James Bridle

The Intelligence Singing All Around Us

You might want to take a walk with this one. It is big and full of brain food and an enlivening opening of imagination to possibilities that are emergent now: the notion of the “broad commonwealth of life” that we are “inextricably entangled with and suffused by”; the paradox that the more accurately you try to measure some things, the more unmeasurable they become; the way words we use all the time have kept our cellular belonging to the natural world alive, even as civilization forgot.

The technologist/artist James Bridle brings all of this into interplay with an intriguing, refreshing lens on our lives with technology — and with all that artificial intelligence is and might become.

You might not think of intelligence the same way again, or the truth of mythology, or the letters of the alphabet, or what it means to be human. And you will smile next time you access the place where your digital life is stored and realize what it says about us that we named it The Cloud.

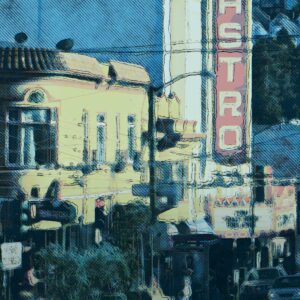

Image by Danyang Ma, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

James Bridle is an artist and technologist and author of the books Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence and New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future. Their writing has appeared in The Guardian, Wired, The Atlantic, and many other places. Their art has been exhibited around the world, including at NOME Gallery in Berlin.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

Krista Tippett: These are some of the words and ideas that are brought into conversation with each other in James Bridle’s writing, and that drew me into conversation with them:

The notion of the “broad commonwealth of life” that we are “inextricably entangled with and suffused by.”

The paradox that the more accurately you try to measure some things, the more unmeasurable they become.

The interplay between intelligence and consciousness and our belonging to the natural world at a cellular level. The way words we use all the time have kept this interplay alive in us even as civilization forgot.

And an animating entry point to all of this for James Bridle is our lives with technology and what artificial intelligence can and can not do.

You might want to take a walk with this one — it is big and full of brain food and an enlivening opening of imagination to possibilities that are emergent now. You might not think of intelligence the same way again, or the truth of mythology, or the letters of the alphabet, or what it means to be human. And you will smile next time you access the place where your digital life is stored and realize what it says about us that we named it “The Cloud.”

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

James Bridle is an artist and technologist and author of the fascinating new book Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence. They live on the Greek island of Aegina and spoke to me from Athens.

Tippett: There was some serendipity in me reading your book and getting to really delve into it the way I did. Obviously, I read a lot for my work, but I was getting ready to go on essentially a sabbatical for 10 weeks. And the copy I have of your book that is completely marked up is a galley copy. And it was sitting there and I was kind of picking up books saying, “Let’s see what’s come in that I might take with me as a big read this summer.” And I was heading to Patmos, to the island of Patmos.

James Bridle: Oh, lovely.

Tippett: And so I saw that you were in Greece and I thought, “Oh that’s it. It’s meant to be so.” So I’ve been with you, I’ve been thinking with you and learning from you for a few months now and it’s great to finally speak.

Bridle: Well, that’s lovely to hear. Thank you. I’m glad it’s been of interest and it certainly sounds like it mirrors a bit some of the sort of synchronicities that went into writing it the first place, which has been a whole train of bits of the universe coming and knocking on my door and saying, “You should probably pay attention to this thing right now.” And occasionally listening.

Tippett: That sounds right. I would just like to know a little bit about — are you from London? Is that right? Did you grow up in London?

Bridle: Yeah. I grew up in London, I’m British from there.

Tippett: And in your person and in your work, you bring together disciplines that aren’t necessarily in a robust conversation: art, technology. I wonder if in the world of your childhood and your earliest life were these fascinations planted in you and were they planted together in some way?

Bridle: I don’t really find that in my childhood, I’ll be honest. In that, I grew up in a very urban environment and also in boarding schools in the countryside, which are terrible things and don’t make you love the countryside in any way at all. And actually the main route that way of my work would be the internet, which arrived when I was kind of 12 or 13. So I always say that I grew up with the internet, and I’m one of that band of people who straddle it a little bit. And so I have a, I think, a particular feeling for technology, which perhaps our parents’ generations will never have and that younger generations will never know because it’s always been present. So we have this quite odd personal relationship with it, I often think. And I just go where my interests take me, essentially, and this is where they’ve taken me in the last few years.

Tippett: Before I really want to focus on the Ways of Being book and everything that’s in there. It’s so rich. And, just to note, that your last book was the New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future. So spoiler alert, there’s a lot of pointing in that title at the fact that it was a book that had some caution and pessimism about our lives with technology.

Bridle: Yeah, it’s not a cheery book. It’s not a book I recommend to people if they want to feel particularly good about the world.

Tippett: But I think that this new book, just to what you just said, there’s so much in it about life writ large and intelligence writ large and all we’re learning in those directions. And I think in the introduction you have — And I’m a big believer in questions as a form of words and the power of questions and how questions orient us. And there are a couple questions you have that to me felt like operating questions, orienting questions and you could say everything that follows takes off from: “what future is being imagined here? And what intelligence is at work?” And I’m curious, were those questions that you began with or did they emerge as lenses through which you were exploring what you were seeing?

Bridle: Those are definitely kind of foundational questions for the book. And they do come out of all the work I’ve been doing previously. You bring up New Dark Age, and that was really an inquiry into what has gone wrong with the technologies that we thought we were building, that were supposed to be — or we were told were going to be, and we naively maybe believed were going to be — in some way, emancipatory and community building and knowledge enhancing and all of these lovely ideas and how that really hasn’t been the case. And New Dark Age was an inquiry into how that came to be and the state that we’re in. And Ways of Being is very much one way, a very personal way for me, out of a fairly dark place that book took me to. I felt that in order to reframe this question from being, “How did we get to this bad place?” into essentially, “How do we get out of it?” There’s two parts to that.

