adrienne maree brown

On Radical Imagination and Moving Towards Life

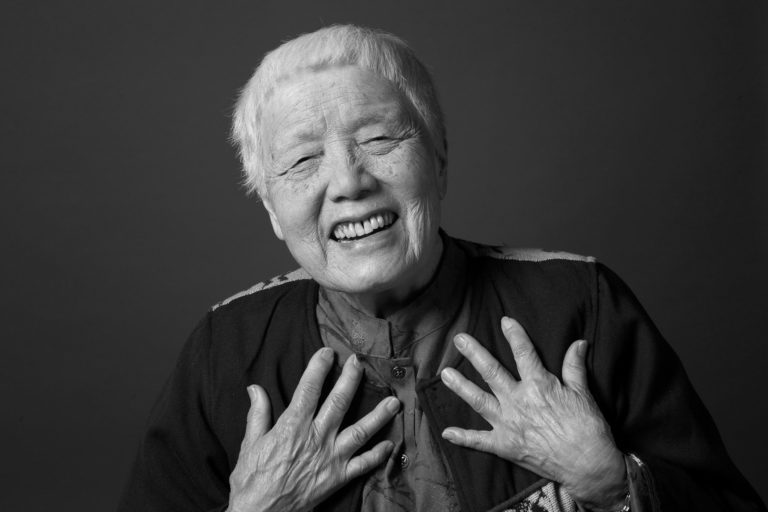

The wonderful civil rights elder Vincent Harding liked to look around the world for what he called “live human signposts” — human beings who embody ways of seeing and becoming and who point the way forward to the world we want to inhabit. And adrienne maree brown, who has inspired worlds of social creativity with her notions of “pleasure activism” and “emergent strategy,” is surely one of these.

We’re listening with new ears as she brings together so many of the threads that have recurred in this season of On Being: on looking the harsh complexity of this world full in the face while dancing with joy as life force and fuel and on keeping clear eyes on the reasons for ecological despair while giving oneself over to a loving apprenticeship with the natural world as teacher and guide. A love of visionary science fiction also finds a robust place in her work and this conversation. She altogether shines a light on an emerging ecosystem in our world over and against the drumbeat of what is fractured and breaking — the cultivation of old and new ways of seeing, towards a transformative wholeness of living.

Image by Cyan Lin, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

adrienne maree brown is the author of several influential books, including Emergent Strategy, We Will Not Cancel Us, and Pleasure Activism. More recently, she has published Maroons, a work of speculative fiction, and she co-edited the anthology Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction from Social Justice Movements. She also co-hosts the podcast How to Survive the End of the World. And, a special heads up: in late summer 2024, adrienne maree brown will publish a phenomenal new book — Loving Corrections. Image by Anjali Pinto.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

Krista Tippett: The wonderful civil rights elder Vincent Harding liked to look around the world for what he called “live human signposts” — human beings who embody ways of seeing and becoming. That point the way forward to the world we want to inhabit. And adrienne maree brown, my guest this hour, is surely one of these — she models ideas that bring worlds into being with winsome language like “pleasure activism,” and “emergent strategy.” And I’m listening to her now with new ears as she brings together so many of the threads that have recurred in this season of On Being: looking the harsh complexity of this world full in the face while she dances with joy as life force and fuel. Keeping clear eyes on the reasons for ecological despair, while giving herself over to a loving apprenticeship with the natural world as teacher and guide. A love of visionary science fiction also finds a robust place in her — and in this conversation. She altogether shines a light on an emerging ecosystem in our world over against the drumbeat of what is fractured and breaking: inspiring us to cultivate old and new ways of seeing, towards a transformative wholeness of living.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

adrienne maree brown is the author of several books shaping new generations. She lived for many years in Detroit and now lives in Durham, North Carolina, where she was as we spoke.

Tippett: Hi there.

adrienne maree brown: Hi. How are you?

Tippett: I’m good. It’s Krista. I’m so happy to meet you. So honored to have you here.

brown: It’s so good to meet you, Krista. Your voice has been in my ear.

Tippett: Oh, that means a lot. That really means a lot. You know, [laughs] I kind of — well, first of all, I’ve had a crazy few weeks, and I’m kind of getting back into my body. And then, so — we both love science fiction, so…

brown: We certainly do.

Tippett: …sometimes I talk about my interview preparation technique as the “Vulcan mind-meld approach” [laughs] …

brown: [laughs] Yes — very deep.

Tippett: … because I try to kind of — my thoughts to your thoughts, your mind to my mind. So I just try to get inside, not just what somebody knows or thinks, but how they think. And I have to say, I mean, that has been just so incredible…

brown: Oh, yay.

Tippett: …just approaching [laughs] your mind, your thoughts. And I have all these notes, including a lot of your own words that I want to just offer back to you and see where you dive from there. But I also really feel like this is going to — like this interview will be characterized by emergence. It just feels —

brown: Oh, yes.

Tippett: Right? So, yeah.

brown: I was going to prepare myself. I was like, let me prepare. I’m going to talk to Krista. And then I was like, “Oh no, you can’t prepare. [laughs] You have to just be.” So then I just decided to have lunch. [laughs]

Tippett: I’m so glad you did that, and, well, I would love to ask you this — I’m so curious, actually, to ask you this question that I’ve asked so many people — how you would start to speak about what the spiritual background of your childhood was, however, you would describe that, looking back now.

brown: Yes. I love my spiritual childhood, actually. [laughs] So I think the big-picture way to think about it maybe is, I was born into a household that was at the transition point, like on the horizon, between an evangelical Christianity that was very obligatory and very, kind of, shame and judgment, God is going to punish you, and that kind of religiosity of spiritual practice, but we were at the horizon to a more direct and action-based, practice-based spirituality. And my parents were an interracial marriage in the ’70s, mid-’70s.

Tippett: Your mother was white and your father was Black, and they met in South Carolina.

brown: Yes, mother white, father Black, and met in South Carolina, fell in love at Clemson University, but they were making a whole world unto themselves. And so we went to church. My dad was in the military, and we were often in nondenominational churches on the base, but we were always really encouraged to think and to ask questions; we were taken out into nature — my parents loved to take us to parks and take us to the mountains and show us, like, Look at the world. If I was going to say what are the most persistent spiritual practices, it was probably gratitude and compassion; we were always like, “Wow! We get to be here. Wow. Just be amazed by this world, and travel and be curious and see it all.” And then when people would mistreat us, or when we would encounter intense racism and other things, there was so much — there was a compassion of, Oh, that’s on them — [laughs] you know? That’s — they’re struggling. They’re struggling, but we’re safe. We love each other. We’re good.

Tippett: Wow, what strength. What strength that was that you were endowed with. You wrote something — I believe this was during the pandemic, on your blog — about your grandfather, your white, Christian, evangelical grandfather.

brown: Fred Mathis.

