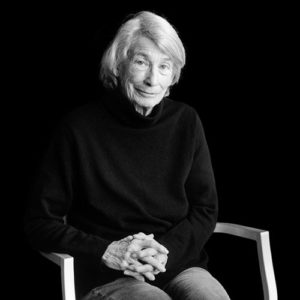

Mary Oliver

“I got saved by the beauty of the world.”

The late poet Mary Oliver is among the most beloved writers of modern times. Amidst the harshness of life, she found redemption in the natural world and in beautiful, precise language. She won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award among her many honors — and published numerous collections of poetry and also some wonderful prose. Krista met with her in 2015 for this rare, intimate conversation. We offer it up anew, as nourishment.

Image by Angel Valentin, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Mary Oliver published over 25 books of poetry and prose, including Dream Work, A Thousand Mornings, and A Poetry Handbook. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1984 for her book American Primitive. Her final work, Devotions, is a collection of poetry from her more than 50-year career, curated by the poet herself. She died in 2019.

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang

Krista Tippett, host: The late poet Mary Oliver is among the most beloved writers of modern times. Amidst the harshness of life, she found redemption in the natural world and in beautiful, precise language. She sat with me for a rare intimate conversation, and we offer it up anew as nourishment for now.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Mary Oliver: “Whoever you are, no matter how lonely, / the world offers itself to your imagination, / calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting — / over and over announcing your place / in the family of things.”

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

Mary Oliver was born in 1935 and grew up in a small town in Ohio. In her later years she spoke openly of profound abuse she suffered as a child. She won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, among her many honors, and published numerous collections of poetry and, also, some wonderful prose. She lived and wrote for five decades on Cape Cod. I met with her in Florida in 2015, where she spent the last few years of her life.

The question I always start with, whether I’m interviewing a physicist or a poet, is I’d like to hear whether there was a spiritual background to your life — to your early life, to your childhood — however you would define that now.

Oliver: Well, I would define it, now, very differently from when I was a child. I was sent to Sunday school, as many kids are, and then I had trouble with the resurrection, so I would not join the church. But I was still probably more interested than many of the kids who did enter the church. It’s been one of the most important interests of my life, and continues to be. And it doesn’t have to be Christianity; I’m very much taken with the poet Rumi, who is Muslim, a Sufi poet, and read him every day. And I have no answers, but have some suggestions. I know that a life is much richer with a spiritual part to it. And I also think nothing is more interesting. So I cling to it.

Tippett: And then you talk about growing up in a sad, depressed place, a difficult place. You don’t belabor this, I mean, and in other places — there’s a place you talk about you were one of many thousands who’ve had insufficient childhoods, but that you spent a lot of your time walking around the woods in Ohio.

Oliver: Yes, I did, and I think it saved my life. To this day, I don’t care for the enclosure of buildings. It was a very bad childhood — for everybody, every member of the household, not just myself, I think — and I escaped it, barely, with years of trouble. But I did find the entire world, in looking for something. But I got saved by poetry, and I got saved by the beauty of the world.

Tippett: And there’s such a convergence of those things then, it seems, all the way through, in your life as a poet.

Oliver: Yes, it is. It is a convergence. And I have a little difficulty now, having lived for 50 years in a small town in the North — I’m trying very hard to love the mangroves. [laughs] It takes a while.

Tippett: Well, I know. I have to say, you and your poetry, for me, are so closely identified with Provincetown and that part of the world and that kind of dramatic weather, that kind of shore. And so when I had this amazing opportunity to come visit you — and I said, Oh great, we’re going to Cape Cod! No, we’re going to Florida. [laughs]

Oliver: Yes, I just sold my condo to a very dear friend, this summer, and I bought a little house down here, which needs very serious reconstruction, so I’m not in it yet. But sometimes, it’s time for the change.

Tippett: Though for all those years, for decades of your writing, this picture was there of you, this pleasure of walking and writing and, I don’t know, standing with your notebook and actually writing while you’re walking. [laughs]

Oliver: Yes, that’s how I did it.

