Image by Phillipe Merle/AFP/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

A Broken Bequeathal of Shame: Diaspora Stories of the Armenian Genocide

“Every time you weep, I feel the surface of a river

somewhere on Earth is breaking.

You wipe your eyes as you read

aloud a letter from the old country.

From the floor, I watch the curls of the words

through the sheer pages.

Your brother and sisters have gathered

around you. I don’t understand

the language but feel a single breath

of grief holding this room.”

—Elmaz Abi-Nader, “Letters from Home”

I am a 38-year-old American of Armenian descent. Until this year, I knew nothing about the Armenian genocide.

I grew up in a suburb of Los Angeles, California as the daughter of immigrants from Tokyo and Tehran. Whenever the phone rang in our house, my parents answered it in English. “Hello?” It was a moment in which the world stopped its orbit, the birds paused their song, and I’d freeze whatever I was doing — playing, eating, reading — to listen.

Everything hung on the next sentence. If my mom continued in Japanese, her voice would ripple over the receiver in joy, tumbling down the curly cord in silver-sounding waterfalls of laughter. If my father continued in Armenian, this usually began with a chortling snort, followed by affirmations that sounded like, “I am well, we are well.”

I would continue to eavesdrop, even after they moved gingerly into another room, out of view but not of earshot. The earth’s orbit, the bird’s song, and my life could recommence because I could hear that my parents were happy.

Speaking in their mother tongues, they shed the layers they wore to survive in America, removed from a cultural vocabulary that was self-evident for them. Laughing into the receivers, they seemed to temporarily revert into rarer, more genuine versions of themselves. How grateful I was for the people on the other end, ever thankful they had called my parents.

Like the Lebanese-American poet Elmaz Abi-Nader, I am the child of expatriates, born into the generation after immigration. Abi-Nader describes a familiar view from the periphery of her parents’ longing for their home countries. The distance for her parent is too great, represented in the letter that is stained by tears at its reading.

But the distance to her parent’s homeland is also a source of pain for the child herself. She cannot understand the language read aloud; she cannot decipher the strange, curly script shining in reverse through the transparent stationery. She is physically and culturally removed from the “old” country and the faceless family who seems to materialize around her weeping parent, whom she cannot help.

Abi-Nader captures the experience of the child who cradles her parent’s expatriation. Conscious of her parent’s otherness, she is grateful for the sacrifices they have made living in a place that is not naturally home to them. She is protective of their displacement, pained by their homesickness, and relieved by every evidence of their happiness.

While Abi-Nader watched her parents read letters from home, I hung on every foreign phone conversation. Next to Armenian, my father also spoke Farsi — like most of his friends and relatives, he was an Armenian from Iran. His father, Vahan, was an Armenian pharmacist from Hamadan, Iran. His mother, Heghineh, was an Armenian poet from Tblisi, Georgia. Her family immigrated to Iran, where she met my grandfather.

After he passed away, she immigrated with her sons to Los Angeles. Many of my father’s cousins, second-cousins, classmates, and neighbors also immigrated to join my father in L.A. or settle elsewhere. I have Armenian family in Paris, Sydney, Moscow, Reno, San Francisco, Glendale, and Yerevan. I have come to understand that this is what is meant by the “Armenian diaspora.”

I followed in my family’s footsteps when, 15 years ago, I became the third consecutive generation to leave home. I moved to the Netherlands, where a Hague conference took place last month to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of the Armenian genocide. There, I learned of a cultural history of which my own family has never spoken.

Genocide is a term that, in European context, has a common and undisputed reference in the Shoah. It is also a term swiftly associated with tragic histories in Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia, and Darfur. The Armenian genocide, which took place in what is present-day Turkey, has less consensus among contemporaries. In diplomatic terms, it has been referred to, for example, as the “Armenian issue.” In 2014, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan offered condolences to the Armenian grandchildren of those killed during what he called the “events” of 1915.