The first part is this question of: what future is being envisioned? How exactly we frame — how we understand really, truly what it is that we’re building, and then how we imagine alternatives? A really clear-eyed view on exactly where we are in the things that we make and the relationships we have with the world around us. And then a reasonably clear vision of the alternative that might be possible to that.

And that second question, “What intelligence is being envisioned here?” is really a question about the nature of intelligence itself. Because what I realized was this term “intelligence” was being used everywhere and people weren’t really questioning what that meant and were taking, so often, the definitions that they were given by other people as being definitional, as shaping the entire discourse that was possible around that. And absolutely shaping, as a result, where we would find ourselves in the future. And I realized that by troubling that definition somewhat other futures could be envisioned, could be imagined, or, in fact, even other presents.

Tippett: And this is just bringing back to me that I wasn’t sure as I started into all that you’re kind of collecting there, that intelligence didn’t feel like a big enough word to me. And one of the larger contexts of also why and how that language of intelligence became too small. Really, I think the story you’re telling, and I just want us to start — talk about this story. So when you say “options,” that there are options, it doesn’t have to be this way or there are other futures that can be imagined: this is all unfolding. This is not a cerebral intellectual exercise about what could be. You’re telling a story of our time, a multitudinous interactive story of our time. But in some ways I think it’s probably important to put on the table that seeing this story and investigating taking it seriously does also mean getting conscious of really the Enlightenment way of thinking and seeing that all of us are still so formed by, certainly, the 20th century was shaped by 18th, 19th century, which had so much to do with taking things apart and seeing the differences between them and ordering and classifying, and that as a framework as how the world works.

And one of the just core realities that you then go on to investigate and describe in all that we’re learning now about how the world works is that the closer in all that we’re learning now about how the world works, “the closer we examine” — this is you — “and the more forcefully we interrogate and attempt to classify the world, the more complex and unclassifiable it becomes.” And actually that science itself, in our generation, is breaking down those taxonomies and what got reduced. And that’s a big piece of the story you’re telling. And it’s also something that I’m just so fascinated by. And I feel like amidst all that we have to be discouraged about, realistically, it’s one of the most wonderful and thrilling and hope-giving aspects of being alive now.

Bridle: Absolutely. When you were speaking there about this kind of unfolding that we are always part of, the image that sprung to mind for me was particularly the fact that we live within these kind of multiple overlapping timeframes of understanding. By which I mean that, like you said, there’s a process that’s happening within science now that are undoing the work of previous generations of scientists and the frameworks they built — or at least if not fully undoing them, shaping them into radical new forms. But just to the point when those frameworks only really just being understood more widely by the public or by any of us who aren’t like ourselves at the cutting edge of scientific research.

And at the same time, there’s still even now this deep divide between the humanities and the sciences, which produce deeply differing worldviews and understandings of what’s happening. And also the huge split you’ve obviously already alluded to, which is between the dominant western sciences and non-western, non-dominant understandings of the world. And all of us live within some different overlapping fraction of those things in some weird bit of the Venn diagram of understanding between these things that are both different ways of framing the world, but also parts of the same process at different stages. I think too, the phrase — the evolutionary, Lynn Margulis.

Tippett: Oh yes, and I first heard about her from Robert MacFarlane, but it’s one of these names that then comes up everywhere. So she’s important in what you’re saying.

Bridle: Well, I just particularly wanted to just repeat that phrase of hers, which is that everything is equally evolved. That’s a really resonant phrase for me that was really important in my thinking.

Tippett: Everything is equally evolved?

Bridle: Everything is equally evolved. Everything has been, everything has been on this planet for as long as everything else. Everything has been in this universe for as long as everything else. Nothing is more evolved than anything else. Everything has been evolving for the same length of time. Everything has been becoming for the same lengths of time. So while we live inside this unfolding, and we live at different levels of it and different levels of understanding in different parts of that process, that simple scientific, but also deeply, I don’t want to use this word “spiritual,” just mean a deep quality of being in this universe, is that everything is part of that unfolding process that is still going on and that is still one of learning. And that immediately destroys any idea of hierarchy or division for me that might shape or inform that splitting and clumping that’s been the last century of scientific legacy and that we are finally getting rid of.

Tippett: Even just back to that idea of intelligence being too small. One of the things we’re learning is that these decisions we’d made about what was intelligent and what was not, and our superior human intelligence over against all other intelligence is just being radically opened up. I think Robin Wall Kimmerer said to me, “I can’t think of a single scientific study in the last few decades that has demonstrated that plants or animals are dumber than we think. It’s always the opposite…We keep revealing the fact that all kinds of creatures have a capacity to learn, to have memory, and that we’re at the edge of this wonderful evolution in really understanding the sentience of other beings.”

Bridle: That’s another way of stating Richardson’s paradox, right? Which is what you mentioned earlier. This thing that when you look deeply…

Tippett: So I wanted you to talk about Lewis Fry Richardson. I wanted to actually ask you.

Bridle: …Oh, I’ll talk about him endlessly. I’ve very happy to.

Tippett: Go on.

Bridle: Okay. Well, I first got deeply into Richardson’s work because he was one way of understanding for me actually what happened with technology in the 20th century in that he was a meteorologist who was doing a bunch of meteorology work before the first World War. And then during the war, with pencil and paper, he did some of the first mathematical calculations of what would become contemporary meteorology. To predict the weather using maths.