Tippett: And it is. And it seems like such a gift, that you found that way to be a writer and to have that daily — have a ritual of writing.

Oliver: Well, as I say, I don’t like buildings. The only record I broke in school was truancy. I went to the woods a lot, with books — Whitman in the knapsack — but I also liked motion. So I just began with these little notebooks and scribbled things as they came to me, and then worked them into poems, later.

And always, I wanted the “I.” Many of the poems are: I did this, I did this, I saw this. I wanted the “I” to be the possible reader, rather than about myself. It was about an experience that happened to be mine, but could well have been anybody else’s. And that was my feeling about the “I.” I have been criticized by one editor, who felt that the “I” would be felt as ego, and I thought, No, well, I’m going to risk it and see. And I think it worked. It enjoined the reader into the experience of the poem. I became the kind of person who did the walking and the scribbling, but shared it if they wanted it. Yes.

Tippett: And you also use this word — there’s this place where you’re talking about writing while walking, listening deeply, and — I love this — “listening convivially” …

Oliver: [laughs] Yes. Yeah.

Tippett: … and listening, really, to the world.

Oliver: Listening to the world. Well, I did that, and I still do it. I still do it.

Tippett: I was going to ask you if you thought you could have been a poet in an age when you probably would have grown up writing on computers.

Oliver: Oh, now? Oh, I very much advise writers not to use a computer.

Tippett: But it seems to me that more than the computer being the problem, the sitting at a desk would be a problem.

Oliver: That’s a problem; lots of things are problems. As I talk about it in the Poetry Handbook, discipline is very important. The habit — I think we’re creative all day long. We have to have an appointment, to have that work out on the page, because the creative part of us gets tired of waiting, or just gets tired. And It’s helped a lot of students, young poets, doing that — to have that meeting with that part of oneself, because there are, of course, other parts of life.

I used to say I gave my — when I had jobs, which wasn’t that often. But I’d say: I give my very best, second-class labor to the —

Tippett: To the job.

Oliver: Because I’d get up at 5, and by 9, I’d already had my say.

Tippett: And also, when you write about that, the discipline that creates space for something quite mysterious to happen, you talk about that “wild, silky part of ourselves.” You talk about the “part of the psyche that works in concert with consciousness and supplies a necessary part of the poem — a heart of the star as opposed to the shape of the star, let us say — exists in a mysterious, unmapped zone: not unconscious, not subconscious, but cautious.”

Oliver: What is that from?

Tippett: That’s from the Poetry Handbook. [laughs]

Oliver: [laughs] It’s been awhile.

Tippett: It’s great. But you say, you promise — it learns quickly what sort of courtship it’s going to be. You’re saying the writer has to be kind of in courtship with this elusive, essential but elusive, cautious — you say “cautious” — part, and that if you turn up every day, it will learn to trust you.

Oliver: Yes, yes, yes. I remember that.

Tippett: This is a very practical way about talking about something that’s quite —

Oliver: Trust is very important.

Tippett: Yes, and that’s the creative process.

Oliver: That is the creative process. It’s also true that I believe poetry — it is a convivial, and a kind of — it’s very old. It’s very sacred. It wishes for a community — it’s a community ritual, certainly. And that’s why, when you write a poem, you write it for anybody and everybody. And you have to be ready to do that out of your single self. It’s a giving. It’s always — it’s a gift. It’s a gift to yourself, but it’s a gift to anybody who has a hunger for it.

Tippett: And I wonder if it’s something about this process you describe, where you’ve applied the will, but also the discipline, to reach and, also, make room for something that’s very deep in us, right? I mean, I love this language, “this wild, silky part of ourselves.” I don’t know — maybe the soul.

Oliver: It’s become a nasty word, lately …

Tippett: I know it has.

Oliver: … because it’s used — it’s become a lazy word. It’s too bad.

Tippett: It’s cliched.

Oliver: Overused.

Tippett: So “the silky part” — let’s just call it that. But I mean, when you offer that — I mean, poetry does create a way to offer that, in a condensed form, vivid form.

