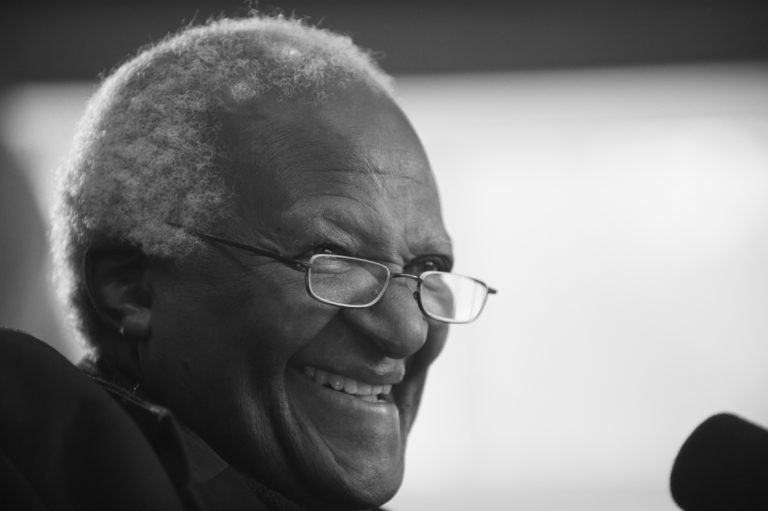

Remembering Desmond Tutu

The remarkable Archbishop Emeritus of Cape Town and Nobel Laureate died in the closing days of 2021. He helped galvanize South Africa’s improbably peaceful transition from apartheid to democracy. He was a leader in the religious drama that transfigured South African Christianity. And he continued to engage conflict well into his retirement, in his own country and in the global Anglican communion. Krista explored all of these things with him in this warm, soaring 2010 conversation — and how Desmond Tutu’s understanding of God and humanity unfolded through the history he helped to shape.

Image by Tom Gennara, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Desmond Tutu was an Anglican archbishop emeritus of Cape Town, South Africa and recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He has written numerous books for adults and children — including The Rainbow People of God, No Future without Forgiveness, Made for Goodness, and, together with his good friend the Dalai Lama, The Book of Joy.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: Archbishop Desmond Tutu died on December 26, 2021, in Cape Town, at 90 years old, and we remember him this hour. The warm and personal conversation I had with him in 2010 was one of the highlights of all my years in radio. Tutu helped galvanize South Africa’s improbably peaceful transition from apartheid to democracy. He was also a leader in the religious drama that transfigured South African Christianity. Yet he continued to face challenges well into his retirement — the ongoing inequity and violence in his country, and his own Anglican Communion becoming part of a global conflict around sexual orientation and leadership. We explored all these things in our conversation, including how Desmond Tutu’s understanding of God and humanity unfolded through the history he helped shape.

[music: “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” (South African National Anthem) by Soweto Gospel Choir]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

I interviewed Desmond Tutu in the woods of southern Michigan, where he was on retreat, just months before he announced his retirement from public life. He disarmed me from the outset with his famously mischievous humor. I’d brought along a bowl of dried mangos, having been told by his staff that he is “mad about dried mango.” And he noticed them as we were finding our seats, before I could say anything.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu: There we go. And I notice, I mean, you’ve got a glass of water; I’ve got a glass of water. But then you have dried fruit. Why do you rate dried fruit, and I not? [laughs]

Tippett: [laughs] I brought this for you, because your office told us that you love dried mango.

Tutu: Oh, you beautiful thing. Oh, you are a star. [laughs]

Can we say a prayer first?

Tippett: Yes, please.

Tutu: Come, Holy Spirit. Fill the hearts of thy faithful people and kindle in them the fire of thy love. Send forth thy spirit and they shall be made, and thou shalt renew the face of the Earth. Amen.

[music: “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” (original hymn) by Soweto Community Hall]

Tippett: This hymn of the Xhosa language, “God Bless Africa,” is the joint national anthem of modern South Africa. But when Desmond Tutu was born, in 1931, it was an anthem of the anti-government South African Native National Congress. When the Dutch Colonial Afrikaner Nationalist Party came to power in South Africa in 1948, it decreed White supremacy in perpetuity, codifying the policy of apartheid, which literally translates as “apartness.” Comprehensive separation, and brutalization, of the 80 percent majority population of non-Whites became the law of the land.

