Eugene Peterson

Answering God

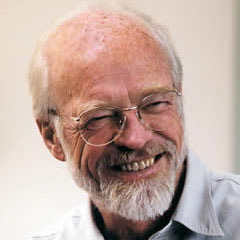

“Prayers are tools not for doing or getting, but for being and becoming.” These are words of the late legendary biblical interpreter and teacher Eugene Peterson. At the back of the church he pastored for nearly three decades, you’d be likely to find well-worn copies of books by Wallace Stegner or Denise Levertov. Frustrated with the unimaginative way he found his congregants treating their Bibles, he translated the whole thing himself and that translation has sold millions of copies around the world. Eugene Peterson’s literary biblical imagination formed generations of pastors, teachers, and readers. His down-to-earth faith hinged on a love of metaphor and a commitment to the Bible’s poetry as what keeps it alive to the world.

Image by Greg Fromholz, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Eugene Peterson wrote over 30 books including Answering God, Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places: A Conversation in Spiritual Theology, and The Message: The Bible in Contemporary Language. In 2021, a Lenten sermon series of his was published posthumously with the title: This Hallelujah Banquet: How the End of What We Were Reveals Who We Can Be. He served as the pastor of Christ Our King Presbyterian Church for 29 years. He spent the last years of his life with his wife, Jan, at the home his father built in Lakeside, Montana, just outside Glacier National Park. That’s where he was when he spoke with Krista in 2016, two years before he died at the age of 85.

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang

Krista Tippett, host: “Prayers are tools not for doing or getting, but for being and becoming.” These are words of the late, legendary biblical interpreter, teacher, and pastor Eugene Peterson. He authored dozens of books, like Answering God, about praying with the Psalms, and Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places, jumping off a line of Gerard Manley Hopkins. At the back of the church Eugene Peterson pastored for nearly three decades, you’d be likely to find well-worn copies of books by Wallace Stegner or Denise Levertov. Frustrated with the unimaginative way he found his congregants treating their Bibles, Eugene Peterson translated the whole thing himself, and that translation has sold millions of copies around the world. His down-to-earth faith hinged on a love of metaphor and a commitment to the Bible’s poetry as what keeps it alive to the world.

Eugene Peterson: All the prophets were poets. And if you don’t know that, you try to literalize everything and make a shambles out of it. A metaphor is a really remarkable kind of formation, because it both means what it says and what it doesn’t say, and so those two things come together, and it creates an imagination which is active. You’re not trying to figure things out, you’re trying to enter into what’s there.

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Eugene Peterson spent the last years of his life with his wife, Jan, at the home his father built in Lakeside, Montana, just outside Glacier National Park. And that’s where he was when we spoke in 2016, two years before he died at the age of 85.

I’d like to start by just asking you how you would start to describe the religious and spiritual background of your childhood.

Peterson: I grew up in a very sectarian church, a Pentecostal church. It was a small little church in the center of town. I guess what I would say is it was exciting. There was just a lot of stuff going on, and going to church was an adventure. And I don’t think it had anything to do with the gospel, but it was a good place to be, for a young person, teenager. So I had a positive relationship to the church. It wasn’t always — I had to outgrow a good bit of it, but it was easy to do. My parents were good parents, and faithful, and no hypocrisy in them. That’s really where — and I didn’t really get outside of that until I went to university.

Tippett: You’ve written — I think you wrote somewhere that the church you grew up in was less interested in this world than it was in spiritual matters.

Peterson: That’s true.

Tippett: But I sense that the — just the Montana landscape, for starters, kind of formed you — began to form you differently, your own spiritual imagination differently.

Peterson: Yeah, that’s true. We lived in the middle of this magnificent world, but we didn’t — my parents didn’t do much with it. But when I was a young person — well, young: seven, eight, nine, ten years old — I was within walking distance of a range of mountains, and every Saturday I used to boil a couple of eggs and get some bacon and ride my bike to the slope of these mountains. So I did have a — grew up with a sense of the beauty of this place and how unusual it was. But I did it pretty much on my own; as you just mentioned, my parents were a lot more interested in heaven than in Earth. But it didn’t seem to hurt any.

