Hanif Abdurraqib

Moments of Shared Witnessing

Hanif Abdurraqib’s writing is filled with lyricism, rhythm, people and precision. In his essays and poetry, he introduces readers to a soundscape of Black performance and Black joy: we hear hip-hop and jazz, we hear Nina Simone, Aretha Franklin and Little Richard. Music and performance of every kind are the source of his fascination, focus and wisdom: what makes people cry, or feel safe, or brave; held in struggle, joy, or love. Hanif is interviewed by our colleague, Pádraig Ó Tuama, a poet himself and the host of On Being Studios’ Poetry Unbound podcast, now in its third season.

Image by Kate Sweeney, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

Hanif Abdurraqib is a poet, essayist, and cultural critic from Columbus, Ohio. His poetry has been published in Muzzle, Vinyl, PEN American, and various other journals. His essays and music criticism have been published in The FADER, Pitchfork, The New Yorker, and The New York Times. His books include A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance, The Crown Ain’t Worth Much, They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, and A Fortune for Your Disaster. He’s also the host of the podcast, Object of Sound.

Pádraig Ó Tuama is a theologian, writer, and conflict transformation practitioner. He is a member and former leader of the Corrymeela Community of Northern Ireland. His books include an incandescent memoir, In the Shelter: Finding a Home in the World; a prayer book, Daily Prayer with the Corrymeela Community; a book of poetry, Sorry For Your Troubles; and a book of theology and politics co-authored with Glenn Jordan, Borders & Belonging. He hosts the On Being Studios podcast Poetry Unbound. His forthcoming book, Poetry Unbound: 50 Poems to Open Your World, will be published in October 2022 and is available for pre-order wherever you get your books. Pádraig grew up in the Republic of Ireland, near Cork.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: Hanif Abdurraqib is a cultural critic and poet. Music and performance of every kind is everywhere for him — what makes people cry or feel safe or brave, held in struggle or joy or love. And I get to be a listener this week as my colleague, Pádraig Ó Tuama, a poet himself and the host of On Being’s Poetry Unbound podcast, draws out Hanif, whose work he loves. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Pádraig Ó Tuama, guest host: Hanif Abdurraqib’s writing is filled with lyricism, rhythm, people, and precision. In his essays and poetry, he introduces readers to a soundscape. We hear hip-hop and jazz. We hear names like Nina Simone, Aretha Franklin, and Little Richard. He’s interested in Black performance and Black joy, and what that feels like in auditoriums and audiences, in sport and television, public and private.

Hanif Abdurraqib: I’m such an audience watcher because, be it for films or for concerts, I really love seeing how people are impacted and affected through a moment of shared witnessing. And that compels me and brings me closer to what feels like a type of emotional salvation.

Ó Tuama: Hanif’s mother died when he was barely a teenager, and he wraps this grief in with grief and objection at societal inequities and racism, to write with profound wisdom about what contributes to safe and meaningful expressions of joy, grief and everything in between. Hanif Abdurraqib was born and raised in Columbus, Ohio, where he still lives. His latest book is called A Little Devil in America: Notes In Praise Of Black Performance. You can also hear him talking passionately about all things music on his podcast, Object of Sound.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

So, Hanif, I am thrilled to talk to you, and a question I’d like to ask you is to tell us your earliest memory of music.

Abdurraqib: The first song I remember hearing, or the first song I have a vivid memory of is, weirdly, a song that gave me a nightmare when I was kid. And I don’t remember my dreams much and never have, but I remember this so vividly that the details of the nightmare still stick with me. And that song was Nina Simone’s version of “Pirate Jenny,” from her 1964 concert album. And of course, “Pirate Jenny” is a song that first got its notoriety in The Threepenny Opera. But Nina Simone, as gifted as she was at many things, was perhaps most gifted at taking songs that were perhaps not constructed with Black people or Black experience in mind and molding them to haunt the edges of Blackness, be it for good or for bad.

And so — this definitely isn’t the first song I heard, but it is the first song — I was raised Muslim, and so that means that when I was born, my father sung the call to prayer in my ear, my right ear. So that was the first song I heard. But the first song I remember is Nina Simone’s “Pirate Jenny” because her rendition of it — you know, with what little I knew about the horrors of slavery, I could easily map onto her singing of that song where I thought, “The song is about a woman getting revenge on a town that has ridiculed her, and a boat rolls into the town, and it flattens the town, and then the woman rides off with pirates.” But through the lens of Nina Simone, it was easy to see how that could be transformed into a slightly more horrific narrative, but powerful narrative, about slavery. That gave me a nightmare when I was a kid, and I still remember the details of that nightmare to this day, and yet it is a nightmare I’m grateful for, because I think it speaks to the power of Nina Simone’s rearticulation of existing song.

