Image by Brett Simison, © All Rights Reserved.

Three Callings for Your Life and for Our Time

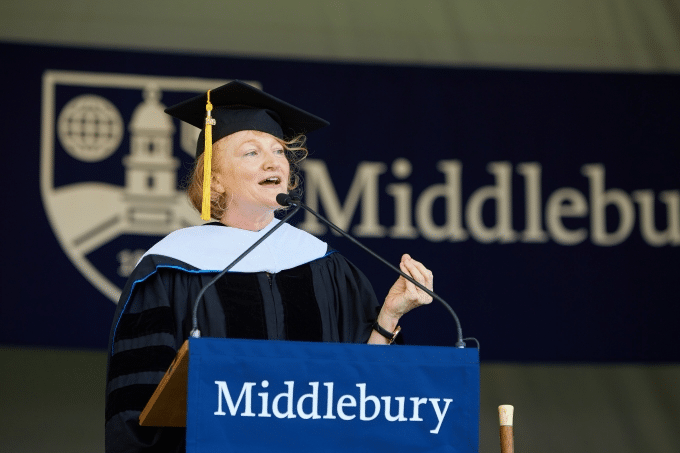

Editor’s note: This speech was delivered on May 26 at the Middlebury College commencement ceremony.

What an honor and a joy to be with all of you.

Thank you for inviting me President Patton and greetings, esteemed graduates and faculty and family and friends — on this day of celebration and transition and passage.

It won’t be lost on any of you that the world too is in a moment of transition and passage. I know that you have received an abundance of messaging in your lives already about all that is broken and seems left to you to fix. What I hope to impart you to this morning is a sense of the abundance you have to work with, too — the grandeur of the calling of being alive at this moment in time and the fact that you and your generation are brilliantly up to this.

It is a strange, redemptive truth of our species that we are made by what would break us. And this is a civilizational moment to get curious and serious about that — to put our wildest creativity and our most vivid, vigorous words to the human capacity to grow and evolve. The great frontier of this century, I believe, is to reckon finally with the hazard and the bounty of what it means to be human. Every dramatic rift of this early century runs through fault lines of human hearts and well-being. Politics has become the thinnest of veneers over human dramas of pain and fear and anger, of dreams and yearning and hope. Our ecological future depends ultimately on human behavior. Our racial future rests as much on the formation of better lives as on the creation of better laws.

The internet is not inventing these problems. It is implicated in all of them, because it is a new canvas for the old human condition, with a power to magnify every dream and every hurt and put them up for the whole world to see. It’s given a new kind of public face to our magnanimity and to the primal, trollish margins of our psyches — which were there all along. It draws us inward and outward, often in the same experience, and so is bringing us back full circle to the challenge of human being and becoming.

I love a line of a poem titled “Vocation” by the late William Stafford. He wrote:

“Your job is to figure out what the world is trying to be.”

I’d extend that a little bit: Your job is to figure out what the what the world is trying to be, whether it knows it or not. You could make a compelling case that the world is doing its best to turn inwards and hurtle backwards. But this poetry breaks my heart open. That’s one of the things a heart is for.

And this is one of the things poetry is for. In society after society, across human history, poetry rises up in times of crisis, when official language is failing us and we must reach anew to give voice to what is deepest and truest about ourselves and the world. Poetry is rising in our country and our world now, driven in part by your generation. So, by the way, congratulations on graduating from a college with a poet at its helm.

That language of vocation is important to me. I commend it to you and take it as one pointer to the way forward. It comes from the Latin “vocare” — calling. Your vocation, in the mid-20th-century world I was born into, was your job title. This was such a diminishment of us. We are called not merely to be professionals but to be friends, neighbors, colleagues, family, citizens, lovers of the world. We are called to creativity and caring and play for which we will never be paid — and which will make life worth living.

And each of us imprints the people and the world around us, breath to breath and hour to hour, as much in who we are and how we are present as in whatever we do. I hear this longing and commitment rising up in your generation: to take up the question of who you will be and how you will be in the world with as much seriousness and joy as the question we’ve privileged in this culture — of what you will do. I see you insisting on joining inner life with outer presence in the world. The pursuit of what it means to be human, in your generation, has become intimate and civilizational all at once.

Given that, I’d like to propose three callings for your life and for our time this morning. The first is moral imagination.

Imagination is our gift as a species to move purposefully towards what does not yet exist and walk willingly through the unknown to get there. It has a power to change what seems possible and so to shift what becomes possible. Moral imagination looks inward as much as it acts outward. It works with a long sense of time and opens its eyes to assumptions that come to us by way of politics and economics, identity and geography, and subtly erode our humanity. It carries its questions as vividly as its answers. It stays curious, even about its own convictions. For it knows that none of us is an equation that computes. Our own positions are never as logical to us as they feel. And so we need to cultivate every form of human intelligence — emotional and spiritual and social as well as economic and political and factual — if what we really want is to approach undergirding truths about the nature of reality, the complexity of human action and inaction, and the possibilities for transformation with which moral imagination would grapple and live.

The phrase “undergirding truths” I borrow from another poet, Elizabeth Alexander. How to muster a shared vocabulary of undergirding truths, of an underlying humanity, is an urgent question in the middle of our life together. How to orient together towards what matters and measure what matters in human terms needs the same magnitude of disruptive, imaginative energy and investment that powers our other forms of enterprise and our wondrous data-generating technologies.

