Kate DiCamillo

On Nurturing Capacious Hearts

In her writing, it is Kate DiCamillo’s gift to make bearable the fact that joy and sorrow live so close, side by side, in life as it is (if not as we wish it to be). In this conversation, along with good measures of raucous laughter and a few tears, Kate summons us to hearts “capacious enough to contain the complexities and mysteries of ourselves and each other” — qualities these years in the life of the world call forth from all of us, young and old, with ever greater poignancy and vigor.

Image by Vicki Ling, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Kate DiCamillo has written many bestselling books, beloved by children and adults in touch with their inner eight-year-old, for two decades, including Because of Winn-Dixie, The Tale of Despereaux, The Magician’s Elephant, Flora & Ulysses, and The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane. Some of these have been turned into operas and movies. Her new books in 2024 include the middle grade novel Ferris and Orris and Timble: The Beginning. She is a rare two-time winner of the Newbery Medal.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

Krista Tippett: Each and every one of us is a former eight-year-old — wide open with yearning and possibility; almost unbearably alert to the world’s wonders and its dangers all at once; understanding exactly how troubled the adults around you are, even if they think they are hiding it from you. In her writing, it is Kate DiCamillo’s gift to make bearable the fact that joy and sorrow live so close, side by side, in life as it is — if not as we wish it to be. In this conversation, along with good measures of raucous laughter and a few tears, Kate summons us to hearts, as she’s said, “capacious enough to contain the complexities and mysteries of ourselves and each other.” And it seems to me that these years in the life of the world call that forth from all of us, young and old, with ever greater poignancy and vigor.

Kate DiCamillo has near cult status among teachers and parents and young former children who’ve grown up reading her books, which include The Tale of Despereaux; The Magician’s Elephant, The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane, and Flora & Ulysses. I read her books with my children and in recent years I’ve read them by myself. But you don’t have to have read any of them to drop into this conversation and gather refreshment for life in this world.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Because of Winn-Dixie, about a girl and her dog, was Kate DiCamillo’s first novel, published in the year 2000. She is a rare two-time winner of the Newbery Medal. And I interviewed her from the makeshift pandemic recording studio in my basement — while she was sitting in my seat in the On Being recording studio in Minneapolis.

Tippett: Hello. [laughter] Do you want this to be a recordable hello, or is this for levels?

Kate DiCamillo: [laughs] That was the most uncertain hello I’ve ever heard in my life.

Tippett: Hello, Kate. Hello, Kate. Welcome.

DiCamillo: Hello, hello, Krista. Thank you for the great gift of talking with me. I’ve been looking forward to it.

Tippett: So I think one thing that feels like a challenge, but a challenge I’m very happy to walk into, is I haven’t interviewed many writers of fiction, across the years. It’s tricky, because I really want to talk to you as this person who has brought all these characters and stories and worlds to many others, but that somebody could enter this conversation that we’re going to have without having read any of it, and not feel like they’re missing something because they haven’t read anything. Does that make sense?

DiCamillo: Yeah, and I can see what a challenge it is. You’re right.

Tippett: Just to start, it occurred to me, as I actually learned more about your life story, if this were a story about you [laughs] that Kate DiCamillo wrote, it would begin with a sickly child named Kate.

DiCamillo: Yup. Yeah. I’m already — I’m still stuck back on there, on “if this were a story that I wrote,” which is — it’s kind of got a — it’s got a rabbit-hole quality to it, if I fall into that kind of thinking. But okay, I’m with you. So yes, a sickly child.

Tippett: Well, it sounds like you just — someplace, you said or wrote, “My body happily played host to all of the usual childhood maladies (mumps and measles, chicken pox … ear infections), plus a few exotic extras: inexplicable skin diseases, chronic pinkeye” — and then you had recurring pneumonia, every winter, for the first five years of your life.

DiCamillo: Right, right. I mean, it just makes me sound [laughs] so pathetic. And, I think so much, when you say all that, I think — I mean, I feel it. And I also, I think, how did that kid survive? And then I know exactly what the answer is. She laughed, and she read…

Tippett: [laughs] And she read.

DiCamillo: …and she made friends. Those would’ve been the saving graces. And, you know, it also — all of those things turned out to be peculiar gifts, in a way, because the pneumonia got us to Florida from Philadelphia. That was, as I say to the kids, in a time long, long ago, when “geographical cures” were still prescribed, and —

Tippett: So the doctor said that the family would take you to Florida, and that would be good for your pneumonia. Was it? Did it actually cure your pneumonia?