Ó Tuama: Listening seems to be something that I hear over and over again, for you; like even the word “audience,” that comes from the Latin word meaning “to listen.” So does “audit.” And there’s power and there’s politics in the question of audience, but then there’s also self-care and self-reflection and self-challenge in the experience of listening to yourself. You uncover so many multiples of the experience of listening, and look at the experience of listening in public, in private, in safe ways as well as in ways that don’t feel safe and that are not safe. You do that over and over again, throughout your prose and your writing. What is it about listening as an act, and listening as an artistic act, as well as listening as a public, political act, that is of such interest to you?

Abdurraqib: Well, I think it’s because I grew up listening in somewhat joyful but isolated ways. I’m the youngest of four, and I grew up in a house that was teeming with music and varied music interests. And that meant that, for me, there was a lot of listening on headphones, because there was almost always music playing. I feel like when the house was at its fullest, you could hear music coming from the basement and from the third floor at the same time.

I think, because of the relationship I have with close listening, that informed the way I hear music — listening for things like inverted bass lines on Pet Sounds, the Beach Boys album, that kind of stuff — I’m listening for the trick, always. I’m always down to be fooled. And not in a large-scale way, obviously, but I love being fooled by an artist who is trying to pull one over, and I love catching them trying.

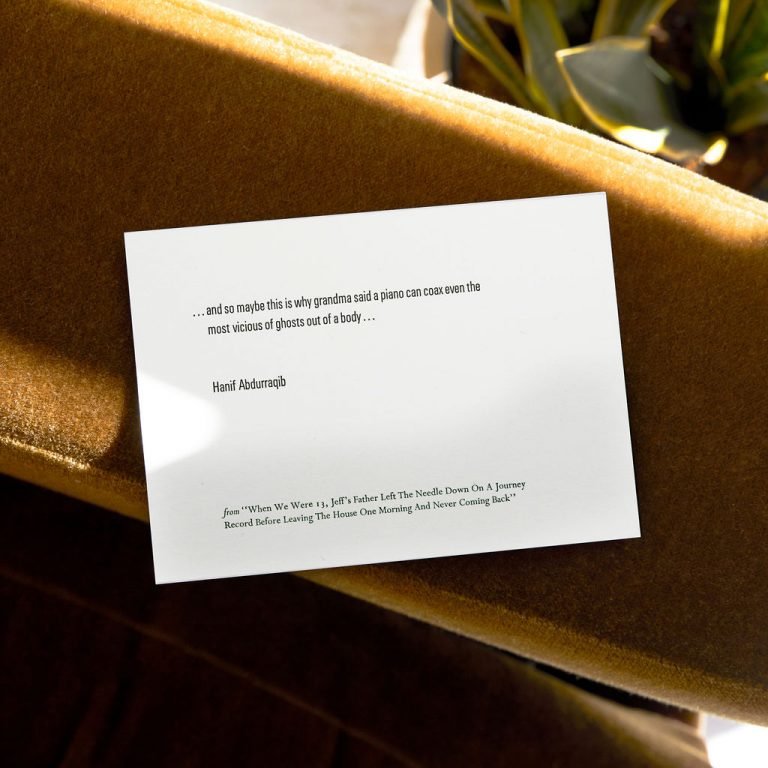

Ó Tuama: [laughs] You do that in some of your poems, too; like you’ve got some poems that are a whole setup, and then the final line or two will introduce this entirely new theme. In the poem “When We Were 13, Jeff’s Father” — it’s got such a long title. It’s a magnificent title. It’s describing Jeff’s father, who has left, and the soundtrack to this poem is “Don’t Stop Believin’,” by Journey, on their album Escape. And there’s so much about escaping happening in the poem. And then right at the end, we hear this moment of you being in a home, in a space that’s empty because of your mother’s death, and your father saying, “Play me something, child.” And that too feels like a trick, having hidden this experience of profound grief of your own childhood in an experience of observing grief and catharsis in your friend and your friend’s mother.

Abdurraqib: It’s interesting, because so much of what I do in my work, I think, is kind of masking larger concerns and lines of inquiry in popular culture, in the comforts of popular culture, in the comforts of what some people might consider to be familiar. And that is the case, I think, because I quite simply cannot, on my own, cope with the realities of what I’ve endured. I am doing that mostly for myself and not for anyone else, though I do think it works to serve people beyond myself. But I think that trying to be open and thoughtful and generous with myself and to be comfortable with everything I’ve worked through — I need that scaffolding. I need a gentler scaffolding.

