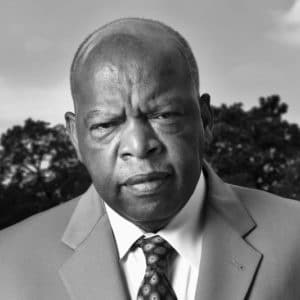

John Lewis

Love in Action

An extraordinary conversation with the late congressman John Lewis, taped in Montgomery, Alabama, during a pilgrimage 50 years after the March on Washington. It offers a special look inside his wisdom, the civil rights leaders’ spiritual confrontation within themselves, and the intricate art of nonviolence as “love in action.”

Image by Trent Gilliss, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

John Lewis was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Georgia’s 5th Congressional District. He was the author of Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement, Across That Bridge: Life Lessons and a Vision for Change, and March, a three-part graphic novel series. He died on July 17, 2020.

Transcript

July 22, 2020

Rep. John Lewis: When we were sitting in, it was love in action. When we went on the freedom ride, it was love in action. The march from Selma to Montgomery was love in action. We do it not simply because it’s the right thing to do, but it’s love in action. That we love our country, we love a democratic society, and so we have to move our feet.

[music: “Precious Lord/Oh Freedom” by Betty Mae Fikes and the Congressional Delegation]

Krista Tippett, host: Spending time with John Lewis, who died last week, was one of the great experiences of my life. He was a United States congressman, and a core leader — one of the “Big Six” — of the civil rights movement. He led the first Selma march on what became known as Bloody Sunday. I had the honor to take part in a civil rights pilgrimage led by this man and attended by 30 members of the House and Senate from both parties. We stood on holy ground of the movement in Tuscaloosa, Birmingham, Montgomery, Selma. It was a journey into history I thought I knew, but didn’t really — into the civil rights leaders’ spiritual confrontation within themselves — and into their intricate art and work of successful nonviolence.

This is Betty Mae Fikes, leading song on the pilgrimage — a half-century after she was a teenaged freedom singer of the civil rights movement.

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett. This is On Being.

[music: “Precious Lord/Oh Freedom” by Betty Mae Fikes and the Congressional Delegation]

Tippett: I spoke with congressman John Lewis in Montgomery, Alabama in 2013.

Tippett: I’d like to start by talking about faith, which is a bedrock of your life. It’s one of the bedrocks that you name prominently in your most recent book. And I’d like to just hear a little bit about how you would describe the foundation of faith, the spiritual background of your childhood.

Lewis: I grew up in rural Alabama about 50 miles from Montgomery outside of a little place called Troy. My father was a sharecropper, a tenant farmer. But back in 1944, when I was four years old — and I do remember when I was four — my father had saved $300 and, with the $300, he bought a 110 acres of land.

We grew up very, very poor — six brothers, three sisters, wonderful mother, wonderful father, wonderful grandparents. But growing up as a child, I saw segregation and racial discrimination, and I didn’t like it. And I would ask my mother and my father, my grandparents, my great-grandparents, why. They would say, “That’s the way it is. Don’t get in the way. Don’t get in trouble.”

But attending church and Sunday school, reading the Bible, the teaching of the great teacher, and being deeply influenced by what I saw all around me, it was this belief that somehow and some way things were going to get better, that you have this sense of hope, a sense of optimism and have faith. And people would say to me, my mother would say over and over again, “Work hard.”

And sometime working in the field, I would say to my mother, “This is hard work, and this work is about to kill me.” And she would say, “Boy, hard work never killed anybody.” So I worked very, very hard as a child. But one day in 1955, at the age of 15, I heard of Rosa Parks. I heard the words of Martin Luther King Jr. on the old radio, and he was talking and preaching about nonviolence, about peace, about reconciliation, about the capacity, the ability, to change things, and …

Tippett: And he was a preacher.

Lewis: He was a preacher, and I wanted to be a preacher as a young child. And I had this sense that, if I believed, if I had faith in my own capacity and ability to get things done, I too could change things. So I just never gave up and never gave in. I just tried to hold on. So when I went away at the age of 17 …

Tippett: Wait. I want to stay with 14 and 15 just for a minute because I’ve read both of your books these last few days. I actually have a 14-year-old son who’s here with me on this pilgrimage, and it was so striking to read about you being 14 in 1954 and reading about Brown v. Board of Education. And also as I read it, being filled with hope and excitement at that news and also not seeing anything change immediately in the world of Alabama.