Desmond Tutu grew up, like other Black children, in a ghetto township marked by deprivation. But he stressed that his childhood was not devoid of joy; children adapt, he played with his friends. But there were many moments which he traced as early stirrings of his sense of injustice. And I wondered, when we spoke, if Desmond Tutu’s personal spirit of resistance might also have had roots in the Xhosa ancestry of his father. These were some of the earliest people to encounter and rebel against White intruders in the South African Cape some 300 years ago — the backdrop to all of the history Desmond Tutu lived through and shaped.

Tutu: You know, they recently did a genome sequencing and found that, through my mother, I’m related to the San people, who are the earliest inhabitants of southern Africa and probably some of the earliest human beings.

But I think, I mean, that the later resistance was because of various factors; the people who influenced me, the schools that I went to. At one time I worked for the World Council of Churches, and we were based in London. I came from Africa; there was someone from Latin America, and he introduced me to Latin American liberation theology. And I came to visit for the first time in the United States, and here encountered Black theology. So all of that was a very significant part of what helped to open my eyes.

Tippett: And you know, as I steeped myself in your story I was so struck by the echoes of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, theologically — both in terms of your life and theology — the echoes and the parallels. And you know, there are very strong echoes of this German theologian who eventually became involved in a plot to assassinate Hitler. And it seems like you also found yourself in a place and time where you were called to a very extreme understanding of, as the bracelet says, what Jesus would do.

Tutu: Obviously, when, as you are living your life and you have this and that influence, at the time when it happens you don’t sit back and say, Now, this is a major influence, and it’s going to turn me into this or that. But, you see, I went to train for the priesthood in a seminary that was run by a religious community. And one of my mentors was Trevor Huddleston, who was just an incredible human being. He had come from England and was a priest in Sophiatown, the Black township to the west of Johannesburg. And when the apartheid government wanted to destroy Sophiatown, he was amongst those who resisted like nobody’s business. And those are people who touched my life. And mercifully, there isn’t anything like the so-called self-made person. [laughs]

Tippett: Right. You had spiritual companions.

Tutu: Yes — they are more than that. I mean, they are people who helped to form me.

And then discovering that the Bible could be such dynamite: I subsequently used to say, if these White people had intended keeping us under, they shouldn’t have given us the Bible, because, whoa, I mean, it’s almost as if it is written specifically just for your situation. I mean, the many parts of it that were so germane, so utterly to the point for us —

Tippett: Can you recall one of those early discoveries of the Bible as dynamite, some teaching that you suddenly saw as so relevant?

Tutu: Well, actually, it’s the very first thing. When you discovered that apartheid sought to mislead people into believing that what gave value to human beings was a biological irrelevance, really — skin color or ethnicity — and you saw how the scriptures say it is because we are created in the image of God that each one of us is a God-carrier; that no matter what our physical circumstances may be, no matter how awful, no matter how deprived you could be, it doesn’t take away from you this intrinsic worth — one saw just how significant it was.

Although I was a bishop, I was working now for the Southern Council of Churches and had a small parish in Soweto. Most of my parishioners were domestic workers, not people who were very well educated. But I would say to them, “You know, mama, when they ask, Who are you” — you see, the White employer most frequently didn’t use the person’s name. They said the person’s name was too difficult. And so most Africans, women would be called “Annie,” and most Black men, really, you were “boy.” And I would say to them, When they ask, Who are you?, you say, Me? I’m a God-carrier. I’m God’s partner. I’m created in the image of God.

And you could see those dear old ladies as they walked out of church on that occasion, as if they were on cloud nine. You know, they walked with their backs slightly straighter. It was amazing.

Tippett: I think much of the world — and this has to do with my profession of journalism, as well — experienced the events in South Africa, those decades leading up to the end of apartheid, primarily as political happenings. But there was a great religious drama at the heart of it, right? So on the one hand, the church, the Dutch Reform Church, the primary church in South Africa, sanctioned and sustained apartheid to near the end. And also, as you say, there was this parallel drama going on of religion, theology, the Bible becoming a great force of liberation.

Tutu: Well, one of the wonderful things was how, in fact, we had this interfaith cooperation; Muslims, Christians, Jews, Hindus. And now, when you hear people speak about — disparagingly about, say, Islam, and you say, They’ve forgotten that that faith inspired people to great acts of courage.

Tippett: And was that building — that coalition, those friendships, were they building in those latter decades of the 20th century?

