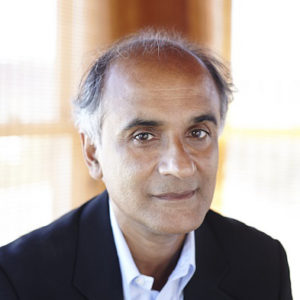

Pico Iyer

The Urgency of Slowing Down

Pico Iyer is one of our most eloquent explorers of what he calls the “inner world” — in himself and in the 21st century world at large. The journalist and novelist travels the globe from Ethiopia to North Korea and lives in Japan. But he also experiences a remote Benedictine hermitage as his second home, retreating there many times each year. In this intimate conversation, we explore the discoveries he’s making and his practice of “the art of stillness.”

Guest

Pico Iyer is the author of many books, including The Global Soul: Jet Lag, Shopping Malls, and the Search for Home, The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, and The Art of Stillness: Adventures in Going Nowhere. His latest is A Beginner's Guide to Japan: Observations and Provocations.

Transcript

This episode originally aired on June 4, 2015.

Krista Tippett, host: Pico Iyer is not a spiritual teacher or even, he says, a spiritual person per se. But he has become one of our most beloved and eloquent translators of the modern rediscovery of inner life. As a journalist and novelist, he travels the globe from Ethiopia to North Korea, and he lives in Japan. But he also experiences a remote Benedictine hermitage as his second home, retreating there many times each year. In this intimate conversation, we explore the “art of stillness” he practices — not in order to enrich the mountaintop, he writes, “but to bring calm into the motion of the world.”

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

Pico Iyer: I got out of my car at this monastery, and the air was pulsing. It was very silent, but really the silence wasn’t the absence of noise. It was almost the presence of these transparent walls that I think the monks had worked very, very hard to make available to us in the world. And somehow, almost immediately, it was as if a huge heaviness fell away from me, and the lens cap came off my eyes. Almost instantaneously I felt I’ve stepped into a richer, deeper life, a real life that I’d half-forgotten had existed.

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Pico Iyer studied at Eton, Oxford, and Harvard. He had an early successful career as a journalist with TIME magazine in New York City. But he left and moved to Japan to create a modest, quiet, nearly technology-free life. Among his many books, he’s explored the literary icon Graham Greene and authored what I think is the most searching and intimate existing portrait of the Dalai Lama. Pico Iyer still lives in Japan with his wife when he’s not on the road chronicling what he calls the “global soul.” We spoke in 2015.

Ms. Tippett: You have such an interesting background. Your parents were from India. You were born and grew up in England and the U.S. Your father was a philosopher, and your mother was also thinking about philosophy and religion. I was really intrigued to learn that your first name, which you don’t use in your writing, is Siddharth, which is based in part on the Buddha’s first name.

Mr. Iyer: Exactly. Of course, I didn’t realize until well into my 40s that I have the sort of perfect global name and the name that has fit my destiny because, as you say, my first name is the name of the Buddha. My second name, Pico — my parents, as philosophers, named me after the great Renaissance Catholic heretic Pico della Mirandola from Italy. My third name is my father’s name, Raghavan, which is a good Hindu name. And my fourth name sort of shows that I come from a lineage of south Indian priests. My father was a Theosophist, so in my four names, I have four religious traditions.

Ms. Tippett: It’s wonderful. How would you describe, if you would describe, the spiritual sensibility that you absorbed in your early life with your parents?

Mr. Iyer: I would say it was very diverse. Like any child, I didn’t appreciate it at the time, not until much later. Both my parents were teaching philosophy at Oxford University when I was a little boy, and so I would come back from kindergarten, and there would be Tibetan monks in the room, sent by the Dalai Lama to learn Western philosophy from my Indian father to complement the Tibetan philosophy they had learned. There were all the great myths and enchantments of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata and the Indian stories that my parents passed on to me at bedtime.

The other aspect was that both my parents had grown up in British India in Bombay, and so they were steeped in Shakespeare, English poetry, and the Bible. In fact, to this day, my 83-year-old mother lives in the hills of California. She always dresses in a sari, and when occasionally a missionary will pay a visit to her house and say, “Excuse me, ma’am. Have you ever read the Bible?” My sari-clad mother can recite the Bible backwards and forwards. She knows it better than anyone I’ve ever met. Later I realized what a blessing to grow up in the midst of all these traditions.

Ms. Tippett: Yes, and I think you know what I’m describing when I say that you are an intellectual. You were always an intellectual. There’s one place in your writing where you refer to “all the institutions of higher skepticism” to which your father had sent you. That’s also very defining. I wonder if you were always interested in what you now refer to as the “inner world.” What I mean by that is, did you take it seriously as an intellectual?

