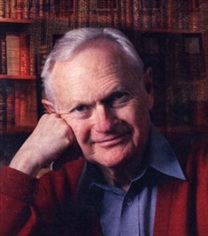

Sherwin Nuland

The Biology of the Spirit

Dr. Sherwin Nuland died this week at the age of 83. He became well-known for his first book, How We Die, which won the National Book Award. For him, pondering death was a way of wondering at life — and the infinite variety of processes that maintain human life moment to moment. He reflects on the meaning of life by way of scrupulous and elegant detail about human physiology.

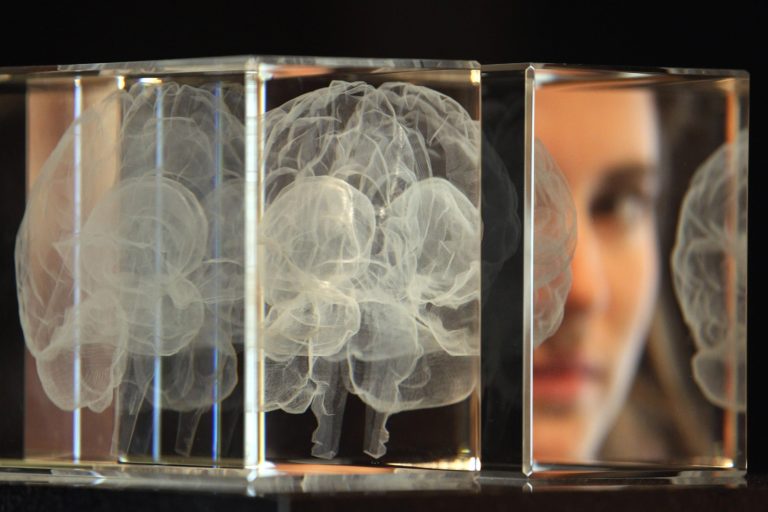

Image by Dan Kitwood/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Sherwin Nuland was a clinical professor of surgery at Yale University, where he also taught bioethics and medical history. His books include How We Die, Lost in America, Maimonides, and How We Live: The Wisdom of the Body.

Transcript

March 6, 2014

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: You tell so many wonderful stories in all your writing. You chose to write about your grandmother, your Bubbeh, in How We Die. You wrote about her death, and, you know, so many of the stories you tell are about moments in surgery or in hospitals and individual lives in the balance, and they’re all so unique.

SHERWIN NULAND: Do you know what I learned from writing that book, if I learned nothing else? The more personal you are willing to be and the more intimate you are willing to be about the details of your own life, the more universal you are.

When you recognize that pain and response to pain is a universal thing, it helps explain so many things about others, just as it explains so much about yourself. It teaches you forbearance. It teaches you a moderation in your responses to other people’s behavior. It teaches you a sort of understanding. It essentially tells you what everybody needs. You know what everybody needs? You want to put it in a single word? Everybody needs to be understood. And out of that comes every form of love.

[Music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

MS. TIPPETT: Dr. Sherwin Nuland died this week at the age of 83. He became well-known through his first book, How We Die, which won the National Book Award in 1994. But pondering death was for him a way of wondering at life. He reflected on the meaning of life by way of scrupulous and elegant detail about human physiology.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

Sherwin Nuland was a clinical professor of surgery at Yale University and a practicing surgeon for 30 years. After the success of his book about death, Dr. Nuland turned his attention to the infinite variety of processes that maintain human life moment to moment. I spoke with him after a 2005 presentation at the Chautauqua Institution in New York. Here he is before that audience, describing just one of the body’s minute processes, the DNA repair enzyme.

[Music: “Physical Liaison” by Clint Mansell ]

DR. NULAND: (excerpt from presentation) Here we are with our 75 trillion cells. It’s been estimated there are about 4 million cell divisions every single second. You’re working so hard while you’re sitting here. And when cells divide, of course it’s impossible for the DNA to replicate perfectly each time, so little mistakes are made. You know, this is how mutations arise. The DNA repair enzyme is a molecule. It’s a complex molecule. It travels like a little motorboat up and down the DNA molecule. It finds errors, snips them out, corrects them, and puts the right thing back in there. This is the ultimate wisdom of the body.