Tippett: And you said — I just want to read this back; it was so beautiful. He passed away — is that right? — just in this time. You wrote, “there was a long time where i wrestled with how to relate to this 6 foot 2 white … Christian evangelical hunting horse riding man. i, his thick interracial queer outspoken radical granddaughter, who grew up traveling the world. but we made our peace with each other a while ago, beyond all of our labels. we found common ground in the fact that we were led by our spiritual experience of the world.” So just say a little bit more about that, what that generative spiritual experience was that you shared with him.

brown: So he grew up Bible-thumping. You were expected to go door-to-door and really make sure everybody knew about Jesus and that everybody had an opportunity to get on board. And he gave everyone — actually, at his funeral, people were — everyone was holding up their copies of the “700 promises” that Jesus made to us all. He had this little book that he would buy for everyone.

So when I came out to him, when I came out to my grandparents, they initially kind of cut me off. They were like, don’t come around here no more. But my grandfather — the same as when my mother came to him and said, “I’ve married a Black man” — my grandfather, his root in love and his root in Christianity was deeper than even the socialization of hatred and small-mindedness. And so that always came through. So I knew — I was like, if I can just look at him if I can be in his presence, I know that he’ll sense my spiritual well-being. He had a real ability to tell that.

So I went to see them, down in South Carolina, after a period of staying away. And it was awkward, it was hard, but he immediately — we were just sitting together. He took me and he hugged me, and we sat together and we talked. And we just, at one point just stood up and were looking at each other, as children of God. That’s the only way I can describe it, and I said to him, “I am a child of God. I am a divine being, and the work I’m doing is divine work. And it may look different from what you’re doing, but I think it’s the same work.” And he just held me. And there was such peace between us. There was such peace between us.

And so when he passed, I knew we were good. I knew we were at peace, and I felt a blessing in that; that he was able to see that in me across all the barriers that his shaping had set up that would make it so that was hard to see.

Tippett: You also — I think you wrote somewhere that he was also a Trekkie, which helped.

brown: Well, no. So he — so my grandfather was like —He was a man of Earth and of God. But my dad…

Tippett: Your dad.

brown: …a Black man, my dad was the Trekkie. My dad was like, We’re watching Star Trek. That’s the future. Let’s go there.

Tippett: And Octavia Butler, the science fiction writer, is such an influence on you. Some people will have read her, some won’t. But so just knowing that, talk a little bit about what she worked in you.

brown: So she was a science fiction writer, and at the time that she was writing, she would always be like, I’m kind of the only one; the first of what she was, a Black woman writing science fiction. She didn’t want to be the only one, and she expressed that, as well. But she really looked around and there weren’t people, that she could see, doing it. And when I read her work, I think what opened up in me was all this possibility.

So until reading that, I had been reading Philip K. Dick and — I’d read all the classical — William Gibson and all these other sci-fi — I loved it, you know; I love Star Trek, I love Star Wars. But there was always this white, male protagonist, and I would try to slot myself into [laughs] the protagonist role, or find a place for myself in the storyline.

And then Octavia, I open up her books and the protagonist is a Black girl. And both the Blackness and the youth matter here, that it was like, she was writing people who were 15 years old and who already had a sense of destiny and a sense of, the world needs to change, and I’m going to shape that. I’m going to be a part of that. And she was very solution-oriented in her writing, she was very practical in her writing, so everything is very clear. You’re not going to read Octavia and come away confused. You’re going to read it and be like, “Oh, I should pack a bag so that I’m prepared for when the apocalypse comes, and here’s what I should put in it. And I need to figure out how to be a human with other people because I don’t know who I’m going to end up in the apocalypse with. So I need to be good at figuring out how to be with whoever I end up there with.”

She wrote so many stories where the main message was like: change is coming. You can be prepared for it, and you don’t have to be a victim of it; you can actually shape it. So she opened all of that up for me, and I kept returning to the work, over and over again.

She also really opened up that you can look to nature as a teacher; that the natural world is up to a lot of things, and we are natural. And so anything that’s happening out there can happen in us. [laughs] And we can coexist, and we can be symbiotic, and we can collaborate.

And her disappointment in humanity also was really comforting to me. [laughs] She was just like, wow, we have this amazing, awesome Earth, and we are just fumbling the bag because we’re so obsessed with using our intelligence to enact hierarchies over each other. And I was like, she gets me. [laughs] She sees what I see.

Tippett: And how old were you when you started reading her?

brown: I think I was like 17.

Tippett: Oh wow, okay.

brown: Seventeen, coming into college, I found her books at the Strand Book Store in New York.

Tippett: There’s this passage from The Parable of the Sower, “The Book of the Living, verse 19.” And it’s — “All successful life.” And it — I’ve seen you work with the words, with the language and the ideas that are at the core of your work, also kind of emergent from this passage, right? And so “[a]ll successful life is —” and I just love that framing.

brown: All successful life, yes.

Tippett: It’s what could we be moving towards, right? What — how does successful life function: “is / Adaptable, / Opportunistic, / Tenacious, / Interconnected, … / Fecund. / Understand this. / Use it. / Shape God.”

It feels to me like — and you sometimes speak about — what is it you say? — that visionary fiction is a core principle in your work. And it seems to me that what you’re getting at there is a core value of imagination, and understanding the power of imagination in making the world and remaking the world.

brown: Well, you know, I want to shout out my friend Walidah Imarisha, who named visionary fiction. And I was obsessing over Octavia, and she was, also. [laughs] And we found each other. And we pulled together this anthology called Octavia’s Brood. And in that process, I started the work of emergent strategy, started to listen to what is up with the natural world; what can it teach us about how to be humans and how to be humans in a better relationship with each other? And what I realized is it is the work of radical imagination to do so, but also that we’re living inside of imaginations that other people told us were true and told us, this is how the world is.

And I always uplift my friend Terry Marshall. He was the first person to say this to me, that we’re in an imagination battle, which just blew my mind, and I think about it often; that we live in this abundant world, and we’ve been told it’s scarce. And then we’re given all these stories of scarcity. And because of that scarcity, we have to fight each other constantly. We live in a world where there’s actually no superiority based on what we’re born into, whether it be skin, sexuality, gender, any of that, but someone has imagined superiority, and someone has imagined it into a structure that we now all —

Tippett: There’s no natural — coming back to that language of what is “natural,” that there’s no “natural” superiority in these things.

brown: No, everyone’s just doing their job. It’s just like, you’re just being a mushroom, you’re just being an oak tree, you’re over there being a daffodil and a sparrow, and we each have work to do. Same amongst humans — we’re just bags of water with the capacity to reason and spiritual callings. [laughs] And we all have that.

But if we imagine that we’re supposed to be divided and we imagine these constructs to live inside, we can get very committed to those constructs. And then our imaginations can get very limited, because it’s just like, oh, what can I dream? For me as a Black, queer woman, it’s like, what are the dreams that I can dream inside of the boxes of Blackness and queerness that someone else has constructed for me?

