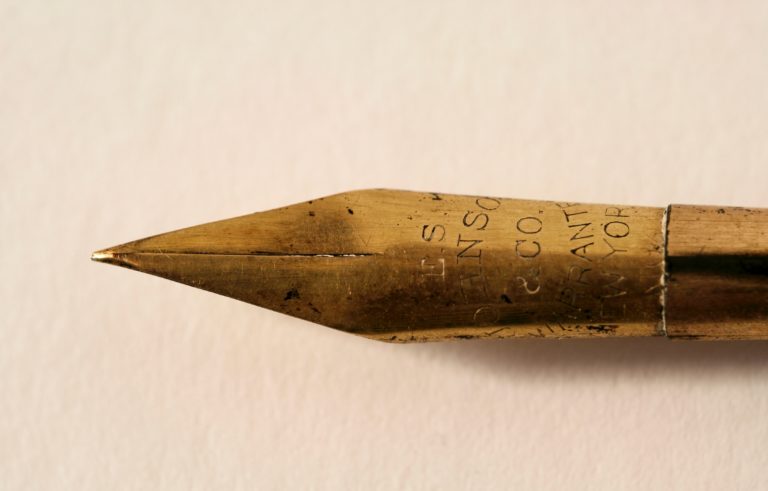

Image by MJ S/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Notes on a Friendship: Abraham Joshua Heschel and Reinhold Niebuhr

Before embarking on my assignment, I would like to ask you to realize how difficult it is to describe a friendship. How can I, how can anyone, describe a relationship between two people without being both subjective and somewhat impressionistic? For, after all, I have no body of literary evidence. There is not a corpus of letters between Abraham Joshua Heschel and my husband, Reinhold Niebuhr, so there is no “hard data,” in the lingo of today.

There is no body of letters. My husband was not a letter writer, nor was he a letter keeper. As he was largely his own secretary, and answered his own letters, unless they were on official Seminary business, he would, as he was no conscientious keeper of letters, just throw them away! I do not know if there were letters thus lost. If a letter came from a friend whom we shared, then he would bring it home for me to see. Then I would keep it.

So, I was lucky enough to keep and to cherish two letters from Abraham to Reinhold. One was a brief note from Rome, undated, but I think we are able to date it. It ended thus: “We are meeting with friends in the Vatican. And scheduled to see the Pope tomorrow. Thinking of you with affection and hope you are feeling better.” Then both of us got letters from him, when he was in Florida, in March 1970, convalescing after a heart attack and a bout of hepatitis. He addressed Reinhold as “Beloved and revered friend.” (I was merely “Dear Ursula.”) But I did get a letter all to myself! He thought that the climate of Florida which had so benefited him might be good for Reinhold, and that was the reason he had written to me too. In his letter to Reinhold he wrote that he was feeling so much better, which made him feel he could write a “pleasant letter, informing you (Reinhold) of my own recovery as an example, precedent and in anticipation of hearing of your recovery.”

He continued, “Such good news from you is what I pray for daily. You are so deeply ingrained in my thoughts, and I am eager to renew our walking and talking together on Riverside Drive.” He went on, “Miami Beach may be intellectually America’s Siberia, still the climate has proved beneficial.” And he continued pressing Reinhold to think of coming to Florida.

So much for the written record. There are brief notes inscribed on articles which he gave us, but there are no more letters.

So what is my material? Memory, which proverbially is a fickle jade. Yet because Abraham was so special, so memorable, I dare to share these memories with you.

I do not know when Reinhold first met Abraham. I think I had that pleasure before he did. One of my Barnard College students was married to a rabbinical student at the Jewish Theological Seminary. They kindly had me to tea so that I might meet that wonderful teacher of the young man at J.T.S. I was, of course, entranced at the prospect, and by the occasion. I remember also that I kept copies of The Earth Is the Lord’s and of The Sabbath in my office. The jackets of both were pinned up on a big board with other topical items outside my office. Many students and colleagues would note these and come in to chat and look at these books. I note that one of our copies is inscribed rather formally to “Dr. Reinhold Niebuhr,” 1952 (the second printing of The Earth Is the Lord’s) “in friendship and esteem.”

It was in February 1952, however, that my husband suffered the first of many strokes. He was out of action for some months, and I am inclined to think he and Abraham did not get to know each other well until somewhat later.