Oliver: Yes. And very often — you know, it was Blake who said, “I take dictation.” With that discipline and with that willingness and wish to communicate, very often things very slippery do come in that you weren’t planning on receiving them. But they do happen. I have very rarely, maybe four or five times in my life, I’ve written a poem that I never changed, and I don’t know where it came from. But it does happen. But it happens among hundreds of poems that you’ve struggled over.

Tippett Do you know which — do you know what some of those are? Do you know what they are now, still?

Oliver: Well, the Percy one was one — “The First Time Percy Came Back.” I never changed a word of that. And there are others. I can’t remember, but there are a few. Of course, there are also poems that I just write out and then I throw them out — [laughs] lots of those.

Tippett: Well, and also, when you talk about this life of waking up in the morning and being outside, in this wild landscape, and with your notebook in your hand and walking — it’s so enviable, right? But then I know, when you’re — in the Poetry Handbook, there’s the discipline of being there, but there’s also the hard work of rewriting, and as you say, some things have to be thrown out.

Oliver: Oh, many, many, many have to be thrown out, for sure.

Tippett: There’s an unromantic part to the process, as well.

Oliver: Well, that’s an interesting word. Somebody once wrote about me and said I must have a private grant or something; that all I seem to do is walk around the woods and write poems. But I was very, very poor, and I ate a lot of fish, ate a lot of clams.

Tippett: Right. And I read that you weren’t just walking around the woods, you were gathering food, in those early years: mussels and clams and mushrooms and berries. Although you gave voice to this really lavish, even ornate beauty that you lived in …

Oliver: That’s how I saw it.

Tippett: … that was your daily — that was really your mundane world.

Oliver: Yes, that’s true.

Tippett: So there’s a question that you pose in many different ways, overtly and implicitly: How shall I live? In Long Life, you wrote, “What does it mean that the earth is so beautiful? And what shall I do about it? What is the gift that I should bring to the world? What is the life that I should live?” — which really is a question of moral imagination, and it’s the ancient, essential question. But I wonder how you think about how that question emerges and is addressed distinctively, in poetry and through poetry. What does poetry do with a question like that that other forms of language don’t?

Oliver: Well, I think I would disagree that other forms of language don’t, but poetry has a different kind of attraction.

Tippett: So what is that attraction in poetry?

Oliver: I think it’s the way it’s written. It’s the fact that it has been communal, for years and years and years, and we’ve missed it. But I do think poetry has enticements of sound that are different from literature — literature certainly has it, too, or some literature, the best literature — and it’s easier for people to remember. People are more apt to remember a poem, and therefore feel they own it and can speak it to themselves as you might a prayer, than they can remember a chapter and quote it. And that’s very important, because then it belongs to you. You have it when you need it.

But poetry is certainly closer to singing than prose. And singing is something that we all love to do or wish we could do. [laughs]

Tippett: And it goes all the way through you.

Oliver: Yes. It does indeed.

[music: “The Best Paper Airplane Ever” by Lullatone]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today resurfacing the poetry and solace of the late Mary Oliver.

[music: “The Best Paper Airplane Ever” by Lullatone]

I just wanted to read — I just love — I just want to read these. This is from Long Life, also: “The world is: fun, and familiar, and healthful, and unbelievably refreshing, and lovely. And it is the theater of the spiritual; it is the multiform utterly obedient to a mystery.”

Oliver: Well, you know, and it is. We all wonder who’s God, what’s going to happen when we die, all that stuff. And I don’t think it’s — maybe — it’s never nothing. I’m very fond of Lucretius.

Tippett: [laughs] Say some more.

Oliver: And Lucretius says, just, everything’s a little energy: you go back, and you’re these little bits of energy, and pretty soon, you’re something else. Now, that’s a continuance. It’s not the one we think of when we’re talking about the golden streets and the angels with how many wings and whatever, the hierarchy of angels — even angels have a hierarchy — but it’s something quite wonderful. The world is pretty much — everything’s mortal; it dies. But its parts don’t die; its parts become something else. We know that, when we bury a dog in the garden and with a rose bush on top of it; we know that there is replenishment. And that’s pretty amazing. And what more there might be, I don’t know, but I’m pretty confident of that one.

