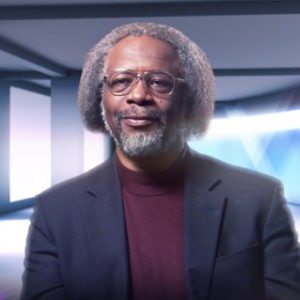

S. James Gates and Thomas Levenson

Einstein's Ethics

Part one of this series takes Einstein’s science as a starting point for exploring the great physicist’s perspective on ideas such as mystery, eternity, and the mind of God.

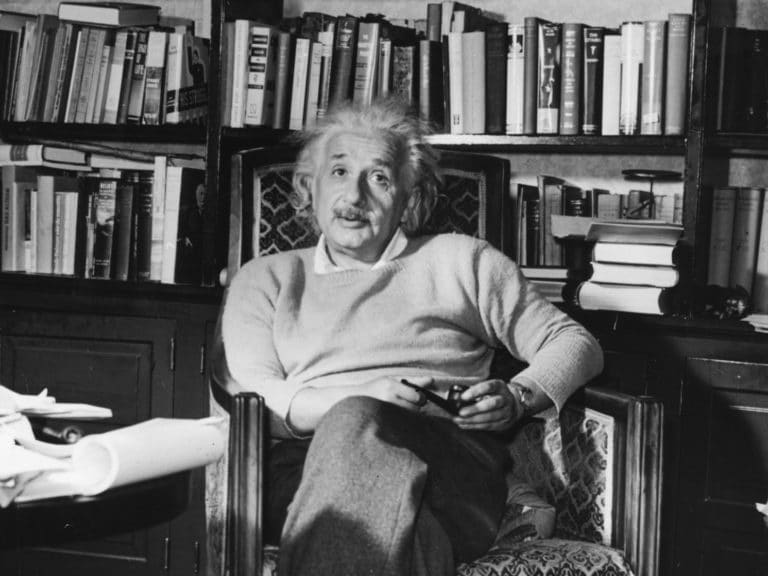

Image by Lucien Aigner / Stringer/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

Thomas Levenson is Associate Professor of Science Writing at MIT. He's produced "Einstein Revealed" for NOVA and has authored several books on science and technology, including Einstein in Berlin.

S. James Gates Jr. is Toll Professor of Physics and Director of the Center for String and Particle Theory at the University of Maryland in College Park. He serves on President Obama's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology.

Transcript

March 15, 2007

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Einstein’s Ethics.” We’ll explore the forgotten humanitarian passions of the great physicist Albert Einstein. We’ll probe the fascinating relationship between his scientific imagination and his views on war, race and spiritual genius.

MR. S. JAMES GATES, JR.: Prior to Martin Luther King, I don’t know of any other Nobel Laureate who spoke so forcefully for the rights of African Americans.

MR. TOM LEVENSON: He thought that science had not just a method, you know, a way of thinking about the natural world that would produce rigorous results, he thought science had a social order as well, and one that wasn’t just the accumulation of research and results

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. This hour, the second part of our exploration of the forgotten spiritual and ethical legacy of Albert Einstein. Einstein is famous for his discoveries about space and time that changed the way we see the world. But he was also famous in his day for humanitarian passions that interacted in intriguing ways with his scientific imagination. Technology in his generation, Einstein once said, was like a razor blade in the hands of a three-year-old. And he called the saints and spiritual leaders of the ages geniuses “in the art of living,” more necessary to the dignity of humanity than the discoverers of objective truth.

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics and ideas.

Today, “Einstein’s Ethics.” Albert Einstein could scarcely have been born a Jew in Germany in 1879 in a more threatening age. His lifetime would span two world wars and the Holocaust. He did not perform well in the regimented Prussian schools of his childhood, however, and he finished his education in Switzerland. As a young man, he took advantage of the relative freedom of an obscure job in the Swiss patent office and made his mark on science. He burst into the public eye, in 1905, with a series of discoveries. His theory of special relativity linked space, time, matter, energy, and light. A decade later he accounted for the effects of gravity in his theory of general relativity, which his fellow physicists call as much a work of art as of science.

The popular image of Einstein that we still know today is at once erudite and comical — “a Charlie Chaplin face,” one British journalist wrote, “with the brow of Shakespeare.” It was a face that cameras loved. And Einstein used that appeal towards more than his own fame. In his person, he revitalized the moral stature of science itself. The carnage of World War I had been wrought in part by chemists. As Einstein himself often said, scientific knowledge that should have improved human life was repeatedly marshaled towards weaponry and destruction. In 1945, as the modern age commenced with the end of World War II, Einstein repeated this concern.