But Richardson stayed interesting throughout his life because as a pacifist, as a Quaker, he kept doing these kind of weird, interesting pacifist things, like writing several books in which he tried to establish a mathematical basis for pacifism.

Tippett: He tried to calculate if the distance of borders or something had more, made war more likely or something?

Bridle: That was his idea. He basically thought that the likelihood of two countries going to war was a function of the length of their shared borders. And so in order to prove this scientifically, he had to find the length of all their shared borders. And he wrote to all these countries and looked it up in almanacs and went through The British Library and all these kind of things. And he discovered that all the lengths were different, and no one knew the lengths of their countries at all. And as a mathematician, this really bothered him. So he started trying to figure out why everyone was measuring the lengths of their borders wrong.

And he discovered that it is impossible to measure the length of a border, because if you use a ruler that’s a kilometer long, you’ll miss out on all the squiggles along that route. And if you use a ruler that’s a meter long, you’ll miss out on all the tiny little divots in the coastline that are within that meter, if you think of the kind of wavy line of a beach. And what he discovered is the smaller the ruler you use, the longer the border gets. And what he discovered 20, 30 years before Benoit Mandelbrot described them, was fractals, these things that become more complex, the deeper you look at them.

Tippett: And Mandelbrot was — that equation came out of Lewis Fry Richardson’s work or was inspired by it. I didn’t realize that.

Bridle: He’d seen Richardson’s work and that thought there was something in that. For me — I can’t speak to its scientific value though, I know it’s kind of referenced in all kind of way — but for me, it’s one of just the greatest realizations. And one way it’s a way of resisting these kind of hierarchies by saying that if you look at something more deeply, it’s going to become more complex and nothing’s ever that simple. But also nothing is ever that simple, and that’s wonderful and exciting and it makes everything really, really fascinating and interesting because there is always more to discover if you pay more attention.

[music: “Dream Her Voice” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: Here’s the way you wrote about Lewis Fry Richardson’s paradox. You said, “Instead of resolving into order and clarity, ever-closer examination reveals only more, and more splendid, detail and variation,” which struck me as a statement about life as well as the measuring of a border.

Actually, I want to come back to Lynn Margulis. Her work also illuminates these things we’re talking about in other ways. One of the things she said was that “life did not take over the world by combat but by networking.” So, as you said, some of science that’s being undone is at least simplistic descriptions of evolution and survival of the fittest. And would you talk about this idea of “endosymbiosis,” which also is a new way of seeing vitality and even ourselves?

Bridle: Yeah, with the very strong caveat that I’m not an evolutionary biologist, I probably may get huge numbers of facts about this wrong in explaining it, which I tried to research much, much harder for the book but I’m just talking now. But endosymbiosis is Margulis’ framework for understanding how complex cells, the cells that make up our body and all other living organisms, how they first emerged. Symbiosis itself is the process of two things coming or working together. Endosymbiosis is the absorption of one by the other. And Margulis’ theory that’s pretty strongly supported these days is that the complexity of, for example, the animal cell is an endosymbiosis of what used to be multiple smaller organisms so that the nucleus and other kind of organelles within the cell have gradually kind of accreted into one organism. But in fact, the cell itself is at that level, at the level of the individual cell, a tiny community of different organisms that millions and millions of years ago decided to cooperate and work together within one tiny community. And then they built up into larger and larger and larger communities. And that everything in fact has been built out of these kinds of communities of organisms working together.

And that scales all the way up to the human body that, as we’re more and more aware of, is now this kind of walking assemblage of beings. We carry around, this kind of two and a half kilos or whatever it is of other creatures within our bodies, in our gut, and on our skin. And to even speak of ourselves as individuals, scientifically, is starting to prove harder and harder as scientists make really extraordinary discoveries about things like the fact that our intelligence, to use that word, as it is measured by science, is highly dependent upon the health of the creatures in our guts. We have a symbiotic relationship with our gut that isn’t just about digesting food but is also about how we think, how we fend off disease, about all these other things. We are communities in and of ourselves.

Tippett: Yes. It’s so fascinating. Also, by some measures, there may be more microbial cells in a human body than human cells. So to even say that we are fully human —

Bridle: Yeah, we increasingly find it difficult to draw these distinctions I think. I remember when I first learned that this — or two of the facts I think that most blew my mind reading this, one of which is that: it seems likely that the atom or the cell originally came from the closest free-living relative to the cell and the center of our cells today is the typhus bacillus. Something that we kind of fear as a sort of destroyer of life is also our kind of great, great, great, great, great million times grandmother at the center of our cells.

And also that even things that have been incorporated into our actual DNA, into our written instructions, have come from the outside. That something like some 30, 40 percent of the human genome hasn’t evolved as we understand it in most of our basic understanding of science but has actually been written into it by viruses including most of our reproductive system, including particularly the placenta. The mammalian placenta was written into the DNA of animals multiple times billions of years ago by other viruses coming from outside the mammalian line. So in all of these ways, we’re just products of our environment, not just in a kind of sociological sense, but in a very, very deep fleshly embodied sense, that we are this coming together of so much life.

Tippett: Here’s another couple of sentences from you that I really love: “Life is soupy, mixed up, and tumultuous. Muddying the waters is precisely the point because it’s from such nutritious streams that life grows.”

Bridle: Indeed.