And that’s never felt like enough room, because I’m a spirit, [laughs] you know? I’m this massive energy like all humans are. So, so much of the work for me, of radical imagination is: what does it look like to imagine beyond the constructs? What does it look like to imagine a future where we all get to be there, not causing harm to each other, and experiencing abundance? And what — how do we make it compelling? Is it — do we tell the right kind of story? Will that make it compelling? Do we need to write new music to make it compelling? How much conflict is necessary to have a compelling future, since humans seem to love it? I’m like, is there a right place for it? [laughs]

Tippett: I think your point is that we can also do it well, or badly; that right now we do it very badly. [laughs]

brown: Oh, you know, we do it badly, but it’s all happening at the same time. So there’s also beautiful imaginations unfolding. And I come from 25 years of being part of movement work where I think movement workers tend to have the most beautiful imaginations.

Tippett: You’ve even spoken about that organizing can be treated like time travel.

brown: Yes, it is.

Tippett: Say some more about that. What does that mean?

brown: Well, we very much have said all organizing is science fiction, right? It’s like, we are reaching into the future, we are trying to project what we can imagine into the future, and organizing is a way of saying, we are going to put our hands directly on the future. We’re not going to sit by and let injustice perpetuate. We are going to get involved and shape it into something that we can all be in. But it’s also time-traveling backwards. So much of organizing is looking back, at what did our ancestors try, what did they learn, what were they up to? What was Harriet Tubman doing? We’re obsessed — I’m obsessed with Harriet Tubman. I’m obsessed with what was it like to walk in her shoes and to face her fears? So I always want to reach back and be like, Okay, well, now what is the Harriet Tubman activity to do in this time? And what does Harriet Tubman up to in 2063, because there’s always someplace that needs justice and liberation.

Tippett: A minute ago you were talking to me about your childhood, and you said your parents having an interracial marriage in the ’70s, they were making a world that didn’t exist. And that’s also…

brown: Yes, very much so.

Tippett: …and that’s what visionary fiction does, that’s what fiction does, and then I hear you saying that’s what organizing does.

brown: And there’s a way — just like I think my parents ran into, it’s like, you have to bring that imagination into relationship with reality, and that can be devastating. [laughs]

Tippett: You have to work with what’s there, as well.

brown: It’s like, yeah, there’s something — being with what is and then figuring out how do we make more possible.

[music: “Basketliner” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I feel like your work and your writing, your activism, and really the conversation, the wider ecosystem of conversation and action and change and imagination that you’re part of, is — there’s a vocabulary. There’s really a lexicon that’s being unfolded. And it’s words and ideas and practices and — so I think one of the things I want to do in this short time we have is to kind of lay some of that out. So obviously, emergent strategy is at the core of it, and you said a minute ago, I think, that it was reading Octavia Butler that you first — that that phrase came to you. But talk about what it means to put those words together, “emergent” and “strategy.”

brown: I love talking about this. [laughs] Maybe I’ll never tire of it. But I’ll also try to be brief.

So the word “emergence,” for people who don’t know, the definition I work with comes from Nick Obolensky. And it’s emergence is the way complex systems and patterns arise out of relatively simple interactions. So birds flapping their wings, birds in a flock together, is a relatively simple interaction; but birds all doing that together and avoiding predation can become the most complex, gorgeous patterns of murmurations, migration, survival. So we’re all emergent beings — humans are an emergent species amongst emergent species. And the strategy part comes in — I was in a movement moment where everyone was talking about who was strategic: who’s the most strategic, and who’s creating a strategic plan, and all of this. And I realized that there was no specificity. You could be strategic and still causing a lot of harm.

Tippett: [laughs] That’s right. You can — right.

brown: I was like, you can be a hierarchical, strategic person.

Tippett: All change is not progress.

brown: Exactly. So I was like, we should be more precise. And I think what we mean by strategic is: able to adapt to changing conditions, while still moving towards our vision of freedom and the future and being in that practice. So that’s what emergent strategy is. It’s like, how do we get in a right relationship with change that allows us to harness and shape things, towards community, towards liberation, towards justice? And we’ve been experimenting now for five years — the book came out five years ago — and we created a little institute that is practicing things.

Tippett: The Emergent Strategy Ideation Institute, right?

brown: Yeah. [laughs] And that ideation part is so important to me, that it’s like, we’re still learning. We’re trying to learn, fundamentally, how do humans become compatible with the Earth again, because right now we’ve kind of fallen out of her — out of alignment with what she needs.

Tippett: I was looking on the website of the Emergent Strategy Ideation Institute, and that notion of acknowledging the real power of change and embracing — finding practices and responses and visions and plans that embrace complexity, interdependence, and transformation, and also noting that “[t]his strategy has been observed from the natural world and is both ancient and constant.” So even in this short conversation you and I have had, you’re always locating yourself within; within an ecosystem of teachers and role models and language. And for you — and this feels to me like such an incredible thing that’s happening in the 20 — I mean, this language of ecosystem is about 100 years old, and I think it takes us about 100 years, [laughs] as a species, to start to internalize a true paradigm shift like that. And that — so your teachers, also, are in the natural world. They are mushrooms and dandelions.

brown: Absolutely. And I feel like the more mature I get, the more I’m able to receive the medicine or wisdom directly. So I feel like when I was first starting, I was like, let me go read Paul Stamets and see what — because he knows about mushrooms, and I don’t. And nature was such a mysterious place to me; I was like, you’re supposed to be scared of it. And now I feel like, oh, I am of it. And I feel healthiest when I am in it and around it and listening to it. And when I’m doing all those things, I receive so much from it. There’s so much — even at the basic, basic level of taking care of a houseplant — for years, I could not keep a houseplant alive. And I would joke about it, but I also felt devastated. [laughs] I was just like, I can’t even keep a simple thing alive on this planet?

And then it clicked. Then I’m like, oh, it’s caring for something alive.

Tippett: Oh, I see.

brown: I had to demystify it. It’s not like I just do one thing, one time, and it’s sorted, which is very much how capitalism wants plants to be present, is like, just buy a plastic one and put it in the corner. Done.

Tippett: So talk to me about the strategic intelligence of mushrooms.

brown: So mushrooms, I feel like they’re our great detoxer. They’re the ones who understand that nothing needs to be wasted; that everything can be used in some way, we just have to understand what it is. And I often think about this when it comes to our abolition conversations and our justice conversations — that mushrooms are like, this is food if we can find a way to use it. This could be nourishment. And when something breaks down in our communities, it’s actually a moment, usually, when something needs nourishing or when something is dead, when something is done, it’s complete, and it needs to be processed back into the whole. And instead of letting it go, we battle each other. And we fight and we take on shapes that maybe are gossipy or harmful.

Tippett: Can you think of just an example, a situation?

brown: Oh yeah. So in movement spaces — I worked as a facilitator for 25 years, so one of the things I saw all the time is an organization would have served its purpose, or served the initial purpose it came into existence for, and what would’ve been great and possible was to just sunset the organization, just be like, great, we did a good job. Let’s call it. Let’s learn what we need to learn, and move on. And instead of doing that, the organization was like, no, no, we need to persist. So let’s change our mission, we’ll update our mission, and here’s what the philanthropy is willing to fund. And they get contorted…

Tippett: Right. And that’s so much a part of it.

brown: …and they get contorted. And then, all of a sudden you have people fighting each other, saying, Oh, you’re not aligned with the values of this organization. You’re not a true radical. All kinds of stuff comes out from that. It’s like, actually, all that needed to happen here was we need to let this thing go, because it was complete, and figure out what the next step of work is. And those next steps might be different. So some of the people who create, for instance, a radical direct action organization, if you win your campaign, maybe you go on and say, What’s the next place that needs action? And that might be a different structure. But some people might be like, we need to switch tactics and move into governance now. We won something, and now we need to go govern that and make sure it happens.