MR. ALBERT EINSTEIN: The war is won, but the peace is not. We cannot and should not slacken in our effort to make the nations of the world, and especially their governments, aware of the unspeakable disaster they are certain to provoke unless they change their attitude towards each other and towards the task of shaping the future.

MS. TIPPETT: This hour we’ll trace the development of Einstein’s public ethics, which emerged in the tumult of early 20th-century Germany. One by one, his most esteemed scientific colleagues threw themselves behind warmongering nationalism and, later, fascism. My first guest, Tom Levenson, is the author of a biography of Einstein and his times, Einstein in Berlin.

MR. LEVENSON: His initial opposition to what was happening around him was not pacifism in the way that he became a true ethical pacifist in the ’20s. It was a kind of internationalism based on what he imagined the proper life of the scientist was about. He saw science and the scientific community as a transnational kind of super nation of good, well-thinking, moral individuals. And he came to Berlin just before the First World War; he came in part because, even though he felt no particular attraction to Germany, some of the minds that he most wanted to spend time with were clustered right there in Berlin, great physicists and others. And he thought that they thought as he did, that their allegiance to science was more important, their allegiance to truth, their allegiance to seeking truth and sharing it.

MS. TIPPETT: And it seems to me that part of his initial response, and you just alluded to this, is just that he’s so upset about this collapse of reason.

MR. LEVENSON: I think Einstein’s reaction to the sort of rabid nationalism of even those close to him in 1914 is partly a response to what he sees as the collapse of reason. But it’s not just the collapse of reason in the sense of people not thinking clearly, it’s more like the collapse of what he thought was a moral order. He thought that science had not just a method, you know, a way of thinking about the natural world that would produce rigorous results, he thought science had a social order as well, and one that wasn’t just the accumulation of research and results. And that was what was shattered in the first years of the war, and that was what made him, I think, really start to think as an ethical person what ought one to do. It’s not enough just to do something that seems to be a value, like science, you actually have to take a positive responsibility for your own action. And that’s when he starts thinking like somebody who wants to be involved in ethics. You know, more than just saying, “Oh, people are crazy, people are stupid, people are unreasoning.” You know, that’s obviously something he did think in the context of the war, but that wasn’t enough.

MS. TIPPETT: In 1915, the same year that Einstein published his groundbreaking theory of general relativity, he also published an essay directed at the German public titled “My Opinion of the War.” World War I had begun the previous year. Einstein compared warring nations to little boys in a schoolyard. Here is an excerpt.

READER: I will never forget the sincere hatred my schoolmates felt for the first graders of a school in the neighboring street. Innumerable fistfights occurred with many a hole in the head the result. Understandably, the more modern organized states had to push these manifestations of primitive virile characteristics vigorously into the background. But wherever two nation states are next to each other and without a joint super power above them, those feelings at times generate tensions that lead to catastrophes of war. Every well-meaning person should work hard on himself and in his personal circle to improve in these respects. But why so many words when I can say it in one sentence, and in a sentence very appropriate for a Jew: Honor your master Jesus Christ, not only in words and songs, but rather foremost in your deeds.

MR. LEVENSON: We have this image of the kindly grandfather, but Einstein was a very sharp wit. He could be harsh in his language, and he didn’t tolerate foolishness or hypocrisy gladly. So that almost dismissive slap, you know, “Honor Jesus Christ. And I have nothing more to say about it. I’m just a Jew quietly standing to one side observing your hypocrisy,” is part of what’s being said there. Partly, he’s absolutely sincere. The universal message of Jesus, the one that speaks beyond the specifics of Christian doctrine or ritual or what have you is that one of honoring humankind, all humankind. And Einstein certainly did feel that very strongly. So the sarcasm is there, and so is the message. And I think the reference to his own Jewishness is not actually that surprising at this point. It’s earlier than his full-fledged engagement in Jewish causes, but, you know, he’d been aware of anti-Semitism, he’d been aware of himself as a Jew in the negative sense, as somebody seen as “the other” by the larger Christian society around him for a long, long time. And the experience of moving to Berlin and experiencing some of the sort of genteel anti-Semitism that was present in Berlin even before the rise of the really hateful anti-Semitism of the post-war period, you know, I mean, I think he had a sense of himself as a Jew, even though it wasn’t the same sense he would have later when he got more deeply engaged affirmatively in the Berlin Jewish community.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, there’s another quote from 1918 where he again refers to Jesus and to himself as a Jew, “I prefer to string along with my countryman, Jesus Christ, whose doctrines you and your kind,” he’s writing to a German nationalist, “consider to be obsolete. Suffering is indeed more acceptable to me than resorting to violence.” What I have read and heard is that he never gave himself over to Jewish devotion in any kind of sense or worship. You know, he did have this sense of the moral core of Judaism, “the fanatical love of justice,” as he said it, or a moral attitude in life. I mean, he also concluded for himself that Judaism was not a transcendental religion.