Ó Tuama: Earlier on, you were saying that you were uncomfortable with the idea of speaking in plurals — saying “we all experience this” or “we know this” or “we know that.” You rather conjugate that to speak for yourself. But I often feel like you are asserting, in your essays on cultural criticism, that even the self, too, is a collection of individuals — that there’s a multiplicity and that there’s a desire never to be boxed by the way that somebody might want to say, “Because I know this about you, therefore I can assume this about you.” You seem to seek to move out from any of those categorizations and seek to assert that that isn’t a way to approach anybody, in performance or in personhood.

Abdurraqib: Yeah, I mean, because today I will be more than one person. The person I am right now, talking to you, is not the person I’m going to be later on, when I have a phone call scheduled to catch up with one of my old friends. That person is not gonna be the same person who drags myself to the kitchen to cook dinner even though I’m probably tired. And that won’t be the same person who kind of quietly plays video games in the darkness of my living room. All these things mean that I am almost required, I think, to not just speak for my “self” but to speak for the reality that I am someone who carries with me multiple selves. And to carry those multiple selves means that I have to again honor not just who I am in one moment, but honor the fluidity of moments to come, which for me means that I’m very comfortable with being incorrect. I’m very comfortable with crawling my way towards changing, and changing my ideas and feelings about something.

And there’s a real humility in that awareness, for me, because it is much easier to be egoless, for me, when I realize that I am multiple people stacked on top of each other, [laughs] and all of them have their own emotional landscape to tend to at any moment, from hour to hour, even. And that requires work that pulls me away from self-admiration in the mirror type of stuff, you know? To love oneself is hard work. But I think it becomes harder when you realize that you’re actually — at least, in my case — required to love multiple versions of yourself that show up without warning throughout a day, throughout a week, throughout a month, throughout a life.

Ó Tuama: I’d like to stay talking about this but maybe to expand the way that we’re talking about it, into your work in examining Black performance through your most recent book, A Little Devil in America, because you put the often singularities that are imposed upon performers, under a spotlight. And you — often, you put a particular spotlight on the audience expectation and the ways that audiences are yearning to be able to categorize a particular performer, and that the performer knows that they are multiple, but that the audience can sometimes resist that. Could you talk a little bit more about that and the way that you bring yourself to that in your cultural criticism?

Abdurraqib: So much of Little Devil’s project is uplifting stories and narratives of Black performance and Black performers in ways that they were not afforded by white audiences because of the sometimes narrow lens, the scope, of a white audience that feels interested and invested in distilling a Black performer down to their needs — the white audience’s needs — and that’s it. It’s like here in the States, when Stacey Abrams, among other organizers, did the work to flip Georgia to a Democratic state. All these white liberals were, to me, just dehumanizing Stacey Abrams, because they didn’t know how to engage — so often, these folks don’t know how to engage with a Black person doing something that pleases them. And so they’re just like, well, this person should be a superhero. This person should be — give them a Marvel movie. This person should have a cape. And it’s like, that’s a person you’re talking about, like a whole person.

But I think that’s very much aligned with — in A Little Devil in America, I talk about a couple instances of Black performers in the vaudeville era either dying onstage or passing out critically onstage and then later dying: Black Herman and Bert Williams. Both times that happened, the white audiences assumed that those collapses onstage were a part of an act. And so Bert Williams was onstage uncared for, for several minutes, while the audience applauded and whatnot. And it is perhaps too on the nose to say that that is a direct parallel in what I see when I witness white audiences reacting to Black performers — even Black labor — now, but I do think that it does hover around that. I mean, if anything, it’s a bit of an extended metaphor that has extended through decades and lifetimes. And this is a country that does not know how to, I think, adequately and effectively celebrate and uplift the fullness of a Black person’s living, unless they have died or been killed or done something extraordinary that serves empire.

[music: “Wholy Holy” by Aretha Franklin]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett. Today on On Being, poet and cultural critic Hanif Abdurraqib interviewed by poet Pádraig Ó Tuama.

[music: “Wholy Holy” by Aretha Franklin]

Ó Tuama: There is a quote that I wanted to bring you out about because I found it so moving. You’re speaking about Aretha Franklin singing in the “Amazing Grace” recording that then later on got turned into a movie, and talking about the way that the experience between singer and listener in a church is being created into this collaborative experience of joy and weeping and explosion of emotion.