DiCamillo: Yeah, I didn’t get any pneumonia anymore, but I got everything else. And it’s — see, this is the trick of you, Krista, is, already — and it’s not through having sat around a table with you, it’s just, it’s your gift — is that I’m going to say more than I would normally say. So here I go. I’m just going to say it, and you can edit it out if you think it’s — but it was a gift because it got us to Florida and away from my father, which, at the time, as a kid, I didn’t perceive as a gift. Instead, I was just like, where is he? And is he going to come back? And — but we all would’ve, as my mother often said, ended up in a mental institution if he had stayed. So it was good. And also, it was good because I came from Philadelphia to Florida, and I felt like Alice in Wonderland. It’s like, there were — there was Weeki Wachee, where there are underwater mermaids. There was Gatorland, where you walked through a cement jaw of an alligator and watched the Gator Jumparoo. And it was the South. People told stories. And I just — I was raised by that small town, basically.

Tippett: What you just shared about getting away from your father, I haven’t seen you share that anywhere, so, I mean, thank you for that. I also know that that’s something you see in hindsight, and as a — were you five, six?

DiCamillo: I was five, and then I turned six down there, and yeah, and it wasn’t — it’s also that thing — and this is something I don’t talk about a lot, either — the conceit around the whole move was, We’re moving because Kate needs to be in a warm climate. And my father was an orthodontist, and he was going to sell the practice, and then after that was all taken care of, he was going to move to Florida. And that didn’t happen. And it’s not that I didn’t see him; he showed up and did many wonderful things — paid for my education, contributed to me loving words and stories. But I knew that the — I remember sitting on the back steps of Idabell Collins’s house — she was the next-door neighbor — and she’s like, Now, when is your — when’s your father going to get here? And I said, Soon; he’s going to get here soon. And I remember thinking, I know that’s not true. But you lie for the adults, kind of.

Tippett: Right. Right.

DiCamillo: We’re off to the races, here.

Tippett: We are. We are, and we’re going to come back to that, probably. Kate, there’s a lot of magic in your books. And I’m sort of going to speak about — it’s not just magic. It’s magic and it’s a real clear-eyed realism about how complicated and often difficult and often impossible and devastating life can be. And I read, I experienced your body of work with and through my children, particularly my daughter, who I’m probably going to quote. She’s my at-home Kate DiCamillo expert, [laughter] and I almost thought that she should do this interview. So I read all the books kind of with her, or watched them be part of her life, especially after she left the books that you wrote, when she was at different stages in her life.

And I realized that as I’m sitting with you now, in — let me just — I’m not going to call — it’s not a post-pandemic world, but let’s say the post-2020 world, where a lot of things are never going to go back to what we thought they were, or the future doesn’t look the way we thought it would look — children and adults are reading your books in a world that has become unmoored, that school and play have become unmoored, that parents have become unmoored.

So I kept thinking — as I was reading you again and thinking about this — of a conversation I had, early, early in the years of the show, with the great child psychiatrist Robert Coles. Did you ever read him? He wrote The Spiritual Lives of Children, but he also wrote about the political lives of children and the moral lives of children. And he actually started his career as a child psychiatrist, watching Ruby Bridges walk into that schoolhouse every day, month after month, being heckled and yelled at by adults, and being alone in that school. So he was attentive and so articulate about the fact that children know everything about how hard the world is. And there’s this impulse we have, certainly as parents, to shield them, and that they know everything, right? They see that people die. They see that people are bad to each other. They know that their parents are fighting. They know that their father isn’t coming to Florida and that it’s more complicated than “he’ll be there soon.” And I feel like — this is a very long winded way of getting to the fact that it becomes very clear to me that I think this part of why your books have landed with so many generations of children: that you honor this clear-eyed truth about children, in a very loving and sophisticated way, in the books you write.

DiCamillo: I have to say that I don’t know what I’m doing. All I know is that that kid — what’s the name of the child psychologist? Robert…

Tippett: Robert Coles.

DiCamillo: Yeah, and I think that I would love to read that, and then I also think, Don’t read that, because so much of what I do is instinctual. And I think it’s — the instinct comes from the eight-year-old in me that is just kind of right at the surface, for some reason, and it’s the hope and fear of that kid that helps guide me through the stories.

And then, also, the stories always — and you’ve heard me say this before — they are a way to access something much smarter than I am, and wiser than I am. And that eight-year-old in me walks with me as we find that smarter, better place. Does that make sense?

