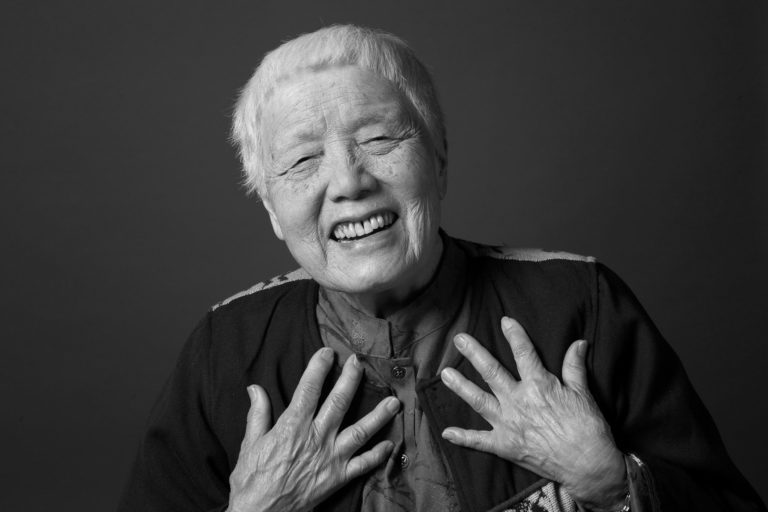

Sister Joan Chittister

Obedience and Action

In over 50 years as a Benedictine nun, Sister Joan Chittister has emerged as a powerful and uncomfortable voice in Roman Catholicism and in global politics. If women were ordained in the Catholic Church in our lifetime, some say, Joan Chittister would be the first female bishop.

Image by Alex Wong/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Joan Chittister is a sister of Mount St. Benedict's Monastery in Erie, Pennsylvania. She serves as co-chair of the Global Peace Initiative of Women. She is a columnist for the National Catholic Reporter and Beliefnet and a best-selling author of more than 30 books.

Transcript

October 4, 2007

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Obedience and Action,” a conversation about religion and the world with Sister Joan Chittister. If women were ordained in the Catholic Church in our lifetime, some say, Joan Chittister would be the first woman bishop.

SISTER JOAN CHITTISTER: The church is a human institution, and it is slow. It’s also a universal institution. It takes a long time for ideas to seep to the top, let alone to move the bottom. So you just realize that what is going on right now is simply the seeding of the question. It comes down to how many snowflakes does it take to break a branch? I don’t know, but I want to be there to do my part if I’m a snowflake.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

I’m Krista Tippett. Sister Joan Chittister is a powerful woman of our time, a venerable and uncomfortable voice in her beloved Catholic Church. We’ll speak this hour about her life in a 1500-year-old monastic tradition and how that has shaped her into a global forward-thinking activist in our time.

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics and ideas. Today, “Obedience and Action,” a conversation with Sister Joan Chittister.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: In Joan Chittister’s half-century as a Benedictine nun, the world has changed dramatically and so has her church. As a young woman, she believed she had to put aside her love of writing for religious devotion. Today, she’s the author of more than 30 books. As a young nun, for 25 years she wore a habit, but when I first met her a decade ago, she was wearing a suit of purple and carrying the laptop that never leaves her side. Sister Joan has emerged as a passionate public religious thinker about what she calls this “crossover moment in history.” All of the large human questions, she says, demand new thinking. Here she is in a recent exchange with Tim Russert on Meet the Press.

MR. TIM RUSSERT: Are you concerned that some Catholics do not feel welcome in their church because they have disagreements on issues like stem cell research or on gay rights or abortion or death penalty?

SISTER JOAN CHITTISTER: I’m simply asking that all of us realize that the answers we have right now in those arenas may well not be final answers, that we’re all struggling to find the best answers. We all say that life is our greatest value, but life has never been an absolute value. Having religion in the public arena is one thing, politicizing it is another. If we do that, we’ll lose pluralism for puritanism. We’re risking the country at the same time.

MS. TIPPETT: Over the years, Joan Chittister has increasingly engaged with other faiths. She’s recently co-founded a new national movement, the Network of Spiritual Progressives. She also co-chairs a global consortium of women religious and spiritual leaders. Her drive towards reconciling a diverse world had its roots in the smaller world of her childhood. Her biological father died when she was three years old, and her Roman Catholic mother married Dutch Chittister, a Presbyterian. They decided to raise her as a Catholic, but Joan Chittister’s future theology was deeply shaped by the fact of her parents’ then-scandalous mixed marriage.

