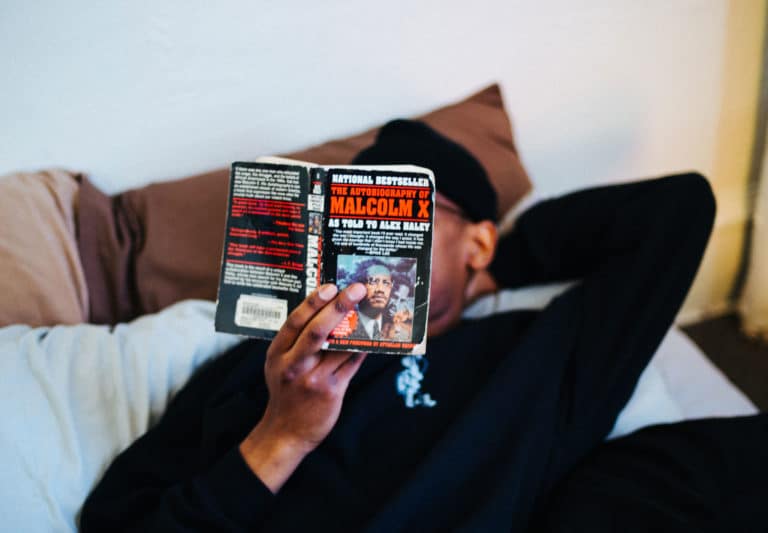

Image by Wale Agboola, © All Rights Reserved.

Radical Justice, Gentle Spirit: Malcolm X’s Message for America 50 Years Later

“Who taught you to hate yourself?”

I was 18 years old when I first read The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Up to that point in my life, I had not encountered people of color here in America who talked like him, thought like him, and stood up like him. I had seen such fierce revolutionary people around the world: brash, defiant voices that condemned colonialism and exploitation, but less so here in America.

Coming from a recent immigrant family, we were taught to fit in, blend in, perform our “American-ness” by chasing the gospel of success. When called upon, we were to talk about America as a land of opportunity and dreams. But here was this beautiful and bold black prince, standing up to white exploitation, asking in a strident tone:

“Who taught you to hate the texture of your hair?

Who taught you to hate the color of skin,

to such extent that you bleach your skin to get like white man?”

This obsession with whiteness, this equation of whiteness and perfection/beauty is of course a lingering issue in America. It is also a recurrent theme globally where “fair and lovely” is idolized and idealized by folks from South Asia to Iran to Arab cultures. Malcolm’s voice was a defiant, prophetic voice of communal love, one that roared again and again to remind us: you cannot be free until you begin to love yourself, love your community, love who God created you to be.

“Who taught you to hate yourself

from the top of your head to the soles of your feet?

Who taught you to hate your own kind?”

Twenty years before Bob Marley, it was Malcolm who told us to emancipate ourselves from mental slavery.

The white racism of American society was not ready (or more properly, not willing) to hear this message in the 1950s and 1960s. The first time that Malcolm was brought to the attention of the wider American society was a 1959 documentary by Mike Wallace called The Hate That Hate Produced:

I wonder how ready and prepared we are to hear this message today. When anyone points out the ways in which we as a community are falling short of our own lofty ideals, the accusation is that somehow you are a “hater,” “a traitor,” and “ungrateful.”

In particular, I wonder why we have such a hard time listening not just to suffering and grief from people of color, but more specifically rage and outrage. Forget the academic lamentation of “Can the Subaltern speak?” Today we wonder: “Can the person of color give voice to rage and outrage in public?” Malcolm told us not to be surprised if those who have been suffering cry out in rage to let you know they’re hurting.

Martin Luther King and Malcolm X both expressed profound disappointment with America, but in slightly different tones. Martin says to us: I love America enough to be disappointed in her.

“There is no great disappointment where there is also not great love.”

Martin says that when our founding documents state that all men (presumably including all women) are created equal, that includes all black men and women. Martin speaks of a world in which the destiny of black people is wrapped up in America’s promise.

Malcolm’s answer has a different resonance. Instead of being addressed to the American society at large, he begins by addressing his own black community, those who have experienced the brutality of America. For Malcolm, America’s language of equality for all is nothing short of hypocrisy until, and unless, we in fact treat all as equal. Until then, as Malcolm says poignantly, “Democracy is hypocrisy.”

This is American “justice”

This is America “democracy.”

Those of you who are familiar with it

know that democracy is hypocrisy. …Democracy is hypocrisy.

If democracy means freedom

why aren’t our people free?If democracy means justice

why don’t we have justice?If democracy means equality

why don’t we have equality?

This language, this frustration is one that echoes again and again among all who have experienced the betrayal of the lofty language of America, like the “black bard of Harlem,” Langston Hughes:

Let America be America again.

Let it be the dream it used to be.

Let it be the pioneer on the plain

Seeking a home where he himself is free.

(America never was America to me.)

….

I am the poor white, fooled and pushed apart,

I am the Negro bearing slavery’s scars.

I am the red man driven from the land,

I am the immigrant clutching the hope I seek–

And finding only the same old stupid plan

Of dog eat dog, of mighty crush the weak.