Mr. Iyer: I’ve got to confess to you, I think of intellectual — my prejudice is almost to think of it as a bad word or a dirty word. I think that everything important in my life has not come through my mind but through my spirit or my being or my heart. Everything I trust, whether it’s the people I love or the values I cherish or the places that have moved me have come at some much deeper level than the mind. I sometimes think the mind makes lots of complications over what is a much more beautiful and transparent encounter with the world. So I suppose I’ve tried to run away from everything I associate with the intellect. I’m very grateful for the great institutions which trained me a lot and, in fact, in some ways, enabled me to do without them and to get rid of them. I think you have to explore that world before you can turn your back on it or close the door on it. But, really, I hope the heart of my last 30 years as an adult has been about moving towards those things I can’t explain and that reason can’t begin to do justice to.

Ms. Tippett: I feel like, as an essayist and as a travel writer, as a novelist as well, you kind of are a cartographer, an observer, as well as a participant in the rediscovery of the inner world, both in yourself but also in the world at large. It runs all the way through your writing, finding people everywhere in unexpected places, exploring this part of life with a new kind of vigor and a new integrity.

Mr. Iyer: Well, thank you so much. That is a great compliment, and I will accept that, even if I don’t accept “intellectual.” [laughs] You’re right. I think it’s quite conscious in me that as a little boy, as you said, I grew up traveling a lot because — first being born to Indian parents in England, and then we moved to California when I was seven. In those days, it was actually cheaper to continue getting my education in England and flying back to my parents in the holidays than to go to the local private schools. So from the time I was nine, I was living on planes and flying across the North Pole to school by myself. Then when I was loosed upon the world in my 20s, I quickly, literally tried to map the world and to see as many places as possible and tried to take in — I always remembered that I felt I was almost a part of the first generation ever to be able to wake up one morning and to be in Tibet or Bolivia or Yemen the next day. My grandparents couldn’t have imagined that. I thought, this is an opportunity I don’t want to squander. So I traveled a lot.

Ms. Tippett: It’s one of the things that’s worth pausing every once in a while and taking in, isn’t it? No one ever says that, but it’s so true, this huge, dramatic change in our lifetime.

Mr. Iyer: Yes, which we quickly take for granted, and also the dramatic change that goes with it: that my grandparents almost had their home in their community and their tribe and their religion handed to them at birth, whereas I felt that I could, in some ways, create my own, which is a challenge, but it was a beautiful opportunity. At some point, I thought, well, I’ve been really lucky to see many, many places. Now, the great adventure is the inner world, that I’ve spent a lot of time gathering emotions, impressions, and experiences. Now, I just want to sit still for years on end, really charting that inner landscape because I think anybody who travels knows that you’re not really doing so in order to move around. You’re traveling in order to be moved. Really what you’re seeing is not just the Grand Canyon or the Great Wall but some moods or intimations or places inside yourself that you never ordinarily see when you’re sleepwalking through your daily life. I thought, there’s this great undiscovered terrain that Henry David Thoreau and Thomas Merton and Emily Dickinson fearlessly investigated, and I want to follow in their footsteps.

Ms. Tippett: Yes, and I feel like those kinds of figures who have investigated this fearlessly across the ages have been your companions. The language you just used, that we’re the first generation to create our own place in the world and be where we want to be — we’re also, and I think you’re part of this, and I guess I’m part of this too — this is the first generation where human beings don’t inherit their religious identity, their spiritual identity, where modern people are actually crafting these things on their own. I think about that too as something so new.

Mr. Iyer: Yes, we’re really on uncharted ground in that regard. That was just what I was thinking as I was saying that, that on the one hand I was lucky to be the beneficiary of, maybe, four religious traditions when I was growing up. On the other hand, I didn’t have one. To some extent, perhaps my whole life is going to be about making some kind of rigorous, useful collage of the many traditions I’ve been lucky enough to be exposed to and seeing how each can shed light on the other. But I don’t have the radiant clarity and certainty of many people whom I admire, who were born into a tradition and know from the first day that that is where they belong.

Ms. Tippett: I find it very interesting that you have really devoted yourself to this subject of the inner world, inner life, spiritual life. But you’ve repeatedly written that you have never been tempted to take up formal spiritual practices yourself, that you don’t meditate, you don’t attend services. Is that still true — even writing a book about the Dalai Lama — that you haven’t tried meditation?