SISTER CHITTISTER: I learned two wonderful and distinct things from these people. From my mother’s Catholic upbringing, I learned that all life is sacred, all things are sacramentals, meaning revealing the presence of God. But from my father, I learned there was the word of scripture, that was the foundation for any word of the church. And from him, I learned this unerring and just intractable, implacable commitment to truth. He just kept telling me that the one thing that mattered in life is I had to tell the truth, I had to be truthful. Now, when I look back now, if anything, I realized in those two people, in that microcosm and that mix, that holiness, like God, has many faces and speaks in many languages.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, you told me a story, but I want you to tell it again because I never forgot it, about a day, I think it was in second grade, when you learned that your father would go to here because he was a Presbyterian.

SISTER CHITTISTER: You’re right.

MS. TIPPETT: Tell that story.

SISTER CHITTISTER: I was in second grade, as you said quite correctly. That day in religion class, Sister taught that Protestants don’t go to heaven. I can remember when I retell that story the terrible shock that went through my system. I mean, I was seven and a half or eight years old, and I knew we were in trouble. I was also very, very worried about the information. Why? Because there was a custom in my house — I was an only child — and my father and I would commonly get home at about the same time, he from the shop and I from school. And when we walked into the house, the minute we got in the house and the hellos were over, one of them would turn to me and say, “And, Joan, what did you learn in school today?” Well, that’s the day I learned the blockbuster stuff, that none of my Chittister relatives were going to heaven. I shot out of that school as fast as my little legs would carry me, I took a shortcut home, I went screeching into the house. My mother was in the kitchen, and she said to me, “Well, you’re home early and all excited. What happened?” I didn’t say anything. She said, “Well, honey, what did you learn in school today? What happened in school today?” And I looked at her and I said, “Today I learned that Protestants don’t go to heaven.” She said, “Is that right?” and “What do you think about that, Joan?” And I remember looking at her hard and thinking for a second, and I said, “I think that’s wrong.” And she said, “You do? You think that’s wrong? Well, if it’s wrong, why do you think Sister would say it?” And I said, “Because Sister doesn’t know Daddy.” And I can remember her taking a step toward me and she put her arms around me, she pulled me toward her and she gave me a hug and she said to me, “You’re a very smart little girl. I’m proud of you. What did you say to Sister?” And I was ashamed, and I looked down and I said, “I didn’t say anything.” And she said, “That’s fine, dear. That was the right thing to say today. You can tell Sister later.”

MS. TIPPETT: Since that day in second grade, Joan Chittister has spoken out often. She’s done so as a Benedictine nun. At the age of 16, she entered Mount St. Benedict’s Monastery in Erie, Pennsylvania, and has been part of that community now for over half a century. St. Benedict of Nursia described a monastic pattern of life known as the Rule of Benedict in the mid-sixth century. The Rule describes spiritual doctrines and a rhythm of daily life to embody Christian values in practice in community. Joan Chittister was captivated by the very idea of monastic women when she was three years old. She still vividly recalls this moment, which occurred after her biological father’s death when her mother took her to the funeral home to view his body.

SISTER CHITTISTER: So she took me to the funeral home, and she picked me up at the casket, held me in her arms. And when I turned to look at her, I looked down the casket, and here were three of the strangest-looking creatures I had ever seen in my life. I learned later they were sisters of Mercy in the old habit, in the big linen headgear and the veil and the big sleeves and the cincture around the waist and all the pleats and wool and everything that went with it. They were sitting at the end of the casket, and I said to my mother, “What are those?” Not “Who.” “What is that thing?” And my mother said to me, “Those, Joan, are special friends of God’s and special friends of Daddy’s. And when the angels come to get your daddy, the sisters will stay here and they’ll say to the angels, ‘This is Joan’s daddy, and he was a wonderful daddy and a wonderful man, and you should take him straight to God.'” Now, I remember saying to myself, thinking to myself, “That would be a wonderful thing to do in life. You could give other little girls’ daddies to God.” So I spent the rest of my life crossing streets so I could say hello to nuns and just simply following them around.

