Ross Gay

On the Insistence of Joy

In our world of so much suffering, it can feel hard or wrong to invoke the word “joy.” Yet joy has been one of the most insistent, recurrent rallying cries in almost every life-giving conversation that Krista has had across recent months and years, even and especially with people on the front lines of humanity’s struggles.

Ross Gay helps illuminate this paradox and turn it into a muscle.

We are good at fighting, as he puts it, and not as good at holding in our imaginations what is to be adored and preserved and exalted — advocating for what we love, for what we find beautiful and necessary. But without this, he says, we cannot speak meaningfully even about our longings for a more just world, a more whole existence for all. To understand that we are all suffering — and so to practice tenderness and mercy — is a quality of what Ross calls “adult joy.” Starting with his cherished essay collection The Book of Delights, he began to accompany many in an everyday spiritual discipline of practicing delight and cultivating joy.

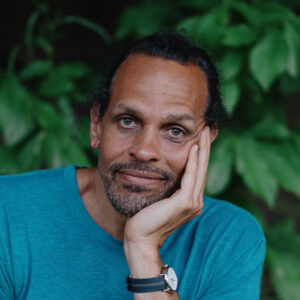

Image by DEEN, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

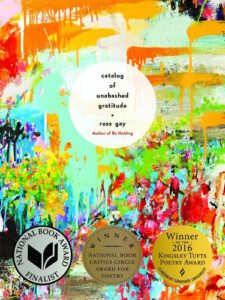

Ross Gay is a poet, essayist, teacher, and passionate community gardener. He lives in Bloomington, Indiana, where he’s a professor of English at Indiana University. His books include The Book of Delights, The Book of (More) Delights, and Inciting Joy, as well as the poetry collections Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude and Be Holding.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

Krista Tippett: In our world of so much suffering, it can feel hard or wrong to invoke the word “joy.” Yet joy has been one of the most insistent, recurrent rallying cries in almost every life-giving conversation I’ve had across recent months and years, even and especially with people on front lines of humanity’s struggles.

And Ross Gay helps illuminate this paradox and turn it into a muscle.

We are good at fighting, as he puts it, and not as good at holding in our imaginations what is to be adored and preserved and exalted — advocating for what we love, for what we find beautiful and necessary. And without this, he says, we can not speak meaningfully even about our longings for a more just world, a more whole existence for all. I love this wisdom of Ross: that we practice tenderness and mercy in part because to understand that we are all suffering is a quality of what he calls “adult joy.” He is a poet and essayist and teacher, a passionate community gardener, also a former college football player. Beginning with his cherished essay collection The Book of Delights, he began to accompany many in learning — I would say as an everyday spiritual discipline — to practice delight and cultivate joy.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Ross Gay lives in Bloomington, Indiana. His other books include Be Holding, Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude, and Inciting Joy. This conversation unfolded live at The Loft Literary Center’s 2019 Wordplay Festival.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Tippett: So here we are. And what we’re going to do is, I have these three beautiful books…

Ross Gay: Great.

Tippett: …and if at any time you just feel called to read something, you may.

[laughter]

Gay: Okay. I’m like, that might happen a lot — [laughs] the whole time.

Tippett: That’s all right. We have about an hour. We’re going to be in conversation up here, and it is my plan that at the end, I’ll have you read a few things. But I just want to give you that opportunity for spontaneity.

Gay: Okay.

Tippett: So you grew up between — you said you were born in Youngstown, Ohio, and grew up in Levittown, Pennsylvania; a lineage of farmers and teachers. So interesting to me, also, your parents were a mixed-race couple; I guess they got married in the era of Loving vs. Virginia. You write a lot about how your mother, especially as she got older — your mother was white, your father was Black — that she started to talk about what it was like to get married then. And I feel like that’s such an important story that we tell ourselves because things have changed so much in that regard, at least. Say a little bit about what you got from what your parents — just your parents getting married meant.

Gay: It’s sort of amazing to me. My mother — yes, as I say, she’s talking more about their life together, which was many things, and among them was this sort of difficulty that mostly, they didn’t talk about. And that’s — I realize, that’s part of my — one of the many things that I’m constantly curious about: what was it like? And my mother does tell some things now, but I sometimes think of their experiences, and I’m just sort of curious about, what were the sorrows that they were just not —

Tippett: And also, that people would say to her, “Of course, you can do this; and just know you’ve doomed your children.” Right?

Gay: [laughs] Yeah, totally. Totally. My mom, she says, “Yeah, Aunt Sylvia, she’s the one who said it was going to be fine.”

Tippett: [laughs] Oh, okay, yay. I just wanted to name that, because it’s almost like she’s a first gen — it’s like the first generation of trauma; first generation of people who make it through something that feels unimaginable often don’t talk about it. And now we’re in such a different place with that, but that’s also part of the story of how we got here.

Gay: Right, yeah.

Tippett: So your last two books are The Book of Delights and the Catalog of Unabashed Gratitudes. I usually start my conversations by asking about the spiritual background of someone’s childhood, however you would think about that now. I’m really curious, with you, where you trace the origins of being attuned to delights and unabashed gratitudes. Where does that come from?

