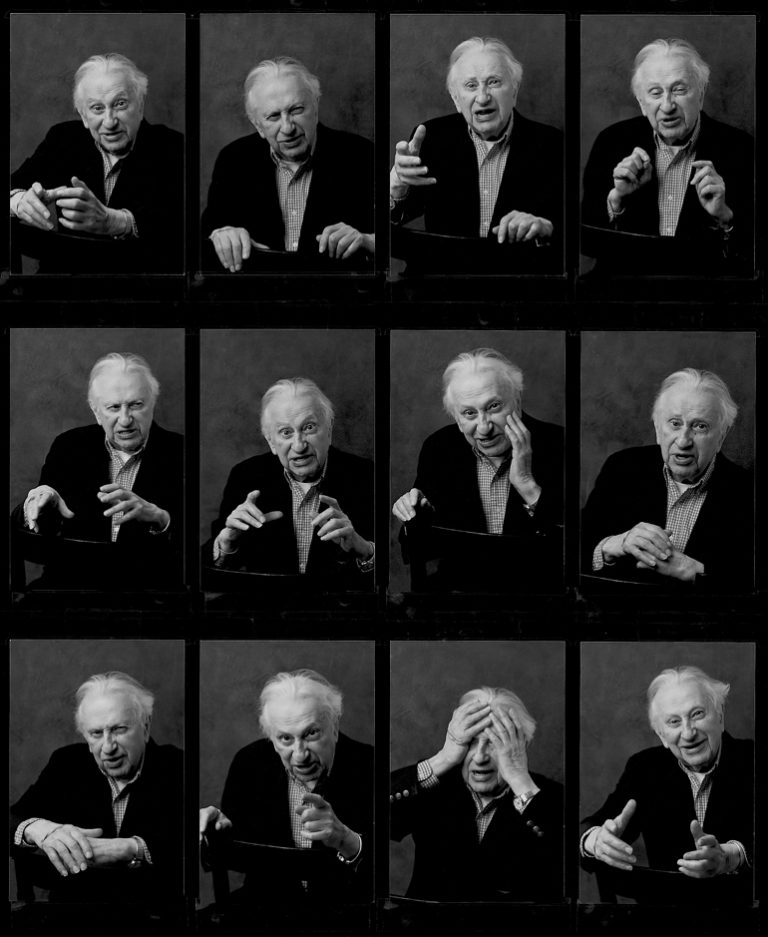

Studs Terkel

Life, Faith, and Death

We remember Studs Terkel, who recently died at the age of 96. The legendary interviewer chronicled decades of ordinary life and tumultuous change in U.S. culture. We visited him in his Chicago home in 2004 and drew out his wisdom and warmth on large existential themes of life and death. A lifelong agnostic, Studs Terkel shared his thoughts on religion as he’d observed it in his conversation partners, in culture, and in his own encounters with loss and mortality.

Image by Nancy Crampton, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Studs Terkel was a radio personality and author who published 20 books on central themes and events in American life. He won a Pulitzer Prize for his 1984 oral history of World War II, The Good War. He died on October 31, 2008.

Transcript

November 13, 2008

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, we remember legendary interviewer Studs Terkel, who chronicled decades of ordinary life and tumultuous change in American culture, until his recent passing at the age of 96. I sat down with Studs Terkel at his Chicago home a few years ago and drew out his wisdom and warmth on large existential themes of life and death. A lifelong agnostic, Studs Terkel also shared his thoughts on religion as he’d observed it in his conversation partners, in our culture, and in his own encounters with loss and mortality.

MR. STUDS TERKEL: I happen to be an agnostic. You know what an agnostic is, don’t you? A cowardly atheist. I, myself, don’t believe in any afterlife. I do believe in this life, and what you do in this life is what it’s all about.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett.

He was called the man who interviews America, a legendary character. This hour, we explore the late Studs Terkel’s accumulated wisdom on the big questions of life, loss, and mortality. A contented agnostic, he believed that taking death seriously means taking life seriously.

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. Today, “Studs Terkel on Life, Faith, and Death.”

Studs Terkel was best known as a Chicago radio personality. He was also a playwright, a sportscaster, and a Pulitzer Prize-winning author. On air and in writing, he chronicled ordinary life and tumultuous change in American culture. He had a deep knowledge of music and the arts, history and politics. Studs Terkel also had a singular gift for inviting others to give voice to their lives, especially what they know and do well.

