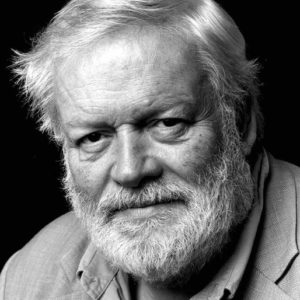

Michael Longley

The Vitality of Ordinary Things

To reassert the liveliness of ordinary things, precisely in the face of what is hardest and most broken in life and society — this has been Michael Longley’s gift as one of Northern Ireland’s foremost living poets. He is known, in part, as a poet of “the Troubles” — the violent 30-year conflict between Protestants and Catholics, English and Irish. And he is a gentle voice for all of us now, wise and winsome about the everyday, never-finished work of social healing.

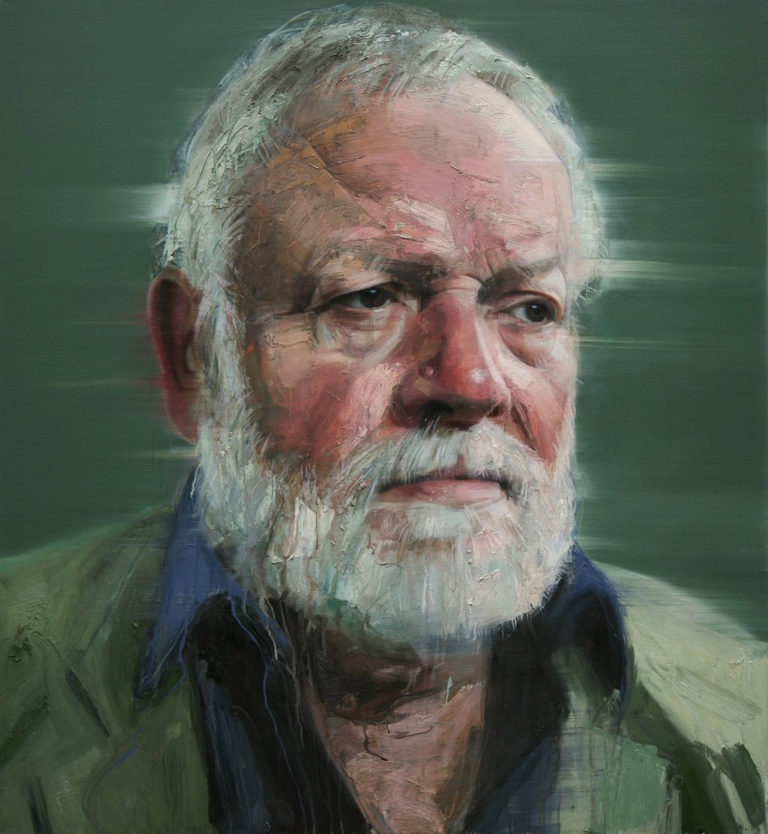

Image by Colin Davidson, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Michael Longley has written more than 20 books of poetry including Collected Poems, Gorse Fires, The Stairwell and his most recent collection, The Candlelight Master. He was the professor of poetry for Ireland from 2007 to 2010 and is a winner of the T.S. Eliot Prize and the Hawthornden Prize. He was also the international winner of the 2015 Griffin Poetry Prize — and that same year was honored with the Freedom of the City of Belfast.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: To dwell on beauty and normalcy, to reassert the liveliness of ordinary things, precisely in the face of what is hardest and most broken in society — this has been Michael Longley’s gift to Northern Ireland as one of its foremost living poets. I had the pleasure of conversing with him before an adoring audience at the MAC Theatre in Belfast, in 2016. Like his late friend Seamus Heaney, Michael Longley was known in part as a poet of what is called “the Troubles” — the bloody, 30-year conflict between Protestants and Catholics, English and Irish. That ended with the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. And to this day, Michael Longley is a gentle, winsome force for us all, in the ongoing, never-finished work of social healing.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

Michael Longley: There’s a line by John Clare that I adore — I love John Clare; I revere him — “Poets love nature and themselves are love.” And I believe that with all my heart. And part of writing is adoration. For me, celebrating the wildflowers or the birds is like a kind of worship.