….

O, yes,

I say it plain,

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath–

America will be! –

We love to honor and celebrate America as a dream that Martin sang about:

“I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal’.”

Malcolm points out the necessary, complementary perspective that all too often, at the beginning and yes even now, America is also a nightmare for far too many:

What is looked upon as an American dream for white people

has long been an American nightmare for black people.

Of course we forget that the same Martin, under Malcolm’s influence, would say four years later that he too had been too quick, too idealistic, about the dream.

Martin and Malcolm were indeed moving closer to each other’s points of view.

Yes, America is both a dream and a nightmare. It has always been, from the very beginning, and continues to be so. Malcolm talks about the experience of America from the perspective of those who have experienced America not as a shiny city on a hill but rather as a corrupt, violent, and racist empire. He rejects this facile and un-experienced “American-ness,” and instead embraces his African roots:

“No, I am not an American. I’m one of the 22 million black people who are the victims of Americanism; one of the 22 million black people who are the victims of democracy, nothing but disguised hypocrisy.

So, I’m not standing here speaking to you as an American, or a patriot, or a flag-saluter, or a flag-waver. No, not I. I am speaking as a victim of this American system, and I see America through the eyes of the victim. I don’t see any American dream; I see an American nightmare.

Truth and history is never linear. America’s story is not just the story of pilgrims landing in America, but as Malcolm says:

Our forefathers weren’t the Pilgrims.

We didn’t land on Plymouth Rock.

Plymouth Rock landed on us.

There is no post-racial America, at least not yet, and nowhere in sight. The demons of racism, classism, Islamophobia, anti-Semitism, xenophobia, sexism, homophobia, and empire are all still with us. And Malcolm was no post-racial figure. As long as racism, exploitation, and oppression persist, he was always going to be a “Black nationalist freedom fighter” (his own words). And yet there was something that he experienced in Islam that pushed him to revise and re-evaluate his own ideas.

“America needs to understand Islam, because this is the one religion that erases from its society the race problem. Throughout my travels in the Muslim world, I have met, talked to, and even eaten with people who in America would have been considered ‘white’ — but the ‘white’ attitude was removed from their minds by the religion of Islam. I have never before seen sincere and true brotherhood practiced by all colors together, irrespective of their color.”

Muslim societies too, like all human societies, wrestle and wrestle with their own demons of racism, color prejudice, sexism, and classism. And yet Malcolm saw something of beauty in his experience of pilgrimage to Mecca. It was that something, that spirit of brotherhood (and sisterhood) that led him to say:

“You may be shocked by these words coming from me. But on this pilgrimage, what I have seen, and experienced, has forced me to re-arrange much of my thought-patterns previously held, and to toss aside some of my previous conclusions.”

Here is the mark of great human beings: the ability to grow, to revise, and re-arrange one’s thought. This willingness to modify, adjust, adopt, pivot, and re-direct is in fact the sign of intellectual and spiritual vitality. The refusal to adjust is a sign that we have made idols of our own beliefs. But let us honor Malcolm and not pretend that his experience in Mecca, his conversion to a globally recognized model of Islam somehow made him a post-racial Malcolm. Upon returning from Mecca, Malcolm was asked if he would use the Muslim Arabic name that he had used overseas in African and Asia: al-Hajj Malik el-Shabbaz. He answered that as long as exploitation and oppression continued in America, he would continue to go by the name that contains in it the haunting memory of the loss of identity, the loss of language, the loss of culture, the loss of religion: X. Malcolm X.

Today marks 50 years to the day since Brother Malcolm’s assassination on February 21, 1965. All we need to do is to listen to Malcolm on police brutality and see the relevance of Malcolm’s roar to Ferguson, to Trayvon, to Eric Garner, and a thousand other victims:

As a no-longer-young man who continues to read Malcolm and Martin side by side and draw inspiration for today’s world, I keep in my heart both the promise of a dream for all and the reality of a nightmare for far too many. As Malcolm said, the response is not to assure my own personal well-being, but rather to transform the structures and institutions that produce suffering for so many.

And there is one last beautiful point: Malcolm embodies a fierce and radical critique. He was radical justice embodied, linked to a fierce love that began with the love of a black community so exploited and oppressed.

Here are the words of Ossie Davis, given at Malcolm’s funeral 50 years ago:

“Did you ever talk to Brother Malcolm? Did you ever touch him or have him smile at you? Did you ever really listen to him? Did he ever do a mean thing? Was he ever himself associated with violence or any public disturbance? For if you did, you would know him. And if you knew him, you would know why we must honor him: Malcolm was our manhood, our living, black manhood!

This was his meaning to his people. And, in honoring him, we honor the

best in ourselves. …And we will know him then for what he was and is — a prince — our own black shining prince! — who didn’t hesitate to die, because he loved us so.

This may be the lesson that all of us are called to take to heart: to be walking in the footsteps of this giant, we have to learn to be simultaneously radical in our stance against oppression and gentle in heart.

Radical gentleness: an idea whose time has come. Rest in power, our own black shining prince, our own Muslim prophetic voice of justice.