Abdurraqib: Yeah, gosh, I’ve watched Amazing Grace like, so many times — so, so many times. I watched it twice during the pandemic, you know? And I’m not someone who — I didn’t grow up in the church; I don’t really have a relationship with the church except for through music, through sound, through a kind of relationship with how music can live in the spirit, in the soul. And gosh, Amazing Grace feels so important to me because of that. And to spend some time with what it means to get to the heart of a kind of seeking a higher power through sound — that feels important, to me. So I love Amazing Grace a great deal.

Ó Tuama: You watched the audience in this and watched that kind of extraordinary interplay between performer and audience in that film. But then you also turn your attention to the audience watching this in a theater. And talking about people turning up and watching this and having experiences with each other, you describe turning around and seeing people with handkerchiefs to their faces and not remembering when you started to cry, during one of the times that you saw it in theater, but knowing that you too were brought into an experience of audience that was transformative in a way that audience is uplifting, rather than the negative gaze of demand.

Abdurraqib: You know, I’m such an audience watcher because, be it for films or concerts, I really love seeing how people are impacted and affected through a moment of shared witnessing. And that compels me and brings me closer to what feels like a type of emotional salvation. Some of it is because I think I just am prone to feeling very big feelings all the time, and it’s somewhat comforting to look around and realize I’m not by myself in that, in this pursuit of feeling first and processing second. It feels really great to realize that I am not alone, as someone who’s maybe chasing that idea. And so I am a bit of an audience watcher, because I do think a part of that process brings me closer to feeling the kind of comfort that I almost need to feel in order to kind of get to, and through, the well of emotion that I am often immersed in anyway, and emerge from that well with something that is useful for me, going forward in the world.

Ó Tuama: You draw a distinction between audiences that are capable of supporting a person who’s showing out — you make a distinction between showing off and showing out. And you tell, over and over again in this beautiful book, you tell the stories about how, when people are showing out, that there is a community experience between the stage and the audience. And something bigger than anybody could’ve created individually happens in that space. How would you describe your ways of entering into the idea of showing out?

Abdurraqib: Part of me wonders now, because I’ve been asked this a lot, and part of me wonders if showing out is something one isn’t even aware of that they’re doing. It’s done without intention, is the thing. Showing off is done with intention, certainly. But showing out, perhaps, is just a person in the zone, not even aware that they’re doing what they’re doing, but still rendering an audience immovable with awe — and a specific audience, of people who know what they’re watching, of people who know what to look for. It’s like Steph Curry shooting a three and then nonchalantly turning to run back down court before the three even goes in, you know? That’s a small, intentional movement, but it’s also someone saying, I am so present and in the zone, I don’t even need to watch the outcome of this.

Ó Tuama: Yeah. Watching a person in glory.

Abdurraqib: Yeah. I think glory is the thing, right? That’s it, where — and I don’t want to say that showing off is bad either, because Little Richard showed off all the time, and that was exquisite, right?

Ó Tuama: [laughs] Yeah.

Abdurraqib: Little Richard is — to show off with intention is also an art form. And so I look at someone like Little Richard, and he could show off like no one else. And when you do it well — when you do it well, it really means something.

Ó Tuama: Friends of mine were part of a jazz band, and I used to go along and watch them. And I’d see the way the bass player and the electric guitar player and the saxophonist would sometimes do a riff and then hear how the other would echo it a little bit later.

Abdurraqib: Yeah, they’re showing out, right.

Ó Tuama: Yeah, but they had an enjoyment — you could see that they were looking at each other, going, “That was great.” And their enjoyment with each other, on a stage in a small bar, was so infectious to the audience, to be brought into a conversation.

Abdurraqib: Yeah, yeah. You know what? Jazz is like, really the art form where showing out happens, because it can be a form without language, like a language-less form. And so it relies on an audience’s understanding of what they’re witnessing, and it relies on maybe a small nod or a wink or a gesture that a player might do when they’ve hit a good groove. It relies on, again, being able to see the trick unfold. It’s how you get “awopbopaloobop alopbamboom,” right? There’s an ecstasy beyond language. Language is a faulty container for that level of ecstasy. And so that level of showing off is almost done for the creator, or the artist immersed in the sound, and not necessarily for the audience.

