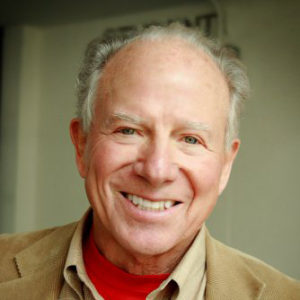

Stuart Brown

Play, Spirit, and Character

Who knew that we learn empathy, trust, irony, and problem solving through play — something the dictionary defines as “pleasurable and apparently purposeless activity.” Dr. Stuart Brown suggests that the rough-and-tumble play of children actually prevents violent behavior, and that play can grow human talents and character across a lifetime. Play, as he studies it, is an indispensable part of being human.

Image by Mi Pham/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Guest

Stuart Brown is founder and president of the National Institute for Play near Monterey, California. He is co-author of Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul.

Transcript

June 19, 2014

STUART BROWN: I could ask you as a parent and any other parent that’s listening with a young child, you know, say a child over 3 but under 12. And if you just observe them and don’t try and direct them and watch what it is they like to do in play, you often will see a key to their innate talents. And if those talents are given fairly free reign, then you see that there is a union between self and talent. And that this is nature’s way of sort of saying this is who you are and what you are. And I’m sure if you go back and think about both of your children or yourself and go back to your earliest emotion-laden, visual, and visceral memories of what really gave you joy, you’ll have some sense of what was natural for you and where your talents lie.

[Music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: Who knew that we learn empathy, trust, irony, and problem solving through play — something the dictionary defines as “pleasurable and apparently purposeless activity.” Dr. Stuart Brown suggests that the rough-and-tumble play of children actually prevents violent behavior; that play can grow human talents and character across a lifetime. Play, as he studies it, is an indispensable part of being human.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

Stuart Brown founded the National Institute for Play at the age of 63, after too many years, as he puts it, as a workaholic doctor. His mission is to bring the unrealized knowledge, practices, and benefits of play into public life. I interviewed him in 2007.

MS. TIPPETT: Where I’d like to start with you is where I start with every interview, whatever the subject is. I’d like to just hear a little bit about, let’s say, your background spiritually as well as your background of — as a person who plays.

DR. BROWN: Well, you know, I’m reasonably old and I’m sorry, I’ve only got 90 minutes. [laughs]

MS. TIPPETT: I did see somewhere you made a reference to Midwestern Presbyterians, I believe speaking of your parents. And they’re not famous for their playfulness.

DR. BROWN: Well, I had a — they were Midwestern Presbyterians. I grew up on the southwest side of Chicago. And my mother was one of the trustees of the Moody Bible Institute.

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, wow.

DR. BROWN: My father was an organic chemist, an inventive fellow, very playful. So I grew up in an atmosphere that had kind of free play and also religious overtones. I did go to a parochial high school called Christian High and then to Wheaton College.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

DR. BROWN: So I had a certain sense of deep belief, and I revelled in that deep belief, which was certainly part of my religious background and, I would say, my spiritual heritage.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. And in your history there is a quite striking and surprising straight line it seems between your interest in play and an early study — psychiatric study you became involved in in extreme violence. Tell me about that line.

DR. BROWN: Well, that line of course opened play up to me in a very unexpected way. In 1966 when I was just beginning to take over and office as an assistant professor of psychiatry, a young man by the name of Charles Whitman went up to the Texas Tower in Austin, Texas, after killing his wife and mother. Perpetrated what was then the largest mass murder in the history of the United States, killing 17 additional people and wounding 41. And because I had done some studies of violence in the course of my residency in neurology and psychiatry, and because in August in Texas most people who are important are elsewhere, I was put in charge of the behavioral aspect of trying to figure out why Charles Whitman did this horrendous crime. And we brought in, uh, the world’s experts to try to figure out the motivation of Charles Whitman, even though he had been killed by vigilante crossfire at the top of the tower.

And so for a very intense period of time, in addition to doing very detailed toxicologic and — studies of his body, we retrieved as much information as possible from his prenatal area all the way up to the last hours before he died. And without going through that entire story, one of the major conclusions, which struck me and has certainly stuck with me since, was that a remarkably systematic suppression of any free play — which was largely the result of his father’s overbearing and intense personality — prevented Charles Whitman from engaging in normal play at virtually any era of his life, including his early infancy.

MS. TIPPETT: Now did you then continue on and find that to be a factor in the lives of other violent individuals, homicidal individuals?