Tippett: I can’t find in your writing, and perhaps I’ve missed it, but where were the roots of your love of language, and the care you take with it, the reverence you have for its poetic possibilities? Where did that come in, for you?

Peterson: I think — I had a couple of teachers in high school, who loved language and who taught me how to write. And I think a lot of it was just kind of happenstance. I would find a poet, and I realized that I loved poets.

I can put my finger on one thing: we moved across town, when I was about — maybe 10 years old, and I had no friends. And I had a Bible that I’d purchased with my own money, and I started reading it, because I had no friends. And somebody told me that the Psalms were a good thing to read, so I started reading the Psalms.

And I couldn’t understand them. God is a rock? What does that mean? “My tears are in your bottle”? What is going on here? And I just kind of struggled with that, and — but people had told me it was important to read the Psalms. And about a month into that, I realized what they were. And I didn’t know the term “metaphor,” but I realized what metaphors were. And so then, so I was off, and the Psalms were my introduction to poetry.

Tippett: So, you became a pastor. It doesn’t sound like you were always destined for that; at one point early on, you thought you would be a professor. But you not only became a pastor, you became kind of a pastor’s pastor, and your writing has been so important to people’s formation, and in your most recent book, The Pastor, you write that you can’t imagine, now, not having become that.

But even that — the resonance of that word, in the world reading you now, as well as the world of church, is so radically shifted, changed. And so that’s kind of what I want to talk to you about. I want to kind of draw out your spiritual imagination and your scriptural imagination; and I want to kind of draw you out as a public theologian, because I think that all of that speaks to the world we inhabit today — even a world in which a lot of the context in which you grew up and in which you formulated your ideas and your writings is very different.

Peterson: Well, that’s true. I think I became a pastor when I was in graduate school, studying to be a professor. And I was going to be a Hebrew and Greek professor, basically. And then I got married, and I went — and then we moved to White Plains, and they didn’t pay me very much at the seminary. And so I had to have another job.

So I got a job with a pastor who I respected — I really had never had very high opinions of pastors, to tell you the truth. They’d come into our town and hunt and fish for a couple of years and then, go for a better place. You know, I liked them — they were fun, told good stories — but there was nothing about God that had any kind of connection with my life.

And then I was teaching, and the first course I taught was the Book of Revelation.

Tippett: Right. That’s a great place to start. [laughs]

Peterson: Well, it was. And I struggled through that, and then I started reading the Revelation in a totally new way. I had help from one professor — well, he wasn’t a professor. He was dead, actually. But he wrote a book on the Revelation, which just transformed my imagination when I realized that John was a poet. This was the first great poetry in the Christian faith. And when I realized that, then all that — well, the images, the symbols and everything — started to fit. And I quit trying to literalize them and began to see what was going on.

And then that — and here I was, in New York City and — Babylon. [laughs] And so I finally found myself living in a world which is outside the classroom, and there were divorces and suicides and runaway kids, and — it was just — I never knew what was going to happen on any day of the week, except Tuesday and Thursday, when I taught my classes. [laughs]

Tippett: [laughs] So what you said a minute ago, about the poetry — and you have actually also — you are a writer, but also a translator. The Message, your translation of the Bible, is revered by so many people — different kinds of people, from Bono, who recently interviewed you, to one of our producers, Lily, actually, who’s there, whose father was a pastor …

Peterson: Yeah, she told me.

Tippett: … and from Colombia and used The Message with his congregation of people whose first language was not English. But what you said a minute ago, about the poetry of the text, is — even in many of the translations many of us grew up with — not evident. And without that being evident, even sometimes in the way it was laid out on the page — and this is so clear in the way you write about this, the language — then without that context, we couldn’t — it wasn’t possible to read it …

Peterson: No, that’s true.

Tippett: … to understand it, to inhabit it.

Peterson: All the prophets were poets. And if you don’t know that, you try to literalize everything and make a shambles out of it.

Tippett: Talk about what difference that makes even to 21st century people, reading the prophets or having an imagination about prophets. What difference does it make, to know that they were poets?