Gay: That’s a really good question. To some extent, I feel like — I feel like I’ve always loved the smell of honeysuckle. [laughs] I feel like I could love stuff, really love stuff. I feel like — and I feel like I’ve had periods in my life where it’s been harder to be like that.

But I also feel like my folks modeled a certain kind of — I recently remembered this story, and I will never un-remember it, that my dad told us, me and my brother. We were in the car, and I guess we wanted to push the windshield wiper fluid button. And my dad wanted us not to, and told us that if we pushed it — he said that picture on there was a flower, and the car would turn into a flower…

[laughter]

…which makes him, like, a hero. And then he said, “And a big bee will come and sting you.” [laughs]

[laughter]

Tippett: That’s so great.

Gay: But it’s amazing, right?

Tippett: Right. Right.

Gay: And I kind of —

Tippett: That it wouldn’t turn into a monster —

Gay: Wouldn’t turn into a monster. But that was like, for years, I actually thought that that button made — and so any time I look at that button — not any time, but often, when I look at that button, I’m like, “Oh, that’s a flower.” And for years, I did believe it would turn — and I gotta ask my brother, too, if he also thought that for years.

But I don’t know, I feel like in some way, my folks did some of that for me.

Tippett: And just were like that.

Gay: In some ways — and in some ways not, too. In some ways, just going to work and taking care of stuff and boom boom boom boom boom boom boom. But I know that the older I get, the more I can point to things that were, like, “Oh, yeah. My mother was really good at that. My father was really good at that. My brother was really good at that.”

Tippett: Was her family from Minnesota? And they were farmers.

Gay: Yeah. Verndale, Minnesota.

Tippett: Verndale, Minnesota.

Gay: Anyone from Verndale? [laughs] No. No. [laughs]

[laughter]

Tippett: No takers.

Gay: There’s 500 people in Verndale.

[laughter]

Tippett: I kept thinking when I was reading you and getting ready to be with you, about how sometime last year, I was at a gathering of a lot of philanthropists and leaders of nonprofits, people who are doing good in the world and want to do good in the world, and someone said to me — one of these people, who was in a position of leadership, said — “How can we possibly be joyful in a moment like this?” And I feel like your entire body of work, and what you’re articulating as you also navigate this moment we live in is a response to that, and is strangely countercultural — to see joy — I would say, as just a simplified way, and I want you to expand on it — but to see joy as a calling, precisely in a moment like this.

Gay: And that’s the thing. It’s like joy — sometimes I think there’s a conception of joy as meaning something like — like something easy. And to me, joy has nothing to do with ease. And joy has everything to do with the fact that we’re all going to die. That’s actually — when I’m thinking about joy, I’m thinking about that at the same time as something wonderful is happening, some connection is being made in my life, we are also in the process of dying.

That is every moment. That is every moment.

Tippett: Say some more about that connection for you.

Gay: The connection between the dying and the joy? Well, part of it is just the simple fact of the ephemerality of — and maybe this is a little veering off, but there is this thing of like if you and I know we’re each in the process, [laughs] there is something that will happen between us. There’s some kind of tenderness that might be possible — not always going to happen because I might just get scared and do something else. But there’s the potential, I think, for some kind of tenderness. And this is the thing that’s been interesting about writing that Delights book, is that it has sort of articulated for me a way that, “Oh, my question is joy.” My question that I could see that’s a life question is, “What is this joy?” Or, “How joy?”

But in the process of thinking about it, I have really been thinking that joy is the moments — for me, the moments when my alienation from people — but not just people, from the whole thing — it goes away, and it shrinks. If it was a visual thing, like, everything becomes luminous. And I love that mycelium, or forest metaphor, that there’s this thing connecting us. And among the things of that thing connecting us is that we that have this common experience; many common experiences, but a really foundational one is that we are not here forever.

And that — that’s a joining, a joy-ning. So that’s sort of how I think about it.

Tippett: And is a common experience also our capacity for joy, in and through and despite that?

Gay: Say it again?

Tippett: So one thing that bothered me about this idea that joy couldn’t be possible is that joy is somehow a luxury or a privilege.

Gay: That’s just fucking dumb.

[laughter]

Tippett: It seems to me that joy — Okay, we can’t put that on public radio, but okay.

[laughter]

Gay: Oh, yeah, sorry.

Tippett: But joy is — our capacity for joy, despite and through that, the fact that we’re all going to die and that things are going wrong all the time, is also something that joins us together.

Gay: Totally. Totally.

Tippett: It’s leveling, in a way.

Gay: And it’s sort of like it is joy by which the labor that will make the life that I want possible. It is not at all puzzling to me that joy is possible in the midst of difficulty.

Tippett: So The Book of Delights, you promised yourself to write a mini-essay every day, starting on your 42nd birthday, going into your 43rd. You did miss a few days, but you did it for that whole year. I’m just saying, there are not 365.

[laughter]

Gay: I missed, like, the fourth day. I know, I know.

Tippett: [laughs] And you love words, and I love words, so I just want to — we’re gonna get into the book, but just tease this out. I did not know that the word “essay,” in French, means “to try” or “to attempt” — that’s so great.

Gay: Isn’t that great? And when you tell — it’s the best thing, when I tell students who are having to write essays —

Tippett: Anguished about writing an essay.