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

Michael Longley has published over 20 books of poetry. He was born to English parents who moved to Belfast at the outbreak of World War II and raised him agnostic in the midst of Ireland’s religion-centric divides. He describes himself now as a “sentimental disbeliever.”

One thing I was really aware of as we were preparing to come here, and I was preparing to speak with you, is that this is a place that in recent memory has moved away from sectarianism, however humanly and fitfully that happens. And we’re at this moment where it feels like much of the rest of the world is drawing towards sectarianism. So I believe that some of what you know here the rest of us need to know. And a piece of that is the importance of letting the voices of poets rise in the midst of tumult and be part of our way of finding our way back to the possibility of lived peace, and finding out what that can mean.

Longley: My wife used to say that she hoped Northern Ireland would become like the rest of the world, and she now points out that the rest of the world is becoming as Northern Ireland used to be. And compared with what Belfast was like ten years ago, the place is unrecognizable. And I’m rather proud. It’s very incomplete and very imperfect, but we’re getting there.

Tippett: So I always begin my conversations, whoever I’m speaking with, whether they are a scientist or a theologian or a poet, by inquiring about the religious or spiritual background of someone’s childhood. And that kind of takes us right into the dynamics here. And it’s a question that I understand has a special intensity and layers of meaning for somebody who was born in a Protestant household of English parents in South Belfast.

But when I think of the spiritual background of one’s childhood, I think there’s more to that than religion. I see how much you have thought about and written about your father’s time as a — I think you say a “boy soldier” in the trenches of the Great War. And you’ve written that he — when you were growing up, he would scream in his sleep. He was having traumatic memories. And to me, that also feels like part of what would’ve colored your sense of the world, its morality, its safety.

Longley: Well, the mystery of his survival. He joined up as a boy soldier in 1914, and he survived to the end of the war, where the survivor rate was about three weeks, at certain times. So that’s a mystery to me, that he survived and that I’m here.

I do believe in the transcendental. I believe that poetry and art, without a transcendental element, doesn’t really exist for me. And it is slightly sentimental, as you quote me saying. I mean, once every four or five years, I take communion, and I believe in the poetry of it — the poetry of it. And I’m interested in Jesus as a revolutionary poet; as a proto-socialist. And the Sermon on the Mount, the Beatitudes, are as good a system to live by as any that I can think of, and I love them. I love them.

Tippett: I think this is something you’ve said, that “Poetry is about all of the things that happen to people. War is one of them.” Did you say that? I always get nervous about quoting things people said to journalists. Does that sound like you?

Longley: I don’t mind you quoting that. I mean, you may quote some rubbish later on.

Tippett: [laughs] OK. You call me out if I do. I mean, it seems to me you became one of the people who people would call one of the poets of the Troubles. And that was what was happening to people.

Longley: Yes. The poets of my generation, Heaney and Mahon and Simmons, we were very cautious. There was a kind of pressure. During the Second World War, people said, “Where are the war poets?” And a cry similar to that went up here. And I’ve written somewhere that a poet is not like some super reporter; that the raw material of experience has to settle to a new depth, an imaginative depth, where it can then come out as true art.

And there was an awful lot of what we call “Troubles trash” — dreadful novels and execrable poems. And we avoided that; my friends and, I’d like to think, I, avoided that. And the poems eventually came. There’s a lovely poem by Mahon, called “Afterlives.” There’s a beautiful poem by Heaney, called “Casualty.” And these are immortal poems that were born out of our conflict.