Those are very different callings, and sometimes they come together under the same umbrella, but we often forget that it’s like, oh, now it’s time to compost this and process it and see where else the resources need to flow.

Tippett: And I think what you’re describing is true of all kinds of organizations, right? It’s a cultural — it’s a cultural kind of bias and sensibility that we have, that if something dies or ends…

brown: Yes, that that’s bad.

Tippett: …that it’s failure.

brown: Exactly.

Tippett: And it’s an ending and it’s a beginning — it’s vitality.

brown: It’s vitality. And what you’re speaking to is the life force, right? Like mushrooms, to me, mushrooms are like, everything dies, but that’s kind of good. [laughs] It makes for a very rich world. All the richness, all that fecundity, all that beautiful miracle of life; it happens because we live in cycles, not perpetuity.

Tippett: And as you say, composts something else, right — other seeds. Other seeds are then — have their moment, have their time.

brown: Exactly. Exactly. And it’s trying to hold onto stuff and not let it die that actually puts us in precarious positions, even for our species. This is actually one of our biggest issues right now, is we’re so scared of death. And so we think about, how do we make people live forever, and how do we look young forever, and do all this stuff, instead of being like, oh, no — how do I get good at dying? How do I get to where I’ll be at peace when my time comes because there’s other generations that need to survive off of the resources of this place? [laughs] It’s in the design.

[music: “Dearborn” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I guess something that’s so on my mind, also, as I read you — because I think my focus is, or my lens on things is the human condition, looking at anything through what’s going on with the human condition, and that, also, is very much part of your world. And I feel like there’s a lot of wisdom about the human condition, and also, really, that you have to be wise about it in order to work with it and help it evolve generatively. So just drawing on what you were just saying, emergence is change, right? Someplace, you said, “Emergence is our inheritance as a part of the universe; it is how we change.” And emergence doesn’t wait for us to be ready for change, and we’re really in an accelerated moment of that right now.

But as you know, change is really hard for human beings. It’s hard for us at a creaturely level, and also, we all individually handle it in different ways at different times. And so I wanted to talk about — I feel like this wisdom is so powerfully embedded in the way you think, in the way you’re working, and so I want to go into some of the aspects of that. And one of those for me is the way you use the word “fractal.” [laughs] You said you first thought about fractals when you were — so just to bring home, again, that this is all about what happens on the ground. You were doing electoral organizing in 2004, is that right?

brown: So I was doing electoral organizing in 2004 — 2003, 2004. We’re gearing up — it’s post-9/11; we’re going to war with Iraq, Afghanistan, and we’re like, we’ve got to get Bush out of office. We have to. He’s just going to keep perpetuating all these unjust wars with all these people and not help figure anything out. So we’re doing all this organizing, and it clicked for me, in a way that I couldn’t — it’s one of those things, you see it and you can’t un-see it. And I was like, oh, we are trying to just change the top layer of this very layered cake, this very layered process, this system of governance. We think that if we just win the presidency, that then we’ll be able to change the world.

And it clicked for me that actually, it’s a fractal system. And it’s layer on top of layer on top of layer. And if none of us are practicing democracy anywhere, it’s not going to just suddenly work at the top layer. [laughs] And I got it, and then I realized — so I started asking people, because I was touring a book we had written. And I started asking people, Do you practice democracy — anywhere in your life? [laughs] Not even politically, but just in your household? Who makes the decisions about the budget?

Tippett: [laughs] What did people say?

brown: No.

Tippett: [laughs] Right.

brown: Nobody was practicing it, or if people were practicing it, they would be like, oh yeah — you know, there would always be like one really happy person who was like, I practiced it. And then I would be like, okay, in your household, you practice it. Do you practice it with your neighbors? And then they would have to be quiet. Or, do you practice it —

Tippett: Okay, that’s fascinating.

brown: There was almost nobody who was practicing it on their block or in their community or in their organizations or other places. Everyone’s kind of dodging the actual work of democracy, small-d democracy.

So then, of course, we are in this crisis right now where we cannot figure out a way past this political impasse moment. To me, what it reveals is we haven’t been practicing democracy for such a long time anyway. We’ve really outsourced almost every aspect of governance, and the only part we’ve held onto is complaining. People sit in their living rooms, they form opinions, they’re upset about stuff, they don’t do much about it, but they’re apoplectic. [laughs]

Tippett: And they also don’t know what they can do about it, right — at that mega level.

brown: Exactly. That’s on purpose. [laughs] So it’s like, trying to keep people in a place where they’re angry and they think they can buy their way out of it. That’s one of the reasons organizers exist, is to be like, actually, you can’t get out of it that way, but there are ways. We’ll have to work together to figure it out, but there are other practices.

But that’s when it clicked for me, that I was like — something about smallness, I was able to gain respect for, because I was like, every single large system or structure or network or political protocol, all of it is made up of small things — of humans either having or not having necessary conversations, and humans being willing to stand up for what is right and stand up against what is wrong. It’s all these small activities that we need to get great at if we want to actually have anything that would be a real democracy.

Tippett: This way you make the connection between what happens at the interpersonal level is a way to understand the whole society — how we are at the small scales, how we are at the large scale. One thing that I’ve been thinking about during the pandemic is that we are, each and every one of us — each and every one of our individual nervous systems has been in distress. And one way to look at our political life together, our life together, has been of a kind of collective nervous system in distress.

brown: Totally. Absolutely. It’s so wild to me right now [laughs] that people are acting like they’re rushing to get back to some kind of normalcy. And I’m like…

Tippett: We’re changed. We’re changed, right?

brown: …how are you holding your grief? There’s no normalcy, there’s no backward. There’s new. This is what’s our new reality, which will keep changing. But I have found myself so transformed by these last two years. And in some ways, there’s some aspects of it that I’m like, I never want to go back. I never want to go back to paying less attention to my relationships with other people. [laughs] I like that aspect of this. And I’m so intentional now with like, Hey, what are you doing in terms of masks and vaccines? Let’s be really intentional about how we can safely spend time together.

Tippett: Do you have a definition for — because this language of fractal comes from mathematics originally?

brown: Yeah, and the first thing that I was exposed to was actually fractals — the Fibonacci — the sequence is basically how something repeats at scale, no matter how small it gets and no matter how large it is. And it’s these particular patterns in the universe. And I felt so naughty when I started using fractal [laughs] as someone who’s like, I barely understand math, but I understand that there’s something about patterns that could liberate how we’re thinking about ourselves and each other.