DR. BROWN: Yes, I did. We thought at the end of the Whitman study that this was such a bizarre aberration in human behavior that it probably was not something one could generalize from. So as a result of the funding available and the availability of research subjects in the prison system in Texas, a team of us then studied all the young murderers whose crime was essentially homicide without their being career criminals, uh, and we did an indepth study of them, their families, and compared them to as well-matched a control and comparison population as we could. And, lo and behold, we discovered that the majority of them — in fact 90% level — had really bizarre, absent, deficient, seriously deviant play histories.

MS. TIPPETT: Now, is that just one symptom among others of other kinds of abuse or neglect? Or did it seem to be a quality of these lives sort of in and of itself that…

DR. BROWN: Well, I don’t know that I can answer that question specifically, because abuse was part of the homicidal population…

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

DR. BROWN: …both Whitman and the young murderers we studied. But if you sequentially sort of watch a life emerge and you look at what play offers from early infancy into adulthood, when crucial experiences are missed, the ability to regulate emotions and to establish empathy and to live with trust with one’s companions is definitely attenuated, or definitely constricted. So that, from my standpoint, although there are other factors that are certainly — allow one to have a proclivity for violence, the play history and its aberrations or lack are — have proven the test of time to be extremely important in the life cycle of highly violent men, at least.

MS. TIPPETT: Let’s talk about what you mean when you use the word play when it’s something that you associate so closely with words like empathy and trust. You know, what’s your working definition?

DR. BROWN: [laughs] Go to the Oxford dictionary and you’ll find at least 50 definitions, but, uh, to start with I’d say play is anything that spontaneously is done for its own sake. And then one can extend that into more and more detailed definitions such as “appears purposeless,” “produces pleasure and joy,” “leads one to the next stage of mastery.” In terms of biology, “appears to be the product of,” what I call, “divinely superfluous neurons.” There is choice… [laughs]

MS. TIPPETT: Right…

DR. BROWN: …in the player’s life. And that choice, if given opportunities through the environment, emerges innately and spontaneously if the individual, or animal for that matter, that’s capable of playing is safe and well fed.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, you said “appears purposeless.” And I’m thinking what difficulty some parts of our culture have with anything that appears purposeless.

DR. BROWN: So true.

MS. TIPPETT: I wouldn’t — yeah, I probably would put myself in this category at certain points in my life. Something that appears purposeless would probably lead to anxiety rather than joy for me.

DR. BROWN: Well, I hope not. I hope part of the outcome of this discussion with you and your audience is a little guilt-free purposelessness. [laughs]

[Music: “Instrumental 1” by Wes Swing]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today with Dr. Stuart Brown: exploring the place of play in human spirit and character.

MS. TIPPETT: And, you know, and you mentioned animals. And it is very intriguing to look at the work you do with the National Institute for Play, but also how much you’ve been involved in the science of play, which encompasses both animals and human beings. When I use that phrase, the science of play, what comes to mind for you? There’s this whole world, this whole universe of a different kind of science that you have been immersed in, that the rest of us probably don’t even know about.

DR. BROWN: Well, I think that’s true. And I think that’s the science of play. And having had a background in medicine and psychiatry and neurology primed me, I think, to see play behavior in its evolutionary terms. So that when I had the option — fairly late in my career — of studying play in a broad sense, I started with the animals in the wild and learned a huge amount about sort of the spectrum of play behavior in the animal world.

MS. TIPPETT: I’ve looked at some projects you were involved in — an issue of National Geographic, some of the visuals, there are these remarkable images of cheetahs and cranes and bears and mountain goats who seem clearly to be playing.

DR. BROWN: Well, I think there is no doubt, at least to us onlookers, that they’re playing. And my guess is, by all the measurements we can make on the animals, they actually are playing.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. And what do we know about it through science?

DR. BROWN: Well, I think we know a lot about it through the wonderful laboratory rat. They make a particular squeak, that’s inaudible to humans, as a signal that they want to play. They then wrestle with each other and pin each other, particularly during their juvenile times. They engage in what a number of investigators call hardwired rough-and-tumble play. And the outcome of that is quite striking, because if the laboratory investigator stops the rats specifically from playing, there are some dire consequences. They do not socialize normally. They can’t recognize friend from foe. And there are other very specific kinds of outcomes, which to my way of thinking, to some degree, match some of the human outcomes. But, of course, they’re in rat language and human outcomes are much more intricate.

MS. TIPPETT: So what is happening in play that enables it to have that effect on animal development or even human lives? What do we understand about this?

DR. BROWN: Well, I don’t think we understand enough, because the cultural heritage we have is kind of like your guilt.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Yeah.