Tutu: Well, you discovered the thing you were fighting against was too big for divided churches, for divided religious community. And each of the different faith communities realized some of the very significant central teachings about the worth of a human being, about the unacceptability of injustice and oppression. Many times, actually, it was quite exhilarating. You know, it was fun. [laughs]

Tippett: [laughs] Right.

[music: “Sebai Bai” by Mohotella Queens]

And then there was that momentous occasion — I think, was it 1990 when there was the first conference in 30 years to bring together the Dutch Reform leaders with these other churches? And there was this heartfelt apology. This is the 1990s, so things had started to break open, but there was still a lot of potential for danger, right? And here’s what you said: “We have been on a kind of roller coaster ride, reaching the heights of euphoria that a new dispensation was virtually here, and then touching the depths of despair because of the mindless violence and carnage that seemed to place the whole negotiation process in considerable jeopardy. And just as we were recovering our breath, the god of surprises played his most extraordinary and incredible card.”

Tutu: [laughs] Did I say that?

Tippett: You said that. It’s beautiful. [laughs]

Tutu: [laughs] Well, I mean, God is a god of surprises. I’ve sometimes said God’s sense of humor is quite something. An illustration of the sort of craziness: they had dealt with somebody called Beyers Naude; he was an Afrikaner who at one point said, No, apartheid can’t be justified scripturally. And for this he was turfed out of his church. They expelled him because, they said, he was a traitor. And so he joined up with Blacks and others who were opposing.

When freedom came, there was a road in Johannesburg that had been named after D. F. Malan. In 1948, Malan became the first nationalist prime minister, and so they had this D. F. Malan driveway.

[laughs] In 1994–’95, the name was changed to Beyers Naude Highway. [laughs] I mean, you would almost imagine them in heaven, sort of rolling in the aisles. [laughs]

[music: “Misahotaka Ny Akama” by Rajery]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today we are revisiting my delightful conversation with Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who died in the last days of 2021.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which he chaired, met formally from 1995 to 1998. The TRC, as it was known, was conceived as apartheid unraveled in the early 1990s. Its basic premise was that any individual, whatever they had done, was eligible for amnesty if they would fully disclose and confess their crimes. The commission investigated human rights violations by both architects and opponents of apartheid. Victims were invited to tell their stories and witness confessions. Many families came to know, for the first time, when and how their loved ones had died.

[music: “Thina Sizwe” by SABC Choir]

I wonder, in the years that followed and in your experience of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, what did you learn about why, as you said, one of the hardest things for human beings to do is to say, “I’m sorry”? I mean, what did you learn about forgiveness, three-dimensionally, that you didn’t know before?

Tutu: One was, I was amazed, first of all, at how powerful an instrument it is, being able to tell your story. I suppose psychiatrists understand that better than we. Just being able to tell your story — you could see, in the number of people who for so long had been sort of just anonymous, faceless non-entities, just being given the opportunity did something to rehabilitate them.

But more than that, it actually was a healing thing. We had a young man, a Black young man who had been blinded by police action in his township, and he came to tell his story. When he finished, one of the TRC panel asked him, Hey, how do you feel? And a broad smile broke over his face. And he was still blind, but he said, You’ve given me back my eyes. And, you know, you felt so humbled that people could feel that that was how the healing for him would have taken place.

But you know, one of the things that constantly amazed us was the remarkable magnanimity of people, all people — Black, White, Africans — and Americans. I mean, human beings can leave you speechless, really. They can leave you speechless by the horrible things they do, but they also leave you speechless with the incredible things. We saw, so many times, people who ought to have been bristling with bitterness and anger, when they meet the perpetrator, actually being able to embrace.

And you were asking about the difficulty. Yes, it is difficult. And when we started, we looked at the legislation, and the legislation did not require a perpetrator who applied for amnesty to express even remorse. And we were very upset and said, But, I mean, why not say they’ve got to say sorry or something? But we discovered that actually the legislators were a lot smarter, because had they insisted that it was a condition to get amnesty, each time somebody said, I am sorry, I am very sorry, we would’ve said, Ah, he’s just putting that on.

As it happened, despite the fact that it was not a requirement, when people were applying for amnesty, almost always they would turn to the victims or the survivors, or the family, if the person had been killed, and they would turn to them and say, Please, we know it’s very difficult, but please, forgive. And as I say, almost always, the victims would.

