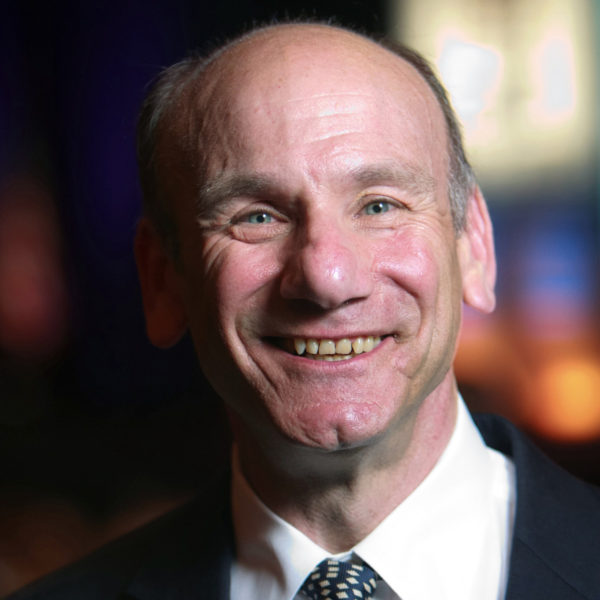

Image by Peter Tandlund/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)..

Wrestling with the Questions, and Why It Matters So Much

I began making a list of what matters to me. Intellectual curiosity. Climate change. The First Amendment. My family. Giving back. One friend said to me, I know what I’d say: Money. Another friend told me: Those talks can be surprisingly honest.

That got me thinking. What’s the most honest answer I could give?

Right then, I knew. I had to come out. I had to say a three-letter word, beginning with G.

God.

For an academic, saying something good about God can be one of the last great taboos. So let’s break it. I’m talking about my relationship with God and no-God. You know that campaign, It Gets Better?

Well, my message is, It Gets Different. Sometimes you don’t even see the difference coming. I sure didn’t.

It was tooth-grinding that got me back to God.

I didn’t know I was on a spiritual path at the time. I began meditating for the same secular reason that millions of others have taken it up: stress reduction. I couldn’t face wearing a night guard to protect my teeth from stress, and the alternative I stumbled onto was meditation. I thought I was just learning a practical technique, picking up a little mind-body medicine. If meditation could help people facing terrible things, like cancer, why not me and my molars?

I got more from mind-body medicine than I bargained for. I got religion.

Stress, a defining disorder of our era, may yet turn out to be helpful to our species, serendipitously leading a ragtag band of agnostics and secular humanists, the nonbelievers and the lapsed, clench-jawed baby boomers and frazzled millennials, to reconsider their verdict on God.

I’m a boy in that ragtag band — a nice Jewish boy from Newark, New Jersey.

If our neighborhood — the Weequahic section of Newark, where Philip Roth’s characters live — harbored any Gentiles, I never knew it. The basement of the Orthodox synagogue where I attended Hebrew school from the time I was seven was just down the corner. The language in my immigrant family was Yiddish. Interfaith marriage was widely believed in our community to be a mortal sin, grievous enough to drive parents to sit shiva — to go into mourning — for a child.

I went to Rabbi Engel’s classroom three afternoons a week, plus Sundays. Like many children in the first flush of religious education, I soon became a zealot. I took the Torah — the Hebrew Bible — as literally as it was taught. The coherent cosmology, the unambiguous rules, the terrible justice meted out: all this structure and certainty held enormous appeal.

I knew who God was — Adonai, the Ruler of the world, the Knower of my secrets, the Judge of my fate — and I was terrified of Him. I made promises to Him, broke them, begged Him to forgive me, redoubled my ardor.

To be sure, I didn’t actually have the experience of God.

What I had was the experience of fear, and a God-fearing 10-year-old fundamentalist I fervently became.

This created some problems at home. Now that I knew the rules, I felt it my duty to police them. One Sunday, when we went to Ming’s Chinese restaurant for lobster Cantonese, I wanted to know why it was okay for us to eat trefe — forbidden food like shellfish.

“We keep kosher at home,” my mother explained, whispering, so the other Jewish people at Ming’s eating trefe wouldn’t hear.

“But Rabbi Engel says—”

“Don’t tell Rabbi Engel.”

“But why—”“That’s how we do it in our family.”

Yes, she admitted, later that night, sitting on my bed, after I had done with crying, yes, the Torah does contain 613 commandments, but only certain kinds of Jews obey them all. Fanatics. Our kind, the people of Schuyler Avenue, have made a little accommodation to modern life. We don’t live in the old country any more.