MS. TIPPETT: And you could always recognize them back in those days.

SISTER CHITTISTER: You could recognize them. And you could spot them coming in 10 miles and you could plant yourself in front of them so you could say, “Good morning, Sister.” So I can’t explain that. I can only tell you that for somehow or other, at that early age, that seed was planted. I went to a Catholic school, I had wonderful sisters, loved every minute of it. It was a very natural progression for me.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, some of the women I most admire in the world are monastic, and I know the Benedictines up in St. Joseph. And recently I spent some time with some Adrian Dominicans in Siena Heights, Michigan. And I was with some of the sisters from that community who were probably about your age and such intellectual, sophisticated, wise, you know, powerful women. It struck me that — and you’ve been a religious for, what, 50 years, is that right?

SISTER CHITTISTER: Fifty-two years.

MS. TIPPETT: Fifty — so that 50 years ago, that entering this religious life was a very kind of powerful and radical move for a woman, a liberating move in a way that is counterintuitive for us now. When women — I mean, when I suppose the other path that was laid out before you is that you would marry and that your life would be defined very much by a man and a family.

SISTER CHITTISTER: That’s right.

MS. TIPPETT: And this was a completely different way to be. I think it’s worth remembering that because our culture has changed so much.

SISTER CHITTISTER: Well, it’s a wonderful life.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, say some more about that, because I don’t think that that’s, you know, automatically something that modern people would infer.

SISTER CHITTISTER: Oh. Yeah. Not to infer that is to miss the whole meaning. It’s a wonderful life. It’s a happy life, it’s a productive life, it’s a meaningful life, and it’s a deeply spiritual life. I mean, you immerse yourself in the spirit of God, in the scriptures, in the great tradition, in the values, in the simple things about which life really exists. It’s not about money. We take vows of poverty, for instance. You know, the whole world is coming to understand that there’s nothing wrong with our attitude toward that. Things aren’t going to do it for you. We take vows to listen, to obey the word of God in our life, to understand that there’s something other than ourselves that should be dictating what I do with our lives. And we take vows of stability, of relationships. I’m an Erie Benedictine. We grow here. You know that poster that went around a couple of years ago, “Bloom where you’re planted.” Whatever happens to Erie happens to us. We don’t just pick up and find a better place on Wall Street next week. We stay with these people, raise these people, worry about these neighborhoods. So the whole notion of shaping your life, consciously knowing the values that you’re about is itself extremely liberating. Being a woman religious is still a phenomenally liberating moment for a woman. Why? Because she comes into the fullness of herself and spends her life concentrating on the fullness of herself, but not for her own purpose alone, but to bring to the world the best that is in her. We’re saying, in a way that the Army never thought of, be all that you can be because the world needs you.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, I also want to point out that, like the Army, you see the world. Right? I mean, you can…

SISTER CHITTISTER: I do.

MS. TIPPETT: …go where you want to go. I mean, you can say that you are planted in Erie, and I believe you. I also know that you’re one of the freest spirits I’ve ever encountered. Like many monastics, you are a world traveler. So talk to me about, you know, on the one hand, as a monastic, it is a contemplative life, but your life is also very much a life of action. Is there a tension in that? Or how do those two things work together?

SISTER CHITTISTER: It’s a natural and a necessary tension. Even monastics who are not in a position, like I and some others are, to travel so much, they leave their houses open. They are continually making themselves available to the needs of others, taking people in if only for retreats themselves, but always, always saying that “This space doesn’t just belong to me, it is mine for the sake of other people.” You can’t hear the cry of the poor in prayer five times a day and not somehow or other become sensitized to the needs of the poor, and therefore, respond the best you and your community can. Right now, we’re at another point in the development of the world. In some ways, the Europeans have known it 200 years before us. In Europe, it’s almost impossible to travel 250 miles without finding yourself in somebody else’s country, so Europeans have always been national, international travelers. In the United States, we’ve lived on a very, very large ice cube that’s melting now. The world is coming in, the boundaries are going down. What we’re about now is the unification of the world. That means that the whole world is not going to come to us; we have to be prepared to walk with the rest of the world on the path it knows. So, in my own life, I don’t see them as separate. If I weren’t immersed in my community. I couldn’t do it, I wouldn’t have the physical energy nor would I have a reason to do it. We simply set out to do outside what we do inside. We live with strangers. We say everybody is welcome here. We say, yes, come. So when I find myself, as I will next week, for instance, in Taiwan, it won’t feel any different to me than Erie does.