MR. LEVENSON: It’s always dangerous to put words in anyone’s mouth, but I think what he meant by Judaism not being a transcendental religion is what a lot of people have understood by that thought, which is there is a transcendent spiritual strand in Judaism. There’s no question about it. But a great deal of Judaism, the preponderance of sort of Judaism as I understand it and I think as Einstein understood it, is really about this world, how to live in this world, how to do justice in this world, how to be charitable in this world, how to be honorable in this world, what’s required of you to be a good person. I mean, the classic phrase in Hebrew of the obligation of the Jew is tikkun olam, “to heal the world.” And that’s this world, not a transcendent one.

MS. TIPPETT: Now, he did become openly Zionist and a great champion of the state of Israel later in his life, and I just want to ask you how he reconciled that given his strong objection to the emotionalism of nationalism, you know, not just in Germany but all over Europe in the earlier part of the 20th century. Did he see that as qualitatively different, sort of being passionate about the Jewish state?

MR. LEVENSON: He actually became committed to the Zionist cause quite early. I mean, he was recruited to go to the United States to raise money for the founding of Hebrew University by the Zionist movement in 1921, you know? But he wrote letters. I mean, he wrote about how troubling it was that the reality of Jewish life as the situation got worse and worse in Europe, you know, sort of required a national solution, and he only hoped that the necessary relative weakness of a small Jewish state in the middle of the Middle East would keep the nationalism of that state in check, would keep it modest. He was aware of the probability of conflict with the Arabs. He hoped that there would be solutions; he wrote about them. And critically, even though he supported the Zionist goal, he was never officially a Zionist, and it was a distinction that mattered. I mean, when he was offered the presidency of Israel after Weizmann’s death, you know, Ben-Gurion, the great founding prime minister of Israel, who made the offer…

MS. TIPPETT: That was in 1952.

MR. LEVENSON: Right. Says, “Oh, my God, what do we do if he accepts?” And Einstein said no, and he said no officially because he was too old, and he didn’t want to move from Princeton and all that. But he really said no — and he admitted this — because he didn’t want to be in a position where he would have to disagree publicly with the leadership of the new state of Israel, and he felt sure it would happen.

MS. TIPPETT: In the letter in which he officially declined, I mean I was quite struck by this sentence, though — this is in 1952, not that long before his death — he wrote, “My relationship to the Jewish people has become my strongest human bond ever since I became fully aware of our precarious situation among the nations of the world.”

MR. LEVENSON: For Albert Einstein, he always knew the Nazi movement was a deadly, life-destroying disaster for Germany and for the world. But when the true extent of the Holocaust and the sort of rabid, uncontrolled, utterly heartless and ruthless destruction of human lives and a human culture that he saw as having enormous value, you know, here transcendent value, he never got over that. It sealed, I think, a number of both emotions and conclusions that he had reached. And I believe at that point, you know, his identification with Judaism, you know, became as total as he said it was. You know, it becomes more important to stand by something that’s been so nearly destroyed.

MS. TIPPETT: Einstein biographer Tom Levenson. I’m Krista Tippett and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, we’re exploring the ethical sensibility and humanitarian activities of the great physicist Albert Einstein.

There was a contrast between Einstein’s public humanity and his ethical conduct in private relationships. At a young age, he married a fellow physics student, Mileva Maric, with whom he had two sons. He was a fairly remote figure for most of his sons’ lives. Before they were married, Mileva also gave birth to a daughter whom Einstein never met. Her fate was lost to history. Mileva never received the credit some believe she deserved for collaborating on his early discoveries. Einstein once wrote of her to his cousin Elsa, whom he later married, “I treat my wife as an employee I cannot fire.” Einstein acknowledged this disparity in his character. “My passionate sense of social justice and social responsibility,” he wrote, “has always contrasted oddly with my pronounced freedom from the need for direct contact with other human beings.” Again, Einstein biographer Tom Levenson.