[Beginning of audio montage of archival interviews by Studs Terkel]

MR. STUDS TERKEL: This morning, we have as our guest the distinguished young American writer — I was about to say novelist, but I realize now his fields are — include more than the novel, Gore Vidal. Mr. Vidal …

David Hockney is without a doubt, the most celebrated of all British painters living today, perhaps of the century.

I’m seated in the gracious apartment of Madame Simone de Beauvoir, 11 bis rue Schoelcher in Paris. I see we’re surrounded by books, typewriter writings …

Mahalia Jackson, my guest this morning. Mahalia, I’m thinking about you and this song, and I’ve known you since about 1946. That’d be about 17 years we’ve known one another, Mahalia.

MS. MAHALIA JACKSON: That’s right.

MR. TERKEL: I think about this song …

Arthur Miller, distinguished American playwright, memoirist and, for that matter, president of Pen, the international writers congress …

But now and then, someone comes along — we’re talking about technology, electronics, music — but someone comes along who’s an original, and Laurie Anderson is definitely an original.

[End of montage]

MS. TIPPETT: When I interviewed Studs Terkel at his home in Chicago, in 2004, he was in recovery from a serious fall. His famous voice was a bit weaker than it use to be, but as full of passion as ever. We met in his dayroom, which was overflowing with books, old and new, many of them written by people he’d interviewed. In one of his most beloved books, Working, Studs Terkel drew Americans out on how they spend their days. So I began our conversation by asking how he’d come to understand the humanizing power of an interview and what was it in his approach, I wondered, that allowed such a range of people not only to open up in his presence, but to achieve an honesty, even a wisdom they had scarcely known in themselves?

MR. TERKEL: You got to start in the beginning. History. The publisher happened to catch some of my interviews of different people. These were known people, like Bertrand Russell or Brando. And he said, ‘How about you doing a book about ordinary people and their lives?’ Because he’d just published a book about China, what happened after the Mao revolution. And he said, ‘Why don’t you do one about an American village, Chicago, in the middle of its own revolution,’ early ’60s, cybernetics and civil rights, the anti-war, the various things. That’s how it began. The ordinary, non-celebrated people. Celebrities, by and large, are a pain in the ass, you know. No, they are because, you know, they say the same things.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. And they’ve said it too many times.

MR. TERKEL: Yeah. They had to push the movie they’re in and push the book they’re in. So that means nothing at all. Now, why’d I choose these people, these certain kinds of people? Now, this applies to all the books. Well, they’re not ordinary people. That is they are, and they’re not.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. So talk to me about what it is that happens in a conversation when it is really special.

MR. TERKEL: There’s no one way. For example, this is my very first book, I was visiting a housing project, and it was mixed. Now, back in the early days, you know, housing projects were quite good, you know, very good, replacing tenements and shacks. And so this woman I’m visiting, and I don’t recall if she’s white or black, she was light skinned. She was very pretty, I know that, skinny, about four little kids running around. They’re excited — mama’s got this thing in front of her. She was never interviewed before. The tape recorder itself was still fairly new. And she’s talking to me. And as she talks, I talk, too, you know. And we become friendly like. And I said something that either angered her or made her feel good, I forget. And then we finished the interview, and I feel kind of good. I got a hunch there’s something here. I don’t know what. I just feel kind of good. But the big thing is those kids, those five-, six-year-old kids jumping around the house. They want to hear mommy’s voice. They know it plays back. And I said, ‘You be quiet now. Now, don’t jump around so much. You be quiet, and I’ll play it back for you.’ And so I’m playing back the voice that she herself never heard before. She never heard herself talking, or in this case, thinking as well as talking. And suddenly she said something on the microphone. She heard, as the kids are dancing around, and she puts her hand to her mouth and “Oh, my God.” And I said, “What?” And she says, “I never knew I felt that way before.” Well, that’s a great moment. She’s saying, “I never knew I felt that way before.” It’s suddenly a discovery she’s made as well as I’m making one. So it’s as though we’re both on a journey in a way. You might say we’re both on a sort of journey.

MS. TIPPETT: And do you think that the presence of another person, of you, the conversation partner, makes that kind of discovery possible?

MR. TERKEL: Well, it would depend who the other person is. Not is, we’re all basically human. What the person has in mind, is it to make the 5:00 news? Is it to say to a mother whose child is dying in her arms, there was a slum fire, ‘How do you feel?’ you know? I’m giving you a horrible example, of course, but it depends what the purpose is. My purpose: What is it makes people tick?