Tippett: And again, do you think spending your life as a poet and working with words and responding to the world in the way you have, as a poet, gives you, I don’t know, tools to work with? Because putting words around God or what God is or who God is or, I don’t know, heaven — it’s always insufficient.

Oliver: It’s always insufficient, but the question and the wonder is not unsatisfying. It’s never totally satisfying, but it’s intriguing, and also, what one does end up believing, even if it shifts, has an effect upon the life that you live, or the life that you choose to live or try to live. So it’s an endless, unanswerable quest. So I just, I find it endlessly fascinating.

And I think, also, religion is very helpful in people not thinking that they themselves are sufficient: that there is something that has to do with all of us that is more than all of us are.

Tippett: And that is what you do, because of the particular vision that you have: what you pay attention to, what you attend to, which is that grandeur, that largeness of the natural world, which — a couple of years ago when I was writing, I picked up your book A Thousand Mornings. Here’s the first one, “I Go Down to the Shore”:

“I go down to the shore in the morning / and depending on the hour the waves / are rolling in or moving out, / and I say, oh, I am miserable, / what shall — / what should I do? And the sea says / in its lovely voice: / Excuse me, I have work to do.”

Oliver: I love that.

Tippett: I love that, and I have to say, also, to me it was just — it’s so perfect. It kind of is like, what’s the point of bringing 50,000 new words into the world? This says it all.

Oliver: Well, I have had a rash, which seems to be continuing, of writing shorter poems.

Tippett: I noticed that, in your more recent poems.

Oliver: It probably is an influence from Rumi, whose poems are — many of them are quite short. But if you can say it in a few lines, you’re just decorating for the rest of it, unless you can make something more intense. But if you said what you want to say, you’re not going to make it more intense. You’re just going to repeat yourself.

So I’ve got a poem that will start the next book. I think it goes like this: “Things take the time they take. Don’t / worry. / How many roads did St. Augustine follow / before he became St. Augustine?”

Same kind of thing. What else is there to say?

Tippett: [laughs] That’s right.

Oliver: And that’s four lines, and that’s not a day’s work — [laughs] but the poem is done.

Tippett: And it speaks so completely perfectly to the “I” who’s reading the poem, even though it’s about St. Augustine. But it’s about all of us, right?

Oliver: Yeah, and people do worry that they’re not wherever they want to go. And St. Augustine, I had just read a biography of him, and he was all over the map, before he settled down.

Tippett: I’d like to talk about attention, which is another real theme that runs through your work — both the word and the practice. And I know people associate you with that word. But I was interested to read that you began to learn that attention without feeling is only a report; that there is more to attention than for it to matter in the way you want it to matter. Say something about that learning.

Oliver: You need empathy with it, rather than just reporting. Reporting is for field guides. And they’re great, they’re helpful, but that’s what they are. But they’re not thought provokers, and they don’t go anywhere. And I say somewhere that attention is the beginning of devotion, which I do believe. But that’s it. A lot of these things are said, but can’t be explained.

Tippett: I think your poem “A Summer Day” is maybe — is one of the best known.

Oliver: Yes it is. I would say that’s true.

Tippett: So my daughter, who is now 21 and all grown up, but who then was about 12, was assigned to memorize “A Summer Day” …

Oliver: “The Summer Day.”

Tippett: … “The Summer Day,” in sixth grade, and so she came home reciting this poem and, I felt, really embodying it. And we actually played it in the show. Anyway, I brought it, because I wanted you to hear it. And so remember, she’s not reading it. She’d learned it.

Aly Tippett: “The Summer Day”: “Who made the world? / Who made the swan, and the black bear? / Who made the grasshopper? / This grasshopper, I mean — / the one who has flung herself out of the grass, / the one who is eating sugar out of my hand, / who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down — / who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes. / Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face. / Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away. / I don’t know exactly what a prayer is. / I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down / into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass, / how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields, / which is what I have been doing all day. / Tell me, what else should I have done? / Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon? / Tell me, what is it you plan to do / with your one wild and precious life?”