Tippett: I was also really fascinated by your description of Pando, which seems to me that was just a single clonal aspen, one of the largest and oldest individuals on earth, and yet defying again the notion of an individual. Would you talk about — because I wonder if something like Pando is also something that we literally could not see before we had some of these lenses on that you and I have been talking about.

Bridle: Yeah. Pando’s such a beautiful example of exactly that. So our idea of a tree is something that is above ground, that is the trunk and the crown because that is what we see. What we have failed to see, most of us have failed to see, for most of the time is the connections underground. And in the case of Pando, these connections are very explicit in the fact that there is one single root system that underlies tens of thousands of what we see as trees.

So what we see at ground level is a forest of aspen trees, but that forest is one single organism. And each tree is in fact a shoot of a common one single root system. So they all share the same DNA. They are in fact one organism. And this was not recognized, this was not seen until the 1950s or 1960s and is, for me, a great example of this kind of complete reframing of what constitutes an organism but also such a clear illustration of the narrowness of what we see and extends well into — not just a kind of huge clonal organism like Pando, who is possibly one of the largest, heaviest, oldest creatures of any kind on earth —

Tippett: It says between eighty thousand and a million years old. [Editor’s note: Some experts say Pando cannot be more than 12,000 years old.]

Bridle: Yeah. But also gets us into the much more complex symbioses that are happening in all forests between trees and fungi and the communication that’s been happening between them that we are only just learning about, most of us, again, within the dominant traditions, et cetera.

We’re shaped by what we can perceive and what we can perceive is shaped both by the tools that we have to hand, our physiognomy, but also our imaginations and the culture in which we exist. But it doesn’t take much pushing on those things to change those perceptions, I think, in really interesting ways.

Tippett: And as we touched on when we began speaking, we’re talking about a lot of disciplines that are themselves unfolding and also unfolding in conversation with each other. And you’ve been on this kind of sweeping investigation and where your work and your entry point is distinct and I think builds on others, is that you come at all of this from the perspective of a fascination and engagement with our lives with technology. And I was very struck by this story you told about walking with Suzanne Simard in a redwood forest outside Vancouver — Suzanne’s also been on the show — and taking in a kind of kinship with the internet. And you were thinking about the mycorrhizae, the kind of underground networks, nodes and life, energy, flow.

Bridle: Yeah. It was one of the key moments, I think, kind of an awakening for me in which a previous silence was essentially broken where I took the earmuffs off or whatever it is, and suddenly everything broke into song. And just by a very small shift in awareness, the world starts to speak in a way that it really hadn’t before. Not necessarily immediately, but just by letting those kind of various encounters sit with you. And discovering indeed, as I think maybe you were pointing out, that there was this deep relationship between our coming to understand the mycorrhizal networks and our construction of technological networks of the internet. It was necessary for me to make that connection. That story being, if you want me to briefly outline it…

Tippett: Yes, please.

Bridle: There is a very definite connection between these two things in that the first researchers to recognize and start to map out these mycorrhizal networks in the 1970s and 1980s were also some of the first people to be connected to the nascent internet because they worked within national research institutes and universities, which were the first places to be connected to the internet. So they were some of the first people to build mental models of networks in the way that we currently understand them.

And the development of the internet also led to not just these new kind of metaphors of interconnected nodes of the network as we’ve come to understand it, but also methods of analysis. So beginning in the 1980s, people studying the internet developed a whole new kind of form of mathematics called network theory, topological studies of how complex networks interacted, that there simply wasn’t a mathematical description for before but people realized almost immediately they could apply to these mycorrhiza networks. And they became another way of seeing and understanding them even more deeply.

And what I really understood from that was that, as humans, we’re not that great at really paying attention to things outside our own minds, perceptions, immediate experiences, and things that happen to us. We quite often seem, and I don’t fully understand this process but I see it happening all the time, we seem to need to build these of internal models of the world and our own little toy-like creations in order to see the things outside us. And that seemed to be what happened with this kind of development. We didn’t develop the internet in order to understand the trees. There’s something more interesting and complex going on there, but it happened. That’s how it worked. We had to build our own little networks before we saw the networks that already exist in the world. Just as it feels to me, as I describe in the book, we need to build our own models of intelligence, however, we can pour in artificial intelligence, in order to see the intelligences that have been around us all along. Maybe that’s why we’re doing the AI, pushing us towards it.

And maybe —I’m just thinking this now. This is probably incredibly naive of me because, of course, that’s what we always do. We have to make these stories about what the world might look like in order to map that back onto the world again and make those things true essentially to figure out our path towards them — So maybe that’s what AI and network theory actually are. They’re just new stories about the world that make that kind of world accessible to us properly again.

Tippett: Yeah. And I think our brains are working so hard to create order out of chaos so that we’re not completely overwhelmed by everything. But it also means that we’re limited in what we see. Also, I’m just thinking in this connection — as there are advances like the ones we’re talking about of seeing more reality and it also makes sense to us, then hopefully that means that collectively our brains can start to see different. Starting with this idea of yours, how does the world work, that we start to have a different sensibility about that.

Bridle: Yeah. I think as long as we also manage to maintain an awareness and ability to comprehend or at least live with the unknown and the unknowable, I think, because it’s this fascinating, endless back-and-forth balance between wanting to make sense of the world and trying to understand it and, as you said, reduce this noise, reduce this complexity so that we can live meaningfully within it. While at the same time, there’s always something potentially destructive in that, as we’ve seen in the kind of history of science, this kind of attempting to frame everything within a particular theory. So it collapses again. And I think there’s something so fascinating in that tension because that’s where we always live: wanting to make sense of it but not wanting to reduce the world, to some extent, that it stops being kind of interesting or like itself anymore.