Ó Tuama: You know, when I’ve thought about poets engaging with the question of music, often I hear poets engage with the lyric of a song or the title of a song, and they locate the power through the lyric, or even the politic of a song through its lyrics. But I hear you over and over again on your podcast, Object of Sound, I hear you highlight that there is something about performance that is the message. It isn’t just the lyric. The lyric is part of it, sure, but it’s part of a much greater whole — a symphony, like you said earlier on. And it goes deeper than language. It goes deeper than words, into a, perhaps, a language of the body, or a language — I mean, maybe of the soul; I don’t think I’ve heard you call it that, but something elemental.

Abdurraqib: You know, I didn’t study writing. I didn’t grow up studying writing, I didn’t go to college for writing, I don’t have an MFA — I have no, quote-unquote — no one can see me, I’m doing like, large scare quotes — “formal training” in writing. And so most of my relationship with language was just hearing how my people spoke, growing up, which for me was something that connected me to an emotional understanding of the world that, in a way, was detached from language entirely and attached more to sound and tone, again, and just the ways that Black folks in particular can say one thing, but underneath it, there’s something else.

You know, when working on Little Devil, I got so deep into Soul Train archives …

Ó Tuama: I know.

Abdurraqib: … watching old Soul Train episodes. And there’s this episode where Morris Day performs. And after he performs, him and Don Cornelius do the little interview, and you can tell that there’s some kind of tension between them, even though they’re complimenting each other. Don says, “It’s good to see you, Morris,” and he’s like, “Yeah, it’s good to see you, too” — that kind of thing. But the way that the words they’re saying doesn’t match the tone of what’s actually happening in their interaction is something I know so well, because the Black elders around me did it for so long, which is why it’s so easy for me — now we’re coming full circle, right — it’s so easy for me, in a poem, to understand that what I’m saying is actually not mirroring what I’m feeling, which is why I love a song where the music does not match what is being expressed.

Ó Tuama: You explore that too in Whitney Houston’s “I Wanna Dance With Somebody,” saying that, you know, you look to say that she wasn’t a great dancer, but you look at what that might mean. Rather than just a pop catchphrase, you look down below that to go, what might it mean to want to dance with someone?

Abdurraqib: Yeah, you know, where it’s like, I’m not a great dancer. And I feel like any dance partner I’ve had in my life has been a partner chosen out of a type of mercy, you know …

Ó Tuama: [laughs]

Abdurraqib: … or has done me a mercy. I’m not a bad dancer, but I’m not a great dancer. I know my limits. And therefore, I know — [laughs] I know my type of, my level of partnering, you know? But I do think that, away from — pulled away from the expectations of the world — and now I’m using dance in a broad term that is not just about physical movement — but to be pulled away from the expectations of the world means that you can dance a little more freely. To unlatch oneself, I think especially for Black folks, from the gaze of a country, here in the States, that was not built to love you in any real, tangible way, means that, I think, your dance can be a little more freeing, if you allow for it.

[music: “I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me)” by Whitney Houston]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett. Today on On Being, poet and cultural critic Hanif Abdurraqib, interviewed by poet Pádraig Ó Tuama. The first episode of the new season of the Poetry Unbound podcast, which Pádraig hosts, features a poem by Hanif about childhood, friendship, and grief. It’s titled “When We Were 13, Jeff’s Father Left the Needle Down On A Journey Record Before Leaving The House One Morning And Never Coming Back.” You can hear that episode and listen to all of Poetry Unbound wherever you find your podcasts.

[music: “I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me)” by Whitney Houston]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today my colleague, the poet, theologian, and peacebuilder Pádraig Ó Tuama, is interviewing the poet and cultural critic Hanif Abdurraqib. Music and performance of every kind is the source of his fascination and his wisdom — what makes people cry or feel safe or brave, held in struggle or joy or love.

Ó Tuama: You again are turning the critical eye on the gaze. And you overheard somebody say, “How can Black people write about flowers at a time like this?” just after the 2016 election.

Abdurraqib: Yeah, at a Ross Gay reading.

Ó Tuama: [laughs] Oh, that’s right.

Abdurraqib: I was at a Ross Gay reading. Somebody said that [bleep]. I was like — oh sorry, I don’t know if I can curse on here.

Ó Tuama: No, that’s fine.

Abdurraqib: [laughs] I was like, yo, that’s wild. And you know, when that happened, I thought the easy thing for me to do would be to go home and write a poem about why that bothered me, why that person bothered me. But I think the more challenging thing was to strip it of this kind of individualistic impulse and ask myself, a person who does not know a lot about flowers — try to implicate myself in this investment that I have in the flower as a tool of articulating mortality and expectation around providing beauty despite a short life.