Peterson: Well, it means you’ll learn what the meaning of metaphor is and that you — a metaphor is really a remarkable kind of formation, because it both means what it says and what it doesn’t say. And so those two things come together, and it creates an imagination which is active. You’re not trying to figure things out, you’re trying to enter into what’s there.

[music: “The Light” by The Album Leaf]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, a classic On Being conversation with the late, beloved pastor and literary theological writer Eugene Peterson. His translation of the Bible, titled The Message, has sold millions of copies around the world. To give a flavor, here’s how he rendered a well-known verse in the Gospel book of John. The King James Version reads: “And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us (and we beheld His glory, the glory as of the only Begotten of the Father), full of grace and truth.”

Eugene Peterson translates: “The Word became flesh and blood, and moved into the neighborhood. We saw the glory with our own eyes, the one-of-a-kind glory, like Father, like Son, Generous inside and out, true from start to finish.”

[music: “The Light” by The Album Leaf]

One thing you wrote about poetry is that — I’ll just read this. It’s wonderful language. “Poets tell us what our eyes, blurred with too much gawking, and our ears, dulled with too much chatter, miss around and within us. Poets use words to drag us into the depth of reality itself.” And I really like this — “Poetry grabs us by the jugular.” “Far from being cosmetic language, it is intestinal.” [laughs]

Peterson: [laughs] I wrote that?

Tippett: Yes, you did. [laughs]

Peterson: OK.

Tippett: I’m just — I’m pressing on this a bit because I think that really, maybe, even again, right now in our time, there’s an interest in the notion of prophets. But I’m also just — I think you have a way of talking about what prophets bring us, partly through the particularity of their language, that shakes us out of our usual categories of thinking and action.

Peterson: I think you’re right. I think it’s a — well, it’s been important for me; I would think it would be important for anybody, but to find a few poets that really strike home to you and then memorize them, and to learn to listen to the dynamics of their language and recognize things that — if you’re just looking at the words, for me, George Herbert has been one of those poets. Gerard Manley Hopkins. Mary Oliver. I don’t have a lot of them, but I memorize them, because then I can — their music gets inside my head, and I’m reading poetry without knowing I’m reading poetry.

And then that helps with the scriptures, too. I didn’t realize — when I did The Message, I had a congregation of people that didn’t read books. And so I started translating the Bible in their language, not knowing what I was doing, and suddenly, they started paying attention to me in a way they never did before. And so I think — and see, I didn’t call it poetry. If I’d have done that, they would have quit. I think people who use language have to be pretty subversive. I don’t know if you want to cross this out or not, but we’ve got a huge, huge thing going on in our country now, which is — despises language.

Tippett: Actually though, what I see — that there’s a lot of — the worst of what’s happening in the political sphere right now, though, is kind of an extreme version of the way we’ve been so careless with language …

Peterson: Oh, it is.

Tippett: … in general. So there’s this line of yours, and I actually don’t know — can’t remember where this came from, but you wrote, “We cannot be too careful about the words we use; we start out using them, and they end up using us.”

Peterson: I think that’s true.

Tippett: I mean, I think that’s informed by your scriptural perspective, but it speaks very directly to [laughs] profane realities. I mean, say some more about how words — that power of words, and that power of words if we don’t use them carefully enough.

Peterson: Well, the power of words, when they’re used well, is multileveled. Most words have more than one meaning. And if you reduce words just to what you find in the newspaper, you have missed out on a whole chunk of human living. And this is where a poet helps us: he trains our minds to hear stuff we didn’t hear before. And that’s what’s quite wonderful about having children; they sometimes use language in a kind of — they discover words, and they start using them in ways we never thought of doing. And I think children in their pre-school days have a lot to teach us about language.

Tippett: It’s true, also, that as we watch our children acquire and master words, that power of words is very evident.

Peterson: Yeah, it is.

Tippett: Something you said about prayer also strikes me as — so it strikes me that when you talk about the power of words, the importance and care with them, it’s not just speaking. It’s also about reading; it’s also about listening. You talk about if we pray without listening, we pray out of context. It seems to me the same thing kind of comes through about speaking: if we speak without listening, we speak out of context. And listening also doesn’t accompany a lot of our public speech now.