MS. TIPPETT: Studs Terkel, who recently passed away at the age of 96. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. This hour, we’re exploring Studs Terkel’s collected wisdom on faith, life, and death. I interviewed him in 2004 at his Chicago home.

In 2001, Studs Terkel had published the one book he said he never thought he’d write, an oral history of death. He called it Will The Circle Be Unbroken? Reflections on Death, Rebirth, and Hunger for a Faith. Characteristically, he spoke with people from all walks of American culture — doctors, firemen, policemen, gang members, social activists, musicians. Death is not a subject that comes easily, and Studs Terkel found that when given a chance to reflect, most people didn’t experience it as a one-time encounter at the end of life. As he asked people to reflect on the experience of death in their lives, story upon story emerged. They described the deaths of co-workers and neighbors and people close to them, of their own brushes with mortality, of the questions of meaning such experiences always seem to raise. When Studs Terkel began to research that project, he was 86 years old. He had survived a quintuple bypass, and as he put it, “other medical adventures.” And then Ida, his wife of 60 years, died. I asked Studs Terkel whether her death drove that project forward.

MR. TERKEL: Well, I don’t know how to answer that. I mean, did her dying play a role in writing the book? I’m sure it did to some extent, because it was 60 years. We were married 60 years. Well, as you know, she looked quite young, you know. It wasn’t that, the way she felt. ‘Why do I still feel like a girl?’ you know. And so a couple of days before she died, our neighbors across the way, Laura Watson, looked and she sees this girl in, what do they call it, denim things, the Levis, you know.

MS. TIPPETT: Jeans? Yeah.

MR. TERKEL: Sees this girl with a daisy in her hair, plucking the weeds out of the garden. ‘Who’s that girl? Oh, my God, it’s Ida,’ you know, who was 87 at the time. Well, in any event, did that play a role? It’s hard to answer. Well, that was a book that was a revelation to me as well. Remember that I’ve hit various aspects — the Great American Depression, history, World War II, working, jobs people do, race, black and white, growing old aged us, all variety of aspects. What haven’t we touched along the line? Death. How do you talk about death? And then my wife died. It hit me. Of course, I’d play a lot of folk music and other stuff. Among them was “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” And “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” as you know, is a very familiar folk tune the Carter Family sang, although others wrote it, you know. That song, of course, deals with mortality, immortality, and family. Family, of course — will the circle be unbroken? And the inference is, no, it will not be, bad English, unbroken. And that’s more or less how it came about.

[Audio clip of “Can the Circle Be Unbroken”]

MS. TIPPETT: One of the people who I recall most vividly from Will the Circle Be Unbroken? was the man who’d spent years on death row on false —

MR. TERKEL: Oh, I just got a letter from him the other day, Delbert Tibbs.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, and I think, yeah, Delbert Tibbs. He was one of the most articulate and wise —

MR. TERKEL: Delbert Tibbs. I meet him — how did I meet him?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. How did you find him?

MR. TERKEL: Through friends, friends. There’s a committee to fight the death penalty, and Rob Warden is one of the guys I know. He says, ‘You got to meet this guy, Delbert Tibbs,’ who’s now being freed, because he was obviously innocent, the DNA, everything else. But he’s a black guy, hitting the road. He likes to hit the road a lot, who by the way, reads scripture a lot. He’s religious, but he’s also a skeptic.

MS. TIPPETT: And he’s eclectically religious …

MR. TERKEL: He’s very eclectic.

MS. TIPPETT: … to use your word, yeah.

MR. TERKEL: He brushes up on the Qur’an and the Talmud.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, the Buddha.

MR. TERKEL: But mostly, his articulateness — not his articulateness, his — the sense of goodness about him, doesn’t — he looks like your sharpie. He looks perfect, you know? Skinny, moustache, hot shot. But precisely the opposite, you see. Well, you found him quite moving.

MS. TIPPETT: Here’s a passage from Studs Terkel’s book Will the Circle Be Unbroken? It’s an excerpt of his interview with the former death row inmate Delbert Tibbs. Tibbs murder conviction was overturned for lack of evidence, but only after he had spent two years on Florida’s death row.

READER: When I meet people now, if they try to make a big deal about me having been on death row, I sometimes gently remind them that we’re all on death row. The difference is that here the state’s going to do it, and at some point you’re going to know the date and the hour, but that’s the only difference.

I believe life is endless. We can’t talk about life without talking about death. We can’t talk about death without talking about life. I was listening to the Dalai Lama. I read his autobiography, and he says that Buddhists often meditate on death. That’s total anathema to the Western mind, right? I think it has something to do with Greek culture, with its bifurcation of existence — this is life and this is death. I learned to meditate before I went to death row. That’s one of the things that helped me get through, but it was very difficult.