MS. TIPPETT: The Wisdom of the Body is the title Sherwin Nuland gave to a book he published in 1997. He chose as its epigraph a quote of St. Augustine:

“Men go forth to wonder at the heights of mountains,

the huge waves of the sea,

the broad flow of the rivers,

the vast compass of the ocean,

the courses of the stars,

and they pass by themselves without wondering.”

Sherwin Nuland believed that human beings, alone among living creatures, became aware over time of the cost of decay in the world around them and of their own finitude. “In response,” he wrote, “our brains developed a capacity for spirit, for seeking lives of integrity and equanimity and moral order.”

MS. TIPPETT: I would like to ask you, and this is a way that I often begin my interviews, whatever the subject is, to say a little bit about the religious background of your early life that you grew up with?

DR. NULAND: Are we on?

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. We’re on, We’re on.

DR. NULAND: Well, I was born into an Orthodox Jewish family that were immigrants. Everybody had come from Eastern Europe specifically my mothers side from the Russian Pale and my fathers side from what is now called Moldova. Which at that time was best Sarabia, it’s on the Romanian border. And they came here in stewards like everybody else and had no money like everybody else. The difference between them and everybody else seems that everybody else went to night school to learn to read and write english and for some odd reason no one in my family ever did. So we remained in many ways unassimilated so the religious background remained Orthodox Jewish but it was sort of a, how can I put it, well this is what we are so you know we go to synagogue on certain occasions and we have Passover seder and do all these things but no one is really educated on all of this, we only know this what we do.

But as far as a scholarly approach or learned approach there wasn’t any such thing. So the kids are brought up this way and everybody goes to hebrew school and everybody has a Bar Mitzvah and this is again bingo. It is no question about what the family tradition is and what the family will always be. I actually took all of this very, very seriously. I took it more seriously than anyone else in the family. And thoughts of God were very important to me and God’s will and my behavior in respect to that became and remained very important to me. And as I got older that didn’t lessen that whole didn’t lessen if anything it got stronger and that is the story of my early religious background. But that’s as much as you’ve asked.

[Laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: Well I don’t, do you want to tell me more?

DR. NULAND: Only if you need for me to tell you more. I’m happy to tell you more but I’m just answering the question I’ve been asked.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah lets continue to talk about that as it’s relevant to some of the things you’ve been thinking about in more recent years.

DR. NULAND: Sure.

MS. TIPPETT: You spent 30 years as a surgeon and I don’t know, I read somewhere that over three decades you cared for more than 10,000 patients.

DR. NULAND: Yeah, sure.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah and you wrote this book called The Wisdom of the Body. And you wrote “not alone the structure of us but also infinite variety of processes by which we maintain that singular constancy and unity of moment to moment life has inspired me to write this book. I want everyone to know what i have come to know.” I would love to hear about where that longing grew in you to share what you know.

DR. NULAND: Well the best way to learn about normal structures and normal function, I think, is to study disordered structures and disordered functions. So when you’ve spent 30 years in clinical practice but it was six years of training before that and four years of medical school before that.

When one has spent that amount of time studying abnormalities, one develops an enormously healthy respect for normal. One develops an enormously healthy respect for the equilibrium that is maintained in order for us to continue in healthy life, especially when you’re in surgery and you look inside an abdomen and realize how many things could go haywire and they don’t. Or you look at the structures that you’re dealing with and recognize that everything is just humming along beautifully, nobody is running it. It’s just going by itself and the orders are coming from somewhere. This little bit of pathology that you’re taking care of is in the corner somewhere. Now, we know it affects the whole body, but when you look at it, you’re most impressed with the normal structures.

MS. TIPPETT: What brought you though, you were 61 when you began to write. Right?

DR. NULAND: No No No I was younger than that. I wrote a book that was published in 1988. So I was probably about 56 when I began to writing.

MS. TIPPETT: Alright, what brought you to want to write about all of this for other people who are not physicians.