MS. TIPPETT: Author, global activist and Benedictine nun Joan Chittister. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “Obedience and Action,” a conversation with Joan Chittister.

MS. TIPPETT: Talk to me about the Rule of Benedict. You live under a rule. What does it mean for you to live by that Rule of Benedict?

SISTER CHITTISTER: Well, you have to begin by realizing that what the word “rule” means to a contemporary American in the year 2006 is not necessarily completely or only what the word means in a document that was written in Europe in the sixth century. “Rule,” regla, meant “guide,” “guideline.” It was like using a railing going up or down a set of stairs. It was there to help you.

MS. TIPPETT: Something to lean on.

SISTER CHITTISTER: That’s right.

MS. TIPPETT: It’s something to get you there.

SISTER CHITTISTER: It’s a crutch. It’s the way you get to where you’re going. It is an ideal, and it has something to do with living a lifestyle. We’re not a work, we’re not an institution, we’re a lifestyle. The Rule never asks for any kind of rigid conformity. The Rule says, “Here are the scriptures, live in them. Here are your brothers and sisters, live with them, love them all, bring them all to light. Here’s the world around the monastery, take it in. Do your own work, support yourself, don’t expect anybody else to support this monastery.” The Rule says we earn our bread by the sweat of our brow just as our — as the ancients before us. So it’s a hard-working, simple group of people who are living, modeling what it is to be part of the world, to take care of the stranger, to grow together. You live in community because it’s only community that really shows us who we are — who we are, what irritates you, what bothers you, what don’t you want to do? Those are exactly the things that you need to work on today.

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder how the vow, the virtue of obedience, the meaning of that has changed for you in this half-century as a religious, and as you move through the end of the 20th century and into the 21st century.

SISTER CHITTISTER: Well, it has changed, and there’s no question about that. When I entered the community, obedience was more a military virtue than a Christian virtue. And there was, at that time, a tremendous emphasis on conformity. That’s the life that had been developed as a result of, for instance, the industrial age. And you’ve come to understand assembly lines. When you depersonalize the human being for the sake of the product, you know—

MS. TIPPETT: And you’re saying even those cultural values had sort of infiltrated monastic orders.

SISTER CHITTISTER: Of course. That whole notion of the military meaning of obedience had, whether we realized it or not, begun to consume us. And worse than that, we were women, and women were expected to conform. So it’s not until after World War II when education itself became as possible, at least in some ways, for women as for men and then became as important for women as for men, as it is now, that you begin to see this shift from military conformity to a sensitivity to the impulses of grace in our lives. The word “obedience” comes from the Latin word oboedire, “to listen.” And the first word of the Rule of Benedict is “Listen, my children, to the precepts of your teacher.” Listen to them, learn from them. Not “Jump.” “How high?”

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder if you’d talk about some of the concrete ways in which, as you say, this move from obedience, which is about conformity, to obedience, which is about being sensitive to and responsive to grace.

SISTER CHITTISTER: Oh, that’s easy.

MS. TIPPETT: Talk — give me some concrete examples of how you are different as a person of faith, as a Catholic, as a woman religious.

SISTER CHITTISTER: Now, as opposed to the ’50s. Sure.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. What that has meant specifically in your life, in your theology.

SISTER CHITTISTER: Oh, it’s been terribly important. For instance, the change that occurs when we, like the rest of the world, remember we are not an entity unto ourselves, we are the people of our time and culture. As the years went by and Vatican II came with it, we discovered that the individual is a precious resource and that simply cookie-cutter people is not the goal of our life, that that doesn’t make you holy or holier. To be other than you can be is no sign of great spiritual valor. So as we discovered this synthesis of the gifts in the individual and the needs of the times, as well as the nature of the community, we discovered that we were a more active, more effective, certainly happier and freer group if we were following the gifts of the members.

MS. TIPPETT: Author, global activist and Benedictine nun Joan Chittister. In 2001 she attended an international conference on the ordination of women, despite a Vatican request that she not go. She cited her Benedictine understanding of obedience, which she believes is about dialogue rather than control in a spirit of co-responsibility. In April 2001 Joan Chittister delivered the keynote speech at a national conference for Catholic educators held in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Here’s a passage from those remarks.