DR. BROWN: It is that play is trivial. It’s what you do when your responsibilities are taken care of, particularly as an adult. But if you were to follow, as I have at least scholastically and, if not, clinically, if you’re to follow the trail of play in both animals and humans, the beginning point of play in the mother-infant or parent-infant bonding process is kind of the spontaneous eruption of joy and pleasure upon the process of being safely fed and, in the case of the human, when there is eye contact. And the social smile emerges and the infant and the mother begins to coo. That cooing, that’s worldwide. And there is mutual joy. And the brain imaging that’s associated with that shows an attunement between the mother’s right cortex, a non-dominant hemisphere of the brain, and the baby’s.

And then if you build on that and say, ‘OK, the child has experienced that and now they’re growing up a little bit,’ they get some of the same joyful experience from grabbing something, putting it in their mouths when they’re infants, and then a little later, playing with toys, and then ultimately, parallel play with other children and on and on. I could go right on up through the whole life cycle, each of which has more and more intricate, more complex play if the individual is sort of allowed, through the environment, to take advantage of it.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, here’s a statement. This was from an interview you did with Bob Fagen, who studies mammals and birds, bears in particular. And you asked him about the play of bears. And one answer he gave you was, “They play because it’s fun.” And then you probed. And he said also, “In a world continuously presenting unique challenges and ambiguity, play prepares them for an evolving planet.” I mean, that’s a huge idea. I think you’ve said something similar about how play equips human beings to live in the world. But can you explain that to me more?

DR. BROWN: Well, I think, again, this, part of the reason that I pursued a brilliant field scientist like Bob was I was trying to figure out the same question you’re asking. Because even as a trained psychiatrist, I didn’t really, I couldn’t really figure out where it came from, why it’s there.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. BROWN: But when you see animals and humans who are deprived of it, they are fixed and rigid in their responses to complex stimuli. They don’t have a repertoire of choices that are as broad as their intelligence should allow them to have. And they don’t seek out novelty and newness, which is part of an essential aspect of play, both in animals and humans.

So if you look at the human situation, at least for the last 200,000 years or so, our capacity as a species to adapt, whether we’re in the Arctic or the tropics, the desert or a rain forest, appears to me to be related significantly to our capacity and, as developing creatures, to play. And then if you look more closely at the human being, you find that the human being really is designed biologically to play throughout the life cycle. And that, and from my standpoint as a clinician, when one really doesn’t play at all or very little in adulthood, there are consequences: rigidities, depression, lack of adaptability, no irony — you know, things that are pretty important, that enable us to cope in a world of many demands.

[Music: “Rupe Folk Mix” by Chris Beaty]

MS. TIPPETT: Let’s talk about children for a minute and then I do want to talk about adults. Um, I’m interested in the fine line that I think perhaps is more apparent when you’re studying animals or children, between playing and fighting or — right? So as the mother of a son, and I didn’t have this experience with my daughter, but with my son, I do see how he has this rich fantasy life. And it’s often kind of with himself, although there are all kinds of characters in the room who I can’t see. And …

DR. BROWN: That’s wonderful.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Is it, is that good?

DR. BROWN: That’s good news.

MS. TIPPETT: Okay. And so I’ve named it — what he does — “saving the world.” Right? So when he says, “I need to go save the world,” which is a really nice spin, I’ve put on it. But there’s a certain violence. There’s a combativeness to it. And apparently, that’s quite common, as well.

DR. BROWN: It’s universal if it’s allowed to emerge.

MS. TIPPETT: So what is that about?

DR. BROWN: Let me sort of go on a riff about rough-and-tumble play…

MS. TIPPETT: Okay.

DR. BROWN: …which occurs in children both genders, but is a bit more obvious usually in boys. If you are to observe kids, like in a preschool, that are involved with all the exuberance that preschool kids have age 4 — 3, 4, 5, and you watch them at play, it’s chaotic, anarchic, looks violent on the — to the surface. They’re diving. They’re hitting. They’re squealing. They’re screaming. But if you look at them, they’re smiling at each other. It’s not a contest of who’s going to win. And most well-meaning parents and a lot of, certainly, a lot of preschool teachers put the lid on that…

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. BROWN: …because it’s, you know, it’s scary, a little scary for an adult…

MS. TIPPETT: It is scary.

DR. BROWN: …because they don’t remember. And almost, always has pretense and real. It has violence and fantasy, and it is the borderland between inside and outside in making sense of the world. It’s a very important part of free play driven from within by the child’s own personality and temperament in mixing with others. Now, you were surprised when I said things like empathy and trust earlier…

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, yeah.