Tippett: It does, and I’ve had this experience of people who are not just good with children, but wise with children, that there’s a way in which — and I feel this in Robert Coles, I feel it in you — sometimes we talk — we talk, culturally, about all that we lose when we move from childhood to adulthood. And I feel like some people — in you and Robert Coles — that you manage to keep very alive this effervescence and this wide-eyed wonder, capacity for wonder.

DiCamillo: Well, you know —

Tippett: And maybe also — maybe also just that very direct frankness about reality.

DiCamillo: I was so — I was really, really small as a kid, and — small for my age. And then I looked really insubstantial, like a strong wind would blow me away, and I was always being condescended to by adults. But yet, I was really a sarcastic kid and a kid with a big vocabulary, and I always wanted to feel seen. And that’s what I loved about going into classrooms and talking to kids, was like — and I loved it. Doing a signing line, it was always like, it was three seconds, 30 seconds, whatever; it was a chance to let the kid know that I saw them, and I saw them as an individual, as a human being, and just, it was thrilling to make that connection. And it must be — it goes back to that eight-year-old that’s right at the surface for me. It’s just like, I just remember what it was like to feel invisible, to feel like you weren’t — or that you had to protect the adults by pretending that you believed the lies that they were telling you.

Tippett: [laughs] Right.

DiCamillo: And so it’s just one — even in the smallest interaction with a kid, Krista, you can let them know that you absolutely see them there, and with all their intelligence and all their history and all it was electric, sometimes, to do that, because kids don’t always get it, you know?

And it’s funny, because a lot of times, like when Despereaux came out, I would get asked, again and again, Why do you think mice figure so prominently in children’s literature? And I always wanted to say, Are you kidding? It’s because that’s how we treat kids. It’s just kind of like you’re in the way, you’re small, you’re powerless, and it feels very familiar to a kid.

Tippett: So that’s The Tale of Despereaux. And now, more recently, there’s the generation of kids who’ve been — for whom Flora & Ulysses is what they know of Kate DiCamillo. And Flora & Ulysses is a graphic novel, right? It’s a little different.

DiCamillo: It has graphic novel elements.

Tippett: Elements, yeah. But I’d just like to come back to this point about — when you just were describing yourself as an eight-year-old, I’m kind of — you know, how Flora is this very articulate, well-spoken, smart, natural-born cynic, [laughter] self-proclaimed, and that she constantly refers to her favorite book, which is called Terrible Things Can Happen to You! exclamation point, which is not the book any of us would give our children, but it’s probably the one that they would understand.

DiCamillo: [laughs] I’m sorry for laughing at my own joke, but it’s just so funny. [laughs]

Tippett: It’s so perfect. [laughs] Yeah.

DiCamillo: Yeah. But you know — wait, I had something to say back there, about Flora & Ulysses and the natural-born cynic, and —

Tippett: Okay, take your time.

DiCamillo: Well, it’s that I want to get to — and you can help me with pronunciation — Rilke? Am I saying it right? You’re the expert.

Tippett: You have got Rainer Maria Rilke in Flora & Ulysses, yes. Yes.

DiCamillo: Yes. Yes, I do. And more to the point, I have Rilke’s Book of Hours here, the Anita Barrows and Joanna Macy one. And I brought it with me because you were talking about the comfort that can be found in — what can save you; reading. But also, this I come back to, this quote, so much. This is in the introduction: “Rilke never lost his conviction in the utter reality of the world, or in our human capacity to redeem it through that act of transforming attention, which is naming — or love.” And that’s being seen.

And that’s — and when you talk about the magic in the books, the magic is just looking and wondering. You know, who knows what’s inside that squirrel? That squirrel could write poetry. And it’s like, that’s what we let go of when we’re adults, because, I think, it hurts so much to see how alive the world is and that everything is sentient, every being. And so you just kind of close down to that. But that is so much a part of how we see the world as kids. And for whatever reason, I can still access that, and that’s part of where the stories come from. Does that make sense?

Tippett: Yeah. Yeah, and that — where the stories come from is also a magical, mysterious question.

DiCamillo: Yeah. Do you want to go down that rabbit hole?

Tippett: Sure.

DiCamillo: Okay, where do the stories come from, Krista? [laughs]

Tippett: [laughs] I don’t know, but you hear voices, and they are people who then come to life and have their own opinions and reveal their stories.

DiCamillo: Right, it is — anybody who knows, can say — I don’t — it’s a mystery. It’s a mystery. And there are things that you can do, like — as I say to the kids when they ask where the ideas come from, it’s just like, do you know what eavesdropping is? There are things that you can do — you can pay attention all the time. I talk about a Flannery O’Connor quote: The writer must never be ashamed of staring. There is nothing that does not require her attention — I’ve changed the pronoun there.