What I’ve discovered is all of the holy books are marvelous, absolutely so, including the Bible. The Bible has the most beautiful language of any book I’ve ever read, not to mention the fact that there’s something there. God is there. But I really do believe he’s hidden. I believe the Jewish mystics who went into the Kabbalah know that. The Bhagavad Gita is the bible to 300 million Indians and others who are not Indians. Thoreau and Emerson read it. Krishna says there never was a time when you and I did not exist, and there will never be a time when we cease to be. He said, ‘This body wears out, like garments, and when a garment wears out, you take it off and you lay it down and you pick up another one and put it on.’

One of the terrible things about executions is to jump people off into the universe like that. I think for a soul to be wrenched from the body is for the soul to be in anger and in pain and in hatred. I believe it impacts negatively on our world, that probably a lot of the calamities that happen are a result of that sort of thing. I mourn for the whole world, because it’s such a horrible place so often.

MS. TIPPETT: From Studs Terkel’s interview with former death row inmate Delbert Tibbs, quoted in his book Will the Circle Be Unbroken?

MS. TIPPETT: So, you know, one thing that is very striking that I didn’t expect is that — your book about death, it’s really a very religious book.

MR. TERKEL: Religious book?

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. I mean, there’s a lot of religion in it, all the way through it. I mean, did you know that, that those themes would be so prominent when you started it?

MR. TERKEL: Well, I knew religion would play a role in it when I — to be fair, I happen to be an agnostic. You know what an agnostic is, don’t you?

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, yeah.

MR. TERKEL: A cowardly atheist. And I’m an agnostic. But religion — well, you know who the most religious people in the country are? Black people, by far. Do you know who Gary Wills is?

MS. TIPPETT: Uh-huh.

MR. TERKEL: Gary Wills wrote — one of his books is one of the least known. It’s called Under God: Religion and America. And it’s mostly — well, it’s about African-Americans and the church. My friend who died recently, Vernon Jarrett, was a black journalist. And Vern is nonreligious, but he felt the importance of religion when his son died. And he thought how important it was, that church, with all the ritual, with all the hours, it was Episcopalian, black Episcopalian, but it was as long as a Catholic ceremony.

MS. TIPPETT: High Church, probably.

MR. TERKEL: Yeah, is was High Church.

MS. TIPPETT: Anglo-Catholic, yeah.

MR. TERKEL: And it was forever ever and ever. But it gave him solace. So in that sense, without being philosophical, in that sense, the word is “faith.” You’ve got faith. In other words, faith and religion are one and entwined so often. Well, I have faith my ball team is going to win. I have faith we’ll win that lottery. But mostly tied up with God or with religion, faith, in that sense. And so religion played a tremendous role in the book. Well, it had to. It’s hard to separate the two.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. I think what your book chronicles is actually the way people live with religious ideas. And it’s so much about asking questions, right, rather than having answers.

MR. TERKEL: That’s right.

MS. TIPPETT: But it’s woven all the way through these people’s reflections.

MR. TERKEL: It’s all through it. In fact, I mentioned Vern. He says — Vern Jarrett — he said, ‘I never dreamed I’d want to be in that number when the saints go marching in,’ and that music in the background. And he’s, ‘And yet I needed that,’ you see? ‘I needed that.’ And so the expression of religion, in the true sense of faith, belief — since science and medicine said no, despite all the advances, the last stage of cancer, no, there’s something.

MS. TIPPETT: The late Studs Terkel. This reading comes from Studs Terkel’s interview about death and faith with his friend, the late Vernon Jarrett, a former Chicago Tribune columnist. It is in Vernon Jarrett’s words.

READER: I took a vow at my father’s coffin that I had to do something with my life as a perpetuation of his. That’s what I think really counts the most. I’m doing the same thing with my son. Much of what I do is on behalf of my son. I do a lot of volunteer stuff with kids, and it’s really in his memory.

I wish I were wrong about my doubts, that I’d never, never, never see my son again.

I have a tombstone. I want my name on it. I want to be buried next to my son. There’s an old black spiritual that says, “This little light of mine, I’m going to let it shine.” Right now. Since we don’t know the truth about any of this, you better let your light shine right now.

[Audio clip of “This Little Light of Mine”]

MS. TIPPETT: From Studs Terkel’s book Will the Circle Be Unbroken? Reflections on Death, Rebirth, and Hunger for a Faith.