Peterson: I think the listening business is the part of prayer that gets most neglected. And plenty of people have taught me this, but one of the best teachers, for me, has been Karl Barth. And he’s just adamant about, when you pray, you don’t ask God for things. You pray to listen. And then, when you’ve listened, you can hear God speak and take you into paths you’d never thought about.

Tippett: You propose quite a different relationship. I mean, you say, “God speaks to us; our answers are our prayers.”

Peterson: Does that not make sense?

Tippett: No, it does. It’s just a — it’s a whole different way to — entry point to thinking about what’s happening in prayer; to even, I think, a Protestant, Western Protestant approach that’s been there in many churches for a while.

Peterson: And that’s one of the things that I think I liked about being a pastor is the working through in conversations of this kind of reversal of what they’re used to doing. And the ability to make the transfer from asking to listening is really profound, but when you start to do it — and it sometimes takes some coaching, some encouragement from a pastor or somebody else — but it’s so freeing.

I remember a conversation I had when I was a pastor. I went to see a woman who was lonely. And she was — she had a — I don’t know what they call them; a hoop that you spread paper or cloth over and you’re doing, working in it. And what do they call those?

Tippett: Needlepoint, or something like that?

Peterson: Needlepoint, but there’s a word for that thing you’re holding. Anyway, she said to me, “My life is just limp. I just need something to give me some definition.” And she said, “Like this thing I have, you can stretch it out tight, and everything starts to fit.”

And so I told her, “Let me get you one of those.” And so I came back in a couple days with a copy of the Psalms, and I said, “This is it. This is what you need. You just take one of these psalms, and just let your mind stretch around it, and see what happens. Don’t try to read a lot of psalms, just take one, two, three, whatever.”

And it’s amazing, what that does.

[music: “K&F Thema (Pizzicato)” by Apparat]

Tippett: In the New Revised Version of the Bible that many of us read in church, Psalm 22, a cry of anguish from King David, begins: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? Why are you so far from helping me, from the words of my groaning?”

In Eugene Peterson’s translation, The Message, he writes:

“God, God . . . my God!

Why did you dump me

miles from nowhere?

Doubled up with pain, I call to God

all the day long. No answer. Nothing.

I keep at it all night, tossing and turning.”

[music: “K&F Thema (Pizzicato)” by Apparat]

After a short break, more with Eugene Peterson.

[music: “K&F Thema (Pizzicato)” by Apparat]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, for the season of Easter, my conversation with the late, legendary pastor and theological writer Eugene Peterson. His literary biblical imagination formed generations of pastors, teachers, and readers. We spoke in 2016.

You say that the Psalms train us in the conversation with God that is prayer. What is your practice of — I mean, so there is this traditional practice in Christianity of praying the Psalms, just praying through the Psalms, and it’s what the monastics do. Do you have that kind of — have you had that kind of practice in your life? Or how do you work with the Psalms in your personal spiritual life?

Peterson: Oh, it’s hard to talk about …

Tippett: I get that. I get that.

Peterson: … because there’s so much goes into it. But for years I have — the first thing in the morning, I have about an hour of just quiet and coffee. And — but I picked seven psalms that I thought were — kind of covered the waterfront of what’s going on. And I memorized them. And I picked pretty long psalms, so I’d have to work at it. And so on Sunday, I do Psalm 92, which is a Psalm for the Sabbath. And then I go to Psalm 68, which is kind of a — it’s a collection of pieces of psalm, from different kind of settings, but when you read through the whole thing — it’s a pretty long psalm — you realize all of these things kind of fit together, if you’re paying attention.

Tippett: When you say “all these things,” do you mean all the different moves — all the different moves that a psalm makes, from praise to fury to desolation? Is that what you mean?

Peterson: Right, right. They’re not logically connected. But with an imagination, they start to fit together. That’s what I mean.

And then Psalm 18 is a psalm just full of metaphor, and just — you’re just overwhelmed by all the ways in which you can reimagine God working in your life. And just, I do seven of those. But I’ve been doing that for years.

So then — [laughs] you want to know the whole story? Then I shut up. And I just breathe deeply and, for another 15, 20, 25 minutes, just try to empty myself of everything. But there’s enough going on, through that first entry, that it seeps into your imagination, and so you’re not really just emptying yourself; you’re emptying yourself of a certain amount of clutter so that the words you really need to know kind of fit in.