Gay: Oh, my God, they’re just like, “Well, why am I doing what they’re telling me to do all the time? Or why are they telling me to do this; ‘Have a thesis, and then tell us why the thesis is true’?” No, don’t do that. Just try.

Tippett: And then you also point out that “delight,” the word “delight,” suggests both “of light” and “without light,” which kind of points back at what you were just talking about.

Gay: Exactly, exactly. The delightful things that I’m talking about in this book, so often, when they’re there, they also imply their absence.

Tippett: Have you thought much about what is the distinction between delight, pleasure — I don’t know. Something people talk about a lot now is gratitude, a practice of gratitude. And it strikes me that this practice of daily delight is — has a kinship with that, but it’s slightly different. I don’t know. Did you think about what really focusing on the word “delight” meant, for you?

Gay: It just came in my ear. Something delighted me, and I was like, “Oh, it’d be a neat thing, to write essays every day for a year about something that delighted me.” It came in my ear. It wasn’t until literally the last day of writing that someone sent me a card for my birthday and told me what the etymology of delight was. And I was like, “Oh, I didn’t even look up the word yet.”

[laughter]

I mean, I kind of know what it means, but obviously, part of the fun was inventing what it meant, too, and sort of theorizing it, despite having not looked it up.

Tippett: So what surprised you, in the process of moving through that year and moving through that year looking for delight and writing about delight every day?

Gay: Many things surprised me, I suppose. But one of the things that surprised me was how quickly the study of delight made delight more evident. That was really quick. [laughs] And I wasn’t sure; I was a little bit like, “This is going to be hard, to just have something delightful happen every day.”

[laughter]

Tippett: You said somewhere that you developed a delight radar or a delight muscle. Well, it seems to me it’s kind of the inverse, or the opposite experience from going to the therapist every week, where you’re saving up things [laughs] that illustrate your neurosis. And you were doing the opposite.

Gay: Exactly, exactly. Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. And it’s fun. It was fun.

Tippett: But what are some of the things that you noticed that you found delightful and called “delight” that you wouldn’t have imagined before you started?

Gay: You know. It just occurred to me — it made me realize, too, how often I am delighted, how often things happen that — like you were doing this hand gesture, and you were doing these hand gestures. I was like, “I love hand gestures,” when you were doing that. I do them too, with abundance.

[laughter]

I realized, over the course of writing the book, how much I love — I have a title of one of the pieces in there, but it’s like — how do I say it? “Physical contact that is pleasant, unambiguously pleasant” — “public physical interactions,” I think is what I call it. I love how frequently I’m in the presence of sweet little interactions that don’t have to happen but do have to happen.

Tippett: I guess some that I noticed — just these ordinary things, like seeing two people sharing the burden of carrying a shopping bag or a sack of laundry, how they are helping each other and how their bodies are adjusting to each other.

Gay: [laughs] It’s pretty amazing. It’s an amazing thing.

But it’s not, until you say it’s amazing.

[laughter]

“Whoa, that’s amazing. We do that all the time.”

[music: “Le Marais” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I think sometimes about this phrase, “made my day” — that we have the power, with our words and with all kinds of small gestures like that. Even somebody being really nice in a checkout line, or you being nice to somebody in a checkout line after the last two people were really rude to them. And you watch a transformation take place that you made — that their day was getting broken, and you made. What an incredible power we have, to walk through the world, making somebody’s day.

Gay: Just in a soft way. It’s kind of amazing.

Tippett: There’s also a lot of café runs. [laughs]

Gay: [laughs] That’s something too — I was like, man, I drink a lot of coffee.

Tippett: There’s a lot of the vegan donut that you haven’t eaten yet, but it’s already delighting you, just the thought of getting to it. [laughs]

Gay: Totally. That’s right.

Tippett: And also, arugula and greens and garlic from your garden.

Gay: Yeah, my garden, and it’s funny, because people, when they talk about the book, they notice the garden as a primary feature of —

Tippett: The garden is actually a character in the book.

Gay: And it didn’t occur to me, probably because it’s so much — the garden is so much in my life.

Tippett: Well, I’d like to talk about that, because I also feel like the garden becomes, not just a metaphor, but a way that you also work through the complexity of these ideas about joy and delight and what it means to be alive and in relationship.

Tell us about the Bloomington Community Orchard.

Gay: So that’s — the Bloomington Community Orchard is this public orchard that was started by a woman named Amy Countryman. And she gathered a bunch of people, and basically — well, actually, the cool story is that she wrote a thesis project, an undergraduate thesis project, which her advisor suggested she take to the urban forester. Bloomington’s a pretty little town, so everyone, in that way, kind of knows each other. And the urban forester says, “Well, it’s a good idea. If you can show support” —

Tippett: And we’re in Bloomington, Indiana.

Gay: Yeah, Bloomington, Indiana. And the urban forester said, “It’s a good idea. If you can show support, we’ll give you a little seed money and let you use this acre of land” that they were just mowing, anyway. And she had a callout meeting; a crowd like this showed up; and boom, boom, boom, I don’t know, several months later, we were planting an orchard. And it’s this amazing place, and maybe there’s 100 fruit trees, all kinds of fruit trees.

Tippett: Which is so amazing — 100 different kinds of fruit. But it’s not huge, right?

Gay: No, no, no. It’s an acre. It’s a football field in size.