We’ve reprinted the entire interviews with Vernon Jarrett and Delbert Tibbs, as well as conversations Studs Terkel had with a Hiroshima survivor, writer Kurt Vonnegut, and the actress Uta Hagen. Read them on our Web site, speakingoffaith.org. Studs Terkel’s passing gave us a chance to remember our time with this iconic American figure. For one of my producers, it was the sip of whiskey he didn’t drink with him. You can read Trent’s recollection on our blog, SOF Observed. For me, it was a chance to listen to that original conversation in Studs Terkel’s Chicago home, nearly four years ago. He was 92 then, but he still had the same energy, warmth, and curiosity that he had brought to the many interviews he conducted over the years. We wanted to share this complete unedited exchange with you. Download an MP3 of that full conversation and the program you’re listening to now. They’re both free. Get them on our Web site, podcast, and e-mail newsletter, all at speakingoffaith.org. And after a short break, more of Studs Terkel’s reflections on how thinking about death means thinking about life. Also, his thoughts on how the idea of death changed in our culture and for our children during his lifetime that spanned nearly a century.

I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, we remember, Studs Terkel, who died recently at the age of 96. I sat down with him in his Chicago home when he was 92 and drew out his wisdom and warmth on the large existential themes of faith, life, and death. Studs Terkel was a renowned conversationalist, a playwright, disc jockey, and sportscaster. He was best known as a Chicago radio personality, and for his award-winning books that chronicle ordinary life and tumultuous change in the 20th-century world. Here’s Studs Terkel in 1962, introducing an interview taped in Wales with the British philosopher Bertrand Russell.

[Beginning of excerpt of Bertrand Russell interview]

MR. TERKEL: I’m seated in a very delightful room facing the mountains and the scene is so peaceful. I hope my pronunciation of the Welsh city is right, Penrhyndeudraeth. On this very lovely and peaceful Tuesday morning, I’m seated opposite the distinguished, the eminent British philosopher Lord Bertrand Russell.

And, Lord Russell, you’re seated here in front of the fireplace. The scene seems so peaceful, and yet the world outside seems so rife with tension — East, West, one accusing the other of being the villain of the peace and proclaiming himself the hero. Let me ask you a leading question, Lord Russell. On which side are you in this nuclear contest?

LORD BERTRAND RUSSELL: Lord BERTRAND RUSSELL: I’m not on either side. I think the contest is folly, and what I …

[End of excerpt]

MS. TIPPETT: Studs Terkel continued to interview and write prolifically well into his 10th decade. He published four books in his 90s. The first, Hope Dies Last, was about people he called crazy in a celestial way, who sacrifice themselves physically and often economically for the good of others. His final two works included a memoir and P.S.: Further Thoughts from a Lifetime of Listening, which is just being published this month. In our conversation, I drew Studs Terkel out primarily on the themes of his 2001 book, which he called an oral history of death. He called that work Will the Circle Be Unbroken? Reflections on Death, Rebirth, and Hunger for a Faith. Studs Terkel carefully distinguished between the words “religion” and “faith,” and told me about the complex relationship he had to both in his life.

MR. TERKEL: Faith is used, of course, in phony terms. There was a movie years ago called The Faith Healer. And, now, faith healers, who are con artists, we know that, play upon the superstitions of people, religion as the faint hopes of people. That’s The Faith Healer. At the same time, someone will tell you that faith healers have their own kind of an effect sometimes. But religion and — see, the word “faith,” your series is called Faith. This book happens to fit right into it, because it’s all about faith. And there are people who are nonreligious here and there. Kurt Vonnegut is in the book.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. I’ve just been reading his books, and I was so happy to see him in there.

MR. TERKEL: He’s called a secular humanist. Well, to him it’s another thing entirely. To him it’s the big sleep.

MS. TIPPETT: But you wrote in the prologue to the book, you wrote, “Everything about this book became unexpectedly for me a journey into long-suppressed memories and all sorts of ambivalences in feeling of which I wasn’t aware.” Tell me about some of those ambivalences of feeling.

MR. TERKEL: I don’t know how to describe that. Right now, see, I got this accident that changed my whole life, obviously, see? Before, I’d describe myself as an elderly man of some vigor. Now I’m just an old, old man, you see? And I’m 92. That’s a pretty long …

MS. TIPPETT: That’s impressive.

