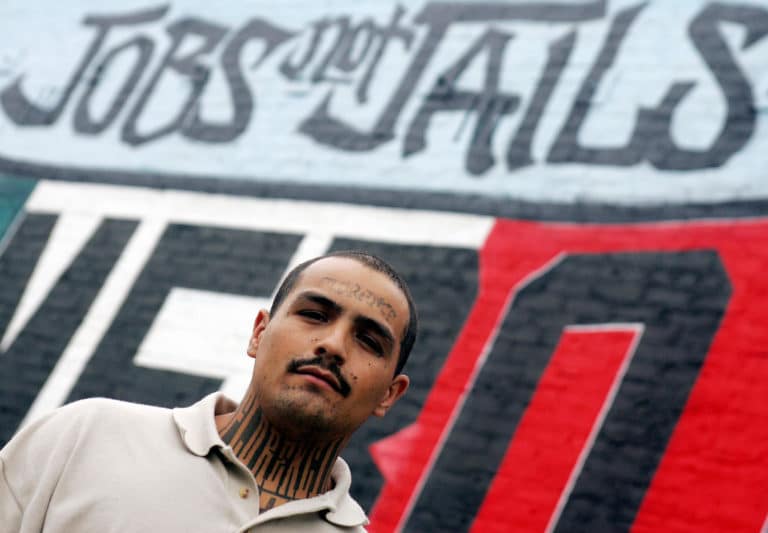

Image by Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Re-Humanizer, at Your Service

Scale.

It’s the buzzword of the social entrepreneurship sector — jargon for, in essence, how big can this thing get? It is philanthropists’ go-to question.

Let’s say you’re building a training model to help farmers in the Global South (the majority of which are women, by the way) increase their crop yield and grow themselves out of poverty. Okay, but how many farmers can you train and how fast?

Or you’re a mover and changer stateside: an organization that tries to demystify the world of science, technology, and math for teenage girls. Is there some technological fix that can bypass the slow, emotional work of empowering girls one-on-one?

Or you’re a doctor trying to transform the way people die in this country. Noble work, but how many people can you fit into your hospice and what is the turnover rate and cost for the beds?

None of these are bad questions. In fact, if you’re not outraged at the glacial pace of change on just about any issue you care deeply about, then you’re not paying enough attention. With the unrelenting pace at which our climate is degenerating and vulnerable people are suffering from unnecessary disease and indignity, we need solutions that can move far, fast. Sometimes, a question about how many people can be reached with a given model is the perfect question.

But, a word of caution against worshipping at the feet of scale.

Not every great solution is a franchise. Sometimes, changing the world is really, truly about changing one person’s experience within one dehumanizing system. Yes, the ultimate goal needs to be changing the system, or at least rehabilitating it with an eye towards reducing harm (here’s looking at you, prison industrial complex.) But, until that system is changed, while that system is changed, we need gritty, gracious people who will show up and look other people in the eye and talk to them like they are deserving of second chances, explanations, (tough) love.

I learned this important lesson from Raul Diaz, a prison re-entry social worker at Homeboy Industries. Re-listening to Father Greg Boyle and Krista in conversation reminded me of Raul’s invaluable lesson. When I was in my late twenties and feeling deeply disillusioned about my capacity to make change (nothing felt “big enough”), I set out across the country to interview activists around my age. How did they get up, day after day, and face the heartbreak, the losses, the absence of glory? How did they measure success? How did they know their work mattered?

Raul answered me in no uncertain terms, not through his words but through his deeds. He was laughter. He was patience. He was fierce, when he had to be. Here’s an excerpt of the profile I wrote of him in Do It Anyway:

“Raul says he wants to take me to lunch for some ‘real Mexican food.’ We sit across from one another in a booth sipping on giant drinks — Coke for him, Horchata for me — and talk about his clients. There’s something about the blaring Spanish music in this Mexican mall, the chaos of all of the vendors selling cheap toys and cowboy boots and knock off bags, that makes it feel safe to speak on such difficult subjects. The chaos surrounds us like insulation.

‘The guys have three minutes to eat sometimes, five minutes to shower. They’re not treated like human beings,’ Raul explains, the anger visible on his face. He, and two other case managers at Homeboys Inc., are currently nearing the end of a two year grant from the Department of Juvenile Justice — the purpose of which is to help young people from the LA County Area between the ages of 18 and 25 re-enter the real world after incarceration. Raul’s case load of 60 is filled with ‘hardcore’ guys — murders and drug offenders; the public defender’s office started referring the most difficult cases his way after realizing how successful he was at cracking their previously impenetrable facades.

Raul’s job description is technically ‘case manager,’ but ‘re-humanizer’ sounds more appropriate. What he does with his clients goes far deeper than preparing their ‘re-entry plans’ — housing, job training, mental health services etc. He meets with them frequently, gets to know them through a series of intuitive questions about the relationships they’ve had — Where’s your dad at? Usually in prison or missing. Where’s your mom at? If no mom — How was foster care? How was your social worker? Raul will talk with them about baseball, the never ending drama with the corrections officers (most of whom don’t like Raul because he tries to circumvent the prison bureaucracies), their families back in Boyle Heights, even their crimes.

Raul is all instincts. He describes an exercise that he made up and uses frequently with clients to get them to reflect on their crimes: ‘I pretend to be the victim: I kissed my daughter this morning. Hugged by wife before I left the house. Headed out to get a loaf of bread and some milk, and your punk ass came to the bus stop and robbed me at 4am. Do you know what it was like to have a gun in my face? When you robbed me, you robbed my pride, you took away my balls.’

At this point, some of his clients will still act hard about it, at which point Raul breaks out the mom card: ‘How would you feel if it was your mom standing at that bus stop at 4 am and some hardcore guy came and put a gun in her face? You rob people of their freedom when you do this shit, dog. You make them feel like they can’t be safe in their own community. So you tell me, should you get parole yet?’

Many of them will simply say no, their eyes softened by the mention of their mothers, the ‘gangster mentality,’ as Raul refers to it, cracked. Some say yes: The ultimate punishment is to parole me. I got nobody.

‘That’s where the relationship really starts,’ Raul reports. ‘That’s when I really gain their trust because they know that I see the truth about what they’ve done and I’m still going to care about them.’

Raul knew his work mattered, not because it scaled, but because it transformed one life, then another. He would lose one, then save one. Lose another, save another one. Sort of. Over time. Depending on your definition. He knew his work mattered because he kept looking these guys in the eyes and telling them that they deserved good lives, that they were capable of goodness, that he cared about them, unconditionally.

That tiny, overused word — scale — doesn’t fit around work like that. You can always hire more social workers, so in that sense “scaling up” is possible, but you can’t mess with the amount of time and energy and presence that a healing relationship requires. There’s no app for that, no magical, exponential technology, no elegant hack.

There are two people. Acknowledging one another’s human potential and frailty. It may be challenging to scale, but it’s the most ancient and elegant model of them all.

To learn even more about Raul, read this excerpt.