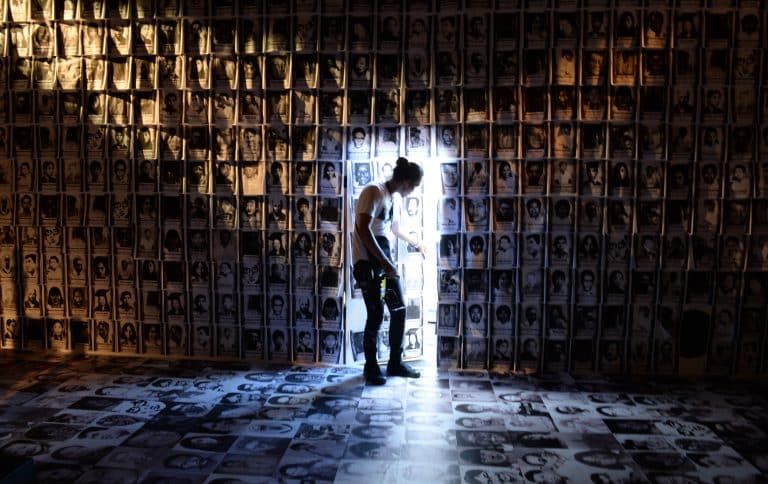

Emily O'Dell co-teaching a yoga class to refugees in the southern suburbs of Beirut, Lebanon. Image by Emily Jane O'Dell, © All Rights Reserved.

Refugee Yoga in Beirut

Our little yoginis looked bored. They didn’t care about karma yoga—the path of service and self-transcending action. I wanted to talk about Martin Luther King and Mother Teresa, visionaries who could see the divine in all of creation and encouraged the world to cultivate tolerance for all humanity. But the girls just wanted me to stop talking and stand on my head.

I hadn’t done a headstand since I’d risen from my wheelchair. I wasn’t sure what was more difficult — the fight to get insurance to pay for the chair on time or the jihad to walk again on my own two feet. My personal struggles, however, could not compare to those of the yoginis lying on the mats beside me—the refugees whose families had fled their homes in Palestine and Syria during war to escape to the country next door.

As we pulled into the lot of the refugee camp in the southern suburbs of Beirut that morning, the mist on the graffiti mural of Arafat was making him cry. “Look. They even have VIP parking,” my friend Samar said, pointing at a tent pitched over several busted up cars.

Loaded like donkeys with our new yoga mats — still in the plastic wrap — we hiked up the hill.

“Every time I see the wires, for some reason, it still really gets me,” she said, as a hazardous web of wires swung over our heads. A group of ten girls — most in hijabs — rushed over to grab the yoga mats spilling from our arms. Decked out in their colorful headscarves, purses, and jeans, they were dressed more for a Saturday outing on the town. How do you dress for yoga, I thought, if you don’t know what it is?

“Show them your headstand,” Samar said, aware that my freakish levels of flexibility had made reaching the highest levels of ashtanga a breeze. But with no natural resistance to stretching, I’d been deprived of the physical challenges that breed transcendence — until my hips slipped from their sockets one day in Turkmenistan.

“Do a headstand,” the girls said, egging me on. I hadn’t been expecting to do any yoga poses on command. I’d only agreed to tag along as a spotter. Having not done yoga for a year, I accepted that I might fall over and look like a fool.

Planting my head gently on the mat, I activated uddiyana-bandha and, ever so slowly, began to lift my legs to the sky.

“Look, look — I’m doing it,” I wanted to say, like a child. As I showed the refugees their first yogic head stand, I realized it was, in a way, my first one too.

When I descended from my headstand, the girls were no longer watching. Maryam was the first to grab her mat and position it against the wall. Placing her hijab on the mat, she soon found herself looking upside down at an upside-down world. As the other girls followed her lead, I was reminded of a sermon from many years ago when I attended a historic Black Baptist church in Providence, Rhode Island while a student at Brown.

The sermon was on the Gospel of John 5:8, the story of a disabled man who came to Jesus to be healed. And Jesus said to him, “Get up! Pick up your mat and walk.” Even after all these years, the reverend’s spirited oratory punch hadn’t left me. “Pick up your package, and walk! Ain’t nobody else gonna do it for you, so pick up your package, pick it up and walk,” he said.

Before long, all the girls except for Hiba had their toes pointed to the heavens and were seeing the world in a whole new light. Hiba’s head was on the mat, but she was stuck. “Watch your neck,” I said, “it’s got too much tension. Relax it, like this.” As Hiba loosened her neck and began to take flight, I noticed that Maryam was still hanging upside down like a bat, but her face had disappeared. Lifting the white veil shrouding her like a mummy, I uncovered the ecstatic smile of a yogi.

Though every yoga class ends in shavasana, it’s unsettling to lie in corpse pose in a refugee camp, with a war next door. Yogis says the corpse pose is the hardest of them all because the body must be fully at rest. As an Egyptologist, the corpse pose has always been my favorite, but not here. Not when there are daily body counts being tallied, not when we all feel like sitting ducks.

For me, yoga used to be about mastering advanced poses and showing off my muscular arms. Today, it’s about a little girl named Maryam, suspended upside down in a headstand while a country teeters, like her, on the brink of war. It’s about visiting refugee children with TB and chickenpox — children who jump over puddles laced with wires, smiling despite having seen their siblings slaughtered in war. It’s the beautiful Syrian woman weeping in my arms, our bodies melting into one in the folds of her abaya. It’s the little boy who, when I asked how old he was, replied “Elef!” A thousand. In a camp where a day must seem like an eternity, his answer didn’t surprise me.

Can a yoga class really make a difference in the midst of a war zone? I don’t know. But I do know that to have a body that moves, and a home of one’s own, is a blessing of the highest order. “Yoga,” by definition, means “to join together.” And this is what we’re doing — in mind, body, and spirit — for a moment of peace. And that, for me, is enough.

In a spiritual sense, we’re all refugees longing for home. Like them, I too am far from home. But unlike me, they don’t have the luxury of a house on the sea, with heat and electricity. And so it is from this abode that I pick up my pen and donate these words. I never really leave the refugee camp, or the refugees. How could I? They are my true yoga teachers, guiding me from deep within my heart, no matter where I live or how far I travel. In a way, really, we are all guiding one another home.