Scientists in the dominant tradition are also, a lot of them, they’re the people most comfortable living with doubt that most of us are so bad at living with because that’s where they live all the time, really on the edge of understanding stuff. And they know more than anyone else that there’s huge limits to what we can know about the world. So that’s something I think we can learn from a lot of scientists.

[music: “Dream Her Voice” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: You work with this language of “the more-than-human world.” This is more language of you: the “broad commonwealth,” as you said that, of the non-human life with which we are inextricably entangled and suffused by, and these are “companions on the great adventure of time and becoming.” I know that that phrase was originally coined by the philosopher David Abram. I wonder if he was speaking more in terms of more-than-human, in terms of the natural world. I know for you, it’s animals and plants and it’s machines. Is that right?

Bridle: It’s animals, plants, machines. But it might also be ecosystems and inorganic life as well and much else. I mean, I love the phrase. I find myself using it less and less because I still want something that doesn’t have the word “human” in it to talk about what I’m talking about. The beauty of the phrase is it kind of points towards the non-human without negating the human that reminds us that our perception of the non-human is always rooted in the human, but that the human is not necessarily at the center of everything. So it is a really good phrase for that. But I do yearn for something that really is a way of talking about agential life — life that is up to something that’s bubbling around and doing stuff, and that we can meet and have conversations with that — Yeah, I’m just always looking for that.

I guess maybe what I’m doing more now is actually looking to have those conversations. I think that’s really the thing that has to follow. A lot of where I go in the book is towards, not just ways of thinking or ways of being, but actually ways of living with meaningfully and in justice and in peace with other beings. And that really requires a very direct engagement with them, and meaningfully, actually talking to other creatures, other beings. And so how we do that, how we address them, how we think of ourselves and others in the relationships that we might have. That’s more than maybe just words. Or at least, they’re words that will only emerge from those conversations rather than ones that we make up to try and frame them is maybe how I’d put it.

Tippett: And I think one of the things I loved most about your writing, and this is also a fascination of mine, is the importance of language in walking that path. My understanding was, I think from you, that this phrase, “the more-than-human world” was, in the first instance, about that language itself is a way that we reorient. And I think some of the things that I just so love about what you have investigated is how language itself, in ways we’ve rarely paused to consider, is this reminder that we’ve carried with us all these millennia of the fact that we are part of the natural world, not in it. I’d love to talk about some of that. The move — so onomatopoeia, which I think is something one learns in school, but how that is reminding us where we got sound from and what our — where we learned language.

Bridle: Yeah. So what I talk about in the book is these first theories of language origin, and I draw heavily on David Abrams. You’ve mentioned particularly his book, the Spell of the Sensuous, in which he talks about the body’s relationship to the world, that we’re only capable of making the sounds we make by drawing them into our bodies. And the sound of language itself is shaped by the armature of our kind of muscles and rib cages and the structure of our throats. Or the fact that our actual writing systems still contain these elements of the natural world. He talks about the very early scripts, kind of Syriac, pre-Egyptian pictographs that were mostly essentially pictures of animals. The aleph that became the A was originally a bull’s head. The quoth that became Q is a monkey tail. These things, we’re basically still drawing tiny pictures of animals, even though the words we make have lost all their reference to the natural world.

Tippett: When I was reading you, I started to feel this move from, as you said, pictographic language, which made clear this belonging and origins — to the phonetic alphabet, which really was a form of estrangement for human beings.

Bridle: Yeah, the pictograms describe the world as it actually is. If you draw a picture of a thing, you are referring to that actual thing. And slowly, even though those pictograms came to represent, by ancient Egyptian times pictograms, they start to represent concepts more than things, but they are still rooted very much in pictures of actual things. Once the script becomes kind of Latinized, it actually refers to the sound of language. The letters are not things themselves, they’re ways of pronouncing words that mean other things.

So that the whole language, which is also how most of us think, but not all of us, crucially, starts to remove itself and become something that refers only to itself and only to the human. And so it takes this kind of immense effort, all this invention of words that we’ve been talking about, “the more-than-human” and all this, really convoluted ways we have of trying to express ourselves. Because we’re kind of fighting this kind of prison of language that we’re stuck within that is constantly trying to separate us from the world. It’s no accident that all the great religious spiritual traditions teach silence and awareness and clearing one’s mind and trying to get away from this constant process of language, which is a constant process of estrangement…

Tippett: And the space between the letters.

Bridle: …it’s a constant separation of oneself from the world. And you can do magic and wonderful things with it, of course. But there’s also, for me, the heart of it is always this kind of apophatic tradition, this tradition of pointing towards that which is unspeakable and unsayable because it cannot exist within language. Because language as we understand it is something unique to humans. And the truth of the universe is not unique to humans. So it cannot be expressible in language.

Tippett: I do think that’s also a wisdom of spiritual traditions, that understanding the limits, the limits of language. One that was so fascinating to me is the letter M. This is so stunning. And when you’re talking, you have the pictographic to the phonetic that the letter M, our letter M is derived from the Semitic letter mem, the Hebrew word for water, mem was drawn as a little wave. So that M is, and you can still see that. You can see it as a wave if you see it, if that is presented to you that that’s what it is, then I see this letter that I use all the time completely differently.

Bridle: Yeah. The M is a wave and the O is an eye, as in the Eye of the Oculus, the Q is the monkey, the A is the bull. They’re there. They’re just living, just dancing around in the things that we are trying to write and say right in front of us. And we are using them for all these complex, abstract ideas. And they’re kind of just sitting there winking at us the whole time.