But it’s just like, everything is your business. That’s kind of how I feel. It’s like, I pay attention to all of it. And then you don’t know — it’s kind of like walking around with a divining rod in your hand, and you think, Here? Here? Does this — and then a word will appear, and it’s like, yeah, dig here; or a character name. But I don’t usually start with story ideas. I just start with an image or a name, and then a constellation of things will come around that. I know, Oh, this belongs with this, and this belongs with this. And then I follow all that to the story, with my eight-year-old as the guide.

Tippett: It’s so mysterious. There’s someplace you — there’s a piece of writing by Ursula Le Guin that you’ve…

DiCamillo: That’s my other book that I brought along today.

Tippett: Oh, you did? I saw you read this to someone; would you like to read it here?

DiCamillo: It is — it just electrified me when I read it. And it’s from an essay called “The Operating Instructions.” Is that what you’re thinking of?

Tippett: Yeah. It feels to me like it helped you name something really important about this, about what you do and why, and what happens, and that mystery that happens.

DiCamillo: Yeah, and just the community of it, which is interesting, because reading is a solitary act.

So she says, “Nobody can do anything very much, really, alone.

“What a child needs, what we all need, is to find some other people who have imagined life along lines that make sense to us and allow some freedom, and listen to them. Not hear passively, but listen. Listening is an act of community, which takes space, time, and silence.

“Reading is a means of listening.

“Reading is not as passive as hearing or viewing. It’s an act: you do it. You read at your pace, your own speed, not the ceaseless, incoherent, gabbling, shouting rush of the media. You take in what you can and want to take in, not what they shove at you fast and hard and loud in order to overwhelm and control you. Reading a story, you may be told something, but you’re not being sold anything. And though you’re usually alone when you read, you are in communion with another mind. You aren’t being brainwashed or co-opted or used; you’ve joined in an act of the imagination.”

I just — the reason this — I’ll read one more thing from that. “The reason literacy is important is that literature is the operating instructions. The best manual we have. The most useful guide to the country we’re visiting, life.”

Tippett: “Life.”

DiCamillo: And why wouldn’t that matter so much — it’s so important for kids, to tell them — it goes back to that thing of, Oh, don’t talk about those hard things, because you don’t — but golly. Kids are — it’s, like you said — aware of everything that’s going on, and what a disservice not to talk to them. And also, at the same time, what a disservice not to offer them hope and love, because that’s what stories do, too. But they also need to tell the truth. And the truth is that it’s really difficult to be here. It is a huge gift to be here. It’s beautiful here. And it’s also challenging.

[music: “Dance of Felt” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’ve thought about you in this time, when I see these big articles in the newspaper, or these analyses going around, about children who lost time in school because of the pandemic as this “lost generation”. And I find — I mean, I find that so upsetting on many levels, including just children reading that they are the lost generation, or being told that, just at the most superficial level. I also feel like this — what you see and how you see them and how you honor the fact that they know so much and that they deserve to have both heartbreak and hope cultivated in them, is one response to this idea of the lost generation. And I found, when I was getting ready to talk to you, this exchange you had with another writer — Matt de la Peña? Is that his name?

DiCamillo: Matt de la Peña, yes. Yes.

Tippett: Who was asked this question — and I think this is a parent’s question, too. How much can you — the thing you want to do is shield. I think he said, “How honest should we be with our readers? Is it the job of the writer for the very young to tell the truth or preserve their innocence?” And I just want you to talk through with me what your response was — because you wrote such a beautiful and profound letter in response to that question. Was that all in you, or was that also a moment where the act of writing something down helped you say what you knew?

DiCamillo: I didn’t know how I was going to say it until I sat down and tried to say it. And I haven’t looked at that for a while, and you all have it here, waiting for me, and it actually hurts my — I mean, I could read it, or I could flap my arms and fly to the moon; which one would you like me to do?

Tippett: [laughter] Well, then, why don’t you read it, because I want you to stay in the studio. No, I — yeah, because I think it is exquisite. And it’s kind of out there on the internet as this exchange — I don’t think you’ve ever read it out loud.

DiCamillo: Oh no, I haven’t.

Tippett: So, why don’t you. Please do, read it for us.

DiCamillo: “Dear Matt,

“… You asked how honest we, as writers of books for children, should be with our readers, whether it is our job to tell them the truth or preserve their innocence.

Here’s a question for you: Have you ever asked an auditorium full of kids if they know and love Charlotte’s Web? In my experience, almost all of the hands go up. And if you ask them how many of them cried when they read it, most of those hands unabashedly stay aloft.