Tippett: And it was a dead zone, before.

Gay: It was just lawn. It was just lawn, super-compacted lawn. So it’s a benefit to the city that we’re managing this property now, and obviously, it’s a benefit to the community. And I think it’s a magical place, because it’s trees, and it’s wonderful, and it makes some food, but it’s — the real beautiful thing, to me, about it is that there’s so much learning and community building going on in there. It doesn’t actually make a dent into food security in what it produces. That’s not what it produces. What it produces is the community coming together, the sharing of knowledge, all that kind of stuff.

Tippett: But it does sound like it’s a place where anybody can walk up and take a piece of fruit…

Gay: You can walk right up.

Tippett: …which is not nothing. It’s not food security, but it’s nourishment.

Gay: Oh, totally. Oh, yeah. Absolutely, yeah. It’s not bushels and bushels and bushels and bushels is what I’m saying.

Tippett: I love — I think this is a line from the website: “free-fruit-for-all” — this is big adjective — “free-fruit-for-all food justice and joy project.” [laughs]

Gay: It’s pretty good. It’s pretty good. It’s amazing. Probably hundreds and hundreds of people have taken classes at the orchard, and those people then go and take that information wherever they do, either to their neighborhoods or some other orchard or whatever. So that is a pretty wonderful project.

Tippett: What trees do you head for when you go to the orchard?

Gay: Our blackberries always do really good, so I’m pumped for the blackberries. We have a fig tree, and I always check on the fig tree, because it came from my buddy’s dad’s yard back in Levittown, Langhorne, Pennsylvania. And it’s always a little tricky for the figs to ripen up, in Bloomington, because it’s — because it’s Indiana. But sometimes they do, and they’re incredible. And we have good apples. And it’s organic, so everything looks like a real piece of fruit. [laughs]

[laughter]

Tippett: You’ve said that when you started growing things, your life got better.

Gay: Yeah. For one, it’s just fun to be in a garden, for me, dreaming about what could happen: that kind of mystical space, actually, of trying to figure out what this thing that I do here could be in five years; that kind of strange dreaming space that it is. There’s also something really moving about putting a seed in the ground and it turning into something really different, and a lot of something really different and, potentially, on and on and on, a lot of something very different.

I’m crazy for smells, and a garden gives you smells. [laughs] I’m nuts about that. I’m nuts about that.

And I know the soil makes you happy, too, put your hands in soil. We know that. There’s many things. To walk out your door and get a little food — I can go on and on about this.

Tippett: No, no — that’s great. This is an example of pointing out delights, lingering with small things that are actually pretty big.

Gay: Totally. That’s what I think when I look at a flower, whatever the flower is. We’re growing a really nice crop of dandelions right now.

[laughter]

And just this year, I was like, “It’s a crop. It’s a crop.”

But anyway, if you spend time looking at the flower, any flower — or anything, but — and gardens give you the opportunity, because they also make you want to smell them and maybe taste them and all that — it’s like, I’ve never seen anything.

And you can do it again and again and again and again and again. It’s crazy to me. Anyway, so you can tell, yes. It’s made my life better.

Tippett: Well, what also strikes me when you write about the garden is public space is also something you care about, you go around looking for, thinking about. I share that with you. And it strikes me that the gardening flows into that in interesting ways, because it’s also when you write about it — here’s a place where you’re writing about that it’s such a study in the interrelationship of things, and how if you put something here, it might not happen, and if you put it near this, it might not happen; but if you put these two things together — so there’s this kind of — there’s this real rigor and sophistication that goes into it. And then there’s also so much unexpected that happens.

Gay: Totally. And actually, when you said that, it made me think too, talk about public space, that — it’s also a thing that the orchard, you can always walk into the orchard. I want to say that because so much space becomes private these days — that to have a space that you can just go there, you just go there, no just go there — it’s a big deal.

Tippett: Well, just how the garden, the complexity — well, it is. It’s a little microcosm of wholeness and the complexity of wholeness and the interrelationship of things.

Gay: Yeah. Totally, right. And you’re constantly imagining, “Well, what if this was here? And what if this was here? And what if —” I’m always trying to think of ways to interact with bugs, say, that eat my plants, and “What if we had these things here? What if we invited these things into the garden?”

Tippett: And then you have to think about what you know about what will happen if you put that there, and if you put it there on its own or if you combine it with something else.

I do love thinking about an orchard as public space. I think a lot about how we conflated public life with political life in this culture for so many years, and that’s so narrowing. And this is a way of opening that wide, what can public space be — a place where anybody can go grab some fruit.

Gay: You can just be. That’s a thing, to have a place where you can go hang around and not be told to leave.

Tippett: It’s not necessarily so purposeful or agenda-driven, which is what we’ve done with public space.

Gay: Yeah. Totally. Yeah.

Tippett: I wanted to —

Gay: Can I read one?

Tippett: Yes, please. Do you want this? Or — you’ve got it.

Gay: It’s called “Loitering.” It fits what we’ve been talking about.

“Loitering” — I curse a lot in this one. I can’t read it.

[laughter]

Tippett: [laughs] No, you can read it. You can read it here.

Gay: I can?

Tippett: Yeah, read it here. Yeah, read it. It can be on the podcast.