And really those years of you were 14 and heading into 15, as you say, in 1955 you heard Martin Luther King’s voice for the first time, the bus boycott, and also things like another 14-year-old boy, Emmett Till, who was killed in Mississippi. So talk a little bit about how that period in your life, which in any life is a tumultuous moment, what started to happen to you then?

Lewis: During that period, I raised a lot of questions and I asked a lot of questions of my mother, my father, other ministers around. They accused me of being nosy, and I thought of myself as just wanting to know. I was inquisitive.

When I heard about the Supreme Court decision in 1954, I thought the next school year that I would go to a better school. At least it would be a desegregated school. I wouldn’t have to ride a broken-down bus and I would be able to get new books, but it never happened for me. It never happened, but I didn’t give up. I didn’t become bitter or hostile. I kept the faith and I remembered hearing about what happened to Emmett Till, and I thought, if something like this can happen to a young man, young boy …

Tippett: This is a young man who was visiting relatives in Mississippi from Chicago, right?

Lewis: Yes, and it could happen to any of us. And I remember even before then in 1951, when I was 11 years old, I traveled one summer with an uncle and aunt and some of my first cousins from rural Alabama to Buffalo for a visit, for a trip. I had never been outside of the South. And being there gave me hope. And I saw how people lived there — the way they’re living in Buffalo. Maybe somehow and some way, we can make the South, make a region.

I wanted to believe, and I did believe, that things would get better. But later I discovered, I guess, that you have to have this sense of faith that what you’re moving toward is already done. It’s already happened.

Tippett: Say some more about that.

Lewis: It’s the power to believe that you can see, that you visualize, that sense of community, that sense of family, that sense of one house.

Tippett: And live as if?

Lewis: And you live that you’re already there, that you’re already in that community, part of that sense of one family, one house. If you visualize it, if you can even have faith that it’s there, for you it is already there. And during the early days of the movement, I believed that the only true and real integration for that sense of the beloved community existed within the movement itself.

Because in the final analysis, we did become a circle of trust, a band of brothers and sisters. So it didn’t matter whether we’re Black or white. It didn’t matter whether you came from the North, to the South, or whether you’re a Northerner or Southerner. We were one.

Tippett: You had made that vision real.

Lewis: For the struggle, for those of us in the struggle. But we studied. We prepared ourselves.

Tippett: Well, this is something else I want to talk about: the study, the preparation, the discipline? I think the term nonviolent resistance in the 21st century is a term everyone has heard, but reading about how you practiced that, how you learned it. I mean, there were small things like maintaining eye contact, you know, wearing coats and ties and dresses, no slouching, no talking, being friendly and courteous. But there was also really serious role-playing.

You made a comment. We are meeting each other in the context of a pilgrimage, retracing many places in the civil rights movement with members of Congress and others, which you’ve helped begin, which is an incredible thing.

Yesterday in one of these meetings, you made a comment which was humorous and serious at once, I think, that it would be good for Congress to take up some of the kind of role-playing that you did in the 1950s, 1960s, in the civil rights movement. So would you tell us a little bit about that, what you all did to prepare possibly to be beaten, to be imprisoned, possibly to be killed?

Lewis: Well, long before any sit-in, any march, long before the freedom rides, or the march from Selma to Montgomery, any organized campaign that took place, we did study. I remember as a student in Nashville, Tennessee, a small group of students every Tuesday night at 6:30 p.m. would gather in a small Methodist church near Fisk University in downtown Nashville.

And we had a teacher by the name of Jim Lawson, a young man who taught us the philosophy and the discipline of nonviolence. We studied. We studied what Gandhi attempted to do in South Africa, what he accomplished in India. We studied Thoreau and civil disobedience. We studied the great religions of the world. And before we even discussed a possibility of a sit-in, we had role-playing. We had what we called social drama.

Tippett: OK.

Lewis: And we would act out. There would be Black and white young people, students, interracial group, playing the roles of African Americans, or be an interracial group playing the roles of white. And we went through the motion of someone harassing you, calling you out of your name, pulling you out of your seat, pulling your chair from under you, someone kicking you or pretending to spit on you. Sometimes we did pour cold water on someone, never hot — but we went through the motion.