I don’t think it’s a very good idea to give people a pattern to work with, in prayer. We’re all a little bit different. And I did that myself; I just figured out what seemed possible to do, and I did it. But when I was a pastor, I would spend time with people, figuring out what to do.

Tippett: Helping them …

Peterson: Helping them to —

Tippett: … find their whatever their seven psalms might be, or the equivalent.

Peterson: That’s right.

Tippett: You know, one of the words that’s important to you is “honesty,” that the Psalms train us in “honest prayer” — “immerse us,” as you say, “in the stream of life as it is, wet and wild.” And I think your books — maybe especially Answering God, but not just Answering God — have been part of the training of seminarians and theologians for a few generations here. And I think one of the things you talk about is that the honesty of the Psalms — that bringing every possible human, everything human, before God, which even lectionaries — I mean, even official Christian texts have often shied away from or edited out the cursing, the imprecatory psalms. The beautiful psalm that we all know, we can sing — “By the waters of Babylon, there we sat down and wept” — but that also has a moment where it says, “Happy shall be he who takes your little ones and dashes them against the rocks.”

Peterson: That’s right.

Tippett: But for you, that honesty about the human condition is absolutely at the heart of what is necessary about the Psalms.

Peterson: Yeah. It is; and how else do you get permission to do that, except you have something that’s in the Bible; it’s inspired, it’s been practiced, dealt with by people for thousands of years?

I was in conversation with Bono, just two months ago, and he was talking about — we were talking about the Psalms, and he says, Well, what do you do when you get angry? I’m not quoting. And I said, Well, you’ve got to learn how to cuss without cussing. And I think that’s what the psalm — like “the waters of Babylon, where we sat down and wept” — there are ways in which you can express your anger, in a context which doesn’t become mean. And I think that’s what the Psalms have always done — not just the Psalms, but the stories.

Tippett: Yeah, the Biblical stories.

I know that you will be aware of this, too, that at this particular moment in history, there is some sense that these kinds of passages and imagery in the Bible are part of what is dangerous about the Bible in the world. I think you — here’s something you say. I think you have a more sophisticated way of talking about what’s going on, and what it is meant to work in us. I mean, you wrote, “It’s easy to be honest before God with our hallelujahs … somewhat more difficult with our hurts … nearly impossible to be honest before God in the dark emotions of our hates.” Talk about what is redemptive and actually good for the world, in people being able to bring the dark emotions of their hates before God.

Peterson: Well, I think people need to be given permission to do it, to find a language of hate, disappointment, retaliation, and get that out. People who repress all those emotions often get sick, depressed. Learning how to express our fears, our discomfort, our hate, if you will, it’s often very freeing.

Tippett: So is it your sense that if people can bring that before God, it’s less dangerous, as something that’s in the world?

Peterson: Oh yes. Oh, much less.

Tippett: And that’s just kind of one of the mysterious things about [laughs] human beings in the world, isn’t it? The mystery of us.

Peterson: It is, yeah. And I think that’s where art comes in, too. The artist can sometimes bring out these feelings, perceptions, that we don’t know how to do it ourselves. And yet if they’re a good artist, they know what they’re doing, and they’re honest, they can be of great help.

Tippett: You wrote in The Pastor, your new memoir, I think you spoke to the phenomenon I’m talking about, which — we’re talking about how the Psalms of the Hebrew Bible bring every human aspect into the light, even the worst. And so that is a way of — you talk about crowds. And you said, “Classically, there are three ways in which humans try to find transcendence … through the ecstasy of alcohol and drugs” — chemically induced transcendence — and “recreational sex, and through the ecstasy of crowds.” And you said, “Church leaders frequently warn against the drugs and the sex, but, at least in America, almost never against the crowds.” And there’s something about the moment we inhabit, I think even globally, that that feels very resonant and psychologically astute.

Peterson: Well, I think it’s true. But the poets and the writers that use writing as a way of conveying truth, rather than just entertaining people — I used to, when I was a pastor, I used to get a pile of books, the same book, like 10 or 20, 30 books, and buy them and put them in the narthex and ask people to pick it up and read it. There are some really great Christian writers, who really keep you burrowed into the reality of your life; the world’s life.