And I remember in ‘94, there were rumors that there was going to be an IRA ceasefire. And I was reading the Iliad, which is the greatest poem about war and death and suffering. And there’s this wonderful passage in it where the old king of Troy, Priam, goes to the tent, plucks up courage, goes to the tent of Achilles to beg for the body of Hector, his son, whom Achilles has killed, and Achilles is mutilating the body, dragging him after his chariot. And Priam visits Achilles and begs for the body of Hector. And it, for me, is the soul of this great work of art, the first great and probably still the greatest poem in European literature. And I thought, wouldn’t it be marvelous — this was August, ‘94 — wouldn’t it be wonderful if I could compress this quite long episode into something like a sonnet and make my own contribution to the peace process, as we called it. And this poem emerged. It’s probably my best known poem.

Tippett: “Ceasefire,” right?

Longley: Should I read it?

Tippett: Yes, please do.

Longley: “Ceasefire.”

“I

“Put in mind of his own father and moved to tears

Achilles took him by the hand and pushed the old king

Gently away, but Priam curled up at his feet and

Wept with him until their sadness filled the building.

“II

“Taking Hector’s corpse into his own hands Achilles

Made sure it was washed and, for the old king’s sake,

Laid out in uniform, ready for Priam to carry

Wrapped like a present home to Troy at daybreak.

“III

“When they had eaten together, it pleased them both

To stare at each other’s beauty as lovers might,

Achilles built like a god, Priam good-looking still

And full of conversation, who earlier had sighed:

“IV

“‘I get down on my knees and do what must be done

And kiss Achilles’ hand, the killer of my son.’”

Now, that appeared then in The Irish Times, the week of the ceasefire. And I was walking down the Lisburn Road, and a man came up to me and he said, “I really admired” — he called it my “Achilles poem.” He said, “I really admired your Achilles poem, but I’m not ready for it. My son was the victim earlier this year of a punishment beating. I’m not ready to forgive.” And I wondered to myself, was this poem of mine premature?

When I wrote it, there was a wonderful guy in Enniskillen, called Gordon Wilson. He was a draper, and he was blown up beside his daughter at the Enniskillen atrocity on Remembrance Day. And a couple of days later, with his arm in a sling and plaster on his face, he said to the television cameras that he forgave the killers of his daughter. Didn’t even call them murderers.

And I had his face in my mind for Priam, when I wrote that poem, that not everybody could behave with the extraordinary, almost superhuman magnanimity of Gordon Wilson. And I thought perhaps my poem might have been premature, that it might have been too symmetrical and neat and tidy. So I wrote a kind of awkward, gauche corollary to “Ceasefire.” And I’ll read that one.

This is “All Of These People.” And it’s really my message to the world. It’s in the first line; in the first couple of lines.

“Who was it who suggested that the opposite of war

Is not so much peace as civilization? He knew

Our assassinated Catholic greengrocer who died

At Christmas in the arms of our Methodist minister,

And our ice-cream man whose continuing requiem

Is the twenty-one flavours children have by heart.

Our cobbler mends shoes for everybody; our butcher

Blends into his best sausages leeks, garlic, honey;

Our cornershop sells everything from bread to kindling.

Who can bring peace to people who are not civilized?

All of these people, alive or dead, are civilized.”

[music: “Dún Do Shúll” by Caoimhín Ó Raghallaigh]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today with the great Northern Irish poet Michael Longley in front of a live audience at The MAC theater in Belfast.

[music: “Dún Do Shúll” by Caoimhín Ó Raghallaigh]

It seems to me that the distinctive place that you carved out for a poetic voice, an artistic voice in the midst of this atrocity, was this quiet insistence on celebrating normalcy, and noting normalcy and the persistence of human activities in life in all its aspects, including the garlic — the enlivening details that remained.

Longley: Well, have you read any concentration camp literature? The greatest book of the last century, for me, is Primo Levi. And in that kind of nightmare, what kept people sane was thinking of the ordinary things back home. What made things slightly less nightmarish would be securing a toothbrush, or woman’s things, for sanitary purposes. And sanity itself depends on these banal, commonplace little things. No doubt about that.

Tippett: I think “The Ice-Cream Man” is another beloved poem of yours. And would you read that one?

Longley: Yes.

Tippett: Which — to that point that you just made.