In the middle or later fifties, Reinhold read a paper to the annual joint meeting of the faculties of the Jewish Theological Seminary and Union Theological Seminary. It was later published in the volume Pious and Secular America 1958. This paper, entitled “The Relations of Jews and Christians in Western Civilization,” analyzed the differences between the two traditions in terms of universalism and particularism; of law and grace; of messianism and so forth. He repeated his long-held conviction that Christians should not evangelize their Jewish brethren. Also, he spoke with hope and gratitude for the State of Israel.

This paper was well received, and it may have accelerated the friendship between him and Abraham. By the time Reinhold retired from Union Seminary in 1960, they had become good friends. For the last 12 to 14 years of his life, Abraham really was my husband’s closest friend.

As I have already mentioned, Reinhold had suffered a succession of strokes, from 1952 on. These, although not affecting his speech or his mind, luckily, had nevertheless weakened his general health. It also had then made him more stationary, and although we had some splendid years away, when he was a Visiting Professor at Harvard and at Princeton — also an earlier year when we were at the Institute for Advanced studies at Princeton — he was no longer criss-crossing the country, or going abroad. Abraham, however, was; and, reporting on his travels and on his meetings with different groups of people in the universities as he spoke around the country, he brought that world back to Reinhold, and he would share with him his reactions as to people and the situation in the world outside.

Thus, in the Civil Rights Movement, and his support of and friendship with Martin Luther King, these also formed the subject matter of much conversation between the two of them. I remember so well his telling us about Selma. He was shocked, deeply, to see white Southern women spitting on and yelling at the Catholic nuns with whom he walked, and often would refer to that experience. When riots in Harlem followed the death of Martin Luther King, he went with other religious leaders to see the Mayor of New York. He spoke to us about this occasion, but others, such as Dr. John Bennett, told us of the profound impression made by Abraham’s simple question: How could one pray while such a situation as in Harlem existed?

A week after the bombing of the Baptist Church in Birmingham on September 15, 1963, when four children were murdered, my husband and James Baldwin took part in a T.V. program in New York. There was a regular Sunday program sponsored by the Protestant Council of New York, and usually the host was a well-known minister of a well-known Madison Avenue Protestant church. On this occasion, he excused himself, as he had been abroad, and did not feel up-to-date on situations and issues. So, luckily, as so many of us thought, his place was taken by Dr. Thomas Kilgore, Jr., Minister of the Friendship Baptist Church, and the New York Director for the Southern Leadership Conference.

I do not know if Abraham listened to the discussion, which to me was appropriate to the tragedy being considered, but I do remember Reinhold and Abraham talking about it later. For this was the world where both of them lived their faith. Reinhold not in good health now had to watch from the sidelines. Abraham, although himself frail, was carrying the ball for him, and for many others as well.

Likewise, with the religious coalition against the war in Vietnam, many were the exchanges I caught echoes of, for most of their conversations were when the two of them were together. Sometimes I might join, either their walking and talking on Riverside Drive, or I would come back home and find Abraham chatting with Reinhold. I am sure Sylvia Heschel again had the same experience as I. Sometimes I wished I had overheard more, but Reinhold would tell me what they had talked about and always with great satisfaction.

In the letter from which I have already quoted, Abraham wrote to Reinhold, “You are deeply ingrained in my thought, and I am eager to renew our walking and talking on Riverside Drive.”

This is how I see the two of them in my memory, as I am sure Sylvia Heschel also does. The Heschels lived at 424 Riverside Drive and we, after Reinhold retired from Union Seminary in 1960, lived at 404, so we were only a couple of blocks apart. These walks, ordered by the doctor for Reinhold’s health, when in the company of Abraham, became times of exchange and refreshment. As Reinhold’s own strength decreased in the latter ’60s, he became rather more obviously lame on his left side, but I would watch them — Reinhold over six feet, leaning a bit like the Tower of Pisa, and Abraham, himself not too strong, and a good deal shorter — would he be able to hold Reinhold up if he tilted? One of our devoted doormen at 404 worried, as I did often, when they started, and if I came in, he would alert me and I would go down Riverside Drive looking for them. Luckily, Reinhold never did tilt or tumble, but I still have a vivid picture of those two dear figures happily talking to each other with their different architectural conformations.