Tippett: In conversations I’ve had across the years with people who were around the Truth and Reconciliation Commission or involved in it, they also talk, though, about it was truth and reconciliation, and that those are different things, and that they also learned about the distance that has to be walked, between truth, and even forgiveness, and reconciliation, which seems to be so much — to need so much time. I wonder where your thinking and your experience is now on that. Has reconciliation come to South Africa? Or what is the process that’s playing itself out now?

Tutu: I’ve always given people the example, when they ask that question — Have you achieved reconciliation? — and I say, just look at Germany. West Germany and East Germany were separated maybe, let us say, 50 years. They speak the same language. They are the same ethnic group. Go to Germany even today and ask, has reunification helped? Are you reconciled? And it’s amazing to discover that they are still alienated from one another.

Now, that’s people speaking the same language. That’s people who have been separated for about 50 years. We had this separation, political separation, for three centuries …

Tippett: And it was a much more violent and brutal separation.

Tutu: … about 300 years. We now have 11 official languages. So you can see how many ethnic groups we have. To have expected that we would achieve reconciliation is the height of naïveté, I think.

The act that set up the Truth and Reconciliation Commission has as its title “The Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation.” It’s the “promotion.” It doesn’t say the

“achievement.”

Tippett: Right. It’s the process you’re setting in motion.

Tutu: That reconciliation is a process. It’s not something that is just an event. And we constantly were saying, it is a national project, where every South African has to make their contribution. And it is a process. Not even the best commission could have achieved it for us.

[music: “Thina Sizwe” by SABC Choir]

Tippett: There is a lot of violence in South African society right now, and that violence is connected, as you say, to these 300 years that couldn’t possibly be resolved by the Commission. How do you think about what’s happening now, and that as part of this project?

Tutu: I think that we have very gravely underestimated the damage that apartheid inflicted on all of us, the damage to our psyches, the damage that has made — I mean, it shocked me. I went to Nigeria when I was working for the World Council of Churches, and I was due to fly to Jos. And so I go to Lagos airport, and I get onto the plane, and the two pilots in the cockpit are both Black. And I just grew inches. You know? It was fantastic, because we had been told that Blacks can’t do this. And we have a smooth takeoff, and then we hit the mother and father of turbulence. I mean, it was quite awful; scary. Do you know, I can’t believe it, but the first thought that came to my mind was, Hey, there’s no White men in that cockpit. Are those Blacks going to be able to make it?

Well, of course, they obviously made it. Here I am. But the thing is, I had not known that I was damaged to the extent of thinking that somehow, actually, what those White people who had kept drumming into us in South Africa about our being inferior, about our being incapable, it had lodged somewhere in me. And so whilst we have had this process — which was an important process, we wouldn’t be where we are without it — we certainly are needing a great deal more, the most important being a recognition that we are damaged. We are wounded people.

We accepted it, to some extent; I mean, the commission realized that we were not a cut above fellow South Africans. We were but wounded healers. And we used to make sure, when we had these public hearings, that the furniture demonstrated it. We didn’t sit on a platform higher than, but we deliberately said, We sit on a level with the victims.

[music: “Ncedo” by Dorothy Masuka]

Tippett: Here’s Desmond Tutu speaking at the National Press Club in 1999, the year after the TRC concluded its formal convening.

Tutu: We had this remarkable process of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, when people who had suffered grievously, whom you could have said had a divine right to being angry and filled with a lust for revenge, came, and they told their stories. And so frequently, you wanted to take off your shoes, because, you said, “I’m standing on holy ground.”

[music: “Ncedo” by Dorothy Masuka]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[music: “Ncedo” by Dorothy Masuka]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today we’re remembering Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who died in the last days of 2021. When I sat down with him in 2010, we explored his long view of the history he helped shape and how his understanding of God and humanity unfolded through it. Desmond Tutu saw reconciliation as an ongoing national project, not something that was perfected and completed with the end of the Truth and Reconciliation process in 1998.

I think a lot these days about colonialism, which, as you say, it’s not just 50 years of apartheid, it’s 300 years. And it’s so ironic, because also, Western support for South Africa had to do with South Africa as a bulwark against communism, and we — I mean, here I’m saying we in the West — have forgotten this.