DR. BROWN: …in our discussion. But think about this. If, if you are in a rough-and-tumble situation, somebody hits you too hard, you know what that feels like. So you’re not going to hit, in general, hit somebody else too hard, because you know what it feels like. And that’s the roots, for example, of an empathic response. And the thing that — none of the murderers I studied engaged in normal rough-and-tumble play. Absolutely none. And if you extrapolate the rough-and-tumble play backwards into animals, they also appear to need it to be able to properly find their place in the troop or the tribe or the pack and develop a social reality to meet their needs.

So your son sounds like he’s doing what’s pretty normal stuff. And I think there has to be reasonable protection by adults, but not the kind of helicopter parent hovering over the situation, which prevents the spontaneity from occurring and the kids from solving their own problems that are age appropriate for them.

MS. TIPPETT: I think that’s really interesting, that even what looks like potentially violent play or, you know, can look dangerous is also a source of learning about empathy and boundaries, I guess.

DR. BROWN: Sure. Well, they’re imposed. And most kids who have had a not-too-toxic or sadistic bully in their midst will gang up on the bully and take care of him. And the bully learns. If the bully spends too much time not experiencing normal rough-and-tumble play, or if the taboos of violence are broken again and again in the home of the bully, then the bully’s got to be removed from the play situation or they will, you know, upset and upend the whole playground. But in general, the kids solve their own problems. And that’s one of the most important things that they learn about themselves. They learn whether they’re strong or not so strong, fast or cagey, verbal or nonverbal, imaginative or something else. And you learn that, generally, on the way up, sequentially, throughout your childhood.

MS. TIPPETT: In some of what you write and the other people you’re in conversation with, you make a distinction between play and contest or competition, although, I think, in our culture, the two often become entangled, and maybe adults even impose that on children’s play. I don’t know.

DR. BROWN: Yeah. This is — this is certainly a sticky wicket. But in trying to sort of organize my thinking about competition and contest, this is where I go back to what appears to occur in nature and what appears to be kind of a natural process developmentally in those children who appear to be having a very normal background in play without too much imposition of cultural pressures on the part of the culture of the parents. And what one sees in general is a natural emergence of competitive activity. And by that, I mean testing one’s skill against the skill of another …

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. BROWN: …without the necessity of domination. And so that that quality of competition appears to be pretty universal — in cliques in girls and in, sometimes, kind of physical prowess in both genders also. Whereas contest, I think, requires a winner, often has an exclusionary quality to it, and is not what you see in animal play in the high primates in nature. You’ll see…

MS. TIPPETT: Really?

DR. BROWN: Yeah. You’ll see handicapping that occurs spontaneously in nature, in which the stronger person allows or handicaps the weaker individual so that the play can continue. If there is a chase, often the chaser becomes a chasee. There isn’t chasing somebody down and then putting him down. So that’s sort of the natural history of play in the wild. And I think there — it is possible for a wise coach or a seasoned parent to deal with a competition where mutual participation, love of the game, personal best — there are ways of dealing with this to keep this — volunteer sports going without it being super contest at the, particularly at the younger ages.

MS. TIPPETT: You make a very interesting and intriguing point about the scientists themselves who you have interacted with over the years — Jane Goodall in Africa, you mentioned Bob Fagen, Marc Bekoff, Irenäus Eibesfeldt, these are all people who study play in animals — and you’ve written, I believe, their immersion in wild play or natural play has altered them. Say some more about that.

DR. BROWN: Well, I, you know, I know, particularly, Jane, Marc, and Bob very well, and Jane certainly was altered by the prolonged exposure and the slow habituation of the chimpanzees in Gombe when she was, you know, what some people at the National Geographic called “Eve in Eden,” but — where she saw and took in, in particular, the mother-infant play of chimpanzees and has written beautiful scientific essays about this and about the qualities that are induced. And when one talks to her about this, she takes on kind of a — I won’t call it ethereal — but it’s sort of a knowingness that this is something in nature that’s beautiful and appropriate and can be incorporated in its own language for humans.

And then I go to Bob Fagen who’s with the bears in the wild for years and years. And I’ve been with him in Alaska up in a tree, hour after hour, watching bear play. And Bob has a kind of a spiritual aesthetic about play that permeates his life. I think, you know, I’ve never really tested this in any way because it would have been inappropriate, but I think that there is a certain quality of optimism and compassion that has occurred through the systematic observation of play over a lifetime.

Certainly, it’s that case, that’s the case with Marc Bekoff, whose writings on animal ethics and human ethics and the origins of morality stem from his long exposure in the wild to coyote play and other animals at play. So I’ve been very impressed by immersing oneself in the study of play. There is a certain either permission or osmosis that occurs that’s good for us.