“My childhood best friend read Charlotte’s Web over and over again as a kid. She would read the last page, turn the book over, and begin again. A few years ago, I asked her why.

“‘What was it that made you read and reread that book?’” I asked her. “‘Did you think that if you read it again, things would turn out differently, better? That Charlotte wouldn’t die?’

“‘No,’” she said. “‘It wasn’t that. I kept reading it not because I wanted it to turn out differently or thought that it would turn out differently, but because I knew for a fact that it wasn’t going to turn out differently. I knew that a terrible thing was going to happen, and I also knew that it was going to be okay somehow. I thought that I couldn’t bear it, but then when I read it again, it was all so beautiful. And I found out that I could bear it. That was what the story told me. That was what I needed to hear. That I could bear it somehow.’

“So that’s the question, I guess, for you and for me and for all of us trying to do this sacred task of telling stories for the young: How do we tell the truth and make that truth bearable?

“When I talk to kids in schools, I tell them about how I became a writer. I talk about myself as a child and how my father left the family when I was very young. Four years ago … ”

— this would have been a lot longer — [laughs]

“… I was in South Dakota, in this massive auditorium, talking to 900 kids, and I did what I always do: I told them about being sick all the time as a kid and about my father leaving. And then I talked to them about wanting to write. I talked to them about persisting.

“During the Q&A, a boy asked me if I thought I would have been a writer if I hadn’t been sick all the time as a kid and if my father hadn’t left. And I said something along the lines of ‘I think there is a very good chance that I wouldn’t be standing in front of you today if those things hadn’t happened to me.’ Later, a girl raised her hand and said, ‘It turns out that in the end you were stronger than you thought you were.’

“When the kids left the auditorium, I stood at the door and talked with them as they walked past. One boy — skinny-legged and blond-haired — grabbed my hand and said, ‘I’m here in South Dakota and my dad is in California.’ He flung his free hand out in the direction of California. He said, ‘He’s there and I’m here with my mom. And I thought I might not be okay…’

— I don’t know if I can do this without crying. —

“‘But you said today that you’re okay. And so I think that I will be okay, too.’

“What could I do?

“I tried not to cry. I kept hold of his hand.

“I looked him in the eye.

“I said, ‘You will be okay. You are okay. It’s just like that other kid said: you’re stronger than you know.’

“I felt so connected to that child.

“I think we both felt seen.

“My favorite lines of Charlotte’s Web, the lines that always make me cry, are toward the end of the book. They go like this: ‘These autumn days will shorten and grow cold. The leaves will shake loose from the trees and fall. Christmas will come, then the snows of winter. You will live to enjoy the beauty of the frozen world, for you mean a great deal to Zuckerman and he will not harm you, ever. Winter will pass, the days will lengthen, the ice will melt in the pasture pond. The song sparrow will return and sing, the frogs will awake, the warm wind will blow again. All these sights and sounds and smells will be yours to enjoy, Wilbur — this lovely world, these precious days …’

“I have tried for a long time to figure out how E. B. White did what he did, how he told the truth and made it bearable.

“And I think that you, with your beautiful book about love, won’t be surprised to learn that the only answer I could come up with was love. E. B. White loved the world. And in loving the world, he told the truth about it — its sorrow, its heartbreak, its devastating beauty. He trusted his readers enough to tell them the truth, and with that truth came comfort and a feeling that we are not alone.

“I think our job is to trust our readers.

“I think our job is to see and to let ourselves be seen.

“I think our job is to love the world.

“Love,

“Kate”

That just about killed me. [sniffles] Sorry.

Tippett: It’s quite amazing. That line in the middle, “That’s the question … for you and for me and for all of us trying to do this sacred task of telling stories for the young: How do we tell the truth and make that truth bearable?”

DiCamillo: Yeah. It’s an overwhelming thing that you think, gosh — yeah. I mean, it is; it is a sacred task. It really is. And I feel so fortunate to get to do it, and I realize what a huge responsibility it is.

[music: “Blood Petal” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I really love — I just kind of want to circle back to this communal experience that reading is. I think you’ve said that reading is communal, even if it’s one person. And you’ve also talked about how, as a writer, that still, the reader finishes the book.

DiCamillo: Yeah, absolutely. It’s not done until somebody that I never know and will never talk to and will never meet reads it. That’s when it’s done.

Tippett: You said somewhere, “And they sit, and they exist in this world” that somehow came out of you. And then you said, “We exist in it together.” I also have that feeling about a conversation like this, like you and I are speaking right now, and then later, other people will join, and it will be as if they are sitting in the room with us.