And that felt more interesting to me than being like, “Well, I went to this reading, and I heard this person say something, and I was mad about it” — which I was, obviously, but I didn’t want to give that person a space in the poem. The end, giving that person a space in the poem limited what the poem could be capable of, to me, when I wanted to do so much more.

Ó Tuama: Could you read the one that begins, “Forgive me”?

Abdurraqib: “How Can Black People Write About Flowers at a Time Like This”

“Forgive me, for I have been nurturing my well-worn

grudges against beauty. I am hoping my neighbors

will show some mercy on me for backing my car into

the garden & crushing what I will say were the peonies.

a flower with a short season. born dying. some might say

it’s a blessing to know your entrances & exits. forgive me, for

I have once again been recklessly made responsible

for the curation of softness & have instead returned with another

torrent of violence. in the brief moment of their flourish,

at the opening of spring, I drove across state lines to gather peonies for a woman

who loved me once. as a way of surrender, I pull the already

dying thing from the earth in a mess of tangled knots & I insist

that you must keep it alive for a year, even after it so desperately

wants to be done with the foolishness of its living. The last thing

I ask of this relationship is to burden you with another relationship.

it is so delicious to define the misery you are putting a body out of.

& just like that, we are talking about power. how awful this must be for you

I whispered as I closed my eyes & put the car into reverse.”

Ó Tuama: I was so struck by, just toward the end of that poem, where you say, “& just like that, we are talking about power.” And somehow, having the word “power” being highlighted so clearly in a poem, and in a poem with the word “flowers” in its title, I think of “flower power” and all the kind of imaginations that that brings from movies and a particular era of a certain population of America. And then what you’re doing here is talking about flowers and powers in terms of who says that who has the right to, A, speak in multiplicities, and B, speak about whatever they want to.

Abdurraqib: Right, yeah. Yeah, I’m glad you peeped that. And it’s like, for me, also the question of — you know, flowers don’t have much control over their living, or over what they offer to the world. And that’s true — I accidentally rolled over my neighbor’s peonies.

Ó Tuama: [laughs] It feels true. It’s so particular in the poem that when I read that, I thought, this isn’t a metaphor. This is fact.

Abdurraqib: Nah, I really rolled over the peonies. And I felt really guilty for it and still, to this day — I don’t live there anymore, but whenever it’s peony season, I buy some and drop them over — you know, I put them in their garden for them — because they were so kind about it when it happened. And I was like, yo, these are — I don’t know anything about flowers; I know peonies have a really short season, so I would not be as gracious as y’all are being, but thank you. And so I go back and put peonies in their garden every year because I still feel — my brain won’t allow me to not feel guilt for things for a very long time.

Ó Tuama: [laughs] Wow.

In The Crown Ain’t Worth Much there’s a way in which you speak about rhythm in the body and the inherited grief, not just the particular grief. And you live with both. Your mother’s death is such a powerful force in that book, and the continual return to exhaustion in the face of that particular grief, and attention as a teenager to that particular grief. And then there’s a broadening out, too, about what it means to inherit an experience of grief through a white gaze, a white predatory gaze, and an audience that’s expecting you to act in a particular way and demanding that. And so grief, it seems to me, goes along with the question of the body and how you’re speaking about it in this book.

Abdurraqib: Yeah, and The Crown is funny, because that’s like a concept book, where the person in the book is like a funhouse mirror version of myself. That’s, in some ways, the way I always write, but even more so in that book, where it’s kind of like, that character, so to speak, has very real trappings of my life — lost a parent and grew up in a neighborhood that is my neighborhood and had a barber that is very much my barber — all these things. But I needed that distance more than I normally do, to say, OK, this isn’t my exact life. These are exaggerations of a life similar to mine, close enough.

Ó Tuama: And was that for safety, Hanif, or was it for all kinds of artistic reasons, or for a variety of these?

Abdurraqib: Some of both — yeah, I think safety is the primary reason, but also for artistic reasons or for reasons of — you know, I think that distance allowed me an ability to make and create and think about the speaker in a way that was detached from myself, and so I didn’t have to feel beholden to making like, a documentary. I didn’t have to feel like I was creating something that had to be airtight and strict in that way.

Ó Tuama: You have written quite extensively really, about anxiety, and I’ve noticed a profound vulnerability and generosity in the essays that you’ve written about anxiety. Are you happy to talk about that and to consider it?

Abdurraqib: Of course.

Ó Tuama: I mean, would you be able to speak a little bit about the way that you speak about anxiety and what you offer through your essays, for that?