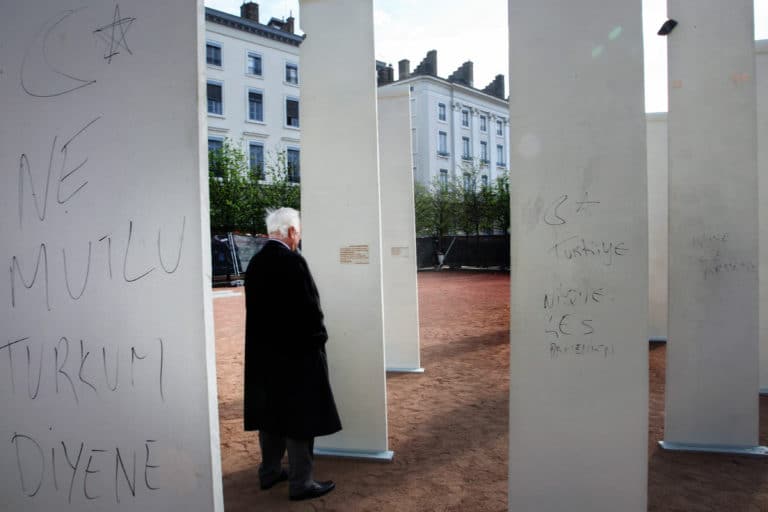

Blunt recognition, however, crops up unexpectedly from unwelcome places. In a recent speech at the Dutch monument for the Armenian genocide, Geert Wilders, a Dutch member of Parliament known for his anti-Islamic politics, framed his appeal for genocide recognition through fearmongering on “the cruelties of Islam.” In their persecution of the Yezidi tribe, who offered shelter to Armenian Christians in the Syrian desert a century ago, even Islamic State militants acknowledge the massacre that took place. One of the earliest documented admissions came from Adolf Hitler himself, who, in motivating his military staff to invade Poland, asked the rhetorical question: “Who, today, remembers the Armenian people?”

Historians, journalists, and academics at the Hague conference in March demonstrated, slide after slide, and established an unquestionable case for genocide. Old photographs, statistics, and the terms outlined in Article II of the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide made clear that the question is not, “Was this genocide?” but rather, “Why the universal silence?” For the span of a century, even now that incriminating information is available at the click or swipe of every fingertip, civilization has hesitated to universally acknowledge the deaths of 1.5 million Armenians in the Ottoman Empire from 1915 to 1923. Why?

Denial, practiced on the part of perpetrators and governments, is one obvious explanation. But the stories told by descendants of Armenian immigrants yield their own two-fold silence: the silence of the dead, and the self-imposed silence of survivors.

In her 2011 documentary film Grandmother’s Tattoos, Suzanne Khardalian, a Lebanese-born Armenian, tells how the taboo around her grandmother’s genocide survival was bequeathed through subsequent generations. Having immigrated from Lebanon to Sweden, Khardalian returns to her birthplace and asks her family about her grandmother’s tattoos:

“Why did Grandma have tattoos on her face and fingers, and what did they mean?”

Incomplete answers lead her to the Syrian desert city of Deir ez-Zor, which served as the final destination for Armenian death marches in 1915. There, native Syrians lead Khardalian across an expanse of sand mixed with the remains of century-old human bones. She bends over, scoops up a handful of earth, and finds a tooth. Through gasps and tears, she cries out in Swedish, apparently directed to the person filming behind the camera. The lens follows her into the Armenian Genocide Memorial Church, which the Islamic State destroyed a few years later.

From Sweden back to Lebanon, to Syria and Los Angeles, Khardalian follows her family trail and pays homage to the oldest living members in her matriarchal lineage. Her mother discloses parts of a story she heard from the sister of Suzanne’s grandmother. In 1915, the sisters and their mother attempted to flee in a boat steered by a Turkish soldier. Twelve-years old at the time, Suzanne Khardalian’s grandmother was sexually assaulted by the soldier. The tattoos were given to her, her sister, and many other young Armenian female survivors who were taken up as slaves or second “wives” in Turkish households until the end of the First World War. Growing up 20 steps below her grandmother’s flat, Khardalian and her four sisters, who had vaguely read about the genocide in their schoolbooks, never suspected a family history. They had inherited only silence, broken by Khardalian’s curiosity as a documentary filmmaker.