DiCamillo: Yeah, that’s the great gift of what you do, and thank you for letting me come along for that ride. It does, it makes me part of that community, too, the community of — you know, I always think that it’s one of the most — I walk around thinking about this all the time, how important this is and how to keep it alive for myself and access it, particularly in these really difficult times; and that’s wonder.

And that’s so much of what happens when you’re a part of a conversation — or just that feeling of wonder and amazement, which is appropriate for every minute of every day of being in the world. It is amazing. And in order to survive, we have to close down a lot of that, because there’s so much that fills you with wonder that you wouldn’t — I mean, it’s miraculous. It’s miraculous that I was able to use the parking meter out here. [laughter] Do you know what I mean? It’s just like, how do we cultivate that wonder in ourselves?

And to me, books are the constant reminder to do that. And my notebook that I always have with me is the visual representation of, “pay attention; pay attention; pay attention.” And “pay attention” is wondering and marveling.

Okay, I’ll get off my soapbox now.

Tippett: No, that’s okay, it’s your — it’s a good soapbox. [laughs]

DiCamillo: [laughs] Do you admire it? Do you like my soapbox?

Tippett: I do; I like it very much.

Here’s something that — and my daughter said about The Tale of Despereaux. She said it was the first time that she really thought about — she had this experience, in the story, of “many lives” — I wrote this down — who “magically affected each other and overlapped in some secret way” — that this was her first experience of that — “and of falling in love with multiple people, and then this joy of realizing that their lives intertwined.”

DiCamillo: Wow. Wow. That’s — that kind of undoes me, to hear that, you know?

Tippett: [laughs] But, you know, what you just said, that is a description of what is happening all the time, in all of our lives, but we don’t wonder at it.

DiCamillo: Right? No, we don’t. If you pay attention, you’re filled with wonder, because who wouldn’t be, right? But we get so caught up in worrying, in being angry that we just, we don’t stop to marvel. And I think that if you walk through a neighborhood with a kid or a toddler, it’s just like, wait! Everything is fascinating. And I don’t want to let that go, because that’s a great gift. It grounds you.

I know I still need to get places on time; I still — I had a friend in elementary school, Cathy Lord, and I just, I loved her. She would sit at the back of the classroom and she would ask to sharpen her pencil like every three minutes because what she wanted to do was look at what everybody was doing. It wasn’t — she was just so interested. And I think about her when I sit down to write. It’s like, I think, Be like Cathy Lord on the way to the pencil sharpener. [laughter] I mean, everything that everybody was doing was fascinating to her. And that is a way to be in the world. You let your guard down that way, if you’re just curious and filled with wonder.

Tippett: There’s this element in — I mean, I haven’t checked this, but I think in every single story and every single book, there’s some connection between animals and also human courage. And, I mean, starting with Winn-Dixie, the dog, but also there’s a pig and a fierce goat, a rabbit, a mouse, a villainous rat, an elephant, a crow — and that’s just — doesn’t even cover it.

DiCamillo: Scratch the surface, yeah.

Tippett: And it also strikes me that this connection to animals and a solace in animals, somehow a way of — I don’t know. I was with a very erudite friend of mine; I hadn’t seen her for a year and a half, through the pandemic, and she had her dog. They had gotten this dog. And she just talked about how the experience of unconditional love with this dog had just gotten her through. And, I don’t know, I feel like that, also, is somehow in — so that something we’re recognizing, but it’s something, also, that is in your books, in your stories, and that maybe kids know. I don’t know.

DiCamillo: Yeah, or it’s funny, that courage bit, nobody’s pointed that out. But it’s like, I talk a lot about kids always want to know, Why all the animals? And the answer is so complex. The obvious answer is, I love animals. And then the next obvious answer is that so much of what I read as a kid had those anthropomorphized animals, and that then takes me closer to being a kid. But it’s also — and it’s not calculated, on my part, but it is very much true — that we, as readers, whether we’re adults or kids, we let down our guard a little bit more easily for an animal character, I think. It’s a shortcut into the human heart.

But then — it’s funny that it took forever for this to occur to me — but I grew up with a standard poodle named Nanette, and all that sickness that I had, Nanette was like, we always used to say she must’ve been a nurse in a previous life. It was the dog that was up with me in the middle of the night, and on the bathroom floor with me, and she really took care of me. And so it could be that, too. And she certainly gave me courage.

But you know what else, when you think about it, Krista, it’s just, it’s that thing about everything — and all the science points to this now, which I don’t need to tell you about. But everything — everything — is sentient.