Tippett: Reminding us who we are. [laughs] And then you make me so aware that we call, we name, we are still naming things out of this primal place in ourselves, right? The worldwide “web,” or the “cloud.” The cloud.

Bridle: It sneaks up in all these funny ways, doesn’t it? Because we have no way of describing things other than the way the world has taught us to. It’s the languages, the theories of some of the older theories of the languages that I talk about. I’m not going to remember them all unless you have to work in front of you, which I don’t. But these theories that were put together for the origin of language in the 19th century, which were kind of, what is it? It’s like Hoo-ha theory and Bow-wow theory and these different ideas that language evolved from the grunts that we made when we were exerting ourselves, or the noises that animals made, or the very serious proposition that’s been put forward by a number of anthropologists that we first made noises in order to call dogs. But that was actually something that preexisted the form of language but made us need to call. So maybe the first people we spoke to were actually non-humans. That there’s always been, the language has always been a kind of calling out to the world. And the world is always kind of speaking back to us, as you say, through language, even when we’re talking about the most high-tech things imaginable, like the web and the cloud, because those are the things we have to think with. Those are the things that originally taught us to think at all.

[music: “Strange Dog Walk” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: Coming back to being in Greece where you live now, and where I was when I read this book. I had this sensation there that the mythology is practically like a natural element. It almost felt like it’s in the air, and it’s in the ocean, and it’s in the soil. And you tell this amazing story about — and of course mythology, somebody said the other day, mythology is what is more than true. Or, I like the definition of a myth is not something that never happened, it’s something that happens over and over and over again. But you had this amazing story about nymphs — the order of the naming of a chain of islands in mythology.

Bridle: Yeah.

Tippett: So that as we’ve been talking about, language carries truths that science catches up with or we catch up with. And it feels like there’s a similar thing to say about mythology in this story.

Bridle: Yeah, absolutely. So that story is told partly in geology, which is that 14,000 years ago, at the end of the last ice age, the Saronic Gulf, which is the kind of large body of water which connects Athens to the main Mediterranean. The Mediterranean was much lower, and the islands that now poke out of that Gulf, one of which I live on, formed a kind of land bridge separating the sea into a series of lakes. And then over the subsequently few thousand years, the levels of the Mediterranean rose, and that land bridge became a series of islands.

But as has been pointed out by what some people call geomythologists, which is just a wondrous term, is that if you look at some of the sources in ancient mythology, like Hesiod and his Theogony, which kind of tells the long story of how all the gods came to be, you’ll find that these islands are named after nymphs. And the order in which they were sired, the order of their birth — from, in this case, someone whose name was King Asopus, which is the name of the major river that used to flow out near Athens — the order of the birth of those nymphs corresponds to the order with which these islands would’ve emerged from the ocean. And so it seems like the myth retells a geological history that’s 10,000 more years longer than when the myth was recorded by Hesiod. But why not? People were there, people witnessed this thing happen, or generations of people witnessed this happen. Someone was there at the moment that bridge became an island. Someone, some person might have seen. There were fewer people around, but some person could have been present to watch the first trickle of water creep across the kind of cull of a hill in order to form a new sea. And of course, they would’ve told stories about it.

Tippett: And it speaks to how intelligence is carried forward in time in ways that we don’t necessarily, or that science doesn’t necessarily know how to take seriously, but there it is. That’s knowledge that’s been carried.

Bridle: Yeah. It gets carried forth always in lived tradition in practice. There’s no magic way of transmuting this into another medium that will survive forever. It will end up getting retold and retold over and over again. And it will get changed in that process. And you just see this thing getting handed on and passed down and passed down over time because it can only exist as living practice. There’s no separating it off from the world as we’ve described.

Tippett: I want to return to technology. You mentioned before this way in which the internet, actually, the creation of the internet helped us grasp what is happening in the natural world. You said it was a gift from the technological to the ecological. You write about how “one of the greatest misunderstandings of the 20th century, which persists into the present, was that everything was ultimately a decision problem.” And when computers came along, it was easy to fall into this idea that the universe is like a computer, the brain is like a computer. That we and plants and animals and bugs are like computers. And you’ve also said, “that our contemporary, networked computational technologies might yet be our fullest attempt since the development of language to draw ourselves closer to nature, however carelessly and unconsciously.” So talk me through that.

Bridle: Well, that’s just because of my crazily optimistic belief that we are being constantly brought closer to the world. And in that, I think I’m talking about quite a few things in there. But in one case, I’m particularly talking about AI. AI is an overriding fascination, but I have it with quite a few of these technologies, which they go through this amazing process. I’ve done this before with things like self-driving cars or other new bits of tech where there are things that suddenly in our lifetime are going from, this is what life will be like in the year 3000 to a boring, everyday reality. Just like that, just sort of suddenly. And everyone’s like, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, what? That exists now?”

And this is happening with AI but in this really boring, rubbish way where it’s just stealing everyone’s art and making bad cartoons. But it’s here in some form. But my constant hope is that it can’t just be that. It’s more interesting than that. It has so much cultural weight, and it has so much pull on us. The fact that it, there’s this huge disparity between our fascination with it. Because we have this deep, deep cultural, human fascination with AI and the incredible banality of its reality as put forward by tech companies.

Tippett: It’s reality as opposed to the things that keep getting promised that it will do for us one day.

Bridle: Exactly. Well, not just promised, but what we really imagine. That we imagine something unfortunately mostly like ourselves, but that’s again, just the limits of our own imagination. But we’re imagining something that will shake us to our core fundamentally.