This was drama because we wanted to feel like they were in the actual situation, that this could happen. And we would tell people, whether young men or young women, that if you’ve been beaten, try to protect the most sensitive part of your body. Roll up, cover your head and look out for each other. So when the time came, we were ready. We were prepared.

Tippett: I also read somewhere that you were trained even if someone was attacking you to look them in the eye, that there was something disarming for human beings.

Lewis: We did go through the motion, the drama, of saying that if someone kick you, spit on you, pull you off the lunch counter stool, continue to make eye contact. Continue to give the impression, yes, you may beat me, but I’m human.

Be friendly, try to smile, and just stay nonviolent. And during the nonviolent campaign in a city like Nashville and so many other parts of the American South, you never had one incident of someone striking back or hitting back. There were even people who would say, “I cannot go on the sit-ins. I cannot go on the freedom ride. I may not be disciplined enough.” But we were trained. When we left to go on the freedom ride, we were prepared to die for what we believed in.

Tippett: In the way I come to understand this as I, again, study you is the point of all of this role-playing was not just about being practically prepared. You know, I suspect that some neuroscientist now in the 21st century probably understands what happens in our brain somehow with what you knew about that moment of eye contact and human connection. But you also understood this to be a spiritual confrontation first within yourselves and then with the world outside. Is that right?

Lewis: You’re so right. First of all, you have to grow. It’s just not something that is natural. You have to be taught the way of peace, the way of love, the way of nonviolence. And in the religious sense, in the moral sense, you can say in the bosom of every human being, there is a spark of the divine. So you don’t have a right as a human to abuse that spark of the divine in your fellow human being.

We, from time to time, would discuss if you see someone attacking you, beating you, spitting on you, you have to think of that person, you know, years ago that person was an innocent child, innocent little baby. And so what happened? Something go wrong? Did the environment? Did someone teach that person to hate, to abuse others? So you try to appeal to the goodness of every human being and you don’t give up. You never give up on anyone.

[music: “Care” by Keith Kenniff]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today remembering congressman and civil rights legend John Lewis, who died last week. On March 7, 1965, John Lewis led a peaceful march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma — and was one of the first to be beaten unconscious by police. That day became infamous as Bloody Sunday.

Tippett: So here’s a line from your book Across That Bridge: “The civil rights movement, above all, was a work of love. Yet even 50 years later, it is rare to find anyone who would use the word love to describe what we did.” What you just said to me illuminates that. I think part of the explanation of that is the way you are using the word love is very rich and multilayered and also challenging, challenging for the person who loves.

Lewis: Well, I think in our culture, I think sometimes people are afraid to say I love you. But we’re afraid to say, especially in public life, many elected officials or worldly elected officials, are afraid to talk about love. Maybe people tend to think something is so emotional about it. Maybe it’s a sign of weakness. And we’re not supposed to cry. We’re supposed to be strong, but love is strong. Love is powerful.

The movement created what I like to call a nonviolent revolution. It was love at its best. It’s one of the highest form of love. That you beat me, you arrest me, you take me to jail, you almost kill me, but in spite of that, I’m going to still love you. I know Dr. King used to joke sometime and say things like, “Just love the hell outta everybody. Just love ’em.”

Tippett: Love the hell out of them, right, yeah [laughs]. Gandhi was such an important figure for you, for all of you, for Dr. King as well. I also think that may be a little bit lost in our collective memory. I think it’s important to remember that, the very rich spiritual lineage that you were all drawing on and became part of. I was really struck by you. You often refer to one of Gandhi’s important terms, satyagraha.

You know, again, in terms of breaking open this word love out of the kind of superficial ways we talk about it or nonviolence in a superficial way, the definition of that that you give is steadfastness in truth, active pacifism, right? Revolutionary love is another way to think about that. Not just an external stance, but a fundamental shift inside our own souls. It’s very powerful. It’s not the way — certainly not the way I hear people talking about public life or political action, now.