And we know that, and then we forget it. And sometimes we forget it because it’s too painful to remember it. But we know it when we’re kids. Everything’s alive. Everything has a heart and soul. And it comes from that, too.

Tippett: I think Robin Wall Kimmerer said, we never learn that something is less conscious than we thought, [laughs] when we’re looking at the natural world. We always just keep learning there’s more going on.

DiCamillo: And speaking of her, I mean, she just popped through my head when I said that, because it’s like, every tree I walk past is like the “standing people,” from — it’s just like, everything. Everything. And I’ll admit it — I talk to the trees when I go past.

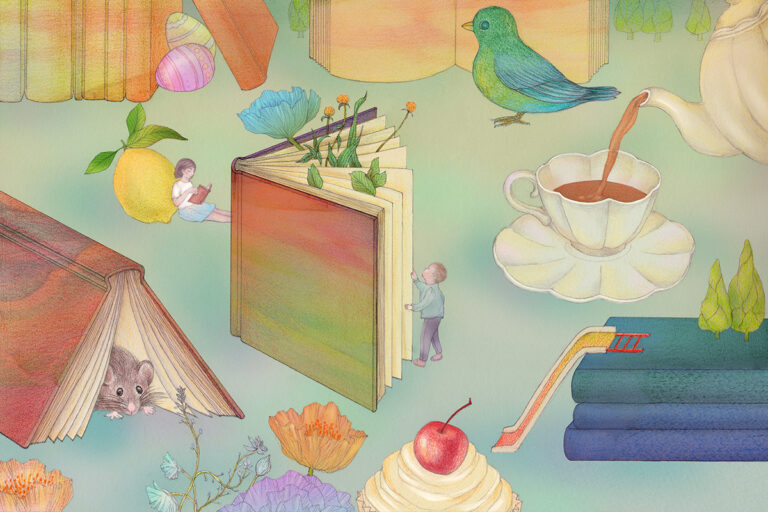

Tippett: [laughs] It also — the pictures that go along with your stories, the way a story unleashes pictures in somebody else’s mind, but also the art that goes along with your stories. [laughs] I just have to tell you one thing my daughter has said so many times, is she’ll just shake her head and say, “I will never get over my sadness that adults learned to do stories without pictures.”

DiCamillo: [laughs] Don’t you remember what it was like when you were a kid, and you would flip through a book and go, Oh, there aren’t any pictures. And then how you would just tumble down into the hole of every, like — because I had my mom’s Book House books; have you ever seen those? And they would have those full-color plates in it? And it was like, you would just get to one of those and just study it and study it? I’m with her on that. That’s one of the fantastic things about writing books for kids, is the art, you know? It’s just a whole other layer of magic, and also just another shortcut to the heart.

[music: “Running a Quick Errand” by Sanctus Audio]

Tippett: So I would love for you…

DiCamillo: Uh-oh.

Tippett: …when you won your second — sorry, were you going to say something?

DiCamillo: No, no. I’m just wondering where you’re going.

Tippett: [laughs] No, well, when you won your second Newbery Medal, in 2014, in the acceptance speech you talked about the word “capacious.” And it feels like a word we need right now — maybe always, but certainly now — and that we should be teaching our children the word “capacious.” [laughs] I also feel like that must’ve been — I could tell when you gave that speech, that you were — giving that speech was inviting you to say some things that you hadn’t said. You said, in that roomful of librarians and, I’m sure, writers, readers, for sure, “We have been given the sacred task of making hearts large through story. We are working to make hearts that are capable of containing much joy and much sorrow, hearts capacious enough to contain the complexities and mysteries…of ourselves and of each other.”

DiCamillo: Yeah. That makes me cry, too, because that’s it. That’s it. And it’s what I need, too, and what I get from books. And to think about getting to be a part of that for a kid is just huge, you know? And it goes back to the Ursula Le Guin piece, that — “The Operating Instructions,” and also that thing of being in community with somebody, across time and space, through story.

Tippett: Through story and reading and writing.

DiCamillo: And writing, yeah. Yeah, okay. How often do people cry on this show? [laughs] Am I like, in a small, sad club?

Tippett: [laughs] Well, you have a capacious heart, so you’re more open to that.

I did ask if you had favorite quotes of your characters. Did that question make sense?

DiCamillo: That came through, and it sure did make sense. And it got at a couple things, which are very interesting to me. One of them is that thing of the characters being independent of me and surprising me, which is — and of course, they always do. And I brought — there are quotes that go through my head from stories; one of them is the little Leo Matienne in The Magician’s Elephant, who always is so upbeat and says, “What if? Why not? Could it be?” which is a wonderful refrain to have in your head as a positive thing: Why not? What if? Could it be?