READER: Benedict of Nursia assessed his world, asked why the few controlled the many and envisioned a whole new way of living that was the antithesis of the hierarchialism of Roman patriarchy. Mother Jones, who at the age of 80 was called by a U.S. congressman the most dangerous woman in America, assessed her world, asked how power could be redistributed and helped to shape an economic world where workers had the right to unionize. Oscar Romero assessed his world, asked where political legitimacy was, and lost his life to stop oppression. Indeed, the tradition is clear. Spiritual leadership is about assessing reality, about reclaiming the cosmic vision, and about being courageous enough to ask the right questions along the way.

From a speech by Sister Joan Chittister.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, Joan Chittister shares her thoughts on women and the Catholic Church, openness to other faiths, and why so many people in our time are getting religion from books, as she says, “church off the shelves.”

Continue this exploration at speakingoffaith.org. This week, find Sister Joan Chittister’s speeches and writings. Look for the Particulars link. If you missed a part of this program or want to hear it again, you can download an MP3 to your desktop or subscribe to our weekly podcast. Listen at any time, at any place. Also, sign up for our free e-mail newsletter. All this and more at speakingoffaith.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Obedience and Action,” a conversation with Sister Joan Chittister.

In over 50 years as a Benedictine monastic, or religious, Joan Chittister has emerged as a fiercely faithful and challenging voice in Roman Catholicism and in global politics. She writes a regular column for the National Catholic Reporter, and she’s published more than 30 books, among them Wisdom Distilled From the Daily.

MS. TIPPETT: You are very well-known as a woman speaking about women, about feminism within the church and outside the church. I wonder if you’d talk to me about how that came to be a part of your passion, you know, and what does it mean? And I think there are probably people out there who might find this description to be a contradiction in terms, to be a Roman Catholic feminist religious.

SISTER CHITTISTER: Well, in the first place, feminism, as far as I’m concerned, is a very holy thing. Now, feminism is not monolithic either.

MS. TIPPETT: When did you start to think about feminism?

SISTER CHITTISTER: Well, the funny thing is I’m one of these people who probably backed into it. I was probably a feminist, like I think most women are, actually, without knowing it. I never fooled around with the word. I was one of these people who said, “Well, I’m not a feminist, but I do believe that women should be paid exactly the same thing a man would be paid for the same work. I’m not a feminist, but I don’t understand why husbands and wives aren’t both raising small children. Who said that a husband can’t change a diaper? I’m not a feminist, but why do we talk in church only about the men and the sons and the boys? I mean, what about the rest of us? We’re here.” And then one day I came across a quatrain that went something like this, “Mama, what’s a feminist?” “A feminist, my daughter, is anyone who thinks or dares to take in charge her own affairs when men don’t say they oughter.” And that was a quatrain by Alice Duer Miller in 1928. And I knew immediately that I qualified. It became very clear to me that feminism was not about femaleness, that the feminist philosophers had been talking to us about the fullness of all humanity, about the world being a better place if we were using all the gifts of the human race instead of just half of them.

MS. TIPPETT: What I think you’re saying, what I’ve understood from reading you is not that women are superior, but that women bring other questions and perspectives to the table.

SISTER CHITTISTER: Oh, yeah. This is not a case of…

MS. TIPPETT: No. I mean — you know, because there’s the simple argument, which I don’t buy as a woman, that “If only women ran the world, everything would be wonderful,” because women can be…

SISTER CHITTISTER: Yes. Oh, no, no.

MS. TIPPETT: Women have their problems, too. But you’re — but I think the way you framed it a moment ago, that, you know, why not use the gifts of the other half of humanity as well?

SISTER CHITTISTER: We — I always say, you know, we look at questions with one-half of the human brain, we make decisions with one-half of the human brain, we see with one eye and we stand on one leg, and our decisions show it. This is not a question of superiority. We cannot replace male chauvinism with female chauvinism. The scriptures will not support that. But we can remember that both Adam and Eve were responsible for the Garden, and somehow or other we had better get back to that awareness because you look at the front page of your paper today, we’re in a mess.

MS. TIPPETT: And you are part of a church which does not ordain women, where Communion is such a central sacrament in any Catholic life and in monastic life, which can only be performed by a man — a priest. I know that within the Catholic Church, some consider you a hero and some probably a heretic for speaking out about this. I mean, talk to me about how your discernment on women in your church has developed in your lifetime.