Mr. Iyer: It’s embarrassing, but it’s true. [laughs] My wife wakes up every morning at 5:00 a.m. and meditates, and I lie in bed, watch her meditating, and then collapse in a heap. I do it vicariously through her. But you mentioned the Dalai Lama, and I think that’s part — I’ve been lucky enough to know the Dalai Lama since I was a teenager, and I travel with him across Japan every year. And I think spending a lot of time with a man of that degree of spiritual seriousness and devotion has taught me what a serious, solemn undertaking it is. I don’t want to be presumptuous and to claim to a religious tradition until I’ve earned it. And I think seeing somebody like the Dalai Lama or even the sometimes Zen monk Leonard Cohen, I see what hard work it is and how many years go into their feeling worthy of calling themselves a Buddhist in those instances. My Catholic monk friends teach me the same lesson.

As you know, the Dalai Lama, in response to the global times that you and I have been discussing, when he comes to this country, will always tell people, “Please don’t become a Buddhist. Stay within your own traditions where your roots are deepest. You can learn some things from Buddhists. Buddhists can learn something from you. But don’t too hastily abandon the centuries of tradition set under you and grab something you perhaps imperfectly understand. I think he brings us back to that wonderful truth, which is also maybe a feature of this age, which is that when a Buddhist and a Christian have a really deep conversation, the Buddhist becomes a better Buddhist, and the Christian becomes a better Christian. I think that’s what’s been happening in the last 25 years that is probably enriching all our traditions.

Just while I think of it, when you asked me, as so many of my friends do, why I don’t meditate — if my wife were here, she would fall around laughing and say, “Krista, all this guy ever does is meditate.” Just because I’m a writer. She sees me — I wake up, I have breakfast, I make a five-foot commute to my desk, and then I just sit there for at least five hours trying to sift through my distortions and illusions and projections and find what is real behind the many things I’m tempted to say. And I think a writer is in the blessed position because, in some ways, our job is to sit still and to meditate for a living. So although I don’t have a formal spiritual meditation practice, I do spend much of my life in the middle of nowhere, stationary. I’m really grateful for that.

[music: “Early In The Park” by Hauschka]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today with essayist, novelist, and travel writer Pico Iyer.

Ms. Tippett: You’ve given a name to this life you lead, to what I would call a contemplative practice, which is stillness. I think it’s such a wonderful way that you’ve injected that word in your writing and into our cultural discourse. I wonder, can you trace when you started to use that word, to name this impulse in you in that way?

Mr. Iyer: I think I can very distinctly. As I said, I’ve always traveled a lot, and even in my 30s, I noticed I’d already accumulated one million miles on a single United States airline. So I realized I have a lot of movement in my life, but not maybe enough stillness. Around that same time, our family house in Santa Barbara burned to the ground, and I lost everything I had in the world. I bought a toothbrush from an all-night supermarket that evening, and that was the only thing I had the next day. So I was unusually footloose. A friend who was a school teacher recommended that I go and spend a few days in a Catholic hermitage. Although I am not Catholic, and although I am not a hermit, he told me that he always took his classes there and even the most distracted, restless, testosterone-addled adolescent boy felt calmer and clearer when he went there. I thought, anything that works for an adolescent boy ought to work for me.

I got in my car, and I drove north along the coast following the sea. The road got narrower and narrower, and then I came to an even narrower, barely paved road that snaked up for two miles to the top of a mountain. I got out of my car at this monastery, and the air was pulsing. It was very silent, but really the silence wasn’t the absence of noise. It was almost the presence of these transparent walls that I think the monks had worked very, very hard to make available to us in the world. I stepped into the little room where I was going to stay, and it was simple. There was a bed and a long desk, and above the desk a long picture window, and outside it a walled garden with a chair, and beyond that just this great blue expanse of the Pacific Ocean. Somehow, almost immediately, it was as if a huge heaviness fell away from me, and the lens cap came off my eyes. Suddenly, I was seeing everything with great immediacy, and it was almost as if little Pico had disappeared, and the whole world had come in to me instead. I remember a blue jay suddenly alighted on the fence outside my window, and I watched it, rapt, as if it was the most miraculous thing that had happened. Then bells began ringing above, and it felt like they were ringing inside me. Then when darkness fell, I just walked along the monastery road under the stars, watching the taillights of cars disappear around the headlands to the south. And really, almost instantaneously, I felt I’ve stepped into a richer, deeper life, a real life that I had half-forgotten had existed.

One thing I noticed was, when I was driving up, like many of us, I was conducting all kinds of conversations or arguments in my head. I was feeling guilty about leaving my mother behind, and I was worried that my bosses wouldn’t be able to find me for three days. As soon as I arrived in that place, I realized that none of that mattered and that, really, by being here, I would have so much more to offer my mother and my friends and my bosses.