Tippett: Who would be in that pile?

Peterson: Well, Charles Dickens is one. And I think I’ve read all his books three or four times.

Tippett: And most people would not think of Charles Dickens as Christian reading.

Peterson: That’s true, but he is. I mean, that’s Christian reading if there ever was one.

Tippett: Say some more.

Peterson: Well, he enters into the life of these poor people and bad people and stupid people and makes them come alive. And you — “I’m never going to do that,” you think; and then you do, and then you know you did it.

Wallace Stegner, I think, is one of our most healthy novelists. And my wife and I have — we often, in the evenings, we read a book aloud. And I guess we’ve read Stegner’s books aloud five or ten times.

Tippett: You know, again, I don’t know that people would think of that as a book that would be in the back of a church.

Peterson: [laughs] I know. I know.

Tippett: [laughs] This is a huge question, so I’m just going to ask you how you would start to answer it. What, at this stage in your life, what continues to perplex you? What do you not have answers for that you would like to have more answers for? What has surprised you, even as you’ve moved through anger and forgiveness and sadness and the things that go wrong in a human life?

Peterson: Well, you know, I don’t — I’m 83 years old now. And one of the things that’s surprised me is the lack of questions I have now. It’s kind of like I’ve just entered into a world where everything is going — not the way I thought it would go, but the way it makes sense. I forget things a lot, I misplace things, and I used to get angry with myself. And I don’t anymore. This is a way a lot of the world is living, is to — [laughs] is to just enjoy it. So you’ve got to go look for your keys for half a dozen times before you find them?

And having a family helps. I’ve got three children and nine grandchildren. That puts you in a context where there’s a lot to be appreciated and a lot to worry about. And the worries don’t crowd out the glories, but we’ve got to give ourselves permission to do that.

[music: “Prelude for Time Feelers” by Eluvium]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, a classic On Being conversation with the late, beloved pastor and literary theological writer Eugene Peterson. Here are some lines from his memoir, The Pastor:

“My work has to do with God and souls — immense mysteries that no one has ever seen at any time. But I carry out this work in conditions — place and time. … Place. But not just any place, not just a location marked on a road map, but on a topo, a topographic map — with named mountains and rivers, identified wildflowers and forests, elevation above sea level and annual rainfall. I do all my work on this ground. I do not levitate. …

Time. But not just time in general, abstracted to a geometric grid on a calendar or numbers on a clock face, but what the Greeks named kairos, pregnancy time, being present to the Presence. I never know what is coming next.”

[music: “Prelude for Time Feelers” by Eluvium]

Once, you wrote, “People ask, ‘How do you mature a spiritual life?’” And you said, “The one thing you do is you eliminate the word ‘spiritual.’ It’s your life that’s being matured, it’s not part of your life.” [laughs]

But the word “spiritual,” much more than when you first became a pastor, is everywhere now. And I want to know how you hear that, respond to it — what you think of it.

Peterson: I think it’s cheap. You’re taking something, putting a name on it, “spiritual,” which means it’s defined. The whole world is spiritual, and the word “spirit” is “wind,” it’s “breath.” Well, people are breathing all over the place; they’re all spiritual beings, but if you have a name for it, you can compartmentalize it, and that just wreaks havoc with the whole thing. Spirituality is — and that’s why I don’t like the word, because it’s so easy to just say, “Well, he’s such a spiritual person. She’s such a spiritual person.” Well, nonsense. You are, too. And I guess that’s where I think the church has a place, which is maybe more important than it’s ever been. But it’s — done well, there’s no spirituality that you can define.

Tippett: Because it is in everything you do?

Peterson: That’s right. And if you don’t recognize that that’s possible, you just subtract a whole part of your life.

Tippett: You have always balanced what I’m going to inadequately call your spiritual life … [laughs]

Peterson: [laughs] OK.

Tippett: … with a very robust intellectual life — a love of ideas; a love of the rigor of the text and the teachings. Has that been something you felt you had to balance? Has it been a creative tension? And that also makes you different than the way a lot of people live with this part of their lives and, in fact, are equipped. People aren’t really given the tools to live with this part of their lives, with that rigor.