Longley: This was a man called Seymour, and he was murdered on the Lisburn Road. And I had been botanizing in the beautiful part of County Mayo, looking for wild orchids. And as a little exercise, I put in a little green notebook in my pocket all the flowers I’d seen in one day. And I came back, and this awful thing had happened. And my younger daughter, who was a regular customer and knew all the ice cream flavors by heart, she told me the news and that she had used her pocket money to buy a bunch of carnations to lay on the pavement outside.

And what I did, I almost sleep-walked into this poem. I made a kind of pattern of the flower names in my book, and I made a kind of a metaphorical wreath of the flower names. And the poem’s addressed to Sarah, my daughter.

“The Ice-Cream Man”:

“Rum and raisin, vanilla, butter-scotch, walnut, peach:

You would rhyme off the flavours. That was before

They murdered the ice-cream man on the Lisburn Road

And you bought carnations to lay outside his shop.

I named for you all the wild flowers of the Burren

I had seen in one day: thyme, valerian, loosestrife,

Meadowsweet, tway blade, crowfoot, ling, angelica,

Herb robert, marjoram, cow parsley, sundew, vetch,

Mountain avens, wood sage, ragged robin, stitchwort,

Yarrow, lady’s bedstraw, bindweed, bog pimpernel.”

And that list is supposed to go on forever, really. If you like, that’s a kind of a prayer. That’s an agnostic’s prayer. Now, I just — if I can find it — I got this wonderful letter when this poem appeared.

Tippett: Is that from the mother?

Longley: Yes.

Tippett: Yes. I read that she wrote to you, the mother of the ice-cream man.

Longley: Yes. It says, “Dear Mr. Longley, My daughter bought your book Gorse Fires for me after hearing you on the radio. Your verse on the ice-cream man was clear to us, who you were writing about. But I do appreciate very much that someone outside our family circle remembered my son John. The fact that there were 21 flavors of ice cream in the shop, and you wrote 21 flowers, was coincidental. I do bless you for your kind thoughts, and may God bless you. Sincerely, the ice-cream man’s mother, Rosetta Larmour.”

Well, I’m very proud of that letter.

Tippett: What does that mean to you, that letter?

Longley: Everything, really. It means, like, all the good reviews I’ve ever had in my life, rolled into one letter by a woman who probably wasn’t a great poetry reader.

Tippett: And there’s something — I mean, you used the word “transcendence” a little while ago, and there’s — I mean, the flowers that grow so freely are so ordinary, but so beautiful and so — and even the language, right? Their names are so lyrical. It’s almost like each of their names is a poem.

Longley: Yeah. Well, that is all a transcendental experience for me. My heart stops when I discover an orchid. I nearly crashed the car I was driving with my wife to Mayo a few weeks ago, and there was a huge orchid. [laughs] You’re supposed to keep your eye on the road. Well, I’m a danger, as a motorized botanist.

[laughter]

And then, when I hear a bird sing, it goes through me like an electric shock. And these are the things that matter to me. And I would call that transcendental.

[music: “Waltz Sketch” by Paddy Mulcahy]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Michael Longley.

[music: “Waltz Sketch” by Paddy Mulcahy]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today I’m with one of the greatest living poets of Northern Ireland, Michael Longley. His poetry invokes beauty and normalcy, reasserting the vitality of ordinary things, precisely in the face of what is hard and broken in life and society. Together with his late friend Seamus Heaney, he was known as a poet of the Troubles — the word that recalls the 30-year civil war that left 3,600 people dead and as many as 50,000 thousand injured. It ended with the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. I interviewed Michael Longley in 2016, and the long, redemptive work of healing continues to this day.

I listened to something you did for Radio 3 a few years ago, where they asked poets to write their own version of Rilke’s Letters To A Young Poet.

Longley: Oh, yes.

Tippett: You remember that?

Longley: I do, yes.

Tippett: It was lovely. I think you addressed yours — I think it was “Dear Alisún.”

Longley: Alisún, yes. I wanted a nice middle-class Northern Irish name.

[laughter]

Tippett: [laughs] OK. See, I didn’t get that nuance.

