what that means for me now is that — I’ve moved around a lot in the last two years but wherever I’ve gone I’ve tended to seek that. While I was in Italy, I met this chef who lives in Los Angeles and when I came back to L.A. a year and a half ago I started working for her as her personal assistant and also working at her restaurant. For me, working at that restaurant is like having a family in Los Angeles.

MS. TIPPETT: That family at work is more important to Oana Marian than the salary she makes, she says, though it barely sustains her as she struggles to create a career as a filmmaker. She writes, “I work in the film industry, an industry defined by uncertainty, risk, dreams, and largely egotistical ambitions. For the nonunion filmmaker there is no health insurance. Paid work comes unexpectedly or not at all. Rewarding work is sporadic. But great communities are possible as a result. There’s a tenuous sense of meaning in all this, and I can honestly say that during the past five years I have had the fullest, most enriching experience of my life though I was broke or badly bent the majority of the time.” Oana Marian.

OANA MARIAN: In some ways I feel what’s going on in the world around me is somehow now matching the way that I have been living my life for a while. I mean, for my entire adult life. So it’s hard for me to say that I’m living any differently. But in some ways, there’s some comfort knowing that more people are asking the same questions that I’ve been asking all of these last years because I’ve been living in kind of an insecure world of my own. And suddenly the cracks start to show. And then in some ways, you fee like, OK, I haven’t been crazy this whole time. For example, maybe it’s a silly example, but this overwhelming idea in Los Angeles that you can’t get around without driving. Well, you can get around. There actually is the subway that most people who live here don’t know about. There’s public transportation. So even before the cracks started showing, to try to live in a simpler way even in a complicated environment, I think that this feeling that a lot of people have that suddenly everything is going to fall apart and there’s nothing we can do, you know, there are very simple solutions. And I think that that’s what happening more now as the structures that we trusted and that were the foundations of how we maneuvered our lives, that these are kind of falling apart. In some ways, I’m hoping that one of the results of that is that people will realize the value of human relationships. And what it can mean to be in Los Angeles and to work at a restaurant like Angeli, that it’s not about the money and that you have this community of people who will stand behind you and will be there and will come to your screening when you have your first movie out. This is what seems really necessary to me right now, is finding people who have the real ability to build a community.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Oana Marian of Los Angeles, California. She concluded this essay to us with this sentence, which is counterintuitive, perhaps, in a moment of economic uncertainty but which echoes other younger people who wrote to us. “It is an exciting time to be alive. Almost overwhelmingly exciting.”

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: We hear finally from Jim King who lives in Telford, Pennsylvania, where he is president of an industrial scrap plastic recycling company. He finds sustenance in a weekly gathering of businessmen he attends where they have recently spent much time in discussion and supportive strategy on the repercussions of economic downturn both practical and personal. Jim King is also a devout Mennonite, and he routinely participates with his family in Mennonite social service projects.

In response to our question about moral and spiritual aspects of economic crisis and how we might live differently in and beyond it, he sent this story.

JIM KING: Several weeks ago I went with 12 other men to Benton, Kentucky, with our chainsaws to work with Mennonite disaster service, cleaning up properties for mostly elderly people who had been affected by a recent ice storm. I was asked by a local person there why we were doing this. Why did we come all the way from Pennsylvania to help them? I responded that back home our economy is not doing well either. In fact, several of the Amish men in my group were presently out of work because the construction industry is at a standstill. And since their companies were not expecting a bailout, why not use the time to go give someone else a bailout? What better stimulus is there than to help a neighbor in need, even if they are 800 miles away? To me, seeing the joy in an elderly person’s face and listening to people’s stories about the ice storm was ample reward. Hearing 12 chainsaws in a back yard is stimulus enough for me.

[Sound bite of music]

JIM KING: I look at it as maybe we lost or ignored our spiritual compass. I think we assumed we had the right to drive whatever type of vehicle we chose, buy a house larger than we could afford, and then fill it with things we can barely use. So now we come to find out our environment can’t take it anymore, and we can’t afford the bills, either.

I have to think back now when I was in Sunday school as a child, we used to sing that song. It went something like this: “Wise man built his house upon the rock. The wise man built his house upon the rock, and the rains came tumbling down.” Then that song goes on to describe what happened to the foolish man who built his house upon the sand, and I think about now a lot of us are feeling a little foolish for what we had our faith in.

I look back now and think of the times that we as a family worked in the garden, and this year I’m planting a bigger garden. And I enjoy taking care of it anyway. I know that the food pantries in my community will need the extra food I have and it’s a hobby. And also, I think as I look back on my childhood, I was raised in a family that we were taught to manage our money as children fairly well, and I want to work on that with my family, and sometimes that’s a struggle. My son wants the same things that he sees other people have. And at the same time, I don’t want to come across as being stingy. I want to be generous in an environment like this. The world needs people who are generous and willing to look out for each other.

[Sound bite of music]

JIM KING: We’ve had a family meeting at home a couple of times and have discussed how the world is different than it was in 2007 and what is it we’re going to do about it. And a couple of those things was planting a bigger garden, turning off lights in a room if we’re not using it. It has to be pretty simple, pretty basic. Otherwise, we lose sight of the bigger picture, or it seems like we’re not making a difference anyway. And I’m not only looking for leadership, but I think we have the challenge to be leaders. We have the challenge to find a new perspective that might challenge us to live differently. I see it as the beginning of a new American dream. This is now the opportunity for us to get it right.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: You can listen to longer interviews with Jim King of Telford, Pennsylvania, and with the other voices you just heard: Oana Marian from Los Angeles, Ellen Williams of Richmond, Virginia, and Abeer Raazi from Columbus, Ohio, and all the voices of this hour on our Web site, speakingoffaith.org.

“Repossessing Virtue” began as an online project, as our way of exploring the moral and spiritual aspects of economic crisis, reaching out to former guests on the program and to you, our listeners. We quickly decided to showcase these evocative, helpful conversations on our Web site and to turn them into a series of radio programs. Listen to the other two programs we’ve created with Quaker author Parker Palmer and with a range of wise voices from religion, science, industry, and the arts. And find other stories and perspectives from all over the world by way of our dynamic map. We’d love for you to tell your story while you’re there. All of this is possible at speakingoffaith.org.

And on May 20th, I’ll have a live public conversation with President Obama’s director of faith-based partnerships, Joshua DuBois. That will take place in St. Paul, Minnesota, and we realize many of you can’t attend in person but that doesn’t stop us from including you. We’re bringing the event to you online. Watch a live video stream of that conversation and submit your questions in real time. We want as rich a conversation as possible. Sign up on our Web site to tell us how you’d like to participate and to be on our list for reminders about details as the event approaches. Look for links on our homepage, speakingoffaith.org.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: The senior producer of Speaking of Faith is Mitch Hanley, with producers Colleen Scheck, Shiraz Janjua, and Nancy Rosenbaum, and with help from Larissa Anderson. Our technical director is John Scherf; our online editor is Trent Gilliss, with Web producer Andrew Dayton. A special thanks for this program to Counterpoint for permission to broadcast Wendell Berry’s poem “The Peace of Wild Things,” from The Selected Poems of Wendell Berry. This program is part of the “Next American Dream” series from American Public Media. Kate Moos is the managing producer of Speaking of Faith. And I’m Krista Tippett.