SISTER CHITTISTER: Well, in the first place, you have this tradition from the Greek philosophers through the Catholic theologians that defined men and women quite differently. Now, after the 19th century, here we have coming in left-hand part of the stage this thinking, producing, creating woman, and we have to deal with her differently. The old biology has failed us.

MS. TIPPETT: But the — you know, the simple argument, which I also read in — got off the Internet, which was a Catholic authority writing about your ideas, was, you know, the idea that is put forward not just in the Roman Catholic Church, that Jesus was a male, that Jesus’ disciples were male. And I’m not sure how true this is to the history we’re uncovering now, but that all the early church leaders were male. I mean, that’s the argument that’s still kind of the bottom line.

SISTER CHITTISTER: But — yes, but…

MS. TIPPETT: How do you respond to that when you’re in discussions?

SISTER CHITTISTER: Well, Jesus was also a Jew, and I don’t know any Catholic priests who are. That very discussion — the two sides of that discussion are what demand the universal discussion of the role of women in the church. At the end of that discussion, we may all decide we want it just the way it is, for whatever reason, but not for a false reason. The very fact that you don’t discuss it is the problem. It’s not the answer that’s the problem. I am calling for the discussion of this issue, because if we don’t face it as Catholics — you realize that the women in first grade right now are growing up with great expectations about themselves, and every institution on earth is beginning to honor those expectations except one. The only place they’re going to find themselves excluded by the time they’re 25 will be the church. Is this going to be a great model of the love of God for women?

MS. TIPPETT: And I suppose that the response of orthodoxy, or a response would be that sometimes the church will be, might be, the single institution which is not following culture. Right?

SISTER CHITTISTER: Well, sure, that’s — and that’s an acceptable answer. But you’ve got to have a better reason than the one that’s being given, because theology and science are question marks to it.

MS. TIPPETT: I think something I’ve always been intrigued by in Benedictines — I also think I’m hearing this in you but you’re not saying it, but — is a long view of time, that progress sometimes takes hundreds of years. This is not an instinct that Americans have culturally.

SISTER CHITTISTER: No.

MS. TIPPETT: But, you know, you’re extremely passionate, you’re out there working on this, but I don’t hear you being impatient in the way our culture might be impatient.

SISTER CHITTISTER: No. No. Let me give you two things. One, the church is a human institution, and it is slow. It’s also a universal institution. It takes a long time for ideas to seep to the top, let alone to move the bottom. So you just realize that what is going on right now is simply the seeding of the question. It comes down to how many snowflakes does it take to break a branch? I don’t know, but I want to be there to do my part if I’m a snowflake. Now, I’m a woman. How many women’s voices will it take before we honor the woman’s question? I don’t know. But I am conscious, and therefore I am responsible.

MS. TIPPETT: Author, nun and activist Joan Chittister.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “Obedience and Action.”

Sister Joan Chittister liberally sprinkles her speeches and writings with passages from the Tao Te Ching and Sufi mystics. She’s co-chair of a global interfaith consortium of women, religious and spiritual leaders. Joan Chittister has grown increasingly open to the insights of other faiths in her own life and work. In recent years, the Vatican has grown less embracing in some official documents. But Joan Chittister says there is no contradiction for her in being a faithful Catholic religious and a partner to people of other traditions.

SISTER CHITTISTER: Go back to where I began in, quote, “a mixed marriage.”

MS. TIPPETT: A Presbyterian and a Roman Catholic.

SISTER CHITTISTER: That’s right. And then realize that that openness in me, that awareness of that struggle in my own lifetime, that kind of theological exclusionism stopped in my lifetime. The institution itself decried that kind of thinking and has done much to repair it. Now, when you find yourself a participating member of the human race with all of the global implications that that has, and, as you implied in my own situation, where in the Woman’s Global Peace Initiative I am a co-chair with a Hindu nun and a Buddhist nun and an Orthodox Jew and an Islamic scholar and a Protestant clergywoman, that the six of us are calling people together, women together, in areas of conflict around this world to be a living sign that no religion, the heart of none of the great religions really supports, endorses or sets out to produce war or killing or death for anyone. So what I have learned is that God works in many ways on this globe and that the scriptures of the other have insights for me that basically confirm my own insights. They don’t weaken my Christianity or my Catholicity. If anything, it tells me more clearly who I am, but it also tells me, very profoundly and respectfully, who these other people are. If God is one, why would it be so surprising that the six of us would have a oneness in ourselves if we’re really women religious?