Abdurraqib: Yes — I mean, I have a couple different anxiety disorders that I was diagnosed with in my 20s, though had been feeling the effects of for much longer than that. But you don’t know — for me, it’s hard to pinpoint — I grew up playing sports, and I would be very nervous a lot of times, in that process, but would just think, well, this is just — everyone feels this way. The stakes are high, and I’m playing a tense game, so everyone should feel this level of nervousness. And then that started to translate to my social interactions, but I thought, well, you know, social interactions can be tense, and so this is just the way that people feel.

But I began having large panics — large, actual, very real panic attack-type situations, in my 20s, and was diagnosed with a couple anxiety disorders, and depression that was kind of fueled by those anxiety disorders. And I think this pushed me to become more — to work on the levels of emotional awareness that I was operating with — and, again, to be generous with myself and what I know I’m capable of, and also to think about anxiety as something that is just built into my world. It’s like a — it operates at a low hum at all times, and some days the volume is just louder than others.

Ó Tuama: You spoke about that volume being turned up and down, being controlled by a small and experimental child, which made me burst out laughing and then also feel frightened about this experimental child.

Abdurraqib: Yeah, yeah — I don’t have control over the volume. And I think, honestly — gosh, I do think reentering the world, in whatever case that may be, for me — it’s funny, I got vaccinated a bit ago, but my life hasn’t really changed much because the idea of going into the world is still a little alarming, you know? And I think that I am not yet prepared for that.

Ó Tuama: Yeah, because I know that anxiety can either make you want to be completely isolated or completely immersed. And in a global pandemic, where isolation and immersion have come under enormous kinds of political and policing gazes, this is a language that many people are and will be speaking over the next few years, as more and more people get vaccinated, but then do the complicated work of trying to figure out what social interaction might mean, what consent might mean. What wisdom do you have, as you think about what that might mean for you? Or are you discovering that yourself?

Abdurraqib: I think I’m discovering that myself. I’ve spent the majority of this pandemic living alone, just me and my dog, and … [laughs]

Ó Tuama: Wendy.

Abdurraqib: Wendy, yeah, dear Wendy, who has been — I had Wendy before the pandemic. I had Wendy in 2019. But she’s been an excellent pandemic companion, though. She has become — she’s also an anxious dog. And so she has anxiety, and we’ve become a bit attached to each other. She has become more attached to me than she was before, which I think I have some worries about whenever people begin to slowly make their way over to the house and all that. But I think, for me, it’s coming to terms with how comfortable I feel being close to people, which I do believe in a type of closeness with the people I love. And to have not seen so many of them in so long, it’s challenging, but really a challenge I feel like I’m up for.

Living — I don’t want to get too, perhaps, dark or whatever, but to be alive is to immerse oneself in either the potential for suffering or a very real, constant and present suffering. And so then, for me, the questions have to become about how does one survive in the midst of that suffering, in the midst of knowing that living presents endless opportunities for suffering and sometimes fewer opportunities for pleasure? And so the question then becomes, how can life — not only how can I survive, but is there a way that I can express an investment in shared survival, one that both uplifts my living and the living of others?

Ó Tuama: And there was a series of letters that were published between you and a friend, Dr. Eve Ewing, that were so moving. And in one of those letters, you spoke about music. You said, “It always occurred to me that the music was worth writing about with reverence. I had watched music, had a love for it, dragged so many of my friends back from whatever ledges they were standing on. And if there’s anything that has kept my people alive for longer than they might have been alive otherwise, then I believe it is worth honoring.” That seems to be ways to live a life, for you, Hanif.

Abdurraqib: Gosh, I forgot about those letters. I did love writing those, and Eve and I did an event last week which was really great and really wild because, you know, we haven’t seen each other, physically, in so long. For me, I’m aware of how life has been difficult, and because of that I’m acutely aware of the things that have felt to me like mercy, or felt to me like something that has helped me get through. I am very serious about honoring that getting-through and the tools that help one get through, because those are other things; that’s something else that is not promised. And none of us are promised to find a thing that will lessen our suffering. And so to find that feels vital — to uplift it when you find it.

[music: “We Will Rebuild with Smooth Stones” by Balmorhea]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett. Today on On Being, poet and cultural critic Hanif Abdurraqib, interviewed by poet Pádraig Ó Tuama.

[music: “We Will Rebuild with Smooth Stones” by Balmorhea]

Ó Tuama: You’re speaking now, Hanif, and you write, also, about the griefs that you’ve lived through — the systemic griefs, as well as the personal griefs from within a family. What’s it like for you to offer these griefs as moments to reflect on your life, but in quite a public way even though they’re private things?