DR. NULAND: Well it wasn’t my plan. What actually happened and you are about to get much more than you want.

MS. TIPPETT: No that’s ok.

DR. NULAND: What actually happened was that the phone rang one day and a man on the other end said that he was a literary agent and there was a book that he thought needed to be written and he had been looking around for someone to write it. And several editors in New York mentioned my name because I had written some stuff. And the book he said was to be called How We Die.

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, so he presented that idea?

DR. NULAND: He presented the idea, presented the title, he said do realize you know no one really knows what happens when we die? And I said that’s silly, it must be in medical textbooks. Well, to shorten this story as much as I can, no, it wasn’t in any textbook. And here are families and here are dying people living through this “terra incognita” and I could even spell terra T-E-R-R-O-R- because it is indeed a terrifying terra. Not knowing what to expect the next day and thinking everything is out of control as the body deteriorates, as the mind deteriorates, and wouldn’t it be wonderful if people really understood what to expect and knew that as bad as things were this is the way you die, of cancer, or of heart disease, or of stroke, this is — if we can use that word in that sense — it’s normal. And I though that would be very reassuring to people because my experience in medicine had been that if I told a surgical patient just what to expect, he could tolerate pain much better, he could tolerate drainage and discomforts and diarrhea because he knew that was supposed to happen and that was okay. So why shouldn’t that be true of the months and weeks before death. And that seemed like a noble cause when he suggested that I write such a book. So I agreed to do it and both he and I were surprised at the book that was written.

MS. TIPPETT: That was How We Die.

DR. NULAND: That was written, it was How We Die. He and I didn’t speak again for another year while I wrote the book and I had no plan except what I’ve just described to you and I just chose the diseases that are most prevalent that cause death in our society, in western society, and wrote about them. And to my amazement, when it was all over, there was a beginning, there was a middle and there was an end and there were expressed in the text philosophies of death and dying and treatment of the dying that I had obviously been following all my career and never consciously thought to think about it but there they were in print. So i developed a healthy regard for what goes on in the unconscious mind and everything I’ve written since then has been done in exactly the same way.

MS. TIPPETT: Oh so really, it’s interesting you wrote first about death and later, this later book The Wisdom of The Body, more about how we live, about how you say the organizational principles. But you are saying really it was the act of writing that first book, as much as what you know that led to that next step.

Remember I was saying a moment ago about that the thing that makes you want to seek out the normal is constant contact with the abnormal you really want to know what has gone wrong and why it has gone wrong and what state it goes wrong from because you begin to wonder why don’t more things go wrong. Especially when you’re in surgery and you look inside an abdomen and realize how many things could go haywire and they don’t. Or you look at the structures that you’re dealing with and recognize that everything is just humming along beautifully, nobody is running it. It’s just going by itself and the orders are coming from somewhere. This little bit of pathology that you’re taking care of is in the corner somewhere. Now, we know it affects the whole body, but when you look at it, you’re most impressed with the normal structures. And sitting right in the middle of this really ugly thing, whether it’s a cancer, or a disease gallbladder, whatever it may be and yet everything else is going along fine. All you have to do is get that bad thing out of there and the body goes back to being perfectly healthy.

[Music: “Morning Sun” by Miaou]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today my interview with the late author and surgeon Sherwin Nuland.

MS. TIPPETT: You also had a serious experience of depression, which you wrote about in a more recent book, Lost in America, that was that book, and I’d also be curious about how that experience formed your interest, your fascination with your physical self, with the body.

DR. NULAND: Well, that’s the next step in the story of my religious experience. Because when I became depressed, and became a victim of obsessional thoughts, as people do when they are depressed, you keep mulling over things and ruminating over things.

MS. TIPPETT: I’ve been there by the way, so I know what you are talking about.

DR. NULAND: Oh well I’m sorry to hear you are a member of the club. It’s a much bigger club than most of us ever dreamed of,extraordinarily bigger. When I became depressed I came very quickly to admit something to myself that I had really been aware of on some level but refused to come out and say directly, which was that my religious beliefs, what I thought were my religious beliefs, were nothing more than obsessional thinking, that it really had to do with fear of, whether you want to call it hellfire or punishment of some kind.