But so far my friends who are in the math and science world have not completely doused me in shame, so I feel like I’m okay. But it helps people — sometimes I’ll use the language of fractals; sometimes I’ll just point to actual examples. So I’ll be like, look at a head of broccoli. Look at a fern. Look at the delta around New Orleans, and then look at how these veins and artery systems move through your system and your heart and your lungs. Look at the spiral shapes on your fingertips, and then look at the shape of galaxies. And in that way, we can begin to see there are no isolated patterns. The universe has some favorites, and they repeat, and they repeat at every scale. And then people are like, Ohh. [laughs] I’m like, yes, your body is a whole water system.

I’ve been having this thought lately, of like, oh, we’re like another body of water. There’s rivers, there’s oceans, there’s rain, there’s mist, there’s human. [laughs] There’s whale. We’re — there’s all these different formations that are all how to move water. And we’re one of them. And I find it very comforting to find myself in one of those patterns.

Tippett: And that imagery is so stunning, and it provides exactly the contrast to this worldview that you and I were raised in, that came into the 21st century — that you could elect one person at the top, [laughs] and that would change everything.

brown: And that would change everything.

Tippett: That would change everything. It was never true, but it perhaps felt a little more true in a more homogeneous society.

brown: And I also think it’s, again, in the imagination, if you are someone who would benefit from that power system, then it really behooves you to imagine the world is that way. [laughs]

Tippett: That works.

brown: I, from a very young age, was like, but I’m just as smart as these white men in my classes, and yet the same opportunities are not available to me. Can someone help me understand that? I need a logic, [laughs] because it’s not adding up.

Tippett: And there is no logic.

brown: And there’s no logic to it. And often, when there’s no logic, then that’s when you know you’re in someone’s dream.

Tippett: I was looking up, because I also mistrusted my own — I still mistrust my ability to define fractals — there’s this mathematician, great mathematician, Mandelbrot: asked to define fractals, said, “Beautiful, damn hard, increasingly useful.” [laughs]

brown: Yes. I love that. I feel like it — there’s so many things like this, I will say — when I wrote the book, I think in one of the footnotes I was like, if you’re a scientist, just try to help us make more sense —

Tippett: [laughs] Cut me a little slack.

brown: Or basically, I was just like — because especially in the sci-fi world, the science world, there’s already this battle over, is this real science fiction or fake science fiction? Does it have enough hard science in it to count as a story? And it’s like, okay, if you want to spend your life arguing about that, cool. But for me, I was like, the point for me is not to argue about the science, because science is actually still unfolding all the time, and we’re — it’s a question-based methodology. So I want to be in that method — I want to be asking questions. So I’m a scientist; so what? Deal with it, right?

But then there’s also like, don’t come to just argue the point. I feel like our whole society right now spends so much time just arguing for the sake of arguing, but I’m like, we actually need solutions. So if “fractals” is the wrong word, teach me a better one, but what I want to talk about is this.

I talk a lot about alpha versus more collaborative creatures, and I can tell when I’m with the devil’s advocate folks — they’re like, Well, what about, lions just eat everyone. Should we learn that from nature? And I’m like, no. Nature does everything. Nature does everything. There’s not — it’s actually the beauty of releasing the right/wrong paradigm. That’s not how nature is even operating, is it wrong to eat this deer? [laughs] It’s beyond that.

It’s like, if nature can show us everything, then we’re the ones who have agency. And if the goal for our species is not to cause harm to each other, we could do that. There’s models from nature. And if the goal is to make enough out of the resources we have, there’s incredible models of creatures who are doing that all the time, every day, and in very difficult circumstances. If the goal is to love each other, like Thich Nhat Hanh said, such that we all feel free, that that’s possible, well, we can see in nature who’s up to that. We can learn a lot from the Bonobo monkeys. And so on and so forth. And so it’s really asking people to be more intentional with — we were given things about the world from some people who knew less than we do now, so what do we want to hold onto, and what do we want to evolve?

[music: “A Path Unwinding” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: The language of transformative justice and resilience. Talk to me about what putting the word “transformative” there…

brown: Does to it?

Tippett: …shifts — transformative justice, transformative resilience.

brown: So for me, when I add the word “transformative” to anything, what I mean is, let’s get to the root of the problem. I think Angela Davis said — this is how she talks about “radical” — it’s like, let’s go all the way to the root.

Tippett: And that’s the meaning of the word “radical.” It’s not something on the edges, it’s what’s at the core. It’s at the center.

brown: It’s not the edges, it’s like what’s at the core, the root, the essence of it. And so for me, when I speak about transformative, it’s like, I don’t want to dance around on the surface, rearranging deck chairs. I want to get down into the root system and really understand what’s happening and what it would take to create a change if a change is needed. So for example, we have a crisis of sexual assault, a crisis of sexual harm. I don’t want to be in a situation where we punish one person at a time, which doesn’t seem to have worked at all, in terms of eliminating the problem, and yet we continue doing it and building bigger and bigger prison systems and jails and other stuff, but it’s not stopping the problem.

So transformative justice says, Actually, that’s not working. Why don’t we get to the root system, what’s causing people to enact sexual harm against each other? And can we turn and look at that without holding anything back? Can we really get honest with ourselves and look at it, because we all have some experience of someone crossing those boundaries? And we’re talking about the level — how badly did they cross them — rather than did it happen or not. That’s wild. So for me, I’m like, how do we get transformative about it? How do we go to the root system? And I learned this — there’s a group called Generation Five, who is really starting to have this conversation of what would it look like over five generations, to end child sexual abuse? And it’s like, oh, that’s a radical vision.

The other aspect of transformative is it often doesn’t rely on the existing structures or mechanisms. So in organizer-speak, we might say “the state.” It doesn’t rely on what we already think of as the solution, because we know that that’s already not working. And actually, we want to never try to solve a problem with something that we know will cause more harm, if we can avoid it.

So in a lot of our communities, say that a domestic violence incident is happening — we don’t want to solve that by calling the police, because the police in our communities tend to escalate the harm, rather than deescalate the harm; not only do we have this domestic violence situation happening, but now we have someone being possibly removed from their community, removed from their home; we have kids possibly who are going to be removed from their parents, and other things that are actually not necessary, nor are they helpful to solving the problem. So let’s not add to the problem. Let’s figure out how we can resolve it within our communities through mediation, through setting clear boundaries, through healing circles. Is there therapy needed? Let’s get as creative as we can about what needs to actually happen to stop the harm cycle.

Tippett: And this is emergent. This whole way of seeing, this whole way of imagining is emergent in our world right now. And there’s struggle around it, there are different ways of seeing, but I think perhaps more definingly, the conditions aren’t all there, right? So one of the things that you also talk about is how — that there is going to be important conflict and contradiction, that is part of the process of ending cycles of harm. And so one of the things we also have to be working on — and this goes back to our human condition — and here’s some ways you’ve talked about it: how do we fight fair? How do we struggle in principled ways? How do we practice accountability beyond punishment with each other? — because the structures are not there right now, in most of our communities, to just move to what you just described. And that’s where a lot of — and there’s all kind, there are all kinds of friction points, but that’s one of them.

brown: That’s right. Well, and one of my teachers around this is a writer and a thinker named Mariame Kaba, and she’s an exquisite human being, exquisite thinker. I want everyone to learn from her.