MS. TIPPETT: I want to name something that — so you talked about scientists, and I’m sensing this applies to you, too, that the more you expose yourself to play that it affects you, it changes you. To me, one of the most wonderful gifts of becoming a parent is that I get a second chance to be playful.

DR. BROWN: You bet. [laughs]

MS. TIPPETT: And I actually think that I wasn’t so good at it as a child, and I — but I think I have a richer play life, sort of with — in watching my children I’m more joyful, in a way, even vicariously, with them, and that that’s an amazing second chance.

DR. BROWN: Well, they’re the professionals, we’re not.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. [laughs]

DR. BROWN: They’re — they’re the ones who are purer in their play than we as adults are. So you’re right on. And, you know, being a grandparent, you get a third chance.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. It, it awakens, I do become aware that it awakens something in me, right?

DR. BROWN: Sure.

MS. TIPPETT: That it’s also part of being human. And it enriches me to be exposed to that, for that to be part of my life again.

DR. BROWN: Well, it’s relearning the languages that are fundamental to play, which are largely non-verbal and emotional and really fairly specific. When you relearn those languages, just like the mother looking at her smiling child, you get a spontaneous burst of pleasure. And that, that’s pretty important.

[Music: “Toritos” by Gaby Kerpel]

MS. TIPPETT: You can listen again and share this conversation with Stuart Brown through our website, onbeing.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[Music: “Toritos” by Gaby Kerpel]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today with Dr. Stuart Brown on the science and the pleasure of play as an indispensable part of being human.

His National Institute for Play seeks to address gaps in scientific and cultural understanding of the importance of play across the human lifespan. Stuart Brown’s studies suggest, for example, that the rough-and-tumble play of children prevents violent behavior, that play can grow human talents and character, and that play can be a glimpse of the divine.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s a lot of concern right now and I know you’ve been quoted in a New York Times article, um, about how in our culture, you know, as you and I discussed a bit, there’s a tendency to clamp down on what looks too wild or dangerous.

DR. BROWN: For sure.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. From what you know and what you study and your sense of what play means for human life, what’s your take on that, how it’s affecting us.

DR. BROWN: Well this is a tough one because I don’t want to foster broken bones and concussions and that sort of thing in kids. But an inherent part of being playful is taking risk. What you don’t want to do is have the risks be excessive. And the natural history of play in the world, both animal and human, is that persistent play increases the risk of death and damage while it’s taking place. But it appears to be absolutely necessary for the well-being and, say, future of the species.

So it is a — it’s a conundrum, but to remove risk, all risk from kids’ play, is to not allow them the spontaneity from within to develop themselves. It’s a judgment call on the part of parents. And I think this is where I have some beef with the media, in that I think “if it bleeds, it leads” — the perceptions of the levels of violence and risk in our culture are really beyond what the actual risks are, so that a responsible parent feels they can’t let their kid be out on the streets in the afternoon and that sort of thing.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. And what I kind of hear you saying — I mean, here’s a quote from something Jane Goodall said: “Play teaches young animals what they can and cannot do at a time when they are relatively free from the survival pressures of adult life.” But I feel like we are so obsessed and I’m, you know, speaking for myself as well, with our children’s safety and so fearful that they don’t get that freedom, our children.

DR. BROWN: Very true. And I, I think this is — there are some heartening playground movements both in Europe and in the U.S., where the playgrounds are going to be not so sterile and allow, I mean, the fact that that there are no teeter-totters and most of the swings don’t really go very far, et cetera, et cetera, and the monkey bars can only be three feet high. You know, it’s reasonable to have safe playgrounds, but it’s also reasonable to have challenging playgrounds. And I think the balance — to develop that balance is a skill that’s now becoming part of architectural schools. And I know there are some corporate interests in Europe that are trying to develop multiethnic playgrounds so that some of the ethnic tensions will be dealt with in a playground way when the kids are small.

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm. I mean, I kind of hear you putting a point on this so — in saying that, you know, that we’re keeping their bodies safe and endangering their souls if we don’t let them take some risks and be more playful.

DR. BROWN: No question about it. I think it’s safer for the person who is a player to take a few hard knocks and maybe have a fracture in childhood, than it is to insulate them from the possibility of that. I think that that constricts their psyches and their futures much more.

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm. You’ve even said that play rewards and directs the living of life in accord with innate talents. How does that work? How do you see that?

Well, I could ask you as a parent and any other parent that’s listening with their young child, you know, say a child over three but under 12. And if you just observe them, and don’t try and direct them, and watch what it is they like to do in play, and get some sense of how their temperament intermixes with their play desires, you often will see a key to their innate talents. And if those talents are given fairly free reign — and this I’ve done through a lot of clinical study of histories of people, you know, some of whom played and some of whom haven’t — if you allow those innate talents to build upon themselves and the environment is favorable enough so that it supports that, then the sense of empowerment and freedom such as a premier musician or a prime athlete that’s joyful in their athleticism or, you know, the writer who’s imaginative — J. K. Rowling, you know — I think that then you see that there is a union between self and talent.