I would like, however, to pick up the phrase Abraham used in that letter. “You are deeply ingrained in my thought.” The two were very congenial in their thought, and in different contents and different fashions one often echoed the thought of the other.

This is strikingly illustrated by their common use of words “mystery” and “meaning.” Long before we had the pleasure of knowing Abraham, Reinhold had written and spoken about the mystery of life and the part that faith, and different systems of faith, played in trying to bring meaning into the mystery of the self, into the mystery of creation and the mystery of transcendence. In his inimitable way, as a poet, Abraham expressed this succinctly and vividly, “Is not the human face a living mixture of mystery and meaning?”

Reinhold had written two essays at different times, both entitled “Mystery and Meaning.” The first he wrote in 1945, which was published the next year in the volume Discerning the Signs of the Times: Sermons for Today and Tomorrow, and the other one was written much later, based on sermons which he had preached at Harvard and at Union Seminary and published in the volume Pious and Secular America, 1958. I noted a few characteristic sentences:

“We live our life in various realms of meaning which do not quite cohere rationally. Our meanings are surrounded by a penumbra of mystery, which is not penetrated by reason.”

Or again,

“Faith resolves the mystery of life by the mystery of God‡All known existence points beyond itself. To realize that it points beyond itself to God is to assert that the mystery of life does not resolve into meaninglessness.”

In this same essay, Reinhold continued,

“The sense of both mystery and meaning is perhaps most succinctly expressed in the 45th chapter of Isaiah where, practically in the same breath, the prophet declares on the one hand, ‘Verily thou are a god that hidest thyself, O God of Israel, the Saviour,’ and on the other, insists that God has made himself known: ‘I have not spoken in secret, in a dark place of the earth: I said not unto the seed of Jacob, Seek ye me in vain: I the Lord speak righteousness, I declare things that are right.’ This double emphasis is a perfect symbolic expression both of the meaning that faith discerns and of the penumbra of mystery it recognizes around the core of meaning.”

Mystery and meaning likewise was central in Abraham’s thought, as all of us knew well.

“It is in the awareness that the mystery we face is incomparably deeper than we know that all creative thinking begins.”

Or again,

“To maintain the right balance of mystery and meaning, of stillness and utterance, of reverence and action seems to be the goal of religious existence.”

Or yet again,

“Sensitivity to the mystery of living is the essence of human dignity. It is the soil in which our consciousness has its roots, and out of which a sense of meaning is derived. Man does not live by explanations alone, but by the sense of wonder and mystery.”

It was no wonder to me that these two friends found each other so congenial, not only in this shared universe of discourse, but also in their dependence upon and reference to the Hebrew prophets. Reinhold always emphasized that it was the prophetic vision of the transcendent righteousness of God that gave both the standard and the dynamic for ethical action. It was the eighth and sixth century prophets who inspired my husband’s thought and work in the field of social ethics. Abraham’s great book on the prophets, when we read it in its English translation, we agreed should be required reading for every minister and teacher.

Before I had read the book, talking about Abraham with my husband, I had said, “Is he not a prophet of Israel?” But then we did not think he was angular enough! Reinhold replied, “Perhaps he is too benign in his character.” Yet, in the introduction to that book, Abraham writes, “Prophecy is a sham unless it is experienced as a word of God swooping down on man and converting him into a prophet.” I think others would agree with me that the word of God had indeed “swooped down” on these two friends. I have forgotten where it is that Heschel wrote, “The prophets look at history from the point of view of justice, judging its course in terms of righteousness and corruption, of compassion and violence.”

A few weeks ago a young church historian sent me a couple of pamphlets issued during the First World War and published by the War Welfare Commission of the Evangelical Synod, the denomination in which my husband was brought up and in which he served. (Afterwards, it became part of the United Church of Christ.) Reinhold had not been accepted as a chaplain owing to a heart murmur, but he was used as a sort of chaplain to chaplains, whom he visited and kept in touch with in the military camps in this country. There was a short column in one of the pamphlets, with the title “Imitating God.”

As I read it, I thought to myself, “I think Abraham would have approved of this.” Reinhold wrote, “Imitate God? Our minds will not compass the universe or comprehend its mysteries as does the mind of God, but we can imitate his ability to look into the souls of men? Then too, we can imitate the holiness of God. We will never achieve it. It sets a goal before us that can never be reached and that therefore always keeps us striving.” Somehow, this reminded me of the words of Abraham: “The goal is that man be transformed; to worship the Holy in order to be holy.”