Thus was I introduced to the notion that the Torah was more like a buffet of options than an all-or-nothing proposition. My mother saw no slippery slope between her selective enforcement and moral anarchy. As long as people like us kept certain key commandments inviolable — Thou shalt not marry a shiksa, a Gentile girl, for example — our Jewish identity was intact.

I felt betrayed. It seemed to me that if one rule could be broken, all of them could. And so, perhaps inevitably, I rebelled. As my vision widened, as teachers and books and television and other kids ventilated my thinking, as puberty arrived, I began to question everything.

I confronted Rabbi Engel. If man descended from algae, how could Genesis be true? He patiently explained that some things — the idea of a “day,” for example — need not be understood literally. But Rabbi, I pressed, if one part of the Torah can be explained away as a metaphor, why can’t any other portion be waived as well?

It was like fighting with my parents about keeping kosher, only now it was the rabbi himself playing loosey-goosey with absolutes, and this time I felt not betrayal, but vindication.

I became the Voltaire of Schuyler Avenue, skewering everything on my skepticism. If God is good, I asked anyone who would listen, why did he let the six million die? If I can pick and choose among the commandments — if I’m free to eat shellfish — why isn’t another man free to murder? The answers confirmed my suspicion that religion was a con job, an iconoclasm also spurred by my devotion to Mad Magazine, the South Park of its time.

In high school, in AP physics and chemistry I learned the real rules that governed the universe: not scripture, but science. In AP biology I learned that life randomly emerged from an organic soup stewing for a billion years — no Creator required, thank you very much. In AP history I learned how much blood has been stupidly spilled in the name of an imaginary Deity.

By the time I arrived at Harvard, though I continued to eat matzoh on Passover and fast on Yom Kippur, these were acts of solidarity with my cultural and genetic heritage, not worship of my people’s God.

Harvard, from which I would graduate summa cum laude in molecular biology, completed my secularization. This is not a criticism. If Harvard had made me a more spiritual person, it would have failed in its promise to socialize me to the values of the educated elite.

Those values were, and are, secular. They enshrine reason, analysis, objectivity. The advance of civilization lies in the questioning of received wisdom, the surfacing of hidden assumptions, the exposure of implicit biases.

This view is not the product of a left-wing conspiracy to undermine traditional values; it is the inevitable consequence of an Enlightenment that began with Galileo, Descartes, and Newton… and a modernity launched by Darwin, Marx, and Freud… and a post-modernity postproduced by Lévi-Strauss, Foucault, and Derrida.

The prized act of mind in the Academy is the laying bare of hidden agendas. Nothing in culture is neutral. Nothing is what it seems. The educated person knows that love is really about libido, that power is really about class, that religion is really about fantasy, that altruism is really about self-interest.

At bottom, all values are relative to their communities. At bottom, everything is political. At bottom, everything is contingent, driven by the mores of time and place, reducible to its origins in evolution and history.

In every field, this view was being pursued to its postmodern conclusion; all the leading theorists were busy committing epistemological suicide. Look at the ideas that bit the dust: in aesthetics, the notion that there are objective standards of good and bad; in literary criticism, that there are right and wrong ways to interpret a text; in law, that justice is beyond politics; in psychiatry, that there are fixed distinctions between normalcy and madness; in anthropology, between savage and civilized; in art, between high and low.

The project of thinking, I came to understand, was to dismantle its own foundations.

Even science itself was under siege. The great achievement of the philosophy of science, I learned, was to reveal that science is saturated with politics. When scientists find evidence that conflicts with a paradigm, and they have to choose between discarding the evidence or discarding the paradigm, they make that choice not by applying objective rules, but by deciding who among their peers they trust.

By my last year in college, I was no longer a scientist. I was searching for answers elsewhere. In Dostoevsky, in Nietzsche, in artists who had looked deeply into the human condition, what they found, what I found, was the Abyss. We are alone. Life is absurd. We shiver in the pointless void, haplessly contesting the meaninglessness of our fate. Our yearning for purpose is doomed. It is our burden to live in a time when our minds have deprived us of our capacity for soothing self-delusion. In other words, everything sucks. In other words, nihilism.

A nihilist who doesn’t kill himself is lacking in followthrough, but not in analysis. Though I had thought myself out onto an intellectual ledge, I didn’t jump. I kept going — as many people keep going — by making an armistice with the ways of the world. Call it nihilism lite. It sounds like this:

If everything does come down to politics, it’s still better to know that, so that we can fight for our side’s values, than to pretend otherwise, and be the victim of their side’s values posing as transcendent norms. Even if love can be reduced to evolutionary biology and neurotransmitters, it can still feel like it makes the world go round. Even if values aren’t God-given, moral conduct is still possible. We abide by Kant’s categorical imperative: The rules we should follow are the ones we’d want to be universal laws.