MS. TIPPETT: And these would be the beliefs of this Orthodox Jewish upbringing?

DR. NULAND: I don’t know. How does one know? Certainly I, since that time, have met many, many, many Jews, just as I’ve met many Catholics and Protestants who have deep faith, who really believe, and obsessional thinking has nothing to do with it, and fear of punishment has nothing to do with it. This is true faith. But my problem was me and not what Judaism represents.

And it was clear to me that the behaviors that I was exhibiting, that I thought were in keeping with Jewish religious precepts, had to do with superstitious fears of punishment. And they were indeed a symptom of a long-term obsessional neurosis. And if I was going to get out of this depression, I was going to have to give that all up. And I did. Interestingly, you know, people think well, you know, we’ll take pills, we’ll take electroshock therapy, we’ll get psychotherapy, and we will gradually get better and they forget that you reach a point in an emotional illness, on the upswing, when you’re starting to get better, when you have to make a decision because you’re now strong enough to make it. The decision is, ‘Am I going to hang on to these symptoms?’ Because the symptoms become very meaningful to you, you depend on them, you’re comfortable with them. They represent things to you.

MS. TIPPETT: What are you thinking of when you think of a symptom that you had for example?

DR. NULAND: Well, some of my obsessional thoughts. And they were obsessional thoughts about all manner of things. And I realized that a therapist helps you with this kind of stuff but you, doesn’t have to help very much because it’s pretty clear if you’re thinking about it. They represented a sort of comfortable familiar thing that I could come back to. It’s almost as if they represented family. And it’s hard to give those things up. It’s very difficult. There’s an old suit and it looks terrible on you, but you like it, you know it’s really good, and the elbows are patched and you feel like sitting by a fire and smoking a pipe in that suit but you know that if you do that you’re never going to get in the world and live. And it’s very much–I like that analogy as a matter of fact–it’s very much like that with neurotic symptoms. If you’re going to get in the world and really accomplish something and really understand the way that the world functions, you’ve got to get rid of all that stuff. And I just did it. I did it by an act of will.

MS. TIPPETT: But, so then the question is, I mean, since that time, is there a connection between what you gave up in terms of these obsessional thoughts, the religious ideas that weren’t good for you, and then what you began to think about in their place? Because you didn’t really stop thinking about what it means to be human or the fact that there’s a human spirit, which are often connected with religious beliefs.

DR. NULAND: Well, that’s right. That’s right. It’s the human spirit that got me through. It was the sense that there is a richness in this world that’s enormous fun if you can find it, and it’s the kind of fun that you can have while actually making the world a better place for other people, too. There’s an integrity to it in the sense of a oneness, of a unity, that if you are discovering the essence of what it means to be human, you are freeing yourself from all these enmeshings and thinking about yourself. So you’re really thinking about humanity and the human spirit and, accordingly, other people. And the sense of accomplishment when you accomplish something from that intellectual and emotional background is enormous because of the freedom.

I was shackled by neurotic thoughts, by essentially being so twisted in the meaning of what I was doing, the meaning from myself, the spiritual meaning from some supernatural being that I didn’t really understand. Once that was gone, what a wave of freedom, what a liberating thing it was. It was as though I’d been bottled up and someone took the cork off the bottle, and this thing — it didn’t leap out; it sort of, ooooooh, came out. And luckily for me, it’s continued to come out, because when one gets tempted to take up the obsessions or neurotic symptoms again, one begins to think of not just the cost of doing that but what you would lose, the pleasure that you would lose, the rewards you would lose, the sense of self you would lose, the feeling of being a part of an open community that you would lose. I know this is a lot of abstraction.

MS. TIPPETT: No. I don’t think it’s abstraction. And I think a lot of people will know what you’re talking about and will recognize themselves there. I mean, but again, you know, what I think is fascinating is that you thought about the human spirit in a whole new way, and your spirit, it sounds like. And you did so also by connecting that with the work of your life, with your work with the human body. I mean, here is some language from your book: “The human spirit is the result of the adaptive biological mechanisms that protect our species, sustain us and serve to perpetuate the existence of humanity.” You know, that could sound like a kind of antiseptic and reductionist statement, but in fact…

DR. NULAND: Sound like a meaningless statement.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, no, but you make it and you surround it with ideas with a sense of great wonder.