Lewis: I think all of us in life, not just in the Western world, but all over the world, we need to come to that point. We need to evolve to that plane, to that level where we’re not ashamed to say to someone, “I love you, I’m sorry, Pardon me, Will you please forgive me? Excuse me.” What is it? Have we lost something? Can we be just human and say I love you? I think so — so many occasions we think of love as being romantic and all of that, but just love because it’s good in itself, just love living creatures.

Now, when I was very young, you probably know that I fell in love with raising chickens, and I loved those chickens. I talked to those chickens. I preached to those chickens and I used to cry when my mother or father wanted to kill one of those chickens for dinner. They became part of my life, and my first nonviolent protests were protesting against my parents for getting rid of some of those chickens.

Tippett: OK [laughs]. Let’s talk a little bit about suffering, which is something that went right alongside that love in the movement, even with your chickens and I think in the way you live now. You use the term redemptive suffering and that your mother, who was clearly a woman of incredible dignity and grace and courage, really internalized the idea of unearned suffering as a holy thing, that she would redeem that suffering.

You also wrote: “Suffering can be nothing more than a sad and sorry thing without the presence on the part of the sufferer of a graceful heart, an accepting, an open heart, a heart that holds no malice toward the inflictors of his or her suffering.” I mean, I guess that brings us back to this idea of love.

But, you know, I want to ask you, before the triumphant Montgomery-Selma march that we’ve all seen, the beautiful pictures of King and Heschel and all those other people walking across the bridge, there was Bloody Sunday and you were in the front rows of that and you were the first person to be hit. That was an incredibly brutal act. Were you able on that bridge, as you were knocked — as you were given a concussion, as other people were very badly injured, to really internalize that accepting an open heart? Do you know that that’s possible?

Lewis: I was prepared to accept the violence, the beating. And I thought we were going to be arrested and simply taken to jail. I didn’t have any idea that we would be beaten.

Tippett: And that you would be met by these masses of officers, horses …

Lewis: State troopers and horses and a posse of the sheriff, that we would be trampled by horses and tear-gassed and beaten all the way back to the church. I thought I was going to die. I thought I saw death. I thought it was my last nonviolent protest. But before, I guess, I lost consciousness, I became deeply concerned about the other people on the march. But in all of the years since, I’ve not had any sense of bitterness or ill feeling toward any of the people. I just don’t have it. I guess it’s not part of my DNA to become bitter, to become hostile.

Tippett: But you’ve also trained your DNA a bit more than the rest of us [laughs].

Lewis: Well, maybe I tracked it. Yeah, I did control it. But the teaching, the training, the reading, and coming in contact with great teachers. Martin Luther King Jr. had a tremendous influence on me and the reading and the study of Gandhi.

When I saw the film several years ago of Gandhi and saw the march to the sea, it reminded me of the march from Selma to Montgomery. That there come a time where you have to be prepared to literally put your physical body in the way to go against something that is evil, unjust, and you prepare to suffer the consequences.

But whatever you do, whatever your response is, is with love, kindness, and that sense of faith. In my religious tradition is this belief that it’s going to work out. It is going to work out. It’s all going to be all right. And people will ask me from time to time, “What shall we do, John, during the sit-ins or during the freedom rides?” And I would say, “We need to find a way to dramatize the issue. We need to find a way to get in the way, but it should be in a peaceful, loving, nonviolent fashion.” Hate is too heavy a burden to bear.

Tippett: And do you feel like even in that moment on that dark day on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, were you able to love those officers who came at you in this sense you’re describing?

Lewis: I saw these officers as individuals carrying out an order. And since then, I’ve had an opportunity to meet some of their sons and daughters of some of the people. I had a discussion on one occasion with Governor Wallace about what happened on that Sunday.

Tippett: And Governor Wallace would have ordered them or he would have been behind that.

Lewis: Well, he was the governor. He wanted the march stopped. He said he never gave them the order to beat us. He said to me, “John, there were people waiting on the other side of the bridge to kill you.” And I said, “Governor, when we were stopped, it appeared to me there was an attempt to kill us before other people killed us.”

Tippett: Right.

Lewis: He said it was a struggle between the federal government and the state government and not against us.

Tippett: On this — sorry.

Lewis: But I never had any bitterness toward him or any of the officials, even going back to the freedom rides when we arrived in Montgomery in 1961.