The Northern Irish poet Pádraig Ó Tuama writes:

“When I was a child

I learnt to count to five:

One, two, three, four, five.

But these days, I’ve been counting lives, so I countOne life

One life

One life

One life …”

The second calling for our time that I’d name is wholeness. A genius of the Enlightenment that formed the modern West was a new ingenuity of categories and parts. Our ability to see and study intricacy grew hand in hand with a sophistication, with mechanics and a value of specialization. We divided our sense of ourselves into separate compartments called body, mind, and spirit. We perfected systems for defining an “us” and containing the “other.” We made of the natural world an “other.”

Now, we’re understanding that we live in stardust-infused bodies — and that we’ve inhabited ecosystems while we organized around parts. For us, all of life is revealed in its insistence on wholeness: the organic interplay between our bodies, the natural world, the lives we make, the world we create. And for all our awakening to the power of digital technologies to divide and isolate us, this too is true: Our technologies have given us the tools for the first time in the history of our species to begin to think and act as a species.

Take this in: You are the first generation in the history of your species to come into adulthood possessing the tools to think and act as a species. We’ve scarcely named this wondrous fact in our midst; it stands in such contrast to depths of confusion and fracture all around. But we are, again, creatures who are made by what would break us — and the digital canvas is amplifying that too.

There is paradox here — a sure sign that we’re circling around undergirding truths and the complexity of reality that they hold. Life online is leading to a renaissance of convenings. Virtual connection, it turns out, makes us hungry get together again in the old-fashioned flesh and blood. Even as we spend more of our time in digital realms, our particular identities and the ground beneath our feet are growing more meaningful, not less so. We are taking in the history of the places we inhabit with a new — if profoundly belated — openness and reckoning.

I’m so grateful to be up here today alongside Chief Don Stevens of the Abenaki tribes in Vermont. The On Being Project is located on Dakota land.

And as our technologies take us onto the frontier of our own brains for the first time, we are grasping how they’ve been trying to take care of us, to help us navigate the overwhelmingness of reality, by dividing the world up into categories and binaries — who is in, and who is out; who is human, and who is not; what is what. But now your generation has come along and is reimagining and redefining gender.

I am fascinated to ponder how this move might change us at a species level as it settles.

Gender is at once the either/or by which every human being across time has been defined since birth — and an ultimate proof that to look at any human category closely enough is to see infinite variation. As hard as we try to see where one begins and the other ends, we are shown how interwoven and uncontainable such distinctions remain. The deepest truth held within this, our most elemental category and binary, is the inescapability of interdependence — the sometimes joyful, sometimes maddening, always fact that we need each other.

“There is no them,” the poet, journalist, and novelist Luis Alberto Urrea says. “There is only us.”

Which leads to the third calling I’d commend to you. That is to figure out how love might work in the world you are making — in the world that wants to be: love as a pragmatic, muscular public good.

Love is a word used sparingly in our public places. It is invoked in politics, when it is invoked, as a balm to crisis, not an avenue beyond it. But we are the generation of humans learning to shine a light on hate, to call it out, to take it seriously in legal and political terms. In my mind, this becomes an opening and imperative to summon the same seriousness about love in our life together.

Love is the most reliable muscle of human transformation, the most reliable muscle of human wholeness. And while is it also the most watered down word in the English language, our real-world, on-the-ground experience of love contradicts every objection that love is too “soft” to inform or reshape the disagreements and disarray of our life together in this early century. The challenge is in owning the body of natural intelligence we have about how love actually usually unromantically works in life and offering that up in word and deed.

In the many loves in our intimate and extended circles of friends and family and colleagues and neighbors, love is more muscle than pathos. Our lives of love are full of things that feel impossible and unreasonable in public life right now: hospitable attention, curiosity, generous listening, and meaningful civility — and we exercise them not as ends in themselves but as pragmatic means towards living more abundantly, and towards balancing what we have to say and making sure it can be heard. In real life as we live it, love is only rarely about feeling perfectly understood or perfectly understanding. It may in any given moment have little to do with agreement or likeness. It is shot through with wildness and contradiction just like us, and it could teach us to live together with our wildness and contradictions honored.

I hear the word love rising in our time, feel it as a longing everywhere I turn in politics, in the arts, in ecology, in society — not in the shrill places that get all the attention but in every margin where new, generative realities are being crafted. Everywhere I go I see beautiful lives, breathtaking social creativity, and moral courage unfolding in local spaces where people are incubating the new realities we want to inhabit — clearing some ground to stand on together and begin to speak and learn and move forward together across our fractures with our vitalizing differences intact.

This is always the way change has happened across human history. It never starts in the headlines. It always ferments in the margins between people — one life to one life to one life to one life at a time. And our technologies give us a potential — if and as we choose to shape them to human purpose — to scale the force of relationship: connection, with quality. I wish for you that you take this up as a joy and a privilege of your generation, alongside the better-publicized perils. For you, the work you do inside yourself and to create relationship online and off is of civilizational importance. The life-giving, lifelong work of being ever more deeply human is work you do in service to our beautiful, hurting world.

Pursue moral imagination.

Practice muscular, adventurous, public love.

Plant yourself in a spacious understanding of all the things that add up to your vocation, your vocations, as a whole and multitudinous human being.

Know that you have it in you, wherever you are, whatever you do, to begin to have the conversations you want to be hearing and create the world you want to inhabit. I can’t wait to see what else you have to teach us.

Blessings and congratulations.