So Rilke, in this line which you quoted to Alisún, which I quote all the time, Rilke wrote about love that love is “the utmost, the ultimate trial and test, the work for which all other work is just preparation.” And you’ve said that love poetry is at the heart of the enterprise. But when you say that, you’re taking love out of the little box of romance — I mean, that’s in there, I think, but you say you’re — love poetry about all of the loves of our lives, love in all its forms.

Longley: That’s right, yeah. I mean, I do believe that if poetry was a wheel, the hub of the wheel is love poetry, but then branching out like spokes are the other affections and obligations and responsibilities and loves, like friendship, and loving your country, loving nature, and so on.

Tippett: Right. I mean, I think even in a couple of the poems you’ve read, “The Ice-Cream Man” or “All Those People,” there’s a love of that particular humanity and of this ordinary beauty that’s growing around us all the time.

Longley: Yes. There’s a line by John Clare that I adore — I love John Clare; I revere him — “Poets love nature, and themselves are love.” And I believe that with all my heart, really. And part of writing is adoration. For me, celebrating the wildflowers or the birds is like a kind of worship.

Tippett: And I’m so intrigued to put that together with this kind of poetry, speaking to the Troubles. But that is also this gentle insistence in your work. I don’t think it’s an agenda, right? It’s an effect, right?

Longley: No — no agenda. I stagger around. I’m like a bluebottle bumping into walls. And I had a decade when I wrote hardly anything, in my 40s, and I thought I was finished. And lo and behold, I started to write again. I mean, I have said that where poems come from, I have no idea. And if I have a plan, if I think, “I’d love to write a poem about that,” and I do a bit of homework on the subject, it doesn’t work at all. I’ve got to be taken by surprise. And if I am not surprised, nobody else is going to be surprised.

I had a — this professorship. I was the Ireland Professor of Poetry, which sounds wonderful, doesn’t it?

Tippett: I think it’s the equivalent of the poet laureate.

Longley: Like that, yes. But I wanted to be promoted to the World Poet.

[laughter]

And the thing about it was meeting the young people. I really loved that, and having students. And they used to ask me about my schedule. What do you call it, schedule or schedule? Schedule.

Tippett: [laughs] Schedule, yes.

Longley: And I used to say, “Well, I don’t write anything for ten years, true. And then, all of a sudden, I write three poems in a day, also true.” So that’s it, you see. I mean, I can’t — I don’t really know where it comes from. And wasn’t it Jesus who said, “If your left hand knows what your right hand does …”

Tippett: I think something like that.

Longley: It might be the other way around, right and left. Sorry, Jesus.

[laughter]

“… cut it off.” And I think that’s very good.

And I think one can be too self-conscious. I think art and poetry require a certain insouciance. Otherwise, you’d get knotted, and I think it’s very important — you can take your poems seriously, but you mustn’t take yourself seriously. I’m certain of that, and that self-importance engraves its own headstone. No names, no pack drill. I never can think of …

Tippett: I think you had that in your “Letter to a Young Poet” as well …

Longley: Yeah, that’s right.

Tippett: … that advice.

Longley: I also — did I quote my dear friend, old friend; was a wonderful, grumpy man, John Hewitt? I loved him dearly. But he said [laughs] this wonderful thing to me, once. Somebody was complaining, within earshot, of being under-recognized. And John turned to me, and he says, “If you write poetry, it’s your own fault.”

[laughter]

Isn’t that great? And I believe that too.

Tippett: Well, I know what you did. You said — Rilke said, “Only write poetry if you must,” right? If you can’t not — only write if you can’t not write poetry. And you said that that is a more winsome and practical …

Longley: Yeah, that’s right. I know nothing more exciting than writing a poem. And all of that ten years, I have hoped that I would write another poem. And I did try, but they were all fakes. If you have quite a lot of technique — which now, after 60 years scribbling, I have — it’s too easy to produce forgeries. And there are books upon books full of forgeries. I do believe that if you don’t have anything to say, say nothing, and that silence is part of the enterprise, and silence is sacred too. So I’ve been writing, scribbling away. I wrote a poem today.