MR. LEVENSON: Einstein was fully as complex and real a human being as any of the rest of us are. And in certain of his relationships, he was deeply flawed. I mean, he really hurt many of the people closest to him. The temptation with a great figure like Einstein or anyone else is always to try and see them as unalloyed greatness, some kind of pure essence of something the rest of us are not. But, in fact, he has greatness in many ways. He’s a great scientist. He took the fame that was sort of thrust on him, and he, with courage and, I think, a real ethical sensibility, tried to make use of it for the betterment of the world. You know, across the ’20s and throughout his life, if there was a specific problem that caught his attention, he’d intervene. He tried to intervene in the case of union organizers who were unjustly jailed in California. He tried to help with disastrous individual cases in the Balkans. He wrote to the British when they were going to hang a bunch of Arab protesters in the Palestine Mandate, and he was one of a group of people who helped get most of those, two dozen or so, death sentences revoked.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. I mean, it is very impressive. He intervened on behalf of individual prisoners, as you said, around the world, people in Czechoslovakia, in Bulgaria. So, I mean, tell me what was behind all of that activity in terms of how Einstein saw — I don’t know — some of these big concepts like, you know, right and justice.

MR. LEVENSON: Certainly he was an internationalist. I think he saw that he himself had standing in any dispute. What’s the John Donne line? “If you damage any individual, you damage me” kind of thing. I think he had that sensibility.

MS. TIPPETT: He really internalized that.

MR. LEVENSON: And the cases he mostly intervened in, and not exclusively, but a lot, were cases involved in causes in which he’d already been a public figure. So I think he felt some sort of direct responsibility, not just a sort of “every man is my brother” kind of feeling. He intervened in a lot of draft resister cases, and I think he felt an obligation to do so because, you know, he urged draft resistance. So some people might have done things based on his suggestion, and if they got in trouble, then he had some obligation to them. I think he felt that.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, but I still think it’s amazing that given who he was and how full his life was that he still had an attention span for those kinds of details.

MR. LEVENSON: He had an attention span; he had that. He also had a really good personal secretary in Helen Dukas, who I think shouldn’t be forgotten. But I think Einstein really did have a very strong sense of justice. And, you know, when you say that it doesn’t mean that you just think things ought to be just or things ought to be fair, I think it meant for Einstein and it means practically for anyone who thinks in this way, justice only becomes justice if it’s justice enacted in a specific instance. It’s a fine thing to say, “I believe in the rule of law” and this, that and the other thing. There’s been some very good work recently and a book out on Einstein and race, and one of the things it points out is that Einstein was really progressive. He did more in this country at a time when it really wasn’t an up-front, popular issue to emphasize the need for racial equity, racial justice. I think, again, that was a sense, you know, it’s one thing to say that you believe in, you know, all humankind is to be treated equally and fairly or what have you, and it’s another thing to, you know — it only becomes meaningful if when you confront an obvious inequity, an obvious inference, an injustice, that you put some energy into at least recognizing it, bringing it to the public eye, doing something about it. And Einstein understood that. He did it.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, war is something that preoccupied him to the end of his life, and he lived through many different forms of war, and — what was it? — the last public act of his life was to add his name to a manifesto drafted by Bertrand Russell that called for global nuclear disarmament. As you, having been steeped in his thoughts on wars and military violence, are there ideas that Einstein had about that, or an approach that informs the way you think about these things in our time?

MR. LEVENSON: Yes and no. Einstein’s response to war and to militarism is complicated. It didn’t start out as pure pacifism and it didn’t end as pure pacifism. He became a real, committed, ethical pacifist in the Bertrand Russell style in the ’20s. When Hitler came to power, though, he recognized in Hitler a crisis that could not be resolved by good wishes, by moral persuasion, by hoping for the best. And he recognized, and he told this to Winston Churchill as early as 1933, that Hitler was somebody who needed to be opposed by force. And then, of course, he signed the letters to Roosevelt about pursuing atomic research because of the fears that Germany might develop atomic bombs. And, you know, after the war when the bombs were dropped, he was deeply upset, and he felt that the technological change in the killing power of human weapons was such that a whole new attitude towards war had to come into being.