Peterson: Oh, I don’t know — I just always loved books. I always loved good books, loved writers. It’s not been — it hasn’t been an effort for me, hasn’t been a discipline. It’s been a — [laughs] it’s been a spirituality. [laughs]

Tippett: [laughs] There you go, contradicting yourself.

Peterson: [laughs]

Tippett: I wonder — you’re 83. I think, actually, this last exchange just kind of pointed out the complexity of dealing with words, even though they are so precious. And I just wonder if other words — if words themselves, even the word “God” — become too small, after 83 years of pondering and grappling with the immensity of the reality and who God might be.

Peterson: They do become too small.

Tippett: Does the word “God” feel too small to you, at this point?

Peterson: Yeah.

Tippett: What do you do about that?

Peterson: I pretty much am very circumspect about using it.

Tippett: What about the word “Christianity?” [laughs]

Peterson: Oh, that’s even worse. [laughs]

Tippett: Right. Well, just say a little bit about that.

Peterson: Well, the people who use the word “Christianity,” mostly, are thinking of an institution. And that’s hard to get rid of. Most of us have negative influences about the church; certain churches; experiences we’ve had. And so why don’t we just eliminate the word?

Tippett: But how —

Peterson: Of course, that’s hard for people like me, who is part of so-called Christianity.

Tippett: Exactly. I mean, your life and your writing is passionately interwoven with this enterprise, this aspiration, of church.

Peterson: That’s true.

We go to a small church. When I was a pastor of a congregation, people would leave and say, “How do I pick a church?” And my usual answer was, go to the closest church where you live, and the smallest. And if, after six months, it’s just not working, go to the next smallest. [laughs]

Tippett: [laughs] OK, so what is it about small, rather than big?

Peterson: Because you have to deal with people as they are. And you’ve got to learn how to love them when they’re not lovable.

And we go to a church now — I’m a Presbyterian, but it’s a Lutheran church. And most of the people are my age, and our pastor is young, and he’s a really good pastor, but I don’t go to church — I mean, I go there to be immersed in what I don’t know about. And these people — I mean, there’s 80 people in church, and I don’t — I know some of them quite well; I grew up with many of them. I would just — they still treat me like a little kid. And so that’s kind of refreshing.

Tippett: So you’ve written that “prayer matures into the practice of memory.”

Peterson: Yes, that’s true.

Tippett: It’s a wonderful sentence, “Prayer matures into the practice of memory.” And I wonder, just as my final question, has that been true for you? And what does that look like? How does that unfold? And how has your prayer changed, even as you pray the same psalms, year after year?

Peterson: Oh, I think the answer is easy. I think I’m praying when I don’t know I’m praying. It’s entered into my subconscious. And so I feel like — I don’t mean for this to sound “spiritual,” [laughs] but it is. It surprises me that something has been going on in me for years and years and years, which is pretty much absorbed into my psyche now. And it gives me hope. It gives me hope because our politics in this country are not very swift right now, and yet when I think about individuals I know, they’re not discouraged. They’re determined to do it right. And I feel like I’m a colleague with a lot of people who are my companions in this business. And you’re one of them.

Tippett: Thank you. Thank you so much for all that you’ve done and for having this conversation with me.

Peterson: So this is it?

Tippett: I think this is it.

Peterson: [laughs] It’s been a pleasure.

Tippett: Thank you.

[music: “Snowdonia” by Message to Bears]

Tippett: Eugene Peterson wrote over 30 books, including Answering God and The Message: The Bible in Contemporary Language. In 2021, a Lenten sermon series of his was published posthumously, with the title This Hallelujah Banquet: How the End of What We Were Reveals Who We Can Be.

Eugene Peterson died in 2018, at age 85. His son, Eric, who is a pastor near Spokane, Washington, wrote to us of his father, “He remained gentle and humble right up until the end of his long life and was simply the holiest man I’ve ever known. In death no less than life, he is a person of grace and truth.”

[music: “Snowdonia” by Message to Bears]

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org;

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org;

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives;

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.