The last thing I’ll say about this is that nowadays when I visit my mother — she lives in the hills of California at exactly the same elevation as the monastery, 1200 feet, and she enjoys a beautiful view over the Pacific Ocean. To anybody looking at her house, they would say it’s the last word in tranquility and seclusion. But of course, when I’m at home, if ever I’m tempted to read a book, a part of me is braced for the phone to ring or the chime of “you’ve got mail” in the next room. I interrupt myself, even if it doesn’t interrupt me. And if ever I’m tempted to look at the stars, I think, oh no, there are a thousand things I have to do around the house or around the town. Or if I’m involved in a deep conversation, I think, oh, the Lakers game is on T.V. I should do that. So one way or another, I always cut into my own clarity and concentration when I’m at home. It reminded me why sometimes people like me have to take conscious measures to step into the stillness and silence and be reminded of how it washes us clean, really.

Ms. Tippett: Was that the same Benedictine hermitage that you go to now, that you spend time at every year?

Mr. Iyer: Absolutely. I’ve been going now for 24 years, I’ve stayed there more than 70 times. I really think that’s my secret home. In a world of change and sometimes impermanence that, along with my wife and my mother, are really the still point of my world. Wherever I’m traveling in the world, I have the image of that little room with the Pacific below it in my head and the chapel there too. I feel that really steadies and grounds me in the way I need in a world of tumult.

Ms. Tippett: I think that’s such an important point because as you pursued that place of stillness that you found both physically and inside yourself, it seems to me you’ve held that in a creative tension with moving back out into the world and with movement. Here’s something beautiful you wrote: “The point of gathering stillness is not to enrich the sanctuary or the mountaintop, but to bring that calm into the motion, the commotion of the world.”

We haven’t used the word “spirituality” yet. You make the same connection when you write explicitly about spirituality, that it arises out of the disjunction between us and the transcendent. Spirituality is in some kind of tension with stillness, right? That, in fact, this is the place where we meet our demons as well. I feel like that’s there in your writing.

Mr. Iyer: Beautiful. I absolutely agree with that. Sometimes “mystery” is a word I use as an equivalent to spirituality. You’re right. I think our relation with the Divine is a love affair. It’s a passionate love affair. It’s also as tumultuous as any affair that we have in the world with somebody we care about a lot. So it’s not all sweetness and light and probably shouldn’t be because the sufferings and the demons are often what instructs us much more than the calm, radiant moments.

I love people like Thomas Merton because half the time he’s in his hermitage. He’s chafing against it. He’s knocking against the walls. He’s longing to be out in the world, and he’s honest enough to say that, as you said, the electricity comes in the tension and that there’s no sense of light without a darkness and without a dark night of the soul.

I once spent some time in Iceland in the middle of the summer when the sun doesn’t set for 90 days and nights, so it’s always light out. It was very disorienting. I had lost all sense of when to eat, when to sleep, when to dream. It was a tiny physical reminder that we need that cycle of light and dark.

Ms. Tippett: That so nuances the kind of simplified characterizations that we sometimes have about religion. I agree with you that theology and spiritual practice and religious traditions are all about the complexity of the human condition. But that doesn’t find expression so much in popular culture. A couple of years ago, after you published your book about Graham Greene, I went to a conversation you had with Paul Holdengräber at the New York Public Library. Do you remember that?

Mr. Iyer: I do. I wish I had known you were there. But yes, I remember it well.

Ms. Tippett: I was there, because I had started reading you, and you said something that night that I have, all these years, been looking forward to the day when I would be able to discuss it with you. [laughs] I think Paul may have asked you the question that is always out there: What is the difference between spirituality and religion? And I believe you said this — that spirituality is water, and religion is the tea. I wondered, what if spirituality is water, and religion is the cup, which carries it forward, although it may be flawed, and we may drop it and break it. I don’t know, what do you think about that?

Mr. Iyer: I love that notion of the cup. If you had just asked me that question now, I would say that spirituality is, as we were just saying, the story of our passionate affair with what is deepest inside us and with the candle that’s always flickering inside us and sometimes almost seems to go out and sometimes blazes. And religion is the community, the framework, the tradition, all the other people into which we bring what we find in solitude. In some ways, I would say very much exactly the thing that you just said.

I should also say, if I talked about water and tea, I was probably stealing from the Dalai Lama, because he will often say that the most important thing without which we can’t live is kindness. We need that to survive. He says, kindness is water, religion is like tea. It’s a great luxury. It increases the savor of life. It’s wonderful if you have it. But you can survive without tea. You can’t survive without water. Everyday kindness and responsibility is the starting block for every life. So I might have been alluding to him there. It’s a nice reminder to ground ourselves in the people around us before we start thinking about our texts and our notions of the absolute.