MR. TERKEL: … and a rather fruitful life — a number of books, documentaries, and programs. It’s pretty full. So I don’t — and I’m not lying about this — I don’t feel that. In fact, after the accident occurred, and I was in pretty bad shape, and I said, ‘I don’t mind kicking off. I’d like to finish this book. And so if I were to die in my sleep, I wouldn’t feel that lost. I mean, I wouldn’t feel that cheated at this stage of the game. So that’s pretty good.’ Now, how I would have felt 20 years ago is something else.

MS. TIPPETT: How you would have felt …

MR. TERKEL: But even now …

MS. TIPPETT: … about faith or about writing this book?

MR. TERKEL: Even now, why am I here with my caregiver friend, you see? Why am I here if I want — I don’t want to die. Do I welcome death? Well, of course not. Would I like to live it out to see that? Yeah. Would I like to get better? Sure. Maybe there is a slight, but I can walk around with a cane now. I couldn’t before. Have an appetite, I couldn’t before. At the same time, not the same person. And so I still fight death. I don’t welcome it, no. Do I fear it? That’s a good — and here’s where the truth and honesty come in. I’ll probably lie, you see. I guess so. Well, in the first place, you have friends. Many of them are younger, and I don’t want — I’m getting a kick out of things. At the same time, this daily having to have help now and then, yeah, I find humiliating. And so to me death does not mean the same thing as it would to you or to your contemporaries.

MS. TIPPETT: It’s interesting. As you say, when you set out to do this project, you were asking people to talk about the thing we never talk about, and most of us don’t even like to think about, and I even found it hard to approach reading the book. But when people start talking about death and, as you’re doing now, you actually start talking about life.

MR. TERKEL: You see, now you’re coming. You see, you’re pretty good. Now you come to the key to it, of course. How can you separate death from life? So the important thing about death is life. Because it’s the end of something of which you are conscious and aware and, after some slight extent, well, not much, unfortunately, at this moment, you know. Now, what have you done with your life, you see? Now comes the evangelical part. Now comes the preaching part. I’m always doing that, because the books are political by nature, all my books are, because I think life is political. What you do during the time in your life? By the way, it’s a book of many regrets. Things you did not do or perhaps should have done, especially, in many cases, to people close to you. That’s a big one, too.

MS. TIPPETT: The late Studs Terkel, talking about his book Will the Circle Be Unbroken? Reflections on Death, Rebirth, and Hunger for a Faith.

MS. TIPPETT: Something else that people in the book always talk about, or it seems like they all talk about it, even if they’re atheist, is the afterlife, if there is one or if they’ve had to struggle with the question and answer it in some way. You called yourself an agnostic, so what does an agnostic do with the afterlife?

MR. TERKEL: Yeah. Well, I don’t know. For me, well, I want to be cremated, of course. Those are my wife’s ashes on the windowsill next to the daisies, which have got to be fresh daisies, which were her favorite flowers. And I want my ashes mixed with hers and spread over Bughouse Square. You got to know what Bughouse Square is. Well, it’s like Hyde Park in London. You’ve heard of that? The famous speech corner, people talk about everything. Oh, the subject often, for years, was India. And now it’s the Middle East, of course. And so it’s Bughouse Square in Chicago. Unfortunately, nobody goes there now. It used to be full of hundreds of people round and about, and there were speeches and they were funny and wonderful. And there were hecklers and the hat was passed. So I’ll have the ashes strewn around Bughouse Square. And if a lawyer tells me that it’s against the ordinance to do it, I’ll say, ‘Well, it’s been done. Let them sue the ground, or whatever it is, to get it back.’

MS. TIPPETT: Why do you want your ashes scattered there?

MR. TERKEL: Well, because I was a kid and used to go there. It’s right next to the Newberry Library, a big library in Chicago. And I used to go to the Newberry Library and read something on a Friday. And then at 6:00, I’d come out and all the guys had gathered soapboxes. And it was very exciting.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Is that where you learned to love talking, do you think?

MR. TERKEL: Well, talking, of course, and heckling back and forth. You asked about the afterlife. Well, I can’t take bets on it. Who’s going to take my bet, you know? I, myself, don’t believe in any afterlife. I do believe in this life, and what you do in this life is what it’s all about.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, one thing that struck me when I was thinking about — you were born the year the Titanic went down.

MR. TERKEL: Oh, yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, that’s so vivid. And also, you talk about being a child with asthma. Lots of children have asthma now, but it’s not generally life-threatening. And, you know, the girl next door who died of scarlet fever, it struck me that death maybe, in earlier generations in this country, was closer for a lot of children.