Tippett: Did you?

Longley: Yeah. I was going to sit down and have a think about myself, for you. I thought, you know, I was going to try and put on a good show for Krista.

[laughter]

But instead of that, you’ll be glad to hear, I wrote a poem.

Tippett: Did you bring it with you?

Longley: Yes.

Tippett: Would you read it to us?

Longley: Yes, if it can find it in this — I may not be able to find it. I probably can’t find it. OK. What a — imagine what a buildup that was, and I can’t find the bloody poem.

[laughter]

[laughs] Yeah. It was from Homer. It was from The Odyssey. But we can put it on hold, can’t we?

Tippett: All right. Yes, we can. So your — I’ll refer to this one more time, your “Letter to a Young Poet.” You said your two favorite definitions of “poet” are the Scots word “machair,” or maker, and Horace’s phrase, “priest of the muses.” And you said that you’re talking about this: this magic, this mystery that made poets shamans in other cultures …

Longley: Yes, that’s right.

Tippett: … that you’re aware of that.

Longley: I agree with that, yes.

Tippett: And you’ve also spoken of the mystery of form: you prefer the word “shape.” Just talk a little bit about that. It’s so interesting.

Longley: I remember a great professor of Greek, at Trinity, where I read classics — Stanford, W.B. Stanford; very formidable man. And we were doing Aristotle’s Poetics, and he said, “Ladies and gentlemen, I want you next week to bring your own definition of poetry.” And mine was, “If prose is a river, poetry is a fountain.” In other words, poetry uses language in a way that’s free-flowing and, at the same time, shapely. And I do like the word “shape.” I mean, there are much looser utterances that I admire, like Walt Whitman, who seems to me a truly great poet. But I would love to be able to write like that, but I can’t.

It is extraordinary — you start to write, and the first group of lines is a quatrain. And you haven’t planned that. And then the next group of lines is a quatrain. And, say, “Ceasefire,” that began because the episode begins with Priam hugging the knees in supplication of Achilles. I put that at the end, which was a rhyming couplet: “‘I get down on my knees and do what must be done / And kiss Achilles’ hand, the killer of my son.’” And I remember thinking, If I can extract from this episode four quatrains, I have a sonnet. I solved the whole problem. I worked out what I felt, by trying to write a sonnet.

Tippett: Right. So the shape even formed the substance.

Longley: Yes. In poetry, the music and the meaning are inseparable. That’s the mysterious thing.

There’s a beautiful thing — there’s a poet I had loved meeting in New York, called Stanley Kunitz. And he was 100 when I went to see him — beautiful old man. And he wrote, in the preface to his Collected Poems, which I’d recommend to anyone, that form was a way of conserving energy. Isn’t that wonderful? He said the energy soon leaks out of an ill-made work of art. He’s absolutely right. So that’s what form does.

Tippett: I’m going to do my radio thing. I’m Krista Tippett, and this On Being, today in a special public conversation at the MAC Theater in Belfast, with the poet Michael Longley.

I want to ask you also about the mystery of place. And so, Carrigskeewaun is a cottage in County Mayo that you and your wife and family have gone back to, I believe, over many years. And you said something wonderful about the beauty of going back to the same place over and over again: that you notice more and more. It’s not that you exhaust a place — that you go more deeply into it.

Longley: Yes, it’s inexhaustible. Mind you, it is very beautiful, and it’s very remote, and we’ve been going there since 1970. And we carried our children through the river and through the channel, and now they come back over — it’s such a compliment to my wife and me that the children want to spend time with us, and they come back. And they now bring their children, our grandchildren, on their shoulders through this really quite tough terrain. And every time I leave, I think, “Well, there can be no more Carrigskeewaun poems. I’ve exhausted it.” But there always are poems, and the place is inexhaustible.