[music: “Baleen Morning” by Balmorhea]

Ms. Tippett: It’s so interesting to me, thinking about you going and being with those Benedictines year after year and how, in fact, that’s an experience so many people are having now. I grew up Protestant, and I think the monastics were — it’s not something I knew about, and when I learned about it as I grew older, it baffled me. I remember somebody explaining to me that the people who gave themselves over to monastic existence are devoting themselves to prayer and contemplation on behalf of all of us. I thought that was a beautiful idea, and I held that, and I honored that for many years. It’s interesting that now, as so many 21st-century people are finding refuge and also a kind of grounding in these monasteries, there’s a depth of reality to that idea that they are praying and being contemplative on behalf of all of us, keeping the doors open to these places where that can happen.

Mr. Iyer: I’m as fascinated by them as I am by the men who can take my car when it stops moving and magically put it together again. But of course, when we think of monasteries, it gets back to what you and I were just discussing, which is, as you say, more and more people are doing what I do, which is going on retreat and wanting to recollect themselves and replenish themselves and to draw from the energy and inspiration of the monks. But fewer and fewer are ready to make a long-term commitment. I think that’s a sad challenge of the age, that we’re getting what we can from it, but we’re not really surrendering to it absolutely in the way that would really be the most meaningful and fruitful for us.

Ms. Tippett: You also write about the idea of Nowhere. Nowhere with a capital “N.” [laughs] Where is that, that Nowhere with a capital “N,” and what does it mean?

Mr. Iyer: It’s probably the wilderness, and the wilderness is probably the place where one finds illumination. But the reason I came up with that funny formulation is that I noticed when I began traveling a lot 30 years ago, I would talk about going to Cuba or going to Tibet, and people’s eyes would light up with excitement. Nowadays, I notice that people’s eyes light up most in excitement when I talk about going nowhere or going offline. I think a lot of us have this sense that we’re living at the speed of light, at a pace determined by machines, and we’ve lost the ability to live at the speed of life.

Ms. Tippett: Right. That’s good. Well, we are analog creatures. Here’s a way you said it in The Guardian: “We have more information and less space to make sense of it.” It’s not just the pace, but the room to make meaning as well as just be processing or getting through our to-do lists.

Mr. Iyer: Exactly. Whoever you are, whether you’re a mother raising kids or somebody going to the office, you know that, really, as you said, you’re extracting the meaning only when you’re away from it. I sometimes think we’re living so close to our lives, we can’t make sense of them. That’s why people like me go on retreat, or other people meditate or do yoga, or other people go for runs. Each person, I think, now has to take a conscious measure to separate herself from experience just to be able to do justice to experience and to process, as you said, and understand what is going on in her life and direct herself.

Ms. Tippett: We’ve spoken about your notion of stillness, and that’s one way you describe your practice. One way you talk about that — a Buddhist corollary is this notion of “right absorption.” I really like that, and I think that also applies to what you just described: a discipline and maybe even a necessity for all of us in whatever kind of life we lead.

Mr. Iyer: Yes, I love that word “absorption” because I think that’s my definition of happiness. I think all of us know we are happiest when we forget ourselves, when we forget the time, when we lose ourselves in a beautiful piece of music or a movie or a deep conversation with a friend or an intimate encounter with someone we love. That’s our definition of happiness. Very few people feel happy racing from one text to the next to the appointment to the cell phone to the emails. If people are happy like that, that’s great. I think a lot of us have got caught up in this cycle that we don’t know how to stop and isn’t sustaining us in the deepest way. And I think we all know our outer lives are only as good as our inner lives. So to neglect our inner lives is really to incapacitate our outer lives. We don’t have so much to give to other people or the world or our job or our kids.

[music: “Twinkle” by Victor Malloy]

Ms. Tippett: After a short break, more with Pico Iyer. You can subscribe to On Being on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, or Spotify to listen again and discover produced and unedited versions of everything we do.

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, exploring the “art of stillness” with essayist, novelist, and travel writer Pico Iyer. He began his career as a journalist with TIME magazine. He’s now based in a modest, quiet, nearly technology-free home in Japan. He’s written many books and is still often to be found in the pages of publications like The New York Times and The Guardian. But he also retreats many times each year to a Benedictine hermitage in Big Sur, California. He’s one of our most eloquent translators of 21st-century people’s rediscovery of inner life.

Ms. Tippett: One interesting thing you’ve said about living in Japan, in fact, is that it’s made you aware of time in a new way. I want to go back because in your 20s, you left your very successful, exciting life in New York, and I think you left to live for a year in a temple in Kyoto, but you didn’t end up staying for a year. Is that right?

Mr. Iyer: Exactly right. [laughs] I stayed for a week, by which time I found a temple in Kyoto is very different from what I’d imagined in midtown Manhattan. But I did move then to a single room on the back streets of Kyoto without even a toilet or a telephone or a bed.

Ms. Tippett: All right, then. You’re absolved. [laughs] Tell me what you learned about time. And perhaps this is still true, because you spend most of your life in Japan now. I’m so intrigued because I think time is just such a fascinating concept, and it has all this resonance both in science and in mysticism.