And that this is nature’s way of sort of saying this is who you are and what you are. And I’m sure if you go back and think about both of your children or yourself and go back to your earliest emotion-laden, visual and visceral memories of what really gave you joy, you’ll have some sense of what was natural for you and where your talents lie. So that’s why I write that. I think it’s pretty important.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Do you, um — I think it’s fashionable to say that media is ruining our children and they watch too much TV and video games are ruining them. And it’s certainly one effect of keeping our children safe indoors is that we kind of make them captive to technology. That can be one effect. But I will say that as I look at some of the computer- and Internet-based games that my children discover, some of them are incredibly interactive. And there’s a lot of imagination.

DR. BROWN: Sure, they are.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, is some of that okay?

DR. BROWN: Oh, sure, of course. I mean, the research is not very good, in my field. It is pretty good on the effects of violent TV, for example, the prolonged exposure of violent TV. But, but the research on video games, particularly if it’s kind of non-addictive video game use, is not very solid. And I think there is evidence that a limited amount of video games probably increases imaginativeness and skills. And the newly-designed video games that incorporate movement are likely to be much more savory for the body and mind than, let’s say, one that’s strictly two-dimensional screen and your thumb’s on a gadget.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. Is the involvement of the body generally really important in terms of the positive effects that you’ve noted in play in animals and people?

DR. BROWN: Absolutely. I’m glad you asked the question. Part of the brain called the cerebellum, at least when I went to medical school, was thought to just help coordinate eye movements and body balance. Now, with refined imaging techniques, we see that there are connections between the cerebellum and the prefrontal cortex that get lit up by three-dimensional movement. And there’s every evidence that movement accelerates learning. And this is in its infancy, but there’s enough evidence for this that this is — these are parts of studies that the National Institute for Play is attempting to organize because it seems to be very important.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, you know, I’m struck that we’re having this very serious conversation about play.

DR. BROWN: Well, this is serious, you know? We don’t want to have any mischief happening on this program.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s right. I mean, just tell me how this research, in this immersion that you have in play as a study, how does it change your experience of this part of life? Or how does it change you?

DR. BROWN: Well, I give myself over at least three or four hours a day to what, for an old guy, is spontaneous free play. It, you know, it could be reading or what I would call as extremely low-quality rogue tennis, hiking, playing with grandchildren. But I, you know, if a day goes by and I haven’t, at this age, had some sense of timelessness and freedom and purposelessness, I’ll probably be kind of ratty by suppertime.

MS. TIPPETT: But, boy, cultivating an appreciation for timelessness and purposelessness, I mean, that’s work in our culture.

DR. BROWN: Shouldn’t be. Should be a part of our — and, you know, you attenuate recess, cut down recess and kids are learning that what’s important is academic performance. Whereas, probably equal amounts if not more are being learned on the playground at recess. Most kids are outside of time when they’re on the playground at recess if it’s free play.

MS. TIPPETT: Say some more about that. What do you mean “outside of time”? I mean, that’s such an evocative phrase.

DR. BROWN: Well, if one were to get a replay of Michael Jordan in one of the final games of NBA championship and see him zoning down the floor doing some moves he’s never done before and tossing the ball up for a basket, I doubt if, at that time, he is really conscious that the buzzer’s about to go or that — I think he’s outside of time. And I can certainly give you from my own life recollections of that sensation. Just, say last week, I was I in a nice musical concert that was being held in Monterey and, you know, I got lost in the music and had the feeling of, you know, sort of an oceanic feeling of not being there. And it wasn’t something I expected to happen. But it was pleasurable. Watching a grandson of mine on the floor with his stuffed animal talking to it, timeless. And it’s different for, for lots of us.

But I think that that’s a, you know, a play state of being that’s an important sense of priority that you don’t try and struggle toward, but you try and sort of let it happen to yourself from within what works for you.

[Music: “Mondoline” by Spring String Quartet]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today with Dr. Stuart Brown: exploring the place of play in human spirit and character.

MS. TIPPETT: You did mention reading, and I don’t know if reading would fall into a definition of play, but it is something, for me, that’s a very pleasurable and transports me to a timeless place. Does reading count for you?

DR. BROWN: Oh, of course.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. BROWN: Very much so. And I share that, that same weakness.