Tippett: How do you spell the last name?

brown: Kaba, K-A-B-A. She put out a book last year, We Do This ’Til We Free Us. And one of the things that she often reminds me of — because I think what would be so comforting to us is if we could be like, we’re going to end the prison system and automatically move to a very well-organized, centralized system where instead of everyone going to prison, you just go straight to a mediator and it’s all handled. And one of the things she points out —

Tippett: And we have the foundation for that; we just move from one place to the other, and the other one works.

brown: Exactly, we just move from one, straight to the other. And she’s like, it won’t be a huge, overarching, centralized system. Transformative justice will be a lot of us learning the skills to hold conflict within our communities, within our families, within our schools and institutions. We’re learning, ourselves, to hold it in different ways.

So she has another book out, called Fumbling Towards Repair, with my friend Shira Hassan, which I love because it’s a workbook. It’s like, okay, if I wanted to do a process like this and not have to call in punitive devices, what would that look like? And it’s like, yeah, we have to actually learn how to do something that feels new; but also, I always like to point out that this is some of the most ancient technology, also. If we listen to Indigenous communities around ways that they have resolved conflict over thousands and thousands and thousands of years, a lot of it is these same practices, and they’re still practicing them.

So it’s being in a circle. It’s listening. It’s being able to let one person speak at a time. It’s identifying what are the consequences — not the punishments, but what are the reasonable consequences, the boundaries; how to make this right; what does that actually look like? — and relinquishing the idea that we’ll all end up as best friends at the end or whatever, that kind of fairytale, Disney version of conflict mediation; instead, being with what is, the human condition. It says, It might be hard. You might never get back to that. But you can get to a just place. You can get to a just place. You can get to place where you’re not walking around carrying the anger of knowing that person; that that’s not the primary experience you’re having. It’s like, I was hurt, and now I’ve been able to move forward, and here’s what moving forward looks like, and I was able to define some of that for myself.

Tippett: I just want to read a beautiful — some beautiful sentences you wrote, so powerful, and I think this is in We Will Not Cancel Us. [Editor’s note: This passage is from Emergent Strategy] “We are brilliant at survival, but brutal at it. We tend to slip out of togetherness the way we slip out of the womb, bloody and messy and surprised to be alone. And clever — able to learn with our whole bodies the [ways] of this world.”

And the context of that was talking about how your default position is wonder, and you have to carry around a lot of disappointment and frustration [laughs] and critique with humanity, and — that you also — that that is especially true when you look at social justice movements, where you expect so much and desire so much. And you’re being honest, and you’re actually saying that from a place of love and of high, brilliant expectations, and so countercultural in this context, in which to call for accountability, to express honest critique, even to acknowledge imperfection, is leapt on as failure. So you really walked into a brave and hazardous space. [laughs]

brown: That’s right, Krista. [laughs] I always think about how I had been away on sabbatical, and the pandemic was unfolding, and I returned from sabbatical and there was like, everyone was canceling each other, is what it felt like. I had been away from social media for not even that long, and so I know this was happening before I stepped away, but I was normalized to it, because I was in it every day. And then when I stepped away and came back, I was like, oh my goodness. This is all we’re doing on the internet now? It just felt like — it just felt so intense. And it didn’t feel — it didn’t feel like what we’re supposed to be up to.

I felt like — sometimes, when I’m sitting around, I feel like I can feel — I’m not sure if it’s ancestors or future spirit or whatever it is, but I just feel this beyond energy sit with me, like, That’s not the way. That’s not the way. And sometimes there’s a, Try this, or, Take a look over here. Look up. Look at these starlings and just see if they offer you something.

And it felt like that.

I was looking at this cancellation wave, and then I was feeling for mushrooms and feeling for, who does know how to process toxic energy? Who does know how to process toxic happenings? Can we do it a different way? Could we do it with love? And can we be honest — at least honest that there’s not love in the way we’re doing it now? Because I think that was also what was hurting my heart, was people being like, Yeah, we just have to love each other — [laughs] and then we’re doing the most awful, awful dismissals and disposals of each other.

And because of my facilitation background, I was also catching some of those disposals. People would show up and just be like, Hey, you probably saw this, but I just got canceled. And almost always, I was like, I didn’t even see it. I can’t even keep up with all of it.

Tippett: [laughs] Right — you missed it.

brown: So I was like, I had no idea. But this person was devastated, and sometimes suicidal — It was having an impact. I want us to at least not pretend like it’s not having an impact, at least that. Let’s take responsibility.

And then the other pattern I noticed was, often it was people who were fairly young in movement themselves, fairly young inside of whatever their political analysis was. I’m like, I can kind of remember before you thought that. I can remember when you might’ve made the same mistake. And my heart just was like, do y’all remember that everyone was transphobic last week? All of y’all were saying this horrific stuff, and we need to unlearn this. Together, we need to unlearn it. And I think it felt like people were starting to skip the step of actually decolonizing and unlearning these oppressive systems and just being like, I’ll just punish anyone who missteps, and that’ll be how I do my action. And it’s almost like that’s people’s activism now.

And I’m like, so now we’re in a true bind because punishment doesn’t work, and it’s not a — it’s like we’re aligning ourselves with the state, and we’re depressed. We’re losing leaders left and right, because people are making mistakes and now there’s no room for making mistakes. So it just felt like a total crisis to me, that needed a different kind of attention, and because I’d been away on sabbatical, I think I was brave enough [laughs] to do it in that moment.

Tippett: What is it — you mentioned Thich Nhat Hanh talking about being free, when he says, “fresh, solid, and free.” You came back from sabbatical — Okay, do you have We Will Not Cancel Us? Do you have the little book by you?

brown: I do. I do.

Tippett: So on page 58, what you’ve been talking about on the previous page is kind of the harm that is created. But what I really think you get at here is — again, we started with the cake, the layer cake. And the election isn’t going to change very much if you just, if — it’s just the icing. And so you’re looking at the layers of this, and I feel like this page is such an acute analysis of what cancel culture — and I mean all around, across the spectrum — what it says about our culture, which is kind of the opposite of, I mean, honoring emergence. So would you just read that? “but one layer under that, what i hear is …”

brown: “we cannot change.

“we do not believe we can create compelling pathways from being harm doers to being healed, and to growing.

“we do not believe we can hold the complexity of a gray situation.

“we do not believe in our own complexity.

“we do not believe we can navigate conflict and struggle in principled ways.

“we can only handle binary thinking: good/bad, innocent/guilty, angel/abuser, black/white, etc., etc.

“cancer attacks one part of the body at a time, i have seen it – oh it’s in the throat, now it’s in the lungs, now it’s in the bones. when we engage in knee jerk call outs as a conflict resolution device, or issue instant consequences with no process, we become a cancer unto ourselves, unto movements and communities. we become the toxicity we long to heal. we become a tool of harm when we were trying to be, and i think meant to be, a balm.

“oh unthinkable thoughts. now that i have thought you, it becomes clear to me that all of you are rooted in a singular longing: i want us to live, i want us to want to live, in this world, in this time, together.”