There was a man named Floyd Mann who was a public safety director of the Alabama State Troopers. He came and stood and put a gun up in the air and said something like, “There will be no killing here today. There’ll be no killing here today.” And several years later, I saw Floyd Mann after I got elected to Congress at the dedication of the Civil Rights Memorial. And he asked me, he said, “Congressman Lewis, do you remember me?” And I said, “Mr. Mann, how could I forget you? You saved my life.” He cried and I cried.

[music: “Precious Lord” by Congregation at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church]

Tippett: This is the choir from the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church where Martin Luther King Jr. pastored and preached during the 381-day Montgomery bus boycott. And they led this Congressional delegation with John Lewis in singing King’s favorite hymn.

[music: “Precious Lord” by Congregation at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church]

Tippett: After a short break, more with the late John Lewis. You can hear the whole unedited conversation I had with him in Montgomery, or just listen again, on the On Being podcast feed — wherever podcasts are found.

[music: “I Am Healed” by Moses Tyson Jr.]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today we’re remembering civil rights legend, congressman John Lewis, who died last week. I interviewed him in the midst of a civil rights pilgrimage in 2013 through his native state of Alabama. A delegation of over 200 people attended including the Republican House Majority Leader, the daughters of Lyndon Johnson and George Wallace, and civil rights luminaries like Ruby Bridges, who was the first African American girl to desegregate an all-white southern school.

Tippett: I was present and very privileged just today here in Montgomery to witness the head of public safety here in Montgomery, the chief of police, offer you a public apology and a new generation of Montgomery policemen talk about his work to bring the truth of that history to policemen coming up now. It was an incredible moment.

Lewis: It was a very moving moment to me. You know, I cry sometimes and sometimes I think I cry too much, but they’re tears of gratitude, tears of appreciation, joy, happiness, of seeing something about the distance we’ve come and the progress we’ve made. What the chief did today was so meaningful.

Tippett: He gave you his badge too.

Lewis: You know, I said to him, I’m not worthy. I wanted to say to him, you don’t have to do this, but he did it. It says something about the power of love, the power of nonviolence that it happened to move us toward a reconciliation.

Tippett: And I keep wanting — I want to push you a little bit because the word love, as you said, you know, it’s romantic. Love as you are talking about it, as you have aspired to live it, is not a way you feel. It’s a way of being, right?

Lewis: It’s a way of being, yes. It’s a way of action. It’s not necessarily passive. It has the capacity. It has the ability to bring peace out of conflict. It has the capacity to stir up things in order to make things right. When we were sitting in, it was love in action.

Tippett: When you were doing the sit-ins like at lunch counters, at big department stores that had been segregated?

Lewis: Right. When we went on the freedom ride, it was love in action. The march from Selma to Montgomery was love in action. We do it not simply because it’s the right thing to do, but it’s love in action. That we love our country, we love a democratic society, and so we have to move our feet.

Tippett: That phrase, an African proverb, when you pray, move your feet. You’ve got that in both of your books. I even tweeted it the other day. People love it. It’s an amazing phrase. It’s also interesting how that imagery recurs. You talk about Montgomery and speaking with their feet, you know, Heschel after the march said he felt like he was praying, his feet were praying. I wonder if you think about, you became a congressman, is it right, in 1987? Is that right?

Lewis: I took office in 1987, elected in ’86.

Tippett: OK. So is being in politics part of your way of praying with your feet now?

Lewis: I see my involvement in American politics as an extension of my faith, not simply as an extension of my involvement in the civil rights movement. My life, whether in the civil rights movement or whether in American politics, is an extension of my faith. It’s the sense that you believe that somehow and some way with love and a sense of I got to do it. You know, I talk about the spirit and I talk about the spirit of history.

Tippett: Yes, you do.

Lewis: And sometimes it’s this feeling that you have been tracked down, as Dr. King would say.

Tippett: You’ve been what?

Lewis: You have been caught up. You have been led. You have been not necessarily forced, but something caught up with you and said, “John Lewis, you too can do something, you too can make a contribution, you too can get in the way, but if you’re going to do it, do it full and with love, peace, nonviolence, and that element of faith.”

Tippett: I wonder if you have the distinction of being the U.S. congressman who spent the most days in jail in his life [laughs].