MS. TIPPETT: And so, you know, when you talk about timelessness that does have a spiritual resonance. How do you think about the spirituality of play that’s — maybe you would put other words on it.

DR. BROWN: Well, I don’t know that I have a crisp way of thinking about it. I can give you a private experience that was, to me, a spiritual experience.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

DR. BROWN: When I was working with the National Geographic and — was able, privileged to spend time with play researchers in Africa, I do vividly remember one morning when I was watching a pride of lions and two sub-adult female lionesses got up, looked at each other — and there’s a picture of this in the National Geographic magazine, what looked from a distance kind of like a fight, but it was a ballet. And while I was watching this, I was overwhelmed by the feeling that this is — I’m almost brought to tears talking about it now — that this is divine.

There’s something divine going on here that transcends their carnivorousness and the, you know, red and tooth and claw and the rest of it. Now that’s my projection onto it, but it still was very meaningful to me. And I think seeing a young child just immersed in play and watching them closely is a spiritual experience. And there is spirit emerging in play. Something non-material that’s a part of it that at least it’s hard for me to define it as just ions zipping around in a nervous system.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. And, I mean, if you are a religious person, do you have a different image of God because of this?

DR. BROWN: Yes. I do.

MS. TIPPETT: What does it do to your image of God to be a lover of play?

DR. BROWN: Well, I think, you know I’ve got — since I’m — one foot is always stuck in science, I have some sense that this is God’s way of evolving — of things evolving in our biological universe. That some of the driving force behind change, uh, is embodied in these — this emergent property, this self-organizing system that tends to captivate the nervous system and the behavior of humans but — that I call play.

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm.

DR. BROWN: And that for me expands and kind of gives me a sense of unity with time and space and permanence and even the galaxies, which are also self-organizing and emergent.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s a very pleasant way for God to organize self-organization. Through play.

DR. BROWN: Well, there’s also violence and there are a few other things that one sees that I don’t want to be, you know, Pollyannaish about it…

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. BROWN: …because I’ve certainly seen the world in its — you can’t as a psychiatrist or a studier of violence not see the other side.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

DR. BROWN: Which I’ve seen too.

MS. TIPPETT: But this is part of the big picture.

DR. BROWN: Sure is.

MS. TIPPETT: That this is also part of the big picture. I mean we get a lot of publicity of that other — of the violence. Right?

DR. BROWN: I’ll say. I’ll say we do. And it’s there. It’s real, there’s no shrinking from it.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. What would you like to talk about? What have I not asked you about that animates you in this that you want to share with people?

DR. BROWN: Well, I think the sense that, if you’re living a life without it, yeah, your life can go on okay, it’s — you’re gonna survive, you’re not going to die if you don’t play.

MS. TIPPETT: Without it, with play, right. Without play.

DR. BROWN: Without play.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

DR. BROWN: But, uh, it’s kind of an endurance contest or sort of the joy of living is lessened if one doesn’t play. And in particular, if parents are tense and over-organizing their kids with the hope they’ll succeed, get into Princeton, make a lot of money, so that they insist that every moment be playdates or soccer or ballet or gymnastics or, you know, music here, that some of the essence of life is being missed.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

DR. BROWN: And that’s one thing and that’s important to me. And probably, the other thing that we haven’t talked about but which has really struck me since I’ve been a student of play, is looking at the biological design of being human. And when you look closely at that, I’ll give you an analogy. A Labrador retriever plays through its lifetime and dies a child. A wolf sort of gives up childish thing, double scent marks, has alpha behavior, governs its reproduction, and is a very successful animal if it isn’t killed off by humans — but doesn’t play much. But if you look at the human and look at our nervous systems and our, what I would call our physiognomy, the way we look and the way we’re designed…

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. BROWN: …we really are designed to retain immature playful-like attributes throughout our life cycle. That’s a fundamental part of our design. We know that human beings are now capable of neurogenesis, of new neural development throughout the lifetime, whereas most other creatures cannot. That’s a design part of being human. Now take that into policy matters.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

DR. BROWN: Do we parent that way? Do we teach our kids in school that way? Do we take advantage of the design? Do we also see that there are hazards? The permanent adolescence of the human being means we may be subject to irrational, impulsive behavior. Maybe our laws and our institutions should help reflect that a bit more. If we don’t play, what are the consequences? We’re more reptilian. We’re more savage. We’re more — we lack some of those features that I’ve mentioned earlier in the program.

MS. TIPPETT: I think that in making a connection between play and maturity and wisdom, because you know that’s something I hear, you’re affirming — I think one of the most surprising experiences I’ve had of enjoying growing older, you know, sort of heading into the latter part of my 40s, which is that I actually think I am enjoying life more and relaxing, and…

DR. BROWN: Good for you.