Tippett: What’s it like to read that back to yourself?

brown: I deeply believe it. I really want us to live, and I also — I feel less lonely now. When I was writing this, I felt very alone. [laughs] I was just like, I was scared for us and for movement spaces. I want us to hold each other as so precious, and when I was writing it, that was in me, thrumming through me, such a loud longing. But I feel so much less alone now than I did when this came out, because it came out and I’ve had so many people like, Oh — yeah. [laughs] Just like, Yes, now I see what you mean. A lot of people have been called out in the time since this book came out, who’ve reached out to me and been like, I didn’t know — [laughs] until it happened to me. So that’s the main thing that strikes me now, is I feel like a lot more people are like, Oh, it’s part of the political toxicity of the moment, that we’ve been all tricked into participating in.

[music: “Kallaloe” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: Oh, one thing I do — I don’t want to end without getting to is Pleasure Activism. I think it’s been so fascinating — it’s been fascinating for me because I have this cumulative conversation. And at some point in the last couple of years, over and over and over again people kept making this very clear, very insistent connection between justice and joy. [laughter] And you — and you talk about “pleasure activism.” And so describe that.

brown: I want to make justice and liberation the most pleasurable experiences that we can have, as a species. I want to make it feel like: Ahh. When I make the best choice, it feels good, and I know it, from my bones up and out. And I know that that means a deep reclamation, especially for those of us who’ve experienced oppression or trauma; that what gets taken from us, often, is the sense that we deserve pleasure, that we know how to feel it, that we’re allowed to feel it. So one of the things I say is, pleasure is not a frivolous thing. Actually, it’s a measure of freedom; that when you are free, one of the ways you know that is that you can feel pleasure. You can feel the present moment.

For most people, it’s really just being able to feel the erotic aliveness of a moment and the erotic yes, I am alive. I’m here right now, and this is how I want this moment to go. This is good. And I have to shout out the queen mother of our lineage for pleasure activism is Audre Lorde. She wrote an essay in 1978, called “The Uses of the Erotic as Power.” And I highly recommend listening to it. You can actually listen to her read it.

Tippett: I did not know that.

brown: Yes, there’s a video clip on YouTube of her reading it. And I’m like, it’s always good medicine. It will always get you right back in your alignment. [laughs]

Tippett: And you point out, when you write about pleasure activism, that so much of how we try to organize and mobilize and even inspire, orient — and yes, in social justice work, but in journalism, as well — is about planting facts and guilt and shame, even though — I mean, if we go back to that list of — if we go back to Octavia Butler and the way you’ve talked about what is successful life, right — that does not create change. But you’re talking about, how do we create practices and communities that everybody sees — that are magnetic, that you want to run towards?

brown: Toni Cade Bambara said we have to make the “revolution irresistible.” And I think about that — she’s quoted, and there’s a whole essay from Alexis Pauline Gumbs in the book about her work. But I think about that, because I’m like, we need — and it’s all connected, to me, the radical imagination work, the emergent strategy work, the pleasure activism work. It all connects, because it’s like, we are trying to create a future in which we can actually survive. And we want to make it feel good, smell good, taste good; we want to make sure that everyone feels like they could belong in it; we want to make everyone feel like their needs could be met in there. And we know that we can’t get there through punishment.

And there’s a pleasure — and I promise it. I always love to promise it to people, because I’m just like, I know everyone can experience this. There’s a pleasure from being present, truly present, where you’re like, I’m with the people I want to be with. I’m doing what I want to do. It only comes from being really present. And capitalism has us socialized to think we constantly have to be looking elsewhere for it, so we’re running around, not satisfied, not satisfiable, no sense of what that would be like.

And in our justice movements, that’s not a good look, because if we have no idea what it feels like to be satisfied, we won’t know when we win. [laughs] So I’m always like, we need to be satisfiable. We need to know what that feels like. And one of the fastest ways to know what that feels like is to be satisfied in the body. Like, you know what an orgasm feels like, most of us do, and even if we can’t feel an orgasm, we can feel pleasure. We can feel the beauty —

Tippett: Ease, right?

brown: Ease of being present.

Tippett: That is actually not so accessible to so many of us, just that. Yes, there’s the — there’s capitalism that is constantly making us not present, and there’s also a world of fear, right?

brown: Totally.

Tippett: Again, kind of circling back, it is a time of unstoppable change, and change is so unsettling. And different kinds of people are on the losing end of this change, or fear that they are. And fear has — right? Fear has also — fear is the greatest example of the power of imagination because even a perceived threat…

brown: That’s right; mostly it’s imagined. [laughs]

Tippett: … lands with the power of threat. I appreciate a piece that you wrote — I think this was on your blog — “a word for white people, in two parts.” And you talked about — first of all, you speak as a mixed-race Black woman; that you think about your — you understand that you are connected to lineages of harm, even as you are harmed by these lineages in your body.

And you — I appreciate this sentence so much, which is just humanizing this: “supremacy is our ongoing pandemic. it partners with every other sickness to tear us from life, or from lives worth living.” To me that kind of — you’re saying, let’s move towards lives worth living. I really love that.

brown: Lives worth living.

Tippett: At the beginning of that blog post, you put, “a word for white people in two parts” — “part one: what a time to be alive,” which is true and which is another way to frame it, right? And I feel like we should almost put that sentence at the beginning of so many of our conversations: what a time to be alive; that we are in this total paradigm shift, right? And that we are tasked with standing before these existential, potentially transformative junctures for our species.

brown: I mean, this is, to me, the most exciting thing right now, is like, we are aware, if we wake up, we are in a place where we can create so much history and so much change. Everything is falling apart, but also, new things are possible. And Octavia said that “[t]here’s nothing new / under the sun, / but there are new suns.” We are in a time of new suns. We’re in a time of new suns. We have no idea what we could be, but everything that we have been is falling apart. So it’s time to change. And we can be mindful about that. That’s exciting.

Tippett: Yeah. It’s buckle your seatbelt exciting, right? [laughs]

brown: Yes, it’s like — we are the action heroes. I always say that for organizers, but I’m like, really, to be a human, once you wake up and recognize, Oh, I can shape everything. I don’t have to be a victim of someone else’s vision for my subjugation, I actually get to be a powerhouse in the story of my own life and my people’s lives — oh! That’s a different invitation. I’d much rather live in that scenario. And so I do. [laughs]

Tippett: And you do it as part of an ecosystem, not as a bold individual, so that on the days that you can’t carry that, on the days that it’s not hope that you feel, but despair or exhaustion, you’re not standing there alone with those.

brown: Well, and I’ve been thinking about this a lot. A friend of mine, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, who I mentioned, I think, already — she’s such an incredible poet and incredible writer — but she also has been teaching me a lot, lately, about how just the idea of being an individual, that is a ridiculous idea. [laughs] She’s like, that’s a mythology. We’re not individuals. And the more I think about the ecosystems and emergent strategy and what nature is trying to teach us, the more I hear: we are one. When I think back to the first thing I felt like I understood, it was that. It’s like, oh, we are one.