Tutu: Well, you know, when things get rough — I mean, we also forget that we’ve been free for only about 16, 20 — 16 years; 1994. And how long have you been free? Three hundred years, something. And I’ve sometimes said, well, you know, the history of Europe, of the West, gives me a great deal of hope. [laughs]

I mean, when you think that you’ve had two world wars, you’ve produced the Holocaust, you’ve produced ethnic cleansing, you’ve had dictatorships — I mean, in Spain, in Portugal, in Greece — so, I say, look now, how you have advanced. So there’s hope for us. [laughs]

Tippett: I like that.

I wonder, also, is it right you were 63 years old when you voted for the first time? What was that like?

Tutu: How do you describe falling in love? [laughs] I mean, people asked then, when we voted for the first time. It was an incredible experience. For you, going to the ballot box is really a political act. For us, it was a religious act. It was a spiritual experience, because you walked into the polling booth one person, with all of the history of oppression and injustice, and all the baggage that we were carrying. And you walk, and you make your mark, and you put the ballot into the box, and you emerge on the other side. And you are a different person: you are transfigured. Now you actually count in your own country.

Hey, I mean, it really was a cloud nine experience. We were transformed from ciphers into persons.

Tippett: You know, one thing that I feel also runs throughout your writing is how freedom in terms of politics, I mean this freedom to vote, is absolutely something you demanded and needed to demand, and yet you also knew people across the years who were free while they were imprisoned. And there’s also the specter now of people who are politically free but not free in, I don’t know, maybe the deepest Christian sense, for example. So I wonder if you’d reflect a little bit on what you’ve learned about the limits of politics.

Tutu: Well, you know, I mean, you’ve got prepositions: the preposition “from” — you are “free from,” and then, you are “free for.” We have gone to being “free from,” which turns out to be one of the slightly easier things to get to do, although it took so long. Being “free for,” I tell you, is tough. You know —

Tippett: So what is the freedom for, what, that you now wish for, for your people?

Tutu: I think many of us were involved. I often say, you know what? We didn’t struggle in order just to change the complexion of those who sit in the Union Buildings. The Union Buildings are something like your capitol and so on. It wasn’t to change the complexion. It was to change the quality of our community, society. We wanted to see a society that was a compassionate society, a caring society, a society where you might not necessarily be madly rich, but you knew that you counted.

We’ve got a number of the things, sort of material, political things. Not all of them; I mean, we have levels of poverty at home that are unacceptable; there’s the crime; there’s disease. We still do not, I think, have the kind of place where you say, I really am proud to be here; I know that even when I don’t have a big bank balance, I count, I matter.

What we have found is that original sin actually doesn’t know very much about racial discrimination. Original sin infects all of us. I mean, when you see how so soon people have become corrupt, it leaves you feeling sad.

[music: “Congo” by Miriam Makeba]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, we are revisiting my conversation with Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who died in the final days of 2021. After he retired as the Archbishop of Cape Town, he became a somewhat controversial figure in the global religious landscape, with his insistence that sexual orientation, like racial equality, is a basic human right.

[music: “Congo” by Miriam Makeba]

You know, words that you use, like “hope” — and hope as opposed to optimism, I’m with you there, that it’s different — and “goodness,” which is in the title of this book you’ve written with your daughter, Mpho — let’s say, as a journalist, it’s very hard to make those words as interesting, and to make those words and the people you’re pointing at, and the situations that are attached to those words, to make them seem as telling, as substantial, as violence, injustice, evil, war. Have you thought about that?

Tutu: Well, yeah, but I have to say, you know, if you are devoid of hope, then roll over and disappear quietly. Hope says, Man, hey, things can, things will be better, because God has intended for it to be so. You know? At no point will evil and injustice and oppression and all of the negative things have the last word. And, yes, there’s no question about the reality of evil, of injustice, of suffering. But, you know, at the center of this existence is a heart beating with love; that you, and I, and all of us are incredible. I mean, we really are remarkable things — that we are, as a matter of fact, made for goodness.

And it’s not just a smart-aleck thing to say. It’s just — it’s a fact, because all of us, even when we have degenerated, know that the wrong isn’t what we should be, isn’t what we should be doing — that we’re fantastic. I mean, we really are amazing.