MS. TIPPETT: … and throwing myself into play in a way that I didn’t when I was younger and, you know, accomplishing things. Hopefully, I’m still accomplishing things but I’m not…

DR. BROWN: You’ve gained wisdom earlier than most of us. I certainly was a workaholic doctor for too long in my life.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. But I mean that is the model in our culture of what being mature is. I mean, being mature is being that wolf. It’s leaving behind the Labrador behavior. I mean, clearly, I know what you’re saying.

DR. BROWN: Correct.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s a line between being the permanent adolescent and being a playful, mature human being. But, um, I don’t — I think you’re right that our culture doesn’t know how to talk about that playfulness as a wisdom, kind of.

DR. BROWN: There is a kind of a paradox and it doesn’t mean we should be irresponsible.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

DR. BROWN: Just the opposite. By having empathy and trust and compassion, which I think are byproducts of the playful life because you got a little left over, it doesn’t mean that you’re just going to go off and do whatever you want hedonistically. There are boundaries that are certainly part of…

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. BROWN: … play. But it doesn’t mean you have to be a grouch or serious all the time. I mean, look at Reagan and Gorbachev at, uh — talks in Iceland. They broke down completely until the morning they were to leave, Reagan had said, ‘Let’s have breakfast together.’ And he went in, started telling dirty jokes, and then Gorby started telling dirty jokes. They reorganized the conference and they got the missile situation taken care of. So…

MS. TIPPETT: That’s hard to turn into a paradigm, though…

DR. BROWN: Yes, I know. I don’t expect us to do that with the Iranians at the moment.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Yeah. I remember being at a retreat once. I think it was a spiritual retreat, very serious. And I remember some people saying how one of the things they were working at at this point in their life was playing more, and something about the way they said it, about what hard work it was, made it feel like a doomed enterprise. And you know…

DR. BROWN: Well, it doesn’t sound like….

MS. TIPPETT: And I worry a little bit we’ve now kind of rediscovered — we’re having this conversation about our children. But are we going to make them work so hard at playing that we ruin it for them? So, I mean, what advice would you give people about recovering this as a healthy part of our lives if it’s something that we’ve lost, and that our culture really, really works against?

DR. BROWN: I think recovering it depends a little on how much of it you had as a kid and you can bring back in adult form into your current contemporary life. You know, I take a lot of reviews of play of varieties of people. And when I come across somebody who really has had an abusive childhood and they say, ‘Well, I never really played. I never felt free to play.’ It’s not that they’ve lost it. They feel they’ve never had it.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. BROWN: Well, then you start with things like rhythm and movement and those things that intrinsically produce some sense of pleasure and joyfulness. Well, as Bob Fagen says, “Movement fills an empty heart.”

MS. TIPPETT: You mean like movement, dancing or sports or anything?

DR. BROWN: Dancing, yeah. Dancing, but things that are conflict-free but that you can kind of do that produce a sense of some of the things I’ve talked about — a sense of pleasure, of taking you out of that urgency of time — that work for you, whether it’s reading or dancing or hiking or conversation in a pub or what. You know, there are lots of different ways. But I think it’s important to find those things that work for you and to then, as Campbell said, then “follow your bliss.”

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

DR. BROWN: Find your bliss and follow it. But the bliss is usually retrievable. It’s kind of like you have to reach for it and pull it out, you know, from within your memory. But reach into visual images and emotional images that are — that produce a sense of pleasure for you, and then build on them. And that usually helps in the recovery. And it’s not something that happens overnight. It’s a slow but enjoyable process.

MS. TIPPETT: I think it might be frightening at 60 to say this is an absolutely essential part of being human that I’ve paid no attention to and I’m not very good at, and don’t know how to begin.

DR. BROWN: But you know, it’s different than trying to learn a new language, learning Chinese at 60 because Chinese isn’t embedded in you but play is.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. BROWN: You got a leg up on play just by being human.

[Music: “The Biggest Pile of Leaves You Have Ever Seen” by Lullatone]

MS. TIPPETT: Stuart Brown is founder and president of the National Institute for Play near Monterey, California. He is co-author of Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul.

The “Encyclopedia of Play Science,” an online research collaboration between the National Institute of Play and scientists from around the world, will be completed by the end of this summer. Find the link to that research on our website, onbeing.org. And there you can also listen again or share this show with Dr. Stuart Brown. And don’t forget that we also now have a free On Being app. For iPhone and iPad users, go to the iTunes store; Android users, download the mobile app in the Google Play store. Please send us your feedback as we develop the next version.

On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Chris Jones, and Julie Rawe.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.