MR. TERKEL: Well, you know something? That’s an interesting point. That never came up. I mean, I could have brought that up somewhere in the book. That’s a good point. You see, there’d be signs on the doors, like the girl, the family below us, on the fifth floor or the fourth floor, third floor, and it said “Scarlet fever, beware,” you see? And she died of scarlet fever. She was about eight. But this matter of our kids acquainted with the idea of it earlier, and yet we have more and more, thanks to TV and thanks to technology, we have everything. In fact, you see, I have this theory about, nothing unusual about it, there’s always a gun, and often it’s a girl detective, right, holding the gun. But the gun, they shoot as often as the guys do. And so there’s the awareness of that death, which is of utter meaninglessness. But the personal aspects of death, of the neighbor child, you see, that is something else.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. I mean, I was going to ask you if, in your lifetime, death had changed in the way people think about it. You just pointed to how, in fact, we’ve put death all around ourselves again in another form, in fiction.

MR. TERKEL: Yeah, that’s true. You see, we make death suddenly have no meaning. And by death having no meaning, life has no meaning. I mean, you can’t separate death and life. Death means the end, that’s it. And as to whether there’s an afterlife or not, that’s for each one to choose. By the way, I don’t mock anybody.

MS. TIPPETT: I know.

MR. TERKEL: I mean, if someone — so many speaking of afterlives, and you don’t fault them for that, the belief, the need. But the big thing is are kids aware of death, its meaning today? They see more of it, phony, ersatz death. Right now, we see about five shows right now. And the death of who? And so one American knocks out 10 of them.

MS. TIPPETT: Oral historian and longtime radio personality Studs Terkel, who died recently at the age of 96. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media.

I sat down with Studs Terkel, at his home in Chicago, in 2004, and spoke with him about the big questions of life, faith, and death.

Let me ask you this. You interviewed people who’d encountered death in many different kinds of contexts and circumstances — in war, through illness, the woman who survived Hiroshima, who was there during the bombing.

MR. TERKEL: Tammy.

MS. TIPPETT: She talked about that that was death without dignity. And I wonder if you found people to speak differently about the meaning of death and life, depending on the circumstance in which they encountered?

MR. TERKEL: Well, there again, you see, Tammy, you’re talking about, the Japanese woman who is now a hospital aide, a psychiatric aide working on life. And …

MS. TIPPETT: She was a little girl.

MR. TERKEL: … but hers was so overwhelming. Hundreds of thousands all over her. It wasn’t a question of a single death. It was looking for her mother, hoping she could hear that familiar song that her mother sang.

MS. TIPPETT: Studs Terkel interviewed Tammy Snider in 1997. On August 6th, 1945, the day her hometown of Hiroshima was bombed, she was 10 years old and she was home alone.

[Beginning of excerpt from Terkel’s interview of Hideko Tamura Snider]

MR. TERKEL: I’ve been talking to Hideko Tamura, Hideko Tamura Snider now, and One Sunny Day is her memoir, of course, that day being August 6th, 1945. And so here’s this girl searching the through — looking for — you’re going to the village and you’re asking, ‘Is Mrs. Kamiko Tamura here?’ You’re asking people that. By the way, aren’t you — weren’t you calling out a song, too, that your mother …

MS. TAMMY SNIDER: Well, I got to the point where I thought I cannot bear this anymore. And then so, of course, the last resort for me was prayer. And I say, ‘God, please help my mother, because I can’t find her and I cannot help her.’ And every time I called out my mother’s name, I was saying, ‘Oh, I hope I don’t really find her here. Everybody looks terrible,’ you know. So I started to hum some of the songs that she used to love to sing to me, and I said, you know, ‘God, please carry this tune, if you could, and comfort her, because I can’t be there. But maybe you could.’

MR. TERKEL: Do you remember one of those?

MS. SNIDER: [Sings in Japanese] Something like that, you know? I didn’t know you were going to ask me. I just kind of remember.

MR. TERKEL: You know, that’s beautiful.

MS. SNIDER: And that was one of her most favorite songs she used to sing aloud. So I wanted that song, also, you know, to hum back to her.

MR. TERKEL: Yeah.

MS. SNIDER: Yeah.

[End of excerpt]

MR. TERKEL: Well, I can’t talk for others, even though I put forth this book, still can’t talk for others and their feelings about it.

MS. TIPPETT: But did you hear common themes that surprised you or differences that surprised you? You know, the things that came up again and again that there were echoes of?