Gay: I was thinking, “If this is on” — I curse a lot. I just do. And I was thinking, “Oh, boy.”

“Loitering”

“I’m sitting at a café in Detroit where in the door window is the sign with the commands

NO SOLICITING

NO LOITERING

stacked like an anvil. I have a fiscal relationship with this establishment, which I developed by buying a coffee, and which makes me a patron. And so even though I subtly dozed in the late afternoon sun pouring under the awning, the two bucks spent protects me, at least temporarily, from the designation of loiterer, though the dozing, if done long enough, or ostentatiously enough, or with enough delight, might transgress me over.

“Loitering, as you know, means fucking off, or doing jack shit, or jacking off, and given that two of those three terms have sexual connotations, it’s no great imaginative leap to know that it is a repressed and repressive (sexual and otherwise) culture, at least, that invented and criminalized the concept. Someone reading this might very well keel over considering loitering a concept and not a fact. Such are the gales of delight.

[laughter]

“The Webster’s definition of loiter reads thus: ‘to stand or wait around idly without apparent purpose,’ and ‘to travel indolently with frequent pauses.’

Tippett: [laughs] That’s so —

Gay: “Among the synonyms for this behavior are linger, loaf, laze, lounge, lollygag, dawdle, amble, saunter, meander, putter, dillydally, and mosey. Any one of these words, in the wrong frame of mind, might be considered a critique or, when nouned, an epithet (‘Lollygagger!’ or ‘Loafer!’).”

Is “lollygag” a Minnesota thing? Because my mom says that all the time.

“Indeed, lollygag was one of the words my mom would use to cajole us while jingling her keys when she was waiting on us, which, judging from the visceral response I had while writing that memory, must’ve been not quite infrequent. All of these words to me imply having a nice day. They imply having the best day. They also imply being unproductive. Which leads to being, even if only temporarily, nonconsumptive, and this is a crime in America, and more explicitly criminal depending upon any number of quickly apprehended visual cues.”

It’s two more pages. Should I finish it, or should we…

Tippett: It’s great, yeah.

Gay: Finish it?

Tippett: Yeah.

Gay: “For instance, the darker your skin, the more likely you are to be ‘loitering.’ Though a Patagonia jacket could do some work to disrupt that perception.

[laughter]

Gay: “A Patagonia jacket, colorful pants, Tretorn sneakers with short socks, an Ivy League ball cap, and a thick book not the Bible and you’re almost golden. Almost. (There is a Venn diagram someone might design, several of them, that will make visual our constant internal negotiation toward safety, and like the best comedy it will make us laugh hard before saying Lord.)

“It occurs to me that laughter and loitering are kissing cousins, as both bespeak an interruption of production and consumption. And it’s probably for this reason that I have been among groups of nonwhite people laughing hard who have been shushed — in a Qdoba in Bloomington, in a bar in Fishtown, in the Harvard Club at Harvard. The shushing, perhaps, reminds how threatening to the order are our bodies in nonproductive, nonconsumptive delight. The moment of laughter not only makes consumption impossible (you might choke)…

[laughter]

Gay: “…but if the laugh is hard enough, if the talk is just right, food or drink might fly from your mouth, if not, and this hurts, your nose. And if your body is supposed to be one of the consumables, if it has been, if it is, one of the consumables around which so many ideas of production and consumption have been structured in this country, well, there you go.

“There is a Carrie Mae Weems photograph of a woman in what looks to be some kind of textile factory, with an angel embroidered to the left breast of her shirt, where her heart resides. The woman, like the angel, has her arms splayed wide almost in ecstasy, as though to embrace everything, so in the midst of her glee is she. Every time I see that photo, after I smile and have a genuine bodily opening on account of witnessing this delight, which is a moment of black delight, I look behind her for the boss. Uh-oh, I think. You’re in a moment of nonproductive delight. Heads up!

[laughter]

“Which points to another of the synonyms for loitering, which I almost wrote as delight: taking one’s time. For while the previous list of synonyms allude to time, taking one’s time makes it kind of plain, for the crime of loitering, the idea of it, is about ownership of one’s own time, which must be, sometimes, wrested from the assumed owners of it, who are not you, back to the rightful, who is. And while having interpolated the policing of delight such that I am on the lookout for the overseer even in photos I have studied hundreds of times, on the lookout always for the policer of delight, my work is studying this kind of glee, being on the lookout for it, and aspiring to it, floating away from the factory, as she seems to be.”

[applause]

[music: “Kid Kodi” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I wanted to talk to you about justice and how you grapple with that reality, that aspiration, that concept. And there has been an evolution of that. You have brought together the idea of longing for justice and working for justice with also exalting the beautiful and tending to what one loves, as much as what one must fight.

Gay: Tending to what one loves feels like the crux. Yeah, I’m very confused about justice, I think. I feel like the way we think of justice is absolutely inadequate, often. Often. Not everyone. I am curious about a notion of justice that is in the process of exalting what it loves.

Tippett: So here’s something you wrote somewhere. You said, “I often think the gap in our speaking about and for justice, or working for justice, is that we forget to advocate for what we love, for what we find beautiful and necessary. We are good at fighting, but imagining, and holding in one’s imagination what is wonderful and to be adored and preserved and exalted is harder for us, it seems.”