Observing, and now remembering, the friendship between these two men, I realize that it was the extraordinary openness in exchange with others that made Abraham such a unique person and unique friend. Was this a gift, a particular grace that was given him? So we might think, yet in his utterances it was this quality that to him was part of biblical religion. “The demand as understood in biblical religion is to be alert, and to be open to what is happening.” (This is from the book Who Is Man?)

Abraham was all of one piece; his manner of meeting others, of listening to them, his interest was all part of his belief about life. I am reminded, as no doubt others have been, of the remark of Loren Eisley: “The habit of prayer, by which I mean the habit of listening.” Abraham listened to his friends, to those who needed understanding and support, whether individuals or groups, but he listened to God. This openness was not only to his fellow human beings but to the word of God. The habit of listening, Eisley’s phrase, was for him indeed the habit of prayer. Again and again the relationship of the transcendent to the immediate happenings of historic existence, these were noted no only in his writing but in his actions. There was a transcendent meaning in the necessary actions of daily life, so he reminded us again and again, “Awe enables us to sense in small things the beginnings of infinite significance, to sense the ultimate in the common and the simple.”

But I have said enough. As Abraham might say, “May I tell you a story?” I really want to tell two stories. One day in early spring, when the fallen snow had become a horrid, muddy flood, swooping round the corners of the streets, I was approaching 122nd Street off Broadway. I saw coming from different directions two figures whom I knew. One was a gentleman who was my hairdresser, Mr. Aris. When I had first heard about him, I had thought he was Mr. Harris, but he might have dropped the “H.” He turned out to be, however, a Greek, from the Island of Crete. The other figure was Abraham Joshua Heschel, who was just back from Jerusalem. (I think it was the time when he came back with his beard!) All three of us converged, trying to leap across the particularly dirty, muddy mess which was characteristic of New York in the melting-ness after a snowfall.

I was greeted by both gentlemen, and grasping the leashes of my two poodles firmly, I introduced them to each other, The Rabbi Heschel and Mr. Aris. Suddenly remembering Tertullian‘s rhetorical question, “What has Jerusalem to do with Athens?” I told Abraham that Mr. Aris had just returned from Greece, but had been born in Crete. “Ah,” said Abraham, “the birthplace of Zeus.” This hit a bull’s eye, and Mr. Aris was enchanted, and asked Abraham if he had been to Crete. I was too busy trying to control the poodles and not get completely drowned in the mud to remember what happened, but I do remember the choreography of that meeting where there was a tremendous amount of interest shown by Abraham, very characteristically, in the background of Mr. Aris. “What was he doing? And How did he like living in America,” and all the rest. Both gentlemen told me afterwards that they had so enjoyed the meeting. Although there is nothing very much to this story, somehow it seemed to me so characteristic of Abraham.

The other story connects up with one of the letters I had mentioned earlier. On a lovely Friday afternoon, my husband and I returned to our apartment house after a walk along Riverside Drive. Our very pleasant doorman told us that our friend had dropped in, and on learning we were out had left with him a gift for us. The doorman took this from some safe place and presented us with a bottle, wrapped up in silver foil. We asked whether he knew who had left it. He answered that it was the learned gentleman with whom Professor Niebuhr walks. I triumphantly exclaimed, “Abraham, no doubt.” The doorman continued, “He said he had just come back from Rome, and that he had seen the Pope.” I am afraid I let out a somewhat unladylike cry of glee, and said, “Heavens! This must be holy water!”

We went into the elevator and upstairs. Entering our apartment, and while helping my husband off with his coat, he said to me, “You must ring Abraham up at once and thank him.” I looked out of the window across the Hudson where the sun had dropped behind the horizon of New Jersey. I said, “I don’t think I should, the sun has set and Shabbat has started.” At that moment, the telephone rang. It was Abraham, “I’m back. Have you got my present? It is brandy for Reinhold. And I did see the Pope.” “Abraham,” I squealed, “I was going to ring you up to thank you, Reinhold is right here, but the sun has set; so of course I didn’t.” “It is all right. There are two more minutes to go, and I wanted to be sure. I’ll see you soon. My love to you both.”

This speech was delivered by Ursula M. Niebuhr at the College of St. Benedict on May 16, 1983.

Share your reflection