And, you know, I think that my sense of Einstein’s lessons for us today, and lessons for me today, are sort of summed up in the inconclusiveness of his exchange with Sigmund Freud in ’33, in letters that were ultimately published as a little book called Why War? in which they tried to understand why people fight. And they ultimately concluded that it was something basic to human nature, and perhaps eventually both enough technological development that would make people, you know, comfortable and wealthy and it would scare people off the violence of a technologically advanced war, and education, all these things might help change people’s, you know, really fundamental behavior. But neither Freud nor Einstein held out a lot of hope.

READER: To Sigmund Freud. I greatly admire your passion to ascertain the truth. You have shown with irresistible lucidity how inseparably the aggressive and destructive instincts are bound up in the human psyche with those of love and lust for life. At the same time, your convincing arguments make manifest your deep devotion to the great goal of the internal and external liberation of man from the evils of war. This was the profound hope of all those who have been revered as moral and spiritual leaders beyond the limits of their time and country, from Jesus to Goethe to Kant.

MR. LEVENSON: When Einstein first visited the United States, William Carlos Williams, great American poet, wrote a sort of poem in response, a poem of welcome or of praise that he titled “St. Francis Einstein of the Daffodils.” Not necessarily a great poem, but it’s fascinating. But we make a mistake when we make Einstein a saint. You know, his bust is up there on the gate of heroes at Riverside Church in New York. You know, Einstein himself, when he saw that, laughed and said, “I knew I was a Jewish saint, but I didn’t think they’d make me a Christian one.” And Einstein really was a human being, and he was flawed. Some of his causes were maybe a little crazy. You know, who knows? And, you know, certainly he wasn’t a perfect example of moral behavior to every person he ever encountered. And I think, again, that’s a strength when you really think over Einstein. And the problem with saints, and the problem with thinking of Einstein as a saint, is it somehow absolves the rest of us from responsibility to behave well. You know, behaving that courageously, behaving that concentratedly is something that saints do and the rest of us kind of muddle through. Well, Einstein just muddled through a lot. I mean, he muddled through at a higher level than many of us, but he still was muddling through. And I think that’s the lesson I’d take, despite my affection for St. Francis Einstein.

MS. TIPPETT: Tom Levenson is associate professor of science writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Einstein called the saints and spiritual leaders of the ages geniuses in the art of living, more necessary to the dignity, security and joy of humanity than the discoverers of objective truth. He deeply admired his contemporary, India’s Mahatma Gandhi.

DR. EINSTEIN: I believe that Gandhi’s views were the most enlightened of all the political men in our time. We should strive to do things in his spirit, not to use violence in fighting for our cause, but by nonparticipation in anything you believe is evil.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, we’ll explore how Einstein turned his humanitarian vision to the problem of racism after he left Germany for America. With physicist James Gates Jr., we’ll probe the correlation of this concern to the ethics of Einstein’s scientific imagination.

Visit our award-winning Web site, speakingoffaith.org, where you can listen to the first part of this series, “Einstein’s God.” Our companion site features images of Einstein’s hand-written documents and you can hear more of the voice of Albert Einstein himself.

Also, sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter with my journal. Subscribe to our podcast — an iTunes “Best of 2006” selection — for a free download of our weekly program. Our podcast also includes selected audio clips from my new book, titled Speaking of Faith. Listen when you want, where you want. Discover something new at speakingoffaith.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett.

Today we’re exploring the human, ethical and spiritual sensibility of Albert Einstein, whose discoveries in physics changed the way we think about space, time and the universe. In December 1932, on the eve of Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany, Albert Einstein and his second wife, Elsa, departed for America for an extended stay at Cal Tech. The following March, in 1933, Hitler’s Third Reich barred Jews and Communists from teaching in German universities. Jewish scientists became a special target because they defied the logic of the superior Aryan race. From California Einstein declared to the world that he would not return to Germany. “As long as I have any choice in the matter,” he said, “I shall live only in a country where civil liberty, tolerance and the equality of all citizens before the law prevail.” But there was an ironic qualification to Einstein’s moral embrace of his new homeland.

Even before he left Germany, he’d begun a lively and supportive correspondence with American black leaders and organizers, including W.E.B Du Bois, one of the founders of the NAACP. Einstein had joined his name to an international campaign to save the Scottsboro Boys, nine black teenagers from Alabama who were falsely accused of rape and sentenced to death in 1931. After he emigrated, Einstein’s sense of outrage at America’s racial double standard became personal. He spent the last two decades of his life at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton. That township’s deep segregation left Einstein appalled. Together with the legendary black performer and activist Paul Robeson, he founded an anti-lynching initiative that came under the scrutiny of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. Einstein enjoyed a long friendship with Robeson, whose music he also loved.