Mr. Iyer: Yes, and I think we all know that sensation. We have more and more time-saving devices but less and less time, it seems to us. When I was a boy, the sense of luxury had to do with a lot of space, maybe having a big house or a huge car. Now I think luxury has to do with having a lot of time. The ultimate luxury now might be just a blank space in the calendar. And interestingly enough, that’s what we crave, I think, so many of us.

When I moved from New York City to rural Japan — after my year in Kyoto, I essentially moved to a two-room apartment, which is where I still live with my wife and, formerly, our two kids. We don’t have a car or a bicycle or a T.V. I can understand. It’s very simple, but it feels very luxurious. One reason is that when I wake up, it seems as if the whole day stretches in front of me like an enormous meadow, which is never a sensation I had when I was in go-go New York City. I can spend five hours at my desk. And then I can take a walk. And then I can spend one hour reading a book where, as I read, I can feel myself getting deeper and more attentive and more nuanced. It’s like a wonderful conversation.

Then I have a chance to take another walk around the neighborhood and take care of my emails and keep my bosses at bay and then go and play ping pong and then spend the evening with my wife. It seems as if the day has a thousand hours, and that’s exactly what I tend not to experience or feel when I’m — for example, today in Los Angeles — moving from place to place. I suppose it’s a trade-off. I gave up financial security, and I gave up the excitements of the big city. But I thought it was worth it in order to have two things, freedom and time. The biggest luxury I enjoy when I’m in Japan is, as soon as I arrive there, I take off my watch, and I feel I never need to put it on again. I can soon begin to tell the time by how the light is slanting off our walls at sunrise and when the darkness falls — and I suppose back to a more essential human life.

Ms. Tippett: That’s about the life you’ve crafted, rather than something in Japanese culture, right?

Mr. Iyer: It is, but of course, when I left New York City, I could have gone anywhere. As a writer, I’m lucky; I could do my job anywhere. I think one reason I went to Japan — it goes back to what you were asking about the institutes of higher skepticism — is that my education had taught me quite well to talk, but I don’t think it had taught me to listen. My schools had taught me quite well to push myself forward in the world, but it never taught me to erase myself. The virtues of when I got to Japan, finding that I was essentially an illiterate — to this day, I can’t read or write Japanese. I’m at the mercy of things around me. I can’t have the illusion that I’m on top of things. Japan was a place that I had a huge amount to learn from, and I’m still learning it.

Ms. Tippett: You’ve talked about that we are rediscovering — I really love this phrase — the “urgency of slowing down.” That’s wonderful.

Mr. Iyer: Thank you. Well, I think we’re all feeling dizzy. We got onto this accelerating roller coaster that we never quite asked to get on, and we don’t know how to get off. My keenest sense is that our devices are not going to go away, nor would we want them to. They’ve made our lives so much brighter and healthier and longer. But it’s a safe bet that they’re only going to accelerate and proliferate. We’re really going to have to take emergency measures just to keep ourselves in proportion and in balance. I sometimes think that travel is how I get my excitement and stimulation, but stillness is how I keep myself sane. Pascal, wonderfully, in the 17th century, said, our problem is distraction. But we try to distract ourselves from distractions, so we get even worse in this vicious cycle.

So the only cure for distraction is attention. I go to my monastery and I go to Japan because they are cathedrals of attention. They’re places where people are very attentive and where people like me can try to learn attention.

Ms. Tippett: I couldn’t help wondering as I’m reading you and reading about the life you’ve crafted, you really have chosen a simplicity that — I think you even use the word “luxurious.” You talk about being with Leonard Cohen, and he uses the word “luxurious” — and in such a contrast to the you at 29, living the American dream. But I couldn’t help wondering how much of what you’ve been able to choose and create also is about the wisdom that comes just with growing older, with age, that stillness becomes more natural and more enjoyable somehow, I think, inherently. I’m not sure everyone leans into that. In fact, I know they don’t.

I was reading recently that there’s some new study that when we’re young, we’re hardwired to find excitement and to find satisfaction in novelty, and that as we age, we more naturally find excitement and satisfaction in what is ordinary, in patterns and habits and the everyday contours of our lives. It helps me think about why wisdom comes with age, why an elder becomes an elder because what becomes more natural is really getting at the deepest insights of spiritual traditions.

Mr. Iyer: Yes. I was just saying to somebody yesterday that, at some point — I’m only, I think, a couple of years older than you — I noticed that I was getting so much more satisfaction from visiting my old friends than looking around for new friends; and rereading the books I’ve always loved, which each time were giving me new and new things rather than trying to find the latest good book; and revisiting the places with which I have a relationship over 30 or 50 years. Instantly you don’t have to explain yourself. You’re doing without the excitement of novelty, but you’re into a much deeper and more intimate encounter. You’re right that soon that becomes much more sustaining than just getting the new. Of course, the older you get, the harder it is to be confronted with something new, which is why, probably, time accelerates, and it seems like the years are whizzing by like the calendar pages in one of those old movies.