Khardalian’s family history excavates a primary motor in the machine of Armenian genocide denial.

“Shame is organized by gender,” Brené Brown explains in her TED talk. “Put shame in a petri dish and it needs three things to grow exponentially: secrecy, silence, and judgement.”

Having lost family members, witnessed horrors, and suffered sexual abuse, those Armenian women and children left behind numbed their pain, and in the act of numbing, repressed their histories. Because denial was a means of continued survival for them, they did not “live to tell anyone about it.”

“We lived with her, and you wish you could have done something. At least comfort her…We’ve never talked and realized this happened to our grandmother,” mourn Khardalian’s sisters. In deep regret of their ignorance, they demonstrate a willingness to have listened to their grandmother’s story, had they been given the chance.

Brené Brown urges that “all we need to do is respond to someone’s shame by really listening.” As a survivor in the family of the poet Peter Balakian put it, these “events of the past were not only too painful, they were beyond words.” Yet Balakian’s book Black Dog of Fate and Khardalian’s film have contributed to a canon that subsists by the grace of survivors who, at some point, felt ready to tell their stories to an empathetic audience.

Listening requires vulnerability — on both the parts of the speaker and the listener. How willing has the rest of the world been to listen to the stories of the Armenian genocide? Have we given Armenians and Turks a safe space to “show up,” as Brown urges, “to really be seen for who they are” — with their scars and traumas, or their transgressions and remorse?

In an unprecedented step, two young Dutchmen have marked the one hundredth anniversary with Bloodbrothers, a controversial documentary series aired at the Movies that Matter international film festival. Ara Halici, a Dutch-born Armenian, and his friend Sinan Can, a Dutch-born Turk, filmed their collective research into their respective family histories surrounding the events in the Ottoman Empire around 1915. While searching for credibility behind the claim that Armenian losses were a mere casualty of war, Sinan Can learns about his Turkish great-grandfather’s culpability through the appropriation of property belonging to deported Armenians. Ara Halici, on the other hand, is confronted with absence of his ancestral Armenian home, his great-grandmother’s forced marriage as a second wife to a Turk, and the extermination of a large number of his father’s side of the family.

Diaspora serves as the “third place” for these friends who, as Dutch-born children of immigrants, share turf, bi-cultural identity, and language. It is the common ground on which these men are able to meet and set the terms for a collective undertaking into uncertain territory. As Brené Brown cites in her On Being interview, vulnerability requires “uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure.” It is about becoming comfortable with the uncomfortable. It is about the courage and readiness to participate in a process that might not turn out in one’s favor.

As representatives from opposite sides of a century-old conflict, Ara Halici and Sinan Can are unique in their willingness to be vulnerable together.

Travelling as companions, they undergo individual experiences that test their loyalty to their friendship. Despite these tests, they remain in conversation: they talk to each other about their feelings. They become architects of a safe haven for their personal struggles and their discomfiting family histories. In crafting this space, they forge a path away from the cultural practice of shame and denial — and in the direction of authenticity. Here, too, resounds the “cold, broken hallelujah.” Ara Halici’s voice speaks over an image of the two men travelling in the same couchette: “De man die naast me ligt zou eigenlijk mijn vijand moeten zijn. Maar ik noem hem mijn broeder.” (“I’m supposed to see this man lying across from me as my enemy. But I call him my brother.”)

At some point after her birth in 1904, my grandmother, the Armenian poet, immigrated from her birthplace in Georgia to Iran. She was 11 years old in 1915. The genocide of her people would not have escaped her consciousness; in the worst case, her migration took place on its periphery.

I may never know how my family experienced the events of a century hence. But as an Armenian, I am bound to this tragedy. I belong to the larger diaspora grieving for the sorrows of our ancestors.

The diaspora has made us all children of immigrants. As Armenians, we are all the poet Abi-Nader, having watched our parents and grandparents read letters from “the old country.” We are all children who have listened to our mothers and fathers answer the telephone in another language. We have cradled their expatriation, successes, and suffering.

Commemorating the events that began in 1915, we watch as bygone family members materialize around our elders. We wait as the willing architects of a safe haven for their stories, and we invite the world to listen with us.