But I thought of, when you posed that question, I thought of — I don’t know if you read Louisiana’s Way Home.

Tippett: I have not read that one, no.

DiCamillo: So Louisiana is raised by her grandmother, and her grandmother — well, I just, you know, she ends up — her grandmother is more than a piece of work; she’s probably a little mentally unwell. And she ends up leaving her. And so Louisiana is abandoned. This is the very end of the book.

Louisiana says — this is, happily, in first-person, so it’s fun to read: “I have respected your wishes. I have not come searching for you, but I have crossed the Florida-Georgia state line many, many times since we last spoke, and I look for you every time I cross over. I know that you will not be there, but I look anyway.

“And I dream about you.

“In my dream, you are standing in front of the vending machine from the Good Night, Sleep Tight, and you are smiling at me, using all of your teeth. You say, ‘Select anything you want, darling. Provisions have been made. Provisions have been made.’

“I am so happy when you show up in my dreams and say those words to me.

“Thank you for picking me up in the alley of the Louisiana Five-and-Dime.

“Thank you for teaching me to sing.

“I don’t know if you made it to Elf Ear or not. But I want you to know that there is no curse of sundering upon my head.

“I love you, Granny.

“I forgive you.”

And so that, Krista, is like, she said those words at the end, which destroyed me, and I had no — I didn’t plan for her to say them. And I can trace those words back to — you know where? To your show.

Tippett: Really?

DiCamillo: Yeah, I can’t remember who was on; I think it’s the StoryCorps guy.

Tippett: Oh, David Isay.

DiCamillo: Yeah, talking about what you should say —

Tippett: Oh, the things we say to the —

DiCamillo: Yes, and should I say them?

Tippett: Yeah. Things people need to say before they go.

DiCamillo: Before they die. And they are: Thank you. I love you. I forgive you. Can you forgive me?

And when I heard that, I almost fell off the treadmill, because it so directly spoke to what I needed to say to my father. And I wrote him that.

And then what happens is that those words come back through the fullness of story, in a way that I did not anticipate at all, and freed me again, and hopefully will free somebody else, through the miracle of story.

And that — and all that goes on subterranean, on a subterranean level, for me, and for the reader, too, probably. But that’s what I thought of when you asked that question. And those words go through my head all the time. And they’re Louisiana’s words, but they came — I know where they came from, I just didn’t anticipate her saying them.

Tippett: [laughs] I’m so glad I asked you that question.

DiCamillo: Yeah.

Tippett: I feel like — you talk a lot about this, that somehow, what things come back to you, for you, is home. And that’s somehow what — it’s always there, for all of us, and it’s always true throughout the course of our lives, and whether we are conscious of how it’s affecting us or not.

I was looking at the last sentence of the first chapter of Because of Winn-Dixie

“And the two of us, me and Winn-Dixie, started walking home.” And that — to me, I had this picture of you; you, Kate — that was your first book, and then you’ve been walking home ever since, and helping other people do that, with every book that comes after it.

DiCamillo: What a beautiful thing to say, a. And b, yes, what a grand gift that has been, to get to find my way home again and again, through story, and then to have other people with me on the journey. Can you imagine what a huge honor that is?

And also, back to the sacred task part of it, when you think how I keep on hoping, I feel duty bound to tell stories. It is at the risk of sounding grandiose, it’s what I got to come here to do. And so it’s what I want to keep on doing.

[music: “Eventide” by Gautam Srikishan]

Tippett: Kate DiCamillo has written many bestselling books, some of which have been turned into operas and movies — Because of Winn-Dixie, The Tale of Despereaux, The Magician’s Elephant, Flora & Ulysses, and The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane. She’s also the author of the Mercy Watson series and the novel Ferris.

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Eddie Gonzalez, Lucas Johnson, Zack Rose, Julie Siple, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Gautam Srikishan, Cameron Mussar, Kayla Edwards, Tiffany Champion, Andrea Prevost, and Carla Zanoni.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. We are located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. Our closing music was composed by Gautam Srikishan. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

Our funding partners include:

The Hearthland Foundation. Helping to build a more just, equitable and connected America—one creative act at a time.

The Fetzer Institute, supporting a movement of organizations that are applying spiritual solutions to society’s toughest problems. Find them at fetzer dot org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, Dedicated to cultivating the connections between ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting initiatives and organizations that uphold sacred relationships with the living Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia-dot-org.

And, the Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.