I mean, you know the phrase, “travel broadens the mind.” We do quite a bit of traveling, but I think it also shallows the mind. But going back to the same place in a devoted way and in a curious way is a huge part of my life, and I’ll be going there even when they have to push me in a wheelchair.

Tippett: [laughs] Through that rough terrain.

Longley: Yeah, and I’ll be like Stanley Kunitz, who celebrated his 100th birthday by publishing a book.

Tippett: [laughs] One poem that I pulled out was “Remembering Carrigskeewaun.” Do you have that one? Or I can — I think it’s in here.

Longley: That’s about as —

Tippett: OK, we’ll see who gets to it first.

Longley: Yes. “See, I don’t know my way around this book,” he said.

That’s not true at all, by the way.

[laughter]

Tippett: Here it is. Here it is.

Longley: Yeah, this was a very special day, when the children were young, and I’m remembering that day in Belfast, thinking of the details. And this is a hymn, if you like.

“Remembering Carrigskeewaun”:

“A wintry night, the hearth inhales

And the chimney becomes a windpipe

Fluffy with soot and thistledown,

A voice-box recalling animals:

The leveret come of age, snipe

At an angle, then the porpoises’

Demonstration of meaningless smiles.

Home is a hollow between the waves,

A clump of nettles, feathery winds,

And memory no longer than a day

When the animals come back to me

From the townland of Carrigskeewaun,

From a page lit by the Milky Way.”

You like that one?

Tippett: [laughs] I do. You said — in another interview, you said, “I don’t go to Carrigskeewaun for escapist reasons. I want the beauty, the psychedelic wildflowers, the call of the wild birds. I want all of that shimmering beauty to illuminate the northern darkness. We have peace of a kind, but no cultural resolution — the tensions which produced the Troubles are still there. It is important for me to see beautiful Carrigskeewaun as part of the same island as Belfast.”

Longley: Yeah. Well, I can’t improve on that, Krista. [laughs]

[laughter]

Tippett: I just — I want to keep shining a light on this gentle way that your poetry speaks, indirectly but very directly, with beauty and with normalcy, with ordinary things — with the liveliness of ordinary things — to also what is hardest and most broken.

Longley: Yes. I’ve very complicated feelings about this. I don’t altogether like the idea that art can be a solace. I heartily dislike the idea that this civic commotion here might be good for art. You know? I really dislike that. That’s on the same level as a big room in the museum devoted to the Troubles. I don’t like that.

Tippett: Right. So what is it? So what is that? What does poetry do? What does it work, if it’s not solace?

Longley: Well, it’s much more complicated than solace. I like the Aristotelian notion of catharsis. And I think what art can do is to tune you up. I mean, if you think of an out-of-tune violin, and tuning it up so that it’s in tune, I think that’s what art is, and that’s what art does. And good art, good poems, is making people more human, making them more intelligent, making them more sensitive and emotionally pure than they might otherwise be. Does that make sense to you?

Tippett: Yes — yes.

Longley: Yeah. And one of the marvelous things about poetry is that it’s useless. It’s useless. “What use is poetry?” people occasionally ask, in the butcher shop, say. They come up to me and they say, “What use is poetry?” And the answer is, “No use.” But it doesn’t mean to say that it’s without value. It’s without use, but it has value. It is valuable. And the first people that dictators try to get rid of are the poets and the artists, the novelists and the playwrights. They burn their books. They’re terrified of what poetry can do.

Tippett: It keeps imagination alive.

Longley: It means that poetry encourages you to think for yourself and to disregard church and state. It does.

But that’s not exactly use. That just means it’s got value. And the image that I love the most — I’ve loved it for years and years — is the English critic Cyril Connolly. And he compared the arts to a little gland in the body, like the pituitary gland, which is at the base of the spine. And it seems very small and unimportant, but when it’s removed, the body dies. In the ashes outside the crematoria in Auschwitz, they discovered scraps of poems. And these were people who were going to their deaths, and they found time to write a poem.

Well, I mean, that says it all, doesn’t it? It just — it’s a normal — it’s a human act of — a normal human activity. I like that idea. It’s a normal human activity. And even in extremis, we’ll turn to it. And even if we’re not writing poems ourselves, we will say poems to ourselves.