Oliver: That’s a beautiful reading.

Tippett: Is that fun for you to hear?

Oliver: Yeah. How old was she then?

Tippett: She was about 12.

Oliver: Beautiful.

Tippett: But so many, so many young people, I mean, young and old, have learned that poem by heart, and it’s become part of them.

Oliver: One thing about that poem which I think is important is that the grasshopper actually existed, and yet I was able to fit him into that poem. And the sugar he was eating was part of frosting from a Portuguese lady’s birthday cake, which wasn’t important to the poem, but even seeing that little creature come to my plate and say: I’d like a little helping of that — it somehow fascinates me that — that’s just personal, for me, that it was Mrs. Segura, probably her 90th birthday cake or something.

Tippett: Did she ever read the poem? Did she ever know?

Oliver: No. She was past that. Her daughters may have, but — I never advertise myself as a poet. And there was that wonderful thing about the town, and that is, I was taken as somebody who worked, like anybody else. And I’d go — there was the one fellow who was the plumber, and we’d maybe meet in the hardware store in the morning.

Tippett: You mean in Provincetown?

Oliver: Yeah. And he’d say: Oh, hi, Mary, how’s your work going? I’d say: Pretty good, how’s yours? And it was the same thing. There was no sense of eliteness or difference. And that was very nice.

In fact, it is a funny story: when the Pulitzer Prize was announced, which I didn’t even know they’d turned the book in for, I was, at that time, as the whole town was doing, going out to the dump most mornings, which was a mess — that was before they cleaned up — to buy shingles. I was shingling the house, or some kind of thing. And a friend of mine came by, a woman who’s a painter. She said, Ha, what are you doing? Looking for your old manuscripts? [laughs] It was very funny.

Tippett: And you didn’t know? She’d heard the news?

Oliver: I knew, but my job in the morning was to go find some shingles. [laughs]

[music: “Causeway” by Ryan Teague]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Mary Oliver.

[music: “Causeway” by Ryan Teague]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, my 2015 conversation with the late, beloved poet Mary Oliver. We offer this up as nourishment for now.

I wanted to also name the fact that, as you said before, you’re not somebody who belabors what is dark, what has been hard. I think it’s important, and maybe helpful for people, because there’s so much beauty and light in your poetry, also that you let in the fact that it’s not all sweetness and light. And you did that a lot in the Dream Work book.

Oliver: I did. I did.

Tippett: And those poems are notably harder.

Oliver: And a lot of my — I didn’t know, at that time, what I was writing about. I really had no understanding.

Tippett: You mean, you didn’t realize that they were so hard, or you literally didn’t know what you were …

Oliver: No, there’s a poem called “Rage.”

Tippett: Yes.

Oliver: And I — it’s a she, and that’s perfect biography, unfortunately, or autobiography. But I couldn’t handle that material, except in the three or four poems that I’ve done; just couldn’t.

Tippett: Yeah, I mean, there’s a line in “Rage”: “in your dreams you have sullied and murdered, / and your dreams do not lie.”

Oliver: Well, that’s how I felt, but I didn’t know I was — certainly, I didn’t know I was talking about my father. Children forget. I mean, they don’t forget, but they forget the details. They just don’t know why they have nightmares all the time. It’s very difficult.

Tippett: Isn’t it incredible that we carry those things all our lives, decades and decades and decades?

Oliver: Well, we do carry it, but it is very helpful to figure out, as best you can, what happened and why these people were the way they were. And it was a very dark and broken house that I came from.

Tippett: There’s another — there’s that poem in there, “A Visitor,” which mentions your father. And there’s just, to me, this heartbreaking line, which also, I — I have my own story; we all do — “I saw what love might have done / had we loved in time.”

Oliver: “[H]ad we loved in time.” Yeah. Well, he never got any love out of me, or deserved it. But mostly — what mostly just makes you angry is the loss of the years of your life, because it does leave damage. But there you are. You do what you can do.

Tippett: And I think — you have such a capacity for joy, especially in the outdoors, right? And you transmit that. And it’s that joy — if you’re capable of that, how much more of it would there have been?