[Excerpt of Paul Robeson performing]

My next guest, S. James Gates, Jr. is the John S. Toll professor of physics at the University of Maryland. He is the first African American to hold an endowed chair in physics at a major research university in the United States, and he works in the fields of supersymmetry and string theory. These are modern frontiers of a quest Einstein left unfinished. To the end of his life, he longed to find a unified theory to unite all the disciplines of physics, and when I asked Gates to discuss Einstein’s ethics, he begins by reflecting on the imaginative way Einstein approached his science.

DR. GATES: Essentially whenever his great moments of insight occurred, he cast them in the form of parables. So for example the great breakthrough of special relativity, which occurred in 1905, if you listen to him, he’ll tell you that it all began with him wondering what the world would look like if he could ride along on a beam of light. That’s a story. That’s a parable. Here’s someone who looks at the world, asks very simple questions about the world and recognizes in asking the questions that they contain an essentially deep and fundamental fact, one which, curiously enough when he asks, he does not understand. But he knows the question is right.

MS. TIPPETT: Is there kind of an ethic that is reflected in that science?

DR. GATES: I don’t know if there’s an ethic. As I’ve experienced my profession, which is obviously the one in which he achieved so very much, I’ve been struck by the fact that, in many ways, being a theoretical physicist is being like a composer of music. In fact, I think there’s only one essential difference between the two: namely that for musical composers, one’s ability is judged by the nature of the audience, whereas in theoretical physics, it’s the audience of nature that provides the judgment. So if there’s an ethic, it’s an ethic that involves human creativity. It’s an ethic with an absolute commitment to removing falsehoods from our system of belief. Many people often are confused about what is the essential nature of science. And again I’ll paraphrase Einstein. Once he said he wasn’t even sure the phrase “scientific truth” had any meaning, and for someone who’s worked in science, I think I understand what that means because, you see, science is not about truths. What science is about is making our beliefs less false. We don’t claim to know truth in science. What we claim is that we have provided the best humanly possible explanation for what we see in the world around us. That’s what science is all about.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I’d like to talk to you about Einstein and race. This was a huge concern of his. And you grew up, in my understanding, in a racially segregated world. I mean, it was the ’50s and ’60s…

DR. GATES: Absolutely.

MS. TIPPETT: …but it was Orlando, Florida, and it was what he saw and was shocked by once he came to this country that he, having left Nazi Germany, considered to be a place of tolerance and equality of all people. Is this something that you’ve always known about Einstein?

DR. GATES: No, it’s not.

MS. TIPPETT: Or how did you learn about it?

DR. GATES: It’s certainly not. I learned about Einstein’s comments on race in the early ’90s. A friend of mine, who’s also an African-American physicist, and he said, “Do you know what Einstein said about race?” And I said, “No.” And then he directed me to a book called, Out of My Later Years. And in the book there is a short essay which — well, I have it here with me, and if you don’t mind, I can read some of it.

MS. TIPPETT: No, do. Please.

DR. GATES: Einstein says, “In the United States, everyone feels assured of his worth as an individual. No one humbles himself before another person or class. Even the great differences in wealth, the superior power of a few cannot undermine this healthy self-confidence and natural respect for the dignity of one’s fellowman. There is, however, a somber point in the social outlook of Americans. Their sense of equality and human dignity is mainly limited to men of white skins.” And then he goes on to say, “The more I feel American, the more this situation pains me. I can escape a feeling of complicity only by speaking out. Many a sincere person will answer me, ‘Our attitude towards Negroes is the result of unfavorable experiences which we have had living side by side with Negroes in this country. They are not our equals in intelligence, sense of responsibility, or reliability.'” Einstein answers, “I am firmly convinced that whoever believes this suffers from a fatal misconception. Your ancestors dragged these black people from their homes by force, and in the white man’s quest for wealth and an easy life, they were ruthlessly suppressed and exploited, degraded into slavery.”