MS. TIPPETT: Here’s a sentence, a question from one of your writings. “The problem of the nature of faith plagues us all our lives. Is openness to other ideas infidelity or is it the beginning of spiritual maturity?”

SISTER CHITTISTER: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: It’s a good question.

SISTER CHITTISTER: Well, you see, the old institutional answer was that it’s infidelity. But if you move as a person of faith, immersed in your own — the best of your own spiritual tradition, then you can only come to the other end of that sentence, “It is openness to the best and to the wholeness.” We don’t have gods, we have God. We are all moving toward that God within the limitations and with all of the gifts that each of these great, seeking traditions gives us in our culture. Now, where all of that is going to come out, it doesn’t even bother me. I just know that the Jesus story is my story, that I walk with Jesus, that I feel that presence, that I know that path, and that that path, the path I walk, to me seems very much like the path from Galilee to Jerusalem that Jesus walked, raising women from the dead and curing lepers. I am convinced that where I am going is on just the end of the path that I started years ago.

MS. TIPPETT: Tell me what else you’re doing these days, where your passion is. I noticed that you were part of a gathering that did get quite a lot of attention, of the Network of Spiritual Progressives in Washington that was hosted in part by Michael Lerner and the Tikkun Community.

SISTER CHITTISTER: Well, I’m a co-chair with Michael of Tikkun, yes. And I have done it because I believe that we have a very limited and often distorted image of the voice of religion in our own culture and our own time. Somebody said to me in another radio interview, “Now, Sister Joan,” the interviewer said, “you know, the last election was decided on moral values.” I said, “Wait a minute. Just hold a minute. Hold it. The last election was decided on some moral values.” The place of religion right now is to remember the rest of the moral values.

MS. TIPPETT: What are those for you?

SISTER CHITTISTER: Well, one of them has something to do with whether or not you can take a baby to an emergency room in this country, the richest country in the world, and have that baby treated or not. We have 10 million babies, as you and I speak, without health insurance in this country. It’s wrong. It’s immoral. And the whole notion that private sexual morality is the definition of religious life in this country is a cute ploy. It gets our minds off of the sins that are really killing the greatest number of people. I’m not saying that those are also not important values. Of course they are. They define our character as a people and our ability to live within our relationships. But there’s a big difference between being pro-life and pro-birth. It’s easy to get a baby born. What I want to know is once that baby is born will you feed it and house it and educate it? All I see is that every day we reduce those figures in our national budget more and more. That’s the morality and the religion that I’m talking about. And until we care about those things, we cannot, on either spectrum, left or right, call ourselves a religious people, I don’t think.

MS. TIPPETT: I want to ask you something about spirituality in our time. You used a phrase with me, which I’ve quoted many times, and you said, “A lot of people these days are getting their religion off the shelves, out of books.” Now — and you’re part of that. You are an incredibly prolific author, but it’s just an explosive field of reading about religion and finding religion in many different ways. I’m just curious about your wisdom — people ask me often, “What’s that about?” The fact that sort of, you know…

SISTER CHITTISTER: Oh, sure.

MS. TIPPETT: …that The New York Times book list is not just The Da Vinci Code; it’s five titles on the nonfiction list. Now, what’s that about? What’s your answer to that question?

SISTER CHITTISTER: Oh, I think that’s very simple. We’re at a crossover moment in time, meaning we’re at a point where the — we have so many new questions, but we don’t have — the new answers have not emerged. They’re only beginning to simmer in this stew that is humanity. The old answers don’t suffice; and if they suffice, they don’t satisfy. You know, since John Glenn took that first picture of that blue globe swirling in black space, we suddenly had all sorts of new questions about ourselves. You can go down every single question in the human agenda today: What is life? Do we know anymore? Once we got Dolly, once we cloned a sheep, was the definition of life so clear, so pat, so stable anymore? We are the people in the desert. We’re the people between the questions and answers on one side and the questions without answers on the other side. People are not hearing those answers in their churches, and people know intuitively that sometimes the answers demand more than what church language can bring to them at that time. Can we get values from our churches? Of course we can, and we do. But what do I do — what is the ethics of what’s going on in corporate America right now or political America right now? How do I know what ethics is? Do we really have a republic, let alone a democracy, or have we suddenly found ourselves the inheritors of a political oligarchy? What is oligarchy? What does it have to do with spirituality? Does anybody want to know? So where do I go if I can’t get it in a pulpit? I go to a bookstore.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. But, you know, it’s — in a sense, isn’t it interesting that writing, which was your earliest calling, perhaps, which you put away for a while, thinking that you had to put it away to be religious, has become more of a ministry, more of a kind of vital ministry in the world than you could ever have imagined?