Lewis: I don’t know. I never thought about it. I’ve not thought about it.

Tippett: I can’t believe there could be many who’ve been in jail more than 40 times.

Lewis: Well, I didn’t want to go to jail.

Tippett: I know [laughs].

Lewis: Jail is not a pleasant place, but jail became one of the ways out. To be arrested, to go to jail when it’s unearned suffering, it sent a message. It helped make the person who’s suffering better. I felt so good the day I was arrested.

Tippett: But, again, that internal discipline was at play, right?

Lewis: Yes.

Tippett: You were turning that unearned suffering into something.

Lewis: Well, we were using it to help move the society, but also not just the larger society, but to help move us as individuals, that you can suffer and you can come out better. I felt liberated. I felt free.

Tippett: Something else I want to talk to you about is the idea of patience. Someone might look at your life and thinking and the civil rights movement and say there’s always this tension between a commitment to nonviolence and a total resistance to and struggle with injustice. I want you to help us inside this virtue of patience as you’ve learned it and lived it. You know, there are places in your memoir that are just so striking to me.

Here’s a line, you were talking, I think, about literacy training, voting rights and all the things you’ve trained people in, and you said, “We perceived that waiting was an elegant way to prove a point.” You know, that again and again, in these different situations that the civil rights fighters put themselves into, your civility demonstrated the absurdity of the other side. So there’s a patience there, but there’s also a total impatience.

And at the March on Washington, your speech that you were going to give was actually edited and there was lots of hand-wringing, and here’s what you had planned to say: “We will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own ‘scorched earth’ policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground — nonviolently. We shall fragment the South into a thousand pieces and put them back together in the image of democracy.” So how — help us understand how that is not a contradiction to the virtue of patience.

Lewis: Also in the speech near the beginning, I say, “You tell us to wait.” You’re right. You’re right. You got it right. I say, “You tell us to wait. You tell us to be patient. We cannot be patient. We want our freedom and we want it now.” So when you look at that speech of August 28, 1963, you’re seeing a speech by a young guy 23 years old. I learned. I’ve become better. I’m wiser. You can say all of that.

Tippett: Mm-hmm.

Lewis: But at the same time, I would tell my members of my own family and members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and members within the movement, within S.N.C.C and S.C.L.C and others, I’ve always said, “Pace yourself, pace yourself.” I would tell my wife and say, “Every fight is not your fight. Pace yourself.” And I would say it to the young people and others sometime, “Don’t get in a hurry. Our struggle is not a struggle that lasts for one day, one week, one month or one year or one lifetime. It is an ongoing struggle.”

Tippett: So, patience — right, yeah.

Lewis: And in the speech of the March on Washington, I had a lot of rhetoric and, in the end, I knew within my own soul that it was going to be a long haul and I believe that. But you don’t change the world, the society, in a few days, and it’s better. It is better to be a pilot light than to be a firecracker [laughs].

Tippett: Right.

Lewis: Because if you’re a pilot light, you’re going to be around. A firecracker coming along in you, just go off. You’re here one moment and you’re gone in the next moment.

[music: “Po’ Pilgrim of Sorrow” by James Horner & Sweet Honey in the Rock]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today remembering congressman and civil rights legend John Lewis who died last week. I had the great honor of speaking with him in Montgomery, Alabama in 2013 — as part of a cross-partisan congressional civil rights pilgrimage which he led for many years.

Tippett: Do you hear me? Although it’s a creative tension here, it’s a line you’re walking.

Lewis: Yes.

Tippett: And it sounds like when I read the history of the movement, you and others walk back and forth across that line all the time. But it was that keeping, as you say, the pacing, the somehow always being able to pull back and see the long haul, I suppose. It’s that stance, it’s that attitude.

Lewis: But we wanted to end discrimination now. We wanted people to be able to register and vote now. And we had a slogan called “Freedom Now.” But to hand a sort of revolutionary effect, it was going to take much longer when you’re able to change the minds and hearts and souls of people.

Tippett: How do those experiences, those values that you learned, flow into your life in politics in our time?