I think the other thing that I suppose I learned from Leonard Cohen was, when I met him, he was living for a monk for five years in the cold, dark mountains behind Los Angeles, and he said, as you mentioned, that sitting still and looking after other people and scrubbing floors was a great voluptuous excitement of life, even though he’d enjoyed all the pleasures of the world. But the second part of that process, which maybe is even more important, is, again, he came back into the world. He’s toured the world in his 70s for six years and became one of the most popular musicians on the planet. I think the reason he became popular was that people could tell he was coming down from the mountain, in a way. In other words, he was bringing wisdom and depth and selflessness to the concert stage, just where we don’t usually see it. And I think, even if they couldn’t articulate it, people felt that they were getting something of the stillness and pointedness of the monastery from him, not just another kind of agenda or somebody trying to sell something.

[music: “Cyclone” by MONO]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, exploring the “art of stillness” with writer Pico Iyer.

Ms. Tippett: We’re winding down towards the end, but I do want to ask you about mysticism. I want to read something you wrote. It intrigued me: “Mysticism, to me, is what stands out of time and beyond circumstance. Read a 13th-century Zen discourse, pick up St. John of the cross, and listen to the latest Leonard Cohen album, and you are instantly in the same place. Mysticism is almost the unchanging backbeat and backstage truth that stands behind all the changing surfaces and shifts in the world.”

Mr. Iyer: My heavens, I actually like that. [laughs] I still believe it.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] Does mysticism have a different role or a new role or an expansive role in a globalized world, in the 21st-century world?

Mr. Iyer: I think in an accelerated world it does, because I think we need, more than ever, to root ourselves in what is out of time and larger than us and not contained in the latest CNN update. It’s wonderful to know what happened two seconds ago at the Grammys or, even more important, in Iraq. But we can’t begin to make sense of it unless we have a larger, more spacious canvas on which to put it. In that sense, it’s funny — when you just read that description of mysticism, it sounds exactly like my description of my hermitage. I think I was probably using those as almost interchangeable terms there. But if mysticism is a word for that place where we are deeper and wiser than ourselves, or at least can listen to something inside ourselves that seems much larger than we are, we certainly need that more than ever because I would imagine in the 19th century, say, when there are far fewer obvious diversions, maybe it’s a romantic notion, but I imagine people being able to hear the better part of themselves a little more often.

It’s hard to hear in the clamor of the contemporary, and I notice people more and more talk about cutting through the noise. That’s what we really need to do. I suppose mysticism is a way of cutting through the cacophony of the moment and reminding us of what is real and then reminding us of how to respond to the real and to do justice to it.

Maybe that speaks to the other part of your question, which is the beauty of mysticism is it’s the place where distinctions dissolve and where there’s no you and me, there’s no east and west, there’s no old or new. We’re in the place beyond dualisms and beyond the tricks of the mind, really, to go back to your point about being an intellectual. We are in that space where we’re not outside the world making judgments and distinctions. We are in some truth, which we don’t even have to name, but it’s the place where all those great traditions converge. So if Rumi and John of the Cross and Meister Eckhart and Dōgen, the great Zen teacher, were to talk together, each might talk in the language and in the framework of his particular tradition, but what they’d be talking about is something each of them would recognize as his most intimate reality.

Ms. Tippett: And none of their words would reach quite far enough, right?

Mr. Iyer: Exactly. Mysticism is the place where all words, explanations run out.

Ms. Tippett: I rarely see you speaking of God, and I really feel like what you just said is so eloquent. And, certainly, God is one of those realities we can only point at with words. I don’t know, do you have a sense of God, or is that language you avoid, or is it just that I haven’t seen it?

Mr. Iyer: You’re right. It is language I avoid. I remember, as a little boy, whenever I saw something in capital letters, something in me would recoil. But oddly enough, somebody two weeks ago suddenly, out of nowhere, asked me, “What is God?” And I said, “Reality.”

I think that has many ramifications. But usually, what I would say is that I would certainly use the word the divine as you and I have used earlier in this discussion. I think we all have something changeless and vast and completely unfathomable inside us. I’m very happy if a Christian calls that God and if a Muslim calls that Allah and if a Buddhist calls that reality or something else. Again, I don’t think that the names matter so much, but the truth is very, very important, and I think that’s the fundamental truth that we can’t afford to lose sight of.