DR. NULAND: Well, you just got the word. I’ve been sitting here on the edge of my seat, hoping, ‘When am I going to get to say this word, wonder?’ Wonder is something I share with people of deep faith. They wonder at the universe that God has created, and I wonder at the universe that nature has created. But this is a sense of awe that motivates the faithful, motivates me. And when I say motivates, it provides an energy for seeking. Just as the faithful will always say, ‘We are seeking,’ I am seeking.

We’re seeking different things. I’m seeking an understanding of this integrity of everything, of this unity of everything, of the equilibrium of not just the homeostasis, as the physiologists say, the staying the sameness, but of the closeness that we are constantly coming to chaos. I have had chaos. I’ve had chaos to the point where I thought my mind was lost, which gives me a deeper appreciation of equanimity, not just to continued existence but to continued learning, continued productivity, this kind of thing.

MS. TIPPETT: Let’s backup a little bit and expand on that for somebody who is hearing these ideas for the first time. I mean you really do suggest that the human spirit is something of an evolutionary accomplishment.

DR. NULAND: I think there is an evolutionary accomplishment of the human cortex, the cortex of the brain, and the way it relates to the lower centers of the brain and the way it relates to the entire body, the way it accepts and synthesizes information, uses information from the environment, from the deepest recesses of the body, the way it recognizes dangers to its continued integrity. And I think that this is precisely what the human spirit is doing. The human spirit is maintaining an equilibrium, and it largely is related to its normal physical and chemical functioning.

MS. TIPPETT: So there’s a biological underpinning for intelligence that evolved over a great large span of time in human beings, but then that we developed something else which is consciousness. Is consciousness the same as spirit?

DR. NULAND: I don’t think so. Consciousness is only a kind of an awareness of our surroundings, an awareness of our emotions, an awareness of our responses. The human spirit is something much greater. The human spirit is an enrichment. It’s the way we use our consciousness to, I keep using this word, to synthesize something better than our mere consciousness, to make ourselves emotionally richer than we in fact are.

MS. TIPPETT: So that almost to transcend what was given.

DR. NULAND: To transcend. And this is what I mean when I say that we are greater than the sum of our parts, that because of the kinds of trillions of cerebral connections we have, and the way our species for the past 40,000 years since modern Homo sapiens appeared on Earth, the way we have adapted to stimuli from the outside, we have relentlessly pursued this upward course, I believe, toward creating the richness of the human spirit.

There is a word that the neuroscientists use when talking about why a certain series of circuits or group of circuits in the brain is activated. The word is value. There are pathways in the brain that have survival value. So when a stimulus comes in and the brain has 50,000 different ways of responding to it, some of those are useful for survival and some of those will either prevent survival or mar survival, and the human brain, in classical evolutionary pattern, will pick the one that is healthiest, that gives greatest pleasure. What gives greater pleasure than a spiritual sense? So I think of this as natural selection in a form, in an emotional form, and I think it is almost like choice because when you’re talking about selection in the brain, there are processes of choice. The brain has a way of evaluating what is best for the organism. And what is best for the organism is not just survival and reproduction but beauty, but an esthetic sense.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. So that we as human beings have chosen to value beauty.

DR. NULAND: You bet. We’ve chosen. Now, it’s an unconscious process, but what we know about unconscious processes are that for every conscious process there are 8 million zillion trillion unconscious ones, and they are in fact what will eventually determine what’s conscious and what we can understand. So again, to reiterate, this is a process of natural selection. A stimulus comes in. There are many, many ways of responding to it. Some of those ways are counterproductive, some are kind of ordinary, and some really give satisfaction and enhance the richness of our lives. And without knowing it, our circuits are choosing those, and this is what I mean by the human spirit.