MR. TERKEL: Well, faith, as you’d think, well, faith, also, could equal desperation, you see? There’s that, too. I say faith. I say, ‘What’s it called?’ There’s no hope. There’s no hope for that someone who’s so close to you. Well, to someone who’s agnostic, there’s envy of the person who has faith, because at least they have that. That solace. You wish your were, well, the word isn’t innocent, yeah, as innocent — I was going to say naive. That’s presumptuous of me to say that.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. But beyond the solace, I mean, I wonder if you changed your way of thinking about faith or if it got larger in any way?

MR. TERKEL: Oh, well, did I?

MS. TIPPETT: Aside from that?

MR. TERKEL: I don’t know. I’ll have to stick with that for a while. I’m too soon. Also, with my own accident.

MS. TIPPETT: Did it make you ask any questions about faith that you hadn’t asked before?

MR. TERKEL: Oh, yeah. Well, it made me understand. It made me understand the power that it has, whether it’s real or not. But the power that you think it has, it does have that. And you also understand why people are so religious out of despair. Faith comes out of hope. It also comes out of despair.

MS. TIPPETT: And what about these people you’ve interviewed in Hope Dies Last, people who’ve really given themselves over to good and to helping others? Was faith a theme, an echo in that book?

MR. TERKEL: Well, there are certain kinds of people who have put themselves out on the line. Those I call the crazy people, who put themselves out on a line. Some are known, most are not known. But they’re the ones who are out in their way to try to make this a, using the phrase, “a better world,” which of course causes snicker and a laugh these days, you see? By the way, a good number of them have their own doubts, too. There’s still that feeling that there’s something within people not yet tapped. It’s about possibilities within people, basically. But it’s mostly about life.’

MS. TIPPETT: Again.

MR. TERKEL: We come back. The book is not about death. A book about death? I said, ‘No, it’s about life, man.’

MS. TIPPETT: I want to read this. This was from Uta Hagen, the actress. She’s not a religious person, I think, from the interview you did with her, but maybe more of the people in that book are. But she does have this definition of faith that creeps in. “Faith, the miracle of creation, is what a human being is capable of communicating. It’s not a private thing; it has to be communicated.” She goes on to say, “which is what I love about art that you pass on. You enlighten people, you make them laugh, you make them cry. These are the things that make our life worth living. To me, that’s art. That’s my religion.”

I thought of, actually, when I read that about the work you’ve done and how you’ve spent your life listening and talking and helping people bring these things into words — turn them into words, and I wondered what you thought of that, those words.

MR. TERKEL: Well, that’s wonderful. Of course, quoting Uta Hagen. She was, you know, remember, that’s an actress talking. Not just an actress, a great actress. She’s really talking about art, you see.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, but she’s talking about communicating writ large.

MR. TERKEL: Yeah, and communicating. You see, I open her — remember, I opened with the aria from Tosca, “Vissi d’arte.” You know, when Tosca pleads with this police chief to leave her alone, that her life is for love and art. And art. And the idea is art is long and life is short, you know. That’s a nice ending. Thank you very much.

MS. TIPPETT: Thank you so much.

[Audio of “Vissi d’arte, vissi d’amore”]

MS. TIPPETT: Studs Terkel died on October 31, 2008, at his home in Chicago. He was 96 years old. His final book, P.S.: Further Thoughts from a Lifetime of Listening, has just been published. That book includes transcripts from Studs Terkel’s documentary of Voices from the Great Depression. In it’s preface, he writes this: “The situation then was not too removed from the one we face today in the matter of joblessness and need. Today, we use euphemisms, instead of depression we say recession, but to the man and woman designated out of work, one is a synonym for the other.”

You can read excerpts and hear recordings for Terkel’s oral history on the Great Depression on our Web site, speakingoffaith.org. We’re also looking for fresh thinking and language for talking about the current economic crisis. What has happened and why, not just in terms of financial tools and strategies but in terms of personal conscience and values. And we’re starting a dialogue with wise thinkers in the realms of business, education, philosophy, science, and religion. We’ll be posting these conversations on our staff blog, SOF Observed. Learn more and share your stories at speakingoffaith.org.

The senior producer of Speaking of Faith is Mitch Hanley, with producers Colleen Scheck, Shiraz Janjua, and Rob McGinley Myers, with assistance from Amara Hark-Weber. Our online editor is Trent Gilliss, with Web producer Andrew Dayton. Special thanks for this program go to Tony Judge and to the Chicago Historical Society. Kate Moos is the managing producer of Speaking of Faith, and I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.