Gay: I think so. I think so. I even think of — I’m a teacher. And we have these things called “grades.”

[laughter]

And for the most part, I think of grading, and much of what we do, as an expression of a kind of punitive mentality.

Tippett: Like “Was it good enough?”

Gay: Or even, ‘You didn’t do this, so.” And that feels so not what I’m interested in doing. And I think about how deeply it is in my bones to think about, because I’m that professor who, I really want to give everyone A’s. And maybe, from here on out, everyone will get As. Take my class.

[laughter]

But there is this way, still, that I think, “Well, what if this person didn’t do that? What if that person doesn’t do that exercise?” Or “What if that person” whatever? You know. It’s not a thing of — it’s not love, when I say, “Well, I’ll dock them.” It’s punishment. And it’s also cultivating, among the other people in that class, a sense of being potentially punished. And that is just such not a way that I want to teach, you know?

Tippett: And it’s not to deny what is wrong…

Gay: No.

Tippett: …but it’s to frame that in terms of the place we want to be, the fullness of that, and the small ways we maybe move towards it on any given day, in any given paper, in any given interaction.

Gay: Totally. How do we correct a thing, with love?

Tippett: I think about journalism a lot and how — when you talk about the delight — you developed a delight radar and a delight muscle — basically, journalism has a despair radar and a despair muscle.

Gay: I know. I know.

Tippett: And there’s nothing — it’s not that we don’t need to know those things. It’s not that those aren’t part of the story. But I feel like what you’re saying is — that’s what you mean, right? It’s inadequate.

Gay: Well, part of the story, that’s the thing. If the news was as invested in talking about how this person was great to that person as it was in talking about how that person was terrible to that person, it would be a radically different experience. It would be like, “Oh, okay — we live amongst people. People do many things.”

[laughter]

But it feels — part of what I think is interesting about this book is that it brings to my attention, just clear, that many things are happening. Many things are happening. And like you said — it sells. It sells.

Tippett: Well, it also — our brains are wired to get riveted by something that’s scary, that’s threatening. We mobilize around that. It’s automatic.

But I also think that the exercise of the book is to say, “Look how amazing this is.”

Gay: Yeah, totally. And I also think that —

Tippett: “And look how intricate it is.”

Gay: And intricate, and endless, and unbelievable. And I also think that there’s a part of our bodies that are wired — and this is a thing that I noticed, that when I would experience something delightful, and sometimes I’d be like, “Oh, that’s wonderful” — so often, I’d be like, “I want to tell you.” It is this thing that actually makes me reach out towards someone.

And that feels bodily. That feels — I don’t know if a scientist has found this out yet, but when something good happens, do we gather around a thing? But i it is a feeling that I have, a deep feeling that I have, and I feel like it’s something that I witness, too — that people kind of want to share the stuff that they love.

Tippett: And what you do is, you put vivid language to it; you put beautiful, riveting words to it. So there’s a little bit of discipline involved. But that shifts it, too, to being more interesting.

Gay: How do you mean?

Tippett: Well, I mean that if we acknowledge this reality that on autopilot, we’re going to be galvanized by something terrible coming at us, then those of us who care about getting this other story about ourselves in the world out there have to also apply some intelligence to doing that well so that it will also rivet. And that’s what I feel like this book did that. It was an intentionality. It was a practice. And it’s with this care with words and stories, which we do respond to.

Gay: And I think it also knows, or comes to know that what is galvanizing, as well, is what we love, and has a kind of belief in that. And also believes in the thing — the book itself believes that it’s elbowing its neighbor and being like, “Right? Look at all this. What do you love? What do you love?”

Tippett: Yeah. There’s this line, this famous line from Cornel West, that justice is love made public, which I think has wisdom in it, and I also don’t think it’s a big enough statement. And I feel like you put — in your writing, in your other writing and your other work, like The Tenderness Project — I feel like what you’re trying to do with that is — So let’s give some complexity and some texture to what love made public is, and how it works. And just that simple word, “justice,” doesn’t do it.

So The Tenderness Project. Talk about that.

Gay: My friend Shayla and I were talking about just what might be a nice project to do these days, and so we decided to start this thing, called The Tenderness Project. And it’s — every ten days or so, someone will release a “tenderness,” we call them. And they can be like be a little essay, or —

Tippett: Tendernesses.

Gay: Tendernesses. And it can be an essay or a poem or a little film or something. But it’s just small — I get a lot of emails that are not, “Here’s a tenderness.” A lot of them are like, “Watch out!” And when you see one that says, “Here’s a tenderness,” it’s like, oh, wow. That’s okay.

Tippett: And that’s also just such a good example of — because we are riveted by this idea — I think everybody in this room — just, “Oh, yeah, tenderness. Tendernesses.” But it’s a softer place in us.

Gay: It’s many things, that’s the thing, too. Tenderness, it is a softer place in us —

Tippett: I mean the part of us that gets interested in it.

Gay: Totally, exactly. Right. And sometimes we’re probably skeptical of it; and we defend against it in ourselves and others, for sure. But I love the word “tender” because it implies the softness, I would say, the vulnerability. It also implies “one who tends.” It also is an exchange. So “tender” is many things. To be tender, to be engaged in tenderness, is many things.