When I first came across these quotes, I was thunderstruck, to be quite frank with you. I could not have imagined that, A, Einstein would have made such quotes, but we know he did, and we know he attached great importance to them because in a book of what he considered his most important essays, this essay is included. So we know he thought a lot about this. But after I accepted that, you know, he actually said such things, the next puzzle for me was why? Because, you know, prior to Martin Luther King, I don’t know of any other Nobel Laureate who spoke so forcefully for the rights of African Americans.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, and here is this German Jewish…

DR. GATES: So here’s this German Jewish guy.

MS. TIPPETT: …supergenius physicist…

DR. GATES: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: …who’s working out gravity. I know.

DR. GATES: Right. So how in the world does he get there?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. GATES: This is something that puzzled me and has puzzled me for a long time, but, you see, you’ll remember earlier in our conversation, I talked about Einstein as an exceptional scientist working in an exceptional way. And I concentrated on the fact that when he had these fundamental instances of insight, he cast them in the language of parables. So he asked the question, “What if?” When you think of this as sort of the mode in which Einstein explores science, to me it is not such a great leap for him to have asked the question, “What if I was a person of African heritage?” And because he had the capability to ask the “What if?” question, it opened the door to what I think is, perhaps, the deepest marker of humanity, and that’s empathy. That to me allows me to understand how he got there. I’ve been thinking about this for about a decade or so. This is the only thing that makes sense to me so far.

MS. TIPPETT: It’s kind of these scientific virtues of curiosity and creativity transposed to the social sphere, I guess.

DR. GATES: Yes, and after I thought about it, it should not have been a surprise to me that, in some sense, there’s a consistent view of what the mind of Albert Einstein is doing, whether you look at his science or whether you look at his pronunciations in the larger domain of human societies.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, and we can also guess that because he lived as a Jewish scientist as Nazism approached, he had this experience of being a minority, a persecuted minority.

DR. GATES: He was certainly primed to recognize oppression in whatever guise he encountered it. You know, we all know of him as a great scientist, but there’s this very famous quote he made about his scientific work, and someone asked him if it were proven right or wrong, what would it mean. And he said something like, “If I’m right, the Germans will proclaim me a German, and the French will proclaim me a citizen of the world. But if I am wrong, the French will say I’m a German, and the Germans will say I’m a Jew.” So it’s clear that his experiences before coming to the U.S. primed him to be very sensitive to matters of discrimination and our species’ capability of treating each other in such inhumane ways.

MS. TIPPETT: Physicist James Gates Jr.

In failing health in the years before his death in 1955, Einstein declined most invitations to speak at universities, including Harvard. But he did accept an invitation to speak at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania in 1946. This historic black university was chartered in 1854 as the first institution in the world to provide higher education for male youth of African descent. Here’s a reading from the speech Einstein gave there as reprinted in the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper.

READER: The only possibility of preventing war is to prevent the possibility of war. International peace can be achieved only if every individual uses all of his power to exert pressure on the United States to see that it takes the leading part in world government. The United Nations will be effective only if no one neglects his duty in his private environment. If he does neglect it, he is responsible for the death of our children in a future war. My trip to this institution was in behalf of a worthwhile cause. There is a separation of colored people from white people in the United States. That separation is not a disease of colored people. It is a disease of white people. I do not intend to be quiet about it.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “Einstein’s Ethics.”

Now back to my conversation with string theorist S. James Gates Jr.

DR. GATES: I count myself, in some sense, doubly fortunate because, you see, I get to be an inheritor not just of his scientific accomplishment, but I also get to be an inheritor in a very special way with regard to his concern for the unity of mankind. And that’s something that most of my colleagues don’t share, so it’s something that is a very great source of joy in my life.

MS. TIPPETT: I see that you’ve also been doing some work in Africa. I mean one thing that jumped out at me was that you’ve advised the government of South Africa on the use of their national physics infrastructure and economic development. I wonder, I mean this is just speculation, but it seems to me that the way the world has advanced, I mean, just globalization, that interconnectedness is something that’s very much in line with Einstein’s vision.

DR. GATES: Well, it’s not just his vision. One thing that I guess isn’t particularly clear in the public discussion is that science has been globalized for over a century. It is inconceivable to us who do science that we wouldn’t be talking to our colleagues all over the world. The fact that the good ideas that drive science can come from people in diverse cultures and societies is one that I think scientists picked up on pretty quickly because we saw a direct benefit. In fact I’ve made an argument in an essay about why we as scientists, well, certainly — let me put it this way, why I, as a scientist, believe that diversity is an issue of such great importance, and it has little to do with morality. I mean, those are great arguments, but if I think about how science works, I believe that I can see where diversity plays a role in fostering innovation. And if that’s the case, and we want the most robust and the most accomplished science of which our population can create, then it’s got to be a diverse population, because that very diversity is where you get the outlyers asking the question that nobody else comes up with.