Tippett: Even sometimes not realizing they’re poems.

Longley: Yes, perhaps; perhaps, yes.

Tippett: When you were speaking a minute ago about form — the shape that words take and how important that is, and how it also shapes what is said, the effect of what is said — it also strikes me that that’s — and again, I don’t want to be too linear, but it’s modeling something, like a care with words as a core value, as something at the essence of poetry. Poetry would not exist without that care with words. That becomes such a critical work for our society, right? Civic work.

Longley: One of the duties of the writer, the poet, is to use words with precision. I think what poetry does is it uses words at their most precise and their most suggestive. And one word out of place, and the poem’s dead. It’s shocking, but that’s true. And the poets — our poets are custodians of the language. I mean, that sounds very grandiose, but I do believe it.

It’s time to quote somebody else. Let me quote — you know the end of “Mossbawn:Sunlight,” by Heaney?

“And here is love

like a tinsmith’s scoop

sunk past its gleam

in the meal-bin.”

How simple and pure, you know? I love that.

And then I’ll give you some American poetry — Wallace Stevens:

“Oh! Blessed rage for order, pale Ramon,

The maker’s rage to order words of the sea,

Words of the fragrant portals, dimly-starred,

And of ourselves and of our origins,

In ghostlier demarcations, keener sounds.”

Now, I haven’t a clue what that’s about.

[laughter]

Tippett: [laughs] I’m so glad.

Longley: It’s about everything, isn’t it? It’s just — and I’ve had those lines by heart since I was about 20. And when you hear him read them — he was a great reader. And he’s the only poet I know of who was the vice president of a major insurance company. Not many of them around.

[laughter]

Tippett: I’m going to — someone wrote this about you. And I believe you met him at Corrymeela — Richard Rankin Russell.

Longley: Oh, yes.

Tippett: “Longley’s poetry, like Auden’s before him, is religious in the best sense of the word, deriving from its Latin root, ‘religare,’ meaning ‘to bind fast or connect.’”

Longley: Yes, I think that’s right.

Tippett: Will you take that?

Longley: I’ll accept that as a compliment, yes. Yeah, but I wouldn’t dwell on it.

[laughter]

That’s the thing my wife always says about compliments, she says, “Yeah, you accept them, but you don’t inhale.” [laughs]

[laughter]

Tippett: Well, I’d like to maybe — I would ask you one question, which is a vast question. So just how would you start to reflect on this? Through this life you’ve lived and the poetry that has been this magical part of what you’ve brought into the world, how do you think about what it means to be human? What have you learned about that?

Longley: Well, poets are no less or no more human than anyone else. For me, it’s quite an extraordinary gift to see something beautiful — say, like a lark or a flower — and to write about it. For me, no experience is complete, really, until I’ve written about it. And that’s extraordinary. And it’s a way of having more than one life.

And I mean, I have actually been in quite intelligent conversation with people, and they don’t realize that at the back of my head, I’m finishing a poem. So I have this secret life that nobody knows about, except my wife, who is the closest witness to what it’s all about, and the best judge I know.

Tippett: Michael Longley, thank you so much.

[music: “The Sky Is a Blue Bowl (Live)” by Spiro]

Michael Longley has written more than 20 books of poetry including Gorse Fires, The Stairwell, and his most recent collection, The Candlelight Master.

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt, Gautam Srikishan, and Lillie Benowitz.

[music: “The Sky Is a Blue Bowl (Live)” by Spiro]

Special thanks this week to Pádraig Ó Tuama, Edna Longley, Claire Hall, Simon Bird, and the rest of the team at the MAC Belfast for making this live event possible. Also, thanks to Amanda Keith and all the good people at Wake Forest University Press for giving us permission to use Michael Longley’s poetry.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality; supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

The Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

And the Ford Foundation, working to strengthen democratic values, reduce poverty and injustice, promote international cooperation, and advance human achievement worldwide.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.