And those things are — they also imply, I think, an other. They imply, if you’re tender, there are other things. There are other people or other —

Tippett: I also feel like I think almost anybody would have — I think there are memories in my body. So, when the language of tenderness comes up — it is transformative. It’s one of those ordinary, transformative experiences.

Gay: The experience of tenderness.

Tippett: Of either receiving it or showing it.

Gay: Yeah. I often think, when I think of tenderness, I think of my father. We had years we didn’t get along at all. But he could not not-put his hand in my hair and move my head around. And I just — we mostly didn’t talk, for a while, but he couldn’t not touch me. And that’s — and then, we could go on and on and on and on and on and on with that.

Tippett: You also wrote — I also want to note that you also write a lot about football. And you played football.

Gay: [laughs] I did.

Tippett: And so you think about tenderness very much in touch with a culture of violence that we also live with and that’s strangely intertwined with fun and joy and love and all these beautiful things.

Gay: Yeah, I played college football. I got a scholarship because I could hurt people.

[laughter]

Basically, that’s what it is. Some of these people are like, “Well, aren’t you skilled at the game?” No. I mean, yeah, but because I could hurt people. That’s what it is.

And in the midst of that, as well, in addition to all kinds of brutality and stupidity, is all this tenderness. That, in fact — some of the tenderness I think of is having my right MCL blown out by a good chop block from someone, and my buddy Glenn like running — running! — to pick me up. So you’re right, it’s very much entwined, probably, in the way I’ve been thinking about it for most of my life, because for most of my life I’ve been deeply engaged in thinking about sport and the violence in sport. I’ve been in sport, or I’ve been thinking about sport and the many things that sport is.

[music: “Orchard Lime” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: We want to hear some more of you. But just before that, also, you did write this — I think more on this theme, justice is love made public, but more contour to “love made public.” And you’ve also been writing about mercy. You wrote this beautiful piece in The Sun. I just want to spend a couple minutes on this. It was so striking to me — back to your garden — because it starts with you, doing potatoes and chard and garlic, and your back seizes up. And you realize, eventually, that that has to do with an experience that you had; that your body is taking in this experience you had with the police the night before.

But where you go with mercy, like with tenderness, is that it may be the only — that we have to say everything that needs to be said and reveal everything that needs to be revealed, and then make this other move, which again is that beyond of mere justice. I don’t know. How would you…

Gay: Say it again. Would you? Would you ask it again?

Tippett: Well, where could — I’m sure somebody’s asked you this. It’s like “How can you use a word like joy right now?” How can you use a word like “mercy” right now? Being a Black man and doing nothing wrong and having to constantly think about what’s going to happen when you see a policeman, for example.

Gay: Yeah. I don’t know, you know; that piece remains a puzzle to me. And what’s interesting to me about that essay is that there aren’t answers. There’s a fundamental question, which is, we ought to know each other better.

Tippett: Yes, but that’s a different move. There’s no answer, but there’s a move. I mean, here’s a little piece of it: “What if we honestly assessed what we have come to believe about ourselves and each other, and how those beliefs shape our lives? And what if we did it with generosity and forgiveness? What if we did it with mercy?” And you’re talking about really hard, inexcusable things in our history and our present.

And you wrote, “The corrupt imagination might become visible. Inequalities might become visible. Violence might become visible. Terror might become visible. And the things we’ve been doing to each other, despite the fact that we don’t want to do such things to each other, might become visible. If we don’t, we will all remain phantoms — and, as it turns out, it’s hard for phantoms to care for one another, let alone love one another.”

Gay: Yeah, that’s what I was trying to say. [laughs]

[laughter]

[applause]

That’s it.

Tippett: Yeah.

Tippett: Is there a poem or a piece from Book of Delights that occurs to you that you’d like to read right now?

Gay: The funny thing about this is that when I was writing this, I’d always be like — any friend I could get, I’d snag them and I’d be like, “Oh, can I read you a delight?” So anytime I have the opportunity, I do it. But one that maybe connects to what you were just saying? Is that what you’re saying?

Tippett: Or that you just feel like reading.

Gay: I just feel like reading this one. It just showed up. [laughs] It’s called “Name: Kayte Young; Phone number: 555-867-5309.”

[laughter]

Kayte wanted me to put her real phone number in there, but the editors were like, “Nope.”

Tippett: I did wonder about that when I first saw it.

Gay: You did? You know the song?

Tippett: Yeah, yeah.

Gay: Okay, good.

Tippett: I wondered.

Gay: “Today I was sitting down to a meeting with my friends Dave and Kayte, to discuss the excerpt of Kayte’s graphic novel our little press is going to publish. When Kayte pulled the box from her bag that contains all her beautifully drawn pages, her beautiful cargo, which she’s calling Eleven, I noticed a tag on the interior of her backpack with a space for a name and phone number. There might also have been an ‘If you find this, please return to.’ And Kate had filled it out.

“The last person — the last adult — I knew to fill that space out was Don Belton, whose every journal, it seemed, had his name and phone number, or name and address, along with the admonition, ‘DO NOT READ THIS,’ which strikes me as an invitation, if not a command, to read this.