Oliver: Well, I saved my own life, by finding a place that wasn’t in that house. And that was my strength. But I wasn’t all strength. And it would have been a very different life.

Whether I would have written poetry or not, who knows? Poetry is a pretty lonely pursuit. And in many cases, I used to think — I don’t do it anymore — but that I’m talking to myself. There was nobody else that in that house I was going to talk to. And it was a very difficult time, and a long time. And I don’t understand some people’s behavior.

Tippett: And I guess what I’m saying, I think, is that it’s a gift that you give to your readers, to let that be clear: that your ability to love your “one wild and precious life” is hard won. And I mean, I feel like you also — for all the glorious language about God and around God that goes all the way through your poetry, you also acknowledge this perplexing thing. I mean, this was in Long Life: “What can we do about God, who makes and then breaks every god-forsaken, beautiful day?” [laughs]

Oliver: [laughs] Well, we can go back and read Lucretius.

Tippett: [laughs] What does Lucretius do, then?

Oliver: Well, Lucretius just presents this marvelous and important idea that what we are made of will make something else, which to me is very important. There is no nothingness, with these little atoms that run around — too little for us to see, but put together, they make something. And that, to me, is a miracle. Where it came from, I don’t know, but it’s a miracle. And I think it’s enough to keep a person afloat.

Tippett: [laughs] Let’s talk about your last couple of books, which also are an insight into you at this stage in your life, and then I’d love for you to read some poems. You have said that you were so captivated — that you were — I don’t know if you’ve said it this way, but it seems to me you’ve kind of written about being so captivated by the world of nature that you were less open to the world of humans, and that as you’ve grown older, as you’ve gone through life — what did you say — you’ve entered more fully into the human world and embraced it. Is that a good …

Oliver: True. It’s absolutely true.

Tippett: And was it passage of time?

Oliver: It was passage of time; it was the passage of understanding what happened to me and why I behaved in certain ways and didn’t in other ways. So it was clarity.

Tippett: You wrote really beautifully about the death of Molly, who you shared so much of your life with. And you wrote — I don’t know, I’m finding my notes — “The end of life has its own nature, also worth our attention.” I liked that line. And in some ways it feels to me, when I read your poetry of the last couple of years, that that’s really this territory you’re on, or at least part of it.

Oliver: Well, I should be.

Tippett: And I don’t mean you’re at the end of life, but just paying attention to —

Oliver: Well, I’ve been better. [laughs]

Tippett: [laughs] But just a different — it’s a different chapter.

Oliver: Well, it is. I mean, I had cancer a couple years ago, lung cancer, and it feels that death has left his calling card. I’m fine; I get scanned, as they do. I’m lucky. I’m very lucky. But all the same, you’re kind of shocked. This doctor, that doctor. I’m a bad smoker.

Tippett: And you’re still smoking.

Oliver: Yep, and last time, the doctor said, “Your lungs are good.” Well, you get good fortune, take it. And you keep smoking.

Tippett: There’s that poem “The Fourth Sign of the Zodiac,” in the new book.

Oliver: Yeah. How does that start? Which one is that? Oh — that’s one of the poems about cancer.

Tippett: Well, right. And you haven’t, I don’t think — have you spoken much about your cancer? I think people know that you were ill.

Oliver: No. People knew I was ill, and they didn’t know —

Tippett: They didn’t know what it was. In that poem, there’s a very passing reference to it.

Oliver: Oh yes, there is. There are four poems. One is about the hunter in the woods that makes no sound, all the hunters.

Tippett: It’s a little bit long, but do you want to read it?

Oliver: Sure. Oh, where’d I put my glasses? There they are. The fourth sign of the zodiac is, of course, Cancer. Oh, that’s the one I meant.

“Why should I have been surprised? / Hunters walk the forest / without a sound. / The hunter, strapped to his rifle, / the fox on his feet of silk, / the serpent on his empire of muscles — / all move in a stillness, / hungry, careful, intent. / Just as the cancer / entered the forest of my body, / without a sound.”