MS. TIPPETT: And I want to just say, you know, say someone who’s listening who hasn’t read your work, what we’re not talking about is the loving detail with which you describe these trillions of circuits and what is happening, how amazing those biological mechanisms are, and how amazing you find it to be.

DR. NULAND: It’s wonderfully exciting. Here are these 75 trillion cells, and every cell has hundreds of thousands of protein molecules in it and they are constantly interacting with one another in what would appear to be chaos. And in fact, if you were to be able to lower yourself into a cell, you’d be terrified because it would seem so chaotic. If it had sound, you couldn’t live with it, it would be so noisy. And yet what is actually occurring is that these reactions are all counteracting threats to the survival of that cell. And I think that there is within the human organism, only the human organism because of our cortex and our ability to process information, I think that there is an awareness of the closeness of chaos.

And I think there’s a lot of evidence for that, including cultural evidence. And I talk often about the polarity of our thinking. We talk about good and evil, and one of my favorite examples of this is something I got from my Orthodox Jewish background, which is the principle of the good inclination living in balance with the evil inclination, and one must make that choice at all times. Now, the Greeks, who expressed it as chaos versus cosmos, already, without knowing anything about cells or anything about how the body really worked, they had a sense that there was an order up there in the universe, but we live in chaos. And we can use the example of the cosmos to seek the reassurance of that stability. And you know and I know you listen to the popular music that people in their teens and 20s and 30s are listening to, and if you listen carefully you’re always going to hear the heartbeat in the background.

MS. TIPPETT: What you’re saying is that we are always seeking rhythm.

DR. NULAND: Harmony, order, integrity in the sense of oneness. And this is again, I think, why monotheism. It’s just everybody says, ‘Oh, this is wonderful. The Jews discovered monotheism, the Christians embrace it, the Muslims embrace it,’ as if this has to be the right thing. Why does it have to be the right thing? Why is this better than a bunch of polyglot gods or polymorphic gods? It’s because we need unity, predictability. We need a moral sense. We need a moral sense to prevent the chaos that somehow we recognize we are living close to.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, I’m also thinking of the beginning of Genesis, of the beginning of the Hebrew Bible, where the original creative act is creating order.

DR. NULAND: That’s right. They were responding to precisely that same deep awareness that hadn’t even reached the level of the unconscious mind yet that I’m talking about.

MS. TIPPETT: The spirit, for all of its wonder and the good that we associate with it, also has base qualities and has a dark side. How do you think about that in this scheme?

DR. NULAND: Well, I think it has to do with the nearness of chaos, which is always a temptation. It’s like the butterfly and the flame. We are tempting ourselves with evil, we are tempting ourselves with that which is destructive, and we, to some extent, succumb to it. If you talk to psychoanalysts about severe neurotic disease, they often talk about the personality that skates to the edge and then rescues itself from the edge. We are so tempted to go to here with ourselves, as it were, that’s a theological expression, that we actually do come near it, even recognizing the other pole. And this is what the Greeks meant when they were talking about Eros versus Thanatos, the love and life sense against the death sense. I don’t think it’s in very many of us to deliberately choose destruction, but we play with it and it licks us and burns us and can ruin lives.

[Music: “Luna Park” by Signal Hill]

MS. TIPPETT: You can listen again and share this conversation with Sherwin Nuland through our website, onbeing.org.

Coming up…Sherwin Nuland on biology and the human spirit, including the human capacity for love, moral order, and faith.

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[Music: “Luna Park” by Signal Hill ]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today, “The Biology of the Spirit,” — my 2005 conversation with Dr. Sherwin Nuland, who died this week at the age of 83. A practicing surgeon for 30 years and a clinical professor of surgery at the Yale School of Medicine, Dr. Nuland gained literary prominence with his 1994 book, How We Die. In later years. he delved deeply into his sense of wonder at the human body’s capacity to sustain life and to support our pursuits of order and meaning. He followed the emergence of brain science with great fascination, and came to believe that the human spirit arose in an evolutionary way, as an accomplishment of the human brain.

MS. TIPPETT: It does occur to me that this idea of the soul, the spirit — I don’t know if you use the word “soul.” Do you use — would you use the word “soul” and “spirit” interchangeably?