[laughter]

“Though I had known Don, and so respected his wishes from this, the other side, as we boxed up those hundreds of journals and pictures and correspondences and mementos and took them to what would become his archive at the Lilly Library. There was something literary, and also of another era, in Don’s naming and addressing or naming and phone numbering all of his journals, which makes sense to me, for Don also sometimes seemed to be of another era. One time, when the children in his class were going on about Li’l So-and-so coming to perform for Senior Week or whatever they call it here, Don said, probably with a very straight face, When I was in college, Duke Ellington played. Do you know who that is?

[laughter]

“Not to mention, Don was an E. M. Forster man.

“But Kayte’s naming and phone-numbering her bag, which truly filled my heart with flamingos, or turned my heart into a flamingo, strikes me as a simple act of faith in the common decency, which is often rewarded but is called faith because not always. Like the time when I was delivering papers in the predawn, cutting paths through the dew-wet grass in between the apartments, and I found, on the sidewalk, a wallet with five hundred dollars in it. There was plenty of identifying material in the wallet—not a license or credit card, but other things all with the same name on them. When I found that one of those things was something like a frequent-gamblers card, issued by one of the Atlantic City casinos, I decided this was dirty money and I might as well get some.

[laughter]

“I’m sure I would’ve figured out how that money belonged to me even if I found evidence in the wallet that the owner was a frequent donor to Oxfam or Amnesty International, I needed that new Steve Caballero mini” — that’s a skateboard — “and about four hundred twenty dollars’ worth of gummy bears.

[laughter]

“But he wouldn’t, I wouldn’t, keep that money today. Maybe in part because I can afford my own gummy bears, but even more so, I think, because I now believe in the common decency, and I believe adamantly in faith in the common decency, which grows, it turns out, with belief, which grows, it turns out, with faith, and on and on, as evidenced by ‘Name: Kayte Young; Phone number: 555-867-5309.’”

[laughter]

[applause]

Tippett: I often ask the question about — of somebody at the end of an interview — what’s making you despair today, and where are you finding hope? And I don’t want to ask you about despair. What is giving you delight, today? Is there any little thing, think of something small or large — what comes to mind?

Gay: The way these lights are working is pretty amazing, some of the reflections up there. There was someone up here who had a very precise, beautiful laugh that was — You know, that’s kind of nice, just to be in a room with people laughing.

There was a couch in the room back there, in the not quite the changing room, but it’s a very nice-looking couch, I thought. I had a nice little rest before I came over here, over at the Green Room, I guess they call that. Those were all delightful things.

Tippett: Have you done kettlebells today?

Gay: [laughs] I was hoping you were going to ask. I didn’t know if that was off-limits.

Tippett: This is something we have in common. Can’t talk about it; we don’t have time. But that would be a delight. [laughs]

Gay: I did not do kettlebells today, but I will, probably, tomorrow.

Tippett: It’s all good.

Would you read just from here on page 49, and just to the end of that? This is from The Book of Delights.

Gay: “Among the most beautiful things I’ve ever heard anyone say came from my student Bethany, talking about her pedagogical aspirations or ethos, how she wanted to be as a teacher, and what she wanted her classrooms to be, she said: ‘What if we joined our wildernesses together?’ Sit with that for a minute. That the body, the life, might carry a wilderness, an unexplored territory, and that yours and mine might somewhere, somehow, meet. Might, even, join.

“And what if the wilderness — perhaps the densest wild in there — thickets, bogs, swamps, uncrossable ravines and rivers (have I made the metaphor clear?) — is our sorrow? Or, to use Smith’s term, the ‘intolerable.’ It astonishes me sometimes — no, often — how every person I get to know — everyone, regardless of everything, by which I mean everything — lives with some profound personal sorrow. Brother addicted. Mother murdered. Dad died in surgery. Rejected by their family. Cancer came back. Evicted. Fetus not okay. Everyone, regardless, always, of everything. Not to mention the existential sorrow we all might be afflicted with, which is that we, and what we love, will soon be annihilated. Which sounds more dramatic than it might. Let me just say dead. Is this, sorrow, of which our impending being no more might be the foundation, the great wilderness?

“Is sorrow the true wild?

“And if it is — and if we join them — your wild to mine — what’s that?

“For joining, too, is a kind of annihilation.

“What if we joined our sorrows, I’m saying.

“I’m saying: What if that is joy?”

[applause]

Tippett: Ross Gay, thank you.

Gay: Thank you.

[applause]

[music: “Eventide” by Gautam Srikishan]

Tippett: Ross Gay lives in Bloomington Indiana, where he’s a professor of English at Indiana University. His books include The Book of Delights, Inciting Joy, and the poetry collection Be Holding.

[music: “Eventide” by Gautam Srikishan]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Eddie Gonzalez, Lucas Johnson, Zack Rose, Julie Siple, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Gautam Srikishan, Cameron Mussar, Kayla Edwards, Tiffany Champion, Andrea Prevost, and Carla Zanoni.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. We are located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. Our closing music was composed by Gautam Srikishan. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

Our funding partners include:

The Hearthland Foundation. Helping to build a more just, equitable and connected America—one creative act at a time.

The Fetzer Institute, supporting a movement of organizations that are applying spiritual solutions to society’s toughest problems. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, Dedicated to cultivating the connections between ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting initiatives and organizations that uphold sacred relationships with the living Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

And, the Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.