This works. It’s practical. It helps countless people get out of bed in the morning.

But it is an armistice, not a peace. Existential desperation is never far away. It is difficult to face mortality without God. It is hard to tell children that the universe is indifferent to them. Even for the most fortunate, it is painful to confront the night thought, Is this all there is?

No wonder religious fundamentalism is booming. Fundamentalists know who they are and where they fit. They have no difficulty recognizing evil. They are confident that theirs is the one true way. We have Kant; they have God. They live by the literal word of the Bible; we live by its poetry. They are commanded; we are merely moved.

But fundamentalism is not a rational choice. It is not willed by the intellect; it is a mysterious visitor. I have often daydreamed about that visitor. If the God of the Lubavichers or the Satmars were to appear to me and demand obedience, I suspect I would gladly give it. But I am no more capable of partaking in Hasidic ecstasy than I am of heeding the biblical injunction against mixing linen and wool. It is not an option for me. Once the mind thinks some thoughts, it cannot unthink them.

This is the sadness at the heart of secular lives. No one wants to live in a pointless, chaotic cosmos, but that is the one that science has given us. We may yearn for the divine, but hipster neo-Dadaism is the best we can do. Everything’s ironic. Everything’s a joke. But inside, it can feel awful. The things you want a God for — an afterlife, a comfort, a commander — seem unavailable.

That’s where I thought I would spend my life: a cultural Jew, a closet nihilist, searching despite myself for something transcendent to fill the hole where God was.

I found that something in my dentist’s chair.

When he told me I ground my teeth, I denied it. I didn’t think of myself as unduly stressed; I had long ago decided that life is a roller coaster. Stress comes with the territory, and you deal with it, even thrive on it. That I was grinding my teeth suggested I was kidding myself. A part of me, beyond my conscious control, was having a hard time, and taking it out on my molars. Wearing a night guard would be like admitting defeat — letting my unconscious torpedo my equanimity.

“You’d be surprised how many of my patients use them,” my dentist said. “A lot of people hold tension in their jaw. It’s nothing to be ashamed of.” I imagined myself reaching to my night table for my night guard. It made me think of the false teeth my Russian grandmother kept in a jelly glass by her bedside.

“Are there any alternatives?” I asked him. He pessimistically suggested meditation.

What appealed to me about meditation was its apparent religious neutrality. You don’ t have to believe in anything; all you have to do is do it. I had worried that reaping its benefits would require some faith I could only fake, but I was happy to learn that 90 percent of meditation was about showing up.

The spirituality of it ambushed me. I saw no visions, heard no voices, felt no caressing hand. But unwittingly I was engaging in a practice that has been at the heart of mysticism for millenniums. I’d read that people of all faiths had learned to meditate without violating their personal beliefs. At the time, I took this to mean that there was nothing inherently religious about meditation, which suited me just fine.

I was wrong. The reason that meditation doesn’t conflict with religious beliefs, whatever they are, is that it shares a highest common denominator with all of them.

To separate 20 minutes from the day with silence and intention is to pray, even if there’s no one to pray to. To step from the river of thought, to escape from monkey mind even for a moment, is to surrender to a transcendent realm. To be awakened to consciousness empty of content; to be thunderstruck by the mystery that there is something, rather than nothing; to be mindful, to be present; to be here, now: this is the road less traveled, the path of the pilgrim, the quest.

When I am asked whether I believe in God, I say that belief is the wrong word to use. I experience God. God may be the wrong word to use, too.

What I experience — no, not always, and sometimes not at all — is known to every mystic tradition. It has been called Spirit, Being, the All. It is what the Kabbalah calls Ayin, Nothingness, No-Thingness. It’s ineffable. It’s why Jewish mystics call God ha-zeh — the This. You can point to it, but you can’t describe it. You can sing it, but you can’t say it. It is better conveyed by silence than by language, by dance than by liturgy. And it is the experience at the heart of all contemplative practices, whether you’re looking for it or not.

The All is a long way from Newark, and silence is a long way from Harvard. As am I.

I used to think scientific materialism was the apex of human evolution. I used to think nihilism was the tragic price of progress. I used to think the soul was just a metaphor, a primitive name for dopamine. Now I think thinking isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

What matters to me and why?

What’s mattered most to me in my life is… wrestling with that very question: What matters?

And why? Why does wrestling with that question matter to me so much?

I can’t help it. I have to. That’s the thing about experiencing the ineffable. That’s the thing about the This.

Share your reflection