Tippett: Right, right.

Bridle: And we are capable of imagining something that powerful, but what we’re essentially imagining is another intelligence. And that that’s to me, I think is fundamental, is that we’re so bad at imagining non-human intelligence that we have to build this kind of vast mythology because that’s kind of what it is, of AI, of our own creation of some kind of Frankenstein, weird science fiction conglomeration of 20th-century myths in order to imagine that something like other intelligence could exist at all. And then we’re going to put all of our work into this. We’re going to put all of the billions of dollars and we’re going to put all of this press, and we’re going to put all this tech and science into making this thing real because we want it to exist so much. And the end result is that we are going to notice that non-human intelligence exists. That, for me, is the thing that happens at the end of that. That we lose some kind of grip on our solipsism as being the only intelligent things around. And there’s so much strangeness in that desire because it’s somewhat sort of self-obliterating.

Tippett: Yeah.

Bridle: But the fact that we want it so much tells me that we yearn towards not being this incredibly remote…

Tippett: The smartest kids in the room.

Bridle: …That we understand that there’s something wrong with that belief and that it doesn’t match reality. And that’s why something like AI has to exist because there’s something so at odds with our being in the world that we could be so singular and strange. That’s maybe one way of understanding it.

Tippett: It’s just scary to think how much wreckage there might be along that learning path.

Bridle: Well, yeah. History isn’t exactly promising on that regard, is it? Which is why I’m not advocating that path at all. But I would point out that it is the one that we’re on.

Tippett: I want to say that I feel like one of the great puzzles of this century is that we’re faced with these existential, interconnected global challenges, massively complex, that require us to transcend either-or thinking as a matter of survival and actually to grapple with complexity at a species level. And we have landed ourselves on these technological platforms and with technological tools that are based on binary code, which doesn’t make sense.

And you tell really, really amazing stories of all kinds of experimental things that are happening and people coming at this in different ways. I will say that something for me, I am such a believer in that the origins of anything are somewhat deterministic, that they ripple through everything that comes next. And I was so excited in your book to read about that Leibniz, Gottfried Leibniz, this polymath and also a very religious person, had a role in the development of binary numbers. And that for him, rather than this binary being about the ultimate either/or, that the purity of the one and the zero were symbolic of the Christian idea of creation ex nihilo. “Out of nothing, something.” In other words, the one and the zero were symbolic of emergence.

Bridle: Yeah, absolutely. To be clear, a very kind of traditional Christian view of what that emergence meant. But yes, he was contrasting both the materialism of his time, but also the kind of free scientific thinking. So, yeah. Complex, but yes. Yes. It’s more interesting than just ones and zeros.

Tippett: Yeah, exactly. There it is. At least, there’s this little chink of light — that in the DNA of the binary…

Bridle: Well also, you know he got that idea out of the I Ching.

Tippett: …and then he worked with the I Ching, right?

Bridle: Yeah.

Tippett: That’s so fascinating. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Bridle: He was trying to shore up this idea he had of ones and zeros being emblematic of creation ex nihilo, of the kind of power of creation and ultimately of God, and he was looking for examples of it in other ancient traditions so that he could show it came not just out of his own kind of study, but that it was present within the history of humanity more broadly. And he had a friend who was a Jesuit missionary to the 17th-century Chinese court who sent him back some of the first images that I Ching ever seen in the West. Now, this kind of ancient system of divination of course is all based on chance, is all based on the whim of the environment and the world and the universe kind of speaking through this system of numbers. And thus support for his idea of a kind of emergence and ex nihilo creation in binary code.

So all of this non-deterministic, all of this chance, randomness that for me is very much associated with the kind of froth and bubble of the living world lies behind the very cold rationalism of numbers as we understand them today. And again, it’s part of why I sort of insist that despite all appearances and despite all indications of the contrary, technology is constantly trying to draw our attention back to the world because it is part of the world. And it is only us that make that separation and distinction that thinks that high technology, the things that we make are somehow our own creations rather than being part of the vast panoply of becoming, everything being equally evolved, as we said earlier. That computers and satellites and binary numbers are as much part of that ongoing evolution as kind of butterflies and birds, that they’re all kind of springing from the same source unless there’s no meaningful separation between any of them.

[music: “A Palace of Cedar” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: Here’s something else you wrote that felt to me kind of immediately transferrable to how we live. It’s a question again, and you’re talking about understanding the intelligence, the life of “the more-than-human world,” of all that is living around us. You said, “Where we start to move forward is when we learn to ask questions which are less concerned with, ‘Are you like us?’ and more interested in, ‘What is it like to be you?'”

Bridle: Yeah. That’s a reflection on the way in which we’ve always judged non-human beings and indeed, other humans…

Tippett: Other human beings we found ways to distinguish ourselves from.

Bridle: …most of the time. Yeah. And we only value that which is translatable into a quality that we recognize in ourselves. It’s the way we structure things around empathy and identification rather than around practices of solidarity, which recognize the value of other things without having to identify with them as being like us. That’s basically how we’ve always operated, and it has limited our perception and awareness of the vitality of other beings for as long as you have. But other beings have not just have their own ways of doing things, but also have a lot of the answers to questions that we find very difficult to frame of how to live in this world. There’s plenty of answers to this questions, plenty of types of knowledge, plenty of ways of understanding the world, that are held and practiced by non-humans. And for me, I feel very strongly, that the kind of key to our meaningful survival and our flourishing is to be found in learning those lessons and paying attention to them very closely.