Tippett: You know, you told a story at a conference in 1990 about a man during the apartheid era, and of his village that had been demolished. People were being uprooted, and he prayed, Thank you, God, for loving us. And you wrote, “I’ve never understood that prayer.” But I think people might look at you and the life you’ve lived, and also, you know, the bad things that continue to happen in South Africa and the rest of the world, and say, This guy says this is a moral universe? And there’s this line that you’ve just echoed — you’ve written this so many times — “God is in charge.” And they might also say, How can he say that? I mean, tell me, you’ve been saying “God is in charge” for a long time; for decades. And so what do you mean when you say that, and has what that means to you, has that changed? Has that evolved?

Tutu: [laughs] Well, I mean, you must add that I’ve sometimes said to God, It would be nice for you to make it slightly more obvious that you’re in charge. [laughs]

But don’t you believe this? I mean, when you encounter somebody good — just take the Dalai Lama.

Tippett: Right, your friend, the Dalai Lama.

Tutu: Yes. Just take the Dalai Lama. Now, this is someone who’s been in exile for over 50 years. How should he really be? I mean, he’s missing his beloved Tibet. He’s missing his people. He’s been made to live a life that he wouldn’t really want to live. By rights, I mean, when you meet him you expect somebody who is bitter; who, if you mention the Chinese, will wish the worst possible to happen to them.

But you meet him, he’s actually quite mischievous. He’s fun. He’s laughing. And people flock to hear him. And, you know, he doesn’t even speak English properly, you know. [laughs]

Tippett: And they still flock to hear him.

Tutu: No, no, I mean, I must tell you, I’m not — no, no, actually, I’m not jealous. But, I mean, look at the number — I mean, he can fill Central Park.

Tippett: So this is another question I wanted to ask you. I’ve talked about how has your sense of reconciliation developed. How has your sense of Christian truth evolved through experiences you’ve had, coming out of apartheid with the Nobel Peace Prize — for example, your friendship with the Dalai Lama, this great Tibetan Buddhist leader?

Tutu: Do you really think that God would say, “Dalai Lama, you really are a great guy, man. What a shame you’re not a Christian”? [laughs] I somehow don’t think so. I think God is just thrilled, because no faith, not even the Christian faith, can ever encompass God or even be able to communicate who God is. Only God can do that.

[music: “Ingoma Ka Ntsikana” by Mara Louw & the African Methodist Choir]

Tippett: This is a big subject to introduce right here at the end, but does it strike you — the irony that, in many ways, the British were very complicit in this 300 years that your country is now recovering from, and you are an archbishop in the Anglican Church?

Tutu: Isn’t that an example of God’s sense of humor?

Tippett: It’s pretty amazing. It’s amazing. And that church now, globally, is very divided over issues of sexuality, and you have applied your experience in apartheid in a pretty provocative way, in terms of where you come out on that.

Tutu: Well, you know, there are, yes, there are many in Africa, in the Anglican Church there, who hold views that I wouldn’t hold myself, over this. And I’ve often said, what a shame — well, really, what a disgrace that the church of God, in the face of so much suffering in the world, in the face of conflict, of corruption, of all of the awful things — what is our obsession? Our obsession is not ministering to a world that is aching. Our obsession is about sexual orientation.

I’m sure that the Lord of this church, looking down at us, must weep and say, “Just what did I do wrong now?” because our church has been, in many ways, wonderful, you know, in its being comprehensive. It’s something that we’ve boasted about, the comprehensiveness of our church where, we say, we hold points of view that are often diametrically opposed, but we remain in the same family.

Tippett: So your work continues, your work of reconciliation.

Tutu: No. I’m retired.

Tippett: [laughs] OK.

[music: “Black is Beautiful” by Ladysmith Black Mambazo]

Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu died on December 26, 2021, in Cape Town. He was 90 years old. His books included No Future Without Forgiveness, Made for Goodness, and The Book of Joy, which he wrote together with his great friend the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet. You can find my full, unedited conversation with him in the On Being podcast feed or at onbeing.org. And there’s also a video of our time together while he was on spiritual retreat. That’s at the new On Being Project channel on YouTube.

[music: “Lizobuya” by Mbongeni Ngema]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt, Gautam Srikishan, Lillie Benowitz, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Matt Martinez, and Amy Chatelaine.

Special thanks this week to the Fetzer Institute, where Desmond Tutu was on retreat at the time of our interview.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear, singing at the end of our show, is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org;

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org;

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives;

The Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education;

And the Ford Foundation, working to strengthen democratic values, reduce poverty and injustice, promote international cooperation, and advance human achievement worldwide.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.