Abdurraqib: It’s interesting, because I think I’m a pretty private person. And so there are elements of my work that feel public, but I do think I’ve gotten very good at the dispensing of information — figuring out what information to dispense where and when, and through that becoming very good at withholding and knowing what to withhold, which is why I almost appear as a funhouse mirror version of myself in so much of my work, because I’m thinking really clearly and thoughtfully about sharing and withholding and how that, too, is a process. Because there’s a great deal of, I think, mystery behind my life and living, which is by design. I am, ultimately, a very private person. And I like to be — I like to keep some things for myself when I can.

Ó Tuama: john a. powell — in another life, I worked in conflict resolution. And john a. powell offered some questions once, at a gathering I was at, when he said a way of examining the question of power in situations of conflict is to ask three simple questions — who decides? Who pays? Who wins?

And I’ve thought about that so often in conflict resolution settings, and I found you asking that over and over again, not just in A Little Devil in America; also in your other essays online, as well as your books of cultural criticism, where you begin to ask, what is the contract that’s happening in this moment of cultural experience, and who’s paying the cost? And maybe it is the person from whom much has already been taken.

Abdurraqib: And what do we do when the contract is broken? I mean —

Ó Tuama: Yeah, because there’s no recourse in unwritten contracts, are there. You can’t go back to it to say, check it out, I’ve got rights here.

Abdurraqib: I mean, in some ways I’m struggling today because of the news of Adam Toledo, which I have been struggling with that for a while. I didn’t watch the video, but the understanding of the bodycam footage introduced a new level of that struggle for me. And a major frustration I have is that the mayor of Chicago got up in front of an audience of reporters and said, “Well, we hope people will be calm.” And I think, what a foolish thing to say, when police murdered a 13-year-old with his hands up. Granted, in the States our social contracts are flimsy and don’t mean anything anyway, but — you know, they’ve been broken many times over and don’t really hold any water — but that’s beyond the point I’m trying to make here, which is that when they are broken so explicitly and egregiously and many people lied to uphold their breaking, including that mayor, I don’t really want to hear a call for calm. That doesn’t make sense to me.

Ó Tuama: Yeah.

Memory is so much part of your work. I read — let me find the quote at the back of one of your books. In Crown Ain’t Worth Much, in the notes of that, you spoke about “This book is dedicated to the memory. The memory of any moment you have loved or been in love, and the people who lived in that moment with you. For my mother, for the changing city I once knew and the one I love still,” and then Tyler and Mike and the barber shop, and you mention other people, too. And I’m so struck by how, in another place, you say that you’ve “given up on wanting to bring back the dead, especially to a world that isn’t any better than when they left it. But I do long for the moments when they were alive.”

And that is a private grief, but it’s also a public calling to attention and a public acknowledgement of the very thing that you’re talking about, to say, what is the possibility of mourning in a world where you’re actually not sure you’d want the dead to come back to it, because the world isn’t interested in changing for the benefits of Black populations?

Abdurraqib: Yeah, but I will say that I think I’ve learned to mourn in a way that just isn’t rooted around sadness and/or longing for a return. And that feels better, because I think I’ve learned to mourn in a way that is celebratory, that is expressing gratitude for the real gift of carrying the memory of someone who is not here anymore — and not only carrying that memory, but carrying everything that person gave and carrying everything I learned from that person while they were still here. And that’s a type of mourning, but it’s a type of mourning that I think serves my better impulses. You know, I will not be here forever, and everyone I love who’s here right now won’t be here forever, and it feels important to set up tools through which everyone I love can be mourned in a really luminescent and complete, fulfilling way.

[music: “From Home, To Work, and Back” by Tall Black Guy]

Tippett: Hanif Abdurraqib is the author of two books of poetry. His books of essays include Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest, and his most recent is A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance. He also hosts the podcast Object of Sound.

Pádraig Ó Tuama, who interviewed Hanif this hour, is the host of the On Being Studios podcast Poetry Unbound — and one of Hanif’s poems is featured in the first episode of a spectacular third season, which has just launched. We are so happy to have Pádraig as the staff poet and theologian for the On Being Project. His latest book, just published in a U.S. edition, is In the Shelter: Finding a Home in the World.

[music: “From Home, To Work, and Back” by Tall Black Guy]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt, Gautam Srikishan, and Lillie Benowitz.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project.

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

The Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

And the Ford Foundation, working to strengthen democratic values, reduce poverty and injustice, promote international cooperation, and advance human achievement worldwide.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.