Tippett: Yeah. And also, there’s this phrase that you introduce again and again, and there’s this quote by John Muir, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe,” which is what you and I have been talking about. Since his lifetime, we know that in such incredible detail. But as you say, again and again, we share a world. We share a world. And surely, the ultimate thing that we know in our bodies, we must know in our bodies, we know it in our language and places as we’ve talked about. Or somehow strangely, we have to learn, relearn.

Bridle: We have to learn and we have to fight. It’s not just something which we’ve forgotten. It’s something that has been deliberately excluded. And so much of this is the separation that we experience from the rest of the world is deliberate because it benefits others in certain ways. It benefits other forms of power in various ways. And so it’s really important, I think, to remember as well as I say this is a process of kind of reeducation along multiple levels — one of making ourselves more aware, but of also thinking about how we take action and reframe so much of the priorities of our culture around making better worlds.

Tippett: Yeah. I’m curious about your sense of time and what time is and how it works and why it matters, how that might have been affected by all of this work.

Bridle: For a very long time, I think I’ve had this quite a holographic idea of time itself. The experience I describe in the book of doing a little basic time-lapse photography, which I found to be an incredibly powerful technique for just making myself aware of other lives and of the vitality of the world. So what I did was I bought a little cheap time-lapse camera, something that you just basically set up and leave there and it takes photos and made these really terrible low-quality time lapses of plants in my garden and in my living room, but incredibly powerful ones because these were plants I lived with all the time and I knew, but I’d never seen them as clearly as I saw them when this little machine mediated between us and transformed them, translated between their timeframe and mine in this incredibly powerful way.

And it’s a really key point here that’s always worth remaking. It’s just that most of us have seen these kind of time lapses now. They’ve become a bit of a staple of nature documentaries and stuff like this, and that’s great. They’re wonderful, they’re very beautiful, but they do not have the same transformative effect that I’m talking about unless one makes them oneself because it’s one of these things that’s embodied. If you just watch a time-lapse on YouTube, on each documentary, you don’t really know how long it took. The translation doesn’t happen because it still only happens to you for those 30 seconds. When you make it yourself, you have the experience of the actual 24 hours that are compressed into those 30 seconds. Does that make sense? You embody…

Tippett: Yeah. And you’re also sharing life with that thing you’ve been photographing.

Bridle: …you really embody it, and that’s a totally different way of experiencing and understanding the world.

Tippett: And what about consciousness? And that might be connected. How is your understanding of consciousness evolving?

Bridle: Going deeper. Actually, I was quite careful not to talk about consciousness in the book, and I must talk about intelligence, and those are two very different things.

Tippett: Yeah.

Bridle: But I know it makes absolutely no sense to me that you could somehow locate consciousness within a particular physical structure when it is incredibly clear to me that consciousness is something that exists outside the physical universe, that exists completely outside of everything that we perceive physically, and is something that we partake in.

And as Alan Watts says, we come out of the world like waves out of water. We exist as kind of standing waves of a much greater field of energy, the quantum field, as some would describe it. We are just particular incarnations of that, and our consciousness is the bit that still connects us to that underlying field. And for me exists in a completely different plane to things like intelligence and embodiment that are fascinating but are not the same thing.

Tippett: To that point about how we learn, it feels like to me so much that we learn and that we learn collectively and that we’re learning through all the things you and I have been talking about are things that as we’ve been speaking, in many ways, we knew forever if we only knew them in our bodies or we carried them around in words, and that some —

Bridle: That’s what all the philosophical traditions, mystical traditions say, right? You know this already. It’s just a process of remembering.

Tippett: Yeah. And that we know things, and then what feels like the learning is we know them for the first time with consciousness. But I think that thinking about what you just said about that doesn’t mean that it’s not necessarily a light going off inside us, that it’s us partaking in something. Here is a line of yours. “Every time we train our most sophisticated tools upon the central questions of our existence – Who are we? Where do we come from? Where are we going? – the answer comes back clearer: Everyone and Everywhere.”

Bridle: It’s good, isn’t it? I don’t mean that about my writing, but that realization, to me, it’s just so clear, that that is what everything is constantly yelling at us if we choose to pay attention if we choose to hear it.

Tippett: Just as we finish, how would you start now, having steeped in all of this and kind of living these questions that you live, how would you start to answer this vast question of what it means to be human? Perhaps, how has that evolved how you might start to answer that question?

Bridle: What it is to be human is such a small thing…

Tippett: I know.

Bridle: …in this universe, right? Just try to be nice, be kind babies, be kind. As Vonnegut wrote. That’s the only guide. Try to be good and try to do the least harm and be kind. That’s the only human bit. But what it means to be more-than-human, that’s something else. That’s the bigger question, I think, for me is what it means to transcend that narrow frequency of being human in this time here to perhaps partake of something far greater, something more-than-human. That is actually the more deep or meaningful connection to everything around us.

[music: “Eventide” by Gautam Srikishan]

Tippett: James Bridle’s books are Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence — and before that, New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future. Their writing has appeared in The Guardian, Wired, The Atlantic, and many other places. Their art has been exhibited around the world, including recently at NOME Gallery in Berlin.

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Gautam Srikishan, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Amy Chatelaine, Romy Nehme, Cameron Mussar, Kayla Edwards, Juliana Lewis, and Tiffany Champion.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. We are located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. Our closing music was composed by Gautam Srikishan. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

Our funding partners include:

The Hearthland Foundation. Helping to build a more just, equitable and connected America — one creative act at a time.

The Fetzer Institute, supporting a movement of organizations applying spiritual solutions to society’s toughest problems. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation. Dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.