These four poems are about the cancer episode, shall we say; the cancer visit. [laughs] Did you want me to go on to these others?

Tippett: You want to go on? Is it too much?

Oliver: No. This is the second poem of these four:

“The question is, / what will it be like / after the last day? / Will I float / into the sky / or will I fray / within the earth or a river — / remembering nothing? / How desperate I would be / if I couldn’t remember / the sun rising, if I couldn’t / remember trees, rivers; if I couldn’t / even remember, beloved, / your beloved name.

“3. / I know, you never intended to be in this world. / But you’re in it all the same. // So why not get started immediately. // I mean, belonging to it. / There is so much to admire, to weep over. // And to write music or poems about. // Bless the feet that take you to and fro. / Bless the eyes and the listening ears. / Bless the tongue, the marvel of taste. / Bless touching. / You could live a hundred years, it’s happened. / Or not. / I am speaking from the fortunate platform / of many years, / none of which, I think, I ever wasted. / Do you need a prod? / Do you need a little darkness to get you going? / Let me be as urgent as a knife, then, / and remind you of Keats, / so single of purpose and thinking, for a while, / he had a lifetime.

“4. / Late yesterday afternoon, in the heat, / all the fragile blue flowers in bloom / in the shrubs in the yard next door had / tumbled from the shrubs and lay / wrinkled and faded on the grass. But / this morning the shrubs were full of / the blue flowers again. There wasn’t / a single one on the grass. How, I / wondered, did they roll or crawl back to / the shrubs and then back up to / the branches, that fiercely wanting, / as we all do, just a little more of / life?”

[music: “Breaking Down” by Clem Leek]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today resurfacing the poetry and solace of the late Mary Oliver.

There are some of your poems — and I think “The Summer Day” is one, and “Wild Geese” is another — that have just entered the lexicon.

Oliver: Yes, three: “The Summer Day,” “Wild Geese” — there’s one other I can’t remember, but, I would say, is the third one. But I don’t remember it.

Tippett: If you think of it, tell me. So “Wild Geese” is in Dream Work, and I’ve heard people talk about that — “Wild Geese” — as a poem that has saved lives. And I wonder if, when you write something like that — I mean, when you wrote that poem or when you published this book, would you have known that that was the poem that would speak so deeply to people?

Oliver: This is the magic of it — that poem was written as an exercise in end-stopped lines.

Tippett: As an exercise in what?

Oliver: End-stopped lines: period at the end of the line. I was working with a poet; I had her in a class.

Tippett: So it was an exercise in technique. [laughs]

Oliver: Yes. And not every line is that way; I was trying to show the variation, but my mind was completely on that. At the same time, I will say that I heard the wild geese. I mean, I just started out to do this for this friend and show her the effect of the line end is, you’ve said something definite. It’s very different from enjambment, and I love all that difference. And that’s what I was doing.

Tippett: To your point that the mystery is in that combination of the discipline and the “convivial listening.”

Oliver: Yeah, I was trying to do a certain kind of a construction. Nevertheless, once I started writing the poem, it was the poem, and I knew the construction well enough so that I didn’t have to think about, Do I need an end-stopped line here? Or is this where I should — it just worked itself out the way I wanted, for the exercise.

Tippett: Would you read that one? [laughs]

Oliver: [laughs] Sure. That’s kind of a secret, but it’s the truth. “Wild Geese” — I actually thought it was — oh no, there it is, 14. You’re right.

“Wild Geese” — “You do not have to be good. / You do not have to walk on your knees / for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting. / You only have to let the soft animal of your body / love what it loves. / Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine. / Meanwhile the world goes on. / Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain / are moving across the landscapes, / over the prairies and the deep trees, / the mountains and the rivers. / Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air, / are heading home again. / Whoever you are, no matter how lonely, / the world offers itself to your imagination, / calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting — / over and over announcing your place / in the family of things.”

Well, it’s a subject I knew well — a lot about.

Tippett: It was just there in you.

Oliver: It what?

Tippett: It was there in you to come out.