Whenever I have a spiritual awakening, all of it resonates with that same song: we are one. We are one. We are one. And I think that’s what we’re supposed to be figuring out, is, so then, if we are one, how do we do that? How do we be one interconnected, living organism? How do we do that? And I think that’s our big human question for this time, and I think it’s a really good one to spend life on.

Tippett: So if you look around, if you think about this generative landscape, this emergent world that you’re part of and that you are speaking to and where there are conversations happening that social media can’t imagine. [laughs] I’ve seen you talk about “unthinkable thoughts” and favorite questions, and I feel like you are constantly — there’s always fresh thought that’s emerging in you, but I also see that it is — it’s coming out of presence, not just to what’s going on inside your head, but to what you see happening around you, what you’re part of, and also, always, other teachers. I’m curious — sometimes I ask people, at the end of an interview, about what is making you despair and what is giving you hope, right now, today. And I feel like, for you, the question is, what is your unthinkable thought? And what is your favorite generative question today? [laughter]

brown: Well, my unthinkable thought, lately, has been, will I be okay if humans don’t continue? For such a long time I’ve been really driven by the idea that we have to continue — we simply must, we’re so miraculous and incredible. [laughs] But lately, yeah, my unthinkable thought has been: but we might not. So far, we’re not making the kind of decisions that would lead to continuation, and what does that mean? And how do I still live a really meaningful life and fight utill the end? — because I do feel like that — I’m like, it is miraculous enough that I want to give it my whole life effort, but also, can I also be at peace with what is, which might be that we’re not willing to change? So that’s the unthinkable thought, and it’s unthinkable because it’s so — it really brings up so much grief for me. I really love life.

And then the question, which is actually from one of my teachers, Grace Lee Boggs, that she would always ask when we showed up to sit down and talk with her, is, What time is it on the clock of the world? And I like this question; it always makes me kind of deconstruct time, [laughs] when I’m like, Oh, we’re in these looping patterns, actually. And we’re in a pattern that feels familiar in these ways and new in these other ways.

So we’re in this interesting moment in Black movement where we came through this first, massive wave of Black Lives Matter and lots of Black organizing happening, and there’s a moment happening now that’s really tense and intense, and it feels like a lot of internal tension coming out into the light. But for me, this is also a moment of deep learning. And what we’ve never had before are the tools of communication and mediation, and there’s just so many people who are calling each other and being like, I don’t want to see us struggle in this way.

Tippett: So the tension feels like a time loop…

brown: The tension feels super time loop…

Tippett: …is not new.

brown: …it’s super familiar. Every time any movement — so it’s not just true for Black movement, but any movement that starts to get national acclaim and attention, there’s going to then be that backlash that happens within, of like, well who are you to — who are you?

Tippett: And also, the growing pains within the human drama, the growing pains of something that grows.

brown: Totally. That’s the loop, right? But then the different tools that we have this time around, first of all, is so many more people are paying attention to Black movement, period. And I think the vast majority of them are not getting caught up in that sort of movement internal stuff; I think the vast majority are just like, Okay, Black lives matter, [laughs] so I need to orient around that. And I think there’s so much beautiful work coming out of the Movement for Black Lives and Southerners on New Ground and the Catalyst Project and SURJ for white folks and allies. It’s just a different time of talking about racial justice and thinking about racial justice that is full of complexity. There’s so many people asking the questions of, what does Blackness even mean, can we interrogate this in a new way, and how do we keep it intersectional, how do we bring in all aspects of ourselves?

So I’m finding it a very exciting time, but it’s also a fraught time. And we’re able to look at it historically, more. When I talked — I got to be in a conversation with Angela Davis; she was like, yeah, we dealt with a lot of the same stuff, but now y’all know how to take care of each other and take care of yourselves. And now there’s therapy. [laughs] I have so many people who are movement folks who are like, I don’t know where you’d be if you didn’t have therapy. But with therapy you can be like, Oh, I don’t need to take all this personally. So there’s just more tools.

Tippett: You mentioned Grace Lee Boggs, and I’m so glad that I sat with her in Detroit in her last years, and also just sat with that community around her. You quote her on this matter of transformative justice and transformation; what is it that she says?

brown: “We must transform ourselves to transform the world.”

Tippett: I feel like that is something that this generation in time, and your generation and the ones coming after, know. And that is new. That is a new thing to internalize. Maybe that’s kind of what Angela Davis was talking about, too.

brown: I feel like there is this sense of, it’s not either/or. It’s just that you are a personal frontline. What’s happening in your life and in the relationships you have with your family and how you treat people when you’re upset with them — I always ask people that, when I talk about transformative justice; are you punishing anyone right now? And could that punishment be shifted into a boundary or a request? Is there a courageous conversation that needs to be had? How do you personally begin to practice whatever’s in alignment with your largest vision? Abolition is something we practice every day, in our lives. Liberation, emergent strategy, all of these are things to practice every day.

And I guess maybe to bring it back to the first question, of spiritual practice, to me that’s the ultimate spiritual practice, as well. It’s not about the bombastic meditation retreat. It’s about, can you sit every day? Can you bring mindfulness into every activity?

Tippett: Which also brings us back to fractals.

brown: Yes. [laughs] Isn’t it beautiful? Isn’t it absolutely beautiful?

Tippett: Yeah, I mean, you’re really I keep using this language of, how we really internalize in our bodies that this is what it’s about, that what you do, what you practice in your everyday, is a pattern that is part of that larger pattern that you want to see.

brown: That’s right. And there’s so much awakening, so I always tell people that you’re always practicing things. So it’s not like you go from not practicing to practicing; but it’s, Are you practicing things on purpose? Are you practicing things you would want to practice, or are you practicing what someone else has told you [laughs] is the right way to do stuff? And once you start practicing on purpose, then you can actually practice liberation and justice and freedom and — then I think you begin to have this contentment that comes from practice. Like I know that I won’t see total liberation in my lifetime, but I also feel very satisfied with how I’m practicing liberation every single day and in every relationship.

Tippett: And moving towards life.

brown: And moving towards life, yeah. [laughs] Life moves towards life, you know. That’s the trick.

[music: “Eventide” by Gautam Srikishan]

Tippett: adrienne maree brown’s influential books include Emergent Strategy, We Will Not Cancel Us and Pleasure Activism. More recently, she’s the author of Maroons, a work of speculative fiction and she co-edited the anthology Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction from Social Justice Movements. She co-hosts the podcast, How to Survive the End of the World. And a special heads up, in late summer 2024, she is publishing a new book that I am so excited about — it’s phenomenal — called Loving Corrections.

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Eddie Gonzalez, Lucas Johnson, Zack Rose, Julie Siple, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Gautam Srikishan, Cameron Mussar, Kayla Edwards, Tiffany Champion, Andrea Prevost, and Carla Zanoni.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. We are located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. Our closing music was composed by Gautam Srikishan. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

Our funding partners include:

The Hearthland Foundation. Helping to build a more just, equitable and connected America—one creative act at a time.

The Fetzer Institute, supporting a movement of organizations that are applying spiritual solutions to society’s toughest problems. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, Dedicated to cultivating the connections between ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting initiatives and organizations that uphold sacred relationships with the living Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

And, the Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.