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder if Einstein would have come at it that way.

DR. GATES: Well, remember he was also an outsider.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes, he was.

DR. GATES: Right, and so I suspect that he would have been able to — I’m not aware of any particular comments, but I think if we could have pressed him, I suspect that he would have said that somehow being an outsider is not always a bad thing, that the outsider often carries, because of a slightly different viewpoint, the seed for an innovation.

MS. TIPPETT: Physicist James Gates Jr.

In 1937 Einstein thrilled at a performance in Princeton by the great black operatic singer Marian Anderson. When Anderson was denied a room at Princeton’s best “whites only” hotel, Einstein invited her to stay at his home. This is Anderson’s extraordinary voice.

[Excerpt of Marian Anderson performing]

DR. GATES: If I was a musical composer, you could ask me the question, “How does your work composing these great works of music impact upon your sense of humanity and ethics?” And I don’t know if, you know, it would occur to you or someone else to ask a composer such a question, but it certainly could be asked. Well, you see, what we do in physics is not different from that. I think most of us who are scientists live in a condition that most people would find intolerable because one thing that I think is true about people in general is that we abhor uncertainty. I think that a large part of understanding human behavior is an attempt to create certainty, sometimes not always where it actually exists, but we have to have a sense of certainty for security of some level. For those of us who are scientists, however, we come to live knowing that we can never be completely certain.

And this is a state that, if someone ever does an MRI study about this, I have a suspicion that they’ll find uncertainty is actually perceived in the brain as akin to some sort of pain. But those of us who are scientists essentially learn to live with that. So if you ask me the impact that doing science has on my humanity and sense of ethics, I cannot imagine that it has any less of an impact than it would on a composer or a poet or an author or anyone who’s striving to use that part of our mind that we, you know, we call creative to bring some sense of order and harmony to the kind of chaos that we find. So, you know, one is humbled by it. One is — and I’ve quoted Einstein on these things and his sense of mystery. I think those of us who work in these areas come away with a deep sense of mystery and a deep sense of our own humanity. Perhaps different from that which most people experience, but I don’t think it’s any less human. I don’t think it’s any less part of the human story nor the human condition.

MS. TIPPETT: S. James Gates Jr. is the John S. Toll professor of physics at the University of Maryland.

Musical evenings with friends were a rare social joy for Einstein. On such occasions, he always insisted on playing Haydn. “Haydn,” he said, “was a musical genius who could write a symphony in the afternoon and we are still playing it.” Einstein’s art of science also remains with us, and his humanitarian vision, too, remains relevant to our time on many levels. In closing, here are the words of Einstein as the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded in 1945 as the post-World War II modern era commenced.

DR. EINSTEIN: “The world was promised freedom from fear, but, in fact, fear has increased tremendously since the termination of the war. The world was promised freedom from want, but large parts of the world are faced with starvation while others are living in abundance. As far as we, the physicists, are concerned, we are no politicians. But we know a few things that the politicians do not know: that there is no escape into easy comfort, there is no distance ahead for proceeding little by little and delaying the necessary changes into an indefinite future. The situation calls for a courageous effort, for a radical change in our whole attitude in the entire political content.”

MS. TIPPETT: Contact us online at speakingoffaith.org. Listen to the first part of this series, “Einstein’s God.” Let us know what you think. And hear more of S. James Gates, Jr. and why he believes being a physicist is like playing music on a planet with no sound.

Also, subscribe to our e-mail newsletter and our podcast, and never miss another program again. Our podcast is a free download of each week’s program that now includes excerpts from my new book, Speaking of Faith. Listen when you want, wherever you want. Discover something new at speakingoffaith.org.

Special thanks this week to Steven Epp and the Theatre de la Jeune Lune, the Albert Einstein Archives at Hebrew University in Jerusalem and Princeton University, Gustavus Adolphus College, and to Fred Jerome and Rodger Taylor for their work Einstein on Race and Racism.

The senior producer of Speaking of Faith is Mitch Hanley, with producers Colleen Scheck and Jody Abramson. Our online editor is Trent Gilliss. Bill Buzenburg is a consulting editor. Kate Moos is the managing producer of Speaking of Faith. And I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.