Lewis: Well, I think today I’m a much better person and much better human being. Sometime when I’m sitting on the floor of the House or in a committee meeting, I feel like sometime saying, you know, I passed this way once before. You know, if I was back in Nashville or in Georgia on a protest or maybe on the freedom ride, what would we do? What would Martin Luther King Jr. say? What would Gandhi do? So you cannot give up on certain basic principles and basic teachings.

Tippett: I don’t think anybody would accuse the Congress right now of being a beloved community.

Lewis: Well, I think we have some distance away from becoming the beloved community, but I will not give up on Congress. And it’s my hope that, when members of Congress come on trips and journey and a pilgrimage, that they will learn something, that it will grow and will become better members and better human beings.

Tippett: You know, some of the radical aspects of this nonviolence tradition that you were steeped in, that you now bring to your life as a congressman — here’s something I read in your book, that after the firebombing of the Birmingham church in which four little girls were killed, where I was privileged to be with you this weekend, Reverend King said, “At times, life is hard, as hard as crucible steel. … In spite of the darkness of this hour, we must not lose faith in our white brothers.” You know, that very demanding notion not just of having faith in yourself or faith in your movement, but faith in your enemies.

Lewis: You have to believe and you can never, ever, give up on any possibility. It’s part of it, as I said, from the beginning. It’s already done. You just have to find a way to make it real.

Tippett: I remember when you write about being a student and being exposed to the world of philosophy and theology and reading about the notion of the dialectic and thinking about segregation as a thesis and the fight against desegregation as the antithesis and integration as the synthesis, the end. I wonder how you see that now, because does the dialectic start all over and what …

Lewis: Well, I don’t think it necessary to start all over again. But I had a wonderful teacher when I was at American Baptist College. His name was John Lewis Powell, and he would start discussing this idea of the thesis and the antithesis and the synthesis, and he would run around the blackboard writing and jumping.

That’s what the struggle has been all about, to bring these competing forces together, bring human beings together, and create a sense of community, to create this sense of family, that out of the good — the good is already there. The love is there. How do you make it real? How do you paint the picture? It’s like an artist using a canvas. How do you get people to move from maybe A to B and you get C? Or from one to two and get three? That you’re on a path and you have to be consistent and you have to be persistent.

Tippett: And patient.

Lewis: And patient.

Tippett: Right.

Lewis: And it’s all about being faithful, being honest, being open.

Tippett: It’s so clear with every accomplishment of humanity and certainly with the civil rights movement that so much important change, good change, happened and yet there’s still much more work to do. Unforeseen complications appear, setbacks appear, that even all the best things we do remain imperfect and incomplete. How do you think about that and about where the movement is in terms of your faith?

Lewis: Well, I think about it, but you have to believe there may be setbacks, there may be some disappointments, there may be some interruption. But, again, you have to take the long, hard look. With this belief, it’s going to be OK; it’s going to work out. If it failed to happen during your lifetime, then maybe, not maybe, but it would happen in somebody’s lifetime. But you must do all that you can do while you occupy this space during your time. And sometimes I feel that I’m not doing enough to try to inspire another generation of people to find a way to get in the way, to make trouble, good trouble. I just make a little noise.

Tippett: I think you embody the things that you speak and that we watch you as much as hear you. You move your feet [laughs]. So, John Lewis, I want to thank you so much for the life you’ve lived and for this conversation we’ve been able to have with you this afternoon.

Lewis: Well, thank you very much. I enjoyed it. Thank you.

[music: “I’m Gonna Live the Life I Sing About” by R.L. Knowles]

Tippett: John Lewis died in Atlanta, Georgia on July 17, 2020, at the age of 80. He was a Democratic congressman from Georgia’s 5th district. He was the author of several tremendous books, Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement, Across That Bridge, and a three-part graphic novel series, March.

[music: “I’m Gonna Live the Life I Sing About” by R.L. Knowles]

Tippett: Special thanks this week to Brenda Jones in congressman Lewis’s office; Gwen Haynes; Jeremy Burns; Burns Strider; and Liz McClosky, Doug Tanner and all the other great people at the Faith and Politics Institute.

[music: “new music” by Mavis Staples]

The On Being Project is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Laurén Dørdal, Erin Colasacco, Kristin Lin, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Serri Graslie, Colleen Scheck, Christiane Wartell, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, and Jhaleh Akhavan

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation. Dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.