When you talked earlier on about my seeking out spiritual places and people, I suppose it’s because at a very early age I noticed that I didn’t have one fixed religion myself, that people who did have a religious commitment seemed to be acting with such kindness and such selflessness and such clarity that I thought, these are people I want to learn from. What I was learning from them was that they were listening to God and, even more importantly sometimes, obeying God, and obeying God when God is asking them impossible things. But still, they knew that that was where their commitment lay. I can’t begin to say how much appreciation and admiration I have for those who have made God the center of their lives, or in the case of the Dalai Lama, he might say reality is the center of his life, but it’s a variation on the same thing.

Ms. Tippett: You do lead this very simple life, but you write books that people read. A couple of times in recent years, you’ve had pieces in the The New York Times, and there’s one you wrote a couple of years ago, maybe while you were writing your book on stillness. Was it called “The Joy of Quiet”? Is that right?

Mr. Iyer: Yes.

Ms. Tippett: You ended with — you were at your monastery, your secret home, as you say, in California, I believe. You talked about — out walking, speaking to someone who works at MTV, brings his young children there, so he’s introducing them to the joy of quiet. You had a line that just stayed with me at the end. You wrote, “The child of tomorrow, I realized, may actually be ahead of us in terms of sensing not what’s new, but what’s essential.” I just wanted to read that back to you. It’s very beautiful.

Mr. Iyer: Well, thank you for such a high compliment. The reason I ended that piece with that sentence was I’d begun the piece by describing how I was going to a conference in Singapore with the title “Marketing to the Child of Tomorrow.” So that piece is really moving from the profane to the sacred, or moving from the heart of the world, where the child of tomorrow is seen in the same sentence as marketing, to what is really going to support the child of tomorrow, which is far from the marketplace and is something more akin to stillness. In fact, I wonderfully had an editor at The New York Times who would throw these things at me and who also commissioned the TED book a couple of years ago. Out of the blue, though we had never met, she said, “Why don’t you write a piece on silence?” Then she said, “Why don’t you write a piece on anxiety?” And, “Why don’t you write a piece on suffering?” I was so glad to have the chance to talk about those things. And, as you said, I was pleasantly surprised that The New York Times would want to feature those prominently in the newspaper as the corrective to the moment.

Ms. Tippett: I do want to ask you this large question. As you have lived this life you’ve lived, how has your sense evolved of this great animating question behind our spiritual traditions but also this universal human question: What does it mean to be human?

Mr. Iyer: I think to be human really means to be connected. I’m a rather solitary soul, and I’ve talked a lot about stillness and silence, but I think that they are just way stations. They are refueling places. It’s funny, when we go to an airport nowadays, there’s so many recharging stations for devices and very few for our soul.

Ms. Tippett: Right. [laughs] All of a sudden there are all these recharging stations.

Mr. Iyer: All of a sudden. And we quickly realize it’s only when we recharge our soul, we can make better use of our devices. Part of my concern about the digital age is that the beauty of it is we can make contact with people on the far corners of the earth. The challenge is we sometimes lose contact with ourselves, especially our deeper selves. And then we’re tempted more to define ourselves in terms of what doesn’t matter and what is not going to last very long, whether it’s our looks, our finances, or our resume. And I don’t think anyone gets the richer if he or she defines herself in those terms. So I think to be human is to try to find the best part of yourself that is, in fact, beyond yourself, much wiser than you are, and have that to share with everyone you care for.

[music: “Dilate” by Wes Swing]

Ms. Tippett: Pico Iyer is the author of over a dozen books including The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, and The Art of Stillness: Adventures in Going Nowhere. He’s currently at work on two new books for 2019: Autumn Light and A Beginner’s Guide to Japan.

[music: “Akiko” by Guitar]

Staff: On Being is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Maia Tarrell, Marie Sambilay, Erinn Farrell, Laurén Dørdal, Tony Liu, Bethany Iverson, Erin Colasacco, Kristin Lin, Profit Idowu, Casper ter Kuile, Angie Thurston, Sue Phillips, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Damon Lee, Suzette Burley, Katie Gordon, and Zack Rose.

Ms. Tippett: Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing our final credits in each show is hip-hop artist Lizzo.

On Being was created at American Public Media. Our funding partners include:

The John Templeton Foundation. Supporting academic research and civil dialogue on the deepest and most perplexing questions facing humankind: Who are we? Why are we here? And where are we going? To learn more, visit templeton.org.

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, working to create a future where universal spiritual values form the foundation of how we care for our common home.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The Henry Luce Foundation, in support of Public Theology Reimagined.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Sponsors

Funding provided in part by the John Templeton Foundation. The Templeton Foundation supports research and civil dialogue on the deepest and most perplexing questions facing humankind: Who are we? Why are we here? Where are we going? To learn more, please visit templeton.org.