SISTER CHITTISTER: I tell myself that every morning. I say to myself, “How did this happen?” But somehow you have to believe that these things are not accidents, that you might be in the right place doing the right thing.

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder if the decline in numbers of women religious is a source of sadness for you.

SISTER CHITTISTER: Does the declining number of women religious make me sad? At one level, of course, yes. These were the sisters in the large communities that raised me, and I will be forever grateful. I wouldn’t be who I am without those women in my life. At the same time, it’s interesting; the question about the numbers of religion is a capitalist question to…

MS. TIPPETT: How big is it? Right.

SISTER CHITTISTER: It’s a capitalist answer to a Christian question.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

SISTER CHITTISTER: We — religious life is not a numbers game. There are, in every single culture and in every great religious revelation in every continent of the world, those figures who embody the spiritual search and keep confronting the entire culture with the spiritual questions of the time. That can be one person or a million people or 100,000 people, it doesn’t make any difference, but we all recognize them. We call them swamis and Sufis and priests and ministers and nuns. They’re there, and they have always been there, and they’re always going to be there. So is the old form where we had become a very strong — a very large and strong labor force that had…

MS. TIPPETT: You mean monastic — the whole monastic network?

SISTER CHITTISTER: Yes. Had raised these hospitals and colleges and schools, created a whole institutional culture and network that really led and bred the country. But now they’re there. Hospitals are mainstream, colleges are mainstream, schools for women are mainstream. That must mean, then, that we are called to something else, and that may not need numbers, or it’s very possible, very possible, that this older form is indeed declining while this newer form is emerging. But is religious life going to go, and is — are numbers its definition? No, it’s not going to go, and numbers will not determine its effectiveness.

MS. TIPPETT: Joan Chittister is a sister of Mount St. Benedict’s Monastery in Erie, Pennsylvania. Her latest book is Called to Question. Here in closing is a story she tells about her vision for the future.

READER: In the mid-17th century, Spanish seafarers sailed up the west coast of the Americas to what is now known as the Baja peninsula. The cartographers of the time simply drew a straight line up from the Strait of California to the Strait of Juan de Fuca between Vancouver Island and Washington state. Consequently, the maps that were published in 1635 show very clearly that California was an island. For 50 years, then, the years of the most constant, most crucial explorations of the California coastline, those maps went unchanged because someone continued to work with partial information, assumed that data from the past had the inerrancy of tradition and then used authority to prove it. Finally, after years and years of new reports, a few cartographers, the heretics, the radicals and the rebels, I presume, began to issue a new version, and in 1721, the last mapmaker holdout finally attached California to the mainland. But — and this is the real tragedy perhaps — it took almost 100 years for the gap between experience and authority to close. It took almost 100 years for the new maps to be declared official despite the fact that the people who were there all the time knew differently from the very first day. Vision is the ability to realize that the truth is always larger than the partial present. The map you use to explore this new world will be the path by which the next world walks.

From a speech by Sister Joan Chittister.

MS. TIPPETT: Contact us with your thoughts at speakingoffaith.org. You can catch this program again and hear others in our archive in many ways, download an MP3 to your desktop or subscribe to our free weekly podcast. You can also sign up for our e-mail newsletter, which brings my journal on each topic straight to your inbox. That’s speakingoffaith.org.

The senior producer of Speaking of Faith is Mitch Hanley, with producers Colleen Scheck and Jody Abramson and editor Ken Hom. Our Web producer is Trent Gilliss with assistance from Ilona Piotrowska. Kate Moos is the managing producer of Speaking of Faith. The executive producer is Bill Buzenberg. And I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.