Oliver: It was there in me, yes. Once I heard those geese and said that line about anguish — and where that came from, I don’t know. I’d say that’s one of the poems that —

Tippett: That just came?

Oliver: Yeah. It wasn’t “dictated,” but — that’s what Blake used to say, and that’s just a way of saying you don’t know where it comes from. But if you’ve done it lot — and lord knows, when I started writing poetry, it was rotten.

Tippett: The poetry was rotten?

Oliver: Sure. I mean, I was 10, 11, 12 years old. But I kept at it, kept at it, kept at it. I used to say, with my pencil I’ve traveled to the moon and back, probably a few times. I kept at it, every day. And finally, you learn things.

Tippett: I’m conscious that I want to move towards a close. I’d like to hear a little bit more — you’ve mentioned Rumi a few times. In A Thousand Mornings, you say, “If I were a Sufi for sure I would be one of the spinning kind.” And that’s clear. I mean, actually, it makes so much sense from how you were always on the move, even as a teenager.

How do you think your spiritual sensibility — and here we are again, with that tricky word. But how has your spiritual — I don’t want to say how has your spiritual life — I mean, you’ve said somewhere, you’ve become more spiritual as you’ve grown older. And I mean, what do you mean when you say that? What’s the content of that?

Oliver: I’ve become kinder, more people-oriented, more willing to grow old. I always was investigative, in terms of everlasting life, but a little more interested now, a little more content with my answers.

Tippett: There’s this poem, the second poem in A Thousand Mornings, which is your 2013 book, which also to me just kind of says it all: What’s the point of — “I Happened to Be Standing.” Would you read that one?

Oliver: Oh yeah.

Tippett: Which is just — there it is. [laughs]

Oliver: “I don’t know where prayers go, / or what they do. / Do cats pray, while they sleep / half-asleep in the sun? / Does the opossum pray as it / crosses the street? / The sunflowers? The old black oak / growing older every year? / I know I can walk through the world, / along the shore or under the trees, / with my mind filled with things / of little importance, in full / self-attendance. A condition I can’t really / call being alive. / Is a prayer a gift, or a petition, / or does it matter? / The sunflowers blaze, maybe that’s their way. / Maybe the cats are sound asleep. Maybe not. / While I was thinking this I happened to be standing / just outside my door, with my notebook open, / which is the way I begin every morning. / Then a wren in the privet began to sing. / He was positively drenched in enthusiasm, / I don’t know why. And yet, why not. / I wouldn’t persuade you from whatever you believe / or whatever you don’t. That’s your business. / But I thought, of the wren’s singing, what could this be / if it isn’t a prayer? / So I just listened, my pen in the air.”

Well, the poems keep coming.

Tippett: [laughs] In the Poetry Handbook, you wrote, “Poetry is a life-cherishing force. And it requires a vision — a faith, to use an old-fashioned term. Yes, indeed. For poems are not words, after all, but fires for the cold, ropes let down to the lost, something as necessary as bread in the pockets of the hungry. Yes, indeed.” And I just wanted to read that back to you, because I feel like you’ve given that to so many people. You’ve demonstrated that.

And you also write in poetry about thinking of Schubert scribbling on a cafe napkin: “Thank you. Thank you.” And I feel like so many people, when they read — when they imagine you, standing outdoors with your notebook and pen in hand: Thank you, thank you.

Oliver: You’re welcome.

Tippett: It’s been a beautiful conversation.

Oliver: You are much welcome.

I’m free! I’m free!

Tippett: [laughs] Yes, you are!

[music: “Morrison County” by Craig D”Andrea]

Mary Oliver’s many honors included the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. She published over 25 books of poetry and prose, including Dream Work, A Thousand Mornings, and a collection of her poems over 50 years, called Devotions. Mary Oliver died in 2019.

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Gautam Srikishan, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Matt Martinez, and Amy Chatelaine.

Special thanks this week to Ann Godoff and Liz Calamari at Penguin Press, and to Regula Noetzli at the Charlotte Sheedy Literary Agency.

[“Cirrus” by Bonobo]

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org;

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org;

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives;

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.