DR. NULAND: I don’t think I ever use the word “soul,” you know?

MS. TIPPETT: All right. Well, I’m thinking of…

DR. NULAND: “Soul” has implications that I’m trying to stay away from.

MS. TIPPETT: That you’re staying away from.

DR. NULAND: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: I’ve been thinking, there is in Jewish tradition the nephesh, the soul which is emergent, which, you know, which is quite different from say the Christian idea of the soul. There is a Jewish sensibility of the soul as being something that emerges in relationship. And I do think that there is some affinity between that image and the way you imagine the human spirit to be this evolving work of humankind.

DR. NULAND: Well, I think you have just told me something I’ve got to think a lot about, because it had never occurred to me. But what I’ve got to do is think of the theological implications of nephesh, because I suspect that I know far more than I think I know, just as we all know far more than we think we know. You know, we know all these words and if we were to sit down with ourselves in a quiet room or just sit with a pencil, extraordinary things would come out. And they would be correct. So I’ve got to sit in the corner, and I’ve also got to talk to some better theologians than I about the implications of nephesh, because I assume — why does this hit me so hard? Because I assume that I know things about that concept that I don’t realize I know.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, it may have been something you breathed in in that Orthodox Jewish air that you grew up in.

DR. NULAND: Well, you do — it all is related, you know, to the Greek notion of pneuma, the notion that the soul exists in the universe and with your first breath you inhale the pneuma, P-N-E-U-M-A, and that is the life-giving force. “Pneuma” is actually etymologically related to “psyche.” So you get psyche, spirit, soul all together in one, but the origin of it is this thing that you inhale. So all of these traditions end up going back, I think, to something that all Homo sapiens share. So if all Homo sapiens share it, one of two things has to be true: either God gave it to everybody, or it’s a universal within our–on some level of awareness or it’s in our DNA or something of this. I choose to think it’s biological.

MS. TIPPETT: You tell so many wonderful stories in all your writing. You chose to write about your grandmother, your Bubbeh, in How We Die. You wrote about her death, and, you know, so many of the stories you tell are about moments in surgery or in hospitals and individual lives in the balance, and they’re all so unique. It really struck me that you wrote about your grandmother and you talked about how many letters you got from people all over the country, and you quoted this pig farmer in Iowa who wrote, “Thank you so much for sharing your beloved Bubbeh with us. I now love her too, as I have known her by another name in another time in another place.”

DR. NULAND: Exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: It struck me, this paradox of how different we all are in every one of our situations in living and dying and yet how alike, yet how there are these images of humanity.

DR. NULAND: Do you know what I learned from writing that book, if I learned nothing else? The more personal you are willing to be and the more intimate you are willing to be about the details of your own life, the more universal you are.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Isn’t that interesting?

DR. NULAND: Isn’t that interesting? And when I say universal, I don’t mean universal only within our culture. You know, there’s a lot of balderdash thrown around, ‘You don’t understand people who live in Sri Lanka and their response to the tsunami because you just don’t know that culture.’ Well, there’s an element of that, but to me, cultural differences are a kind of patina over the deepest psychosexual feelings that we have, that all human beings share, that they share by virtue of the physical properties of their body and the kind of brain that they have, which bring out certain sorts of strivings, certain sorts of emotional needs that are indeed universal.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. And how do we make use of that knowledge, or do we just know it?

DR. NULAND: I think we make use of that knowledge to perpetuate love. There is a book that I wrote called Lost in America, and there is a quotation in that book. It’s the epigraph of that book, and it’s attributed to Philo. Nobody who’s a Philo expert has been able to find it for me, and I certainly can’t find it. “Be kind, for everyone you meet is carrying a great burden.” Well, that’s the philosopher’s stone.

When you recognize that pain and response to pain is a universal thing, it helps explain so many things about others, just as it explains so much about yourself. It teaches you forbearance. It teaches you a moderation in your responses to other people’s behavior. It teaches you a sort of understanding. It essentially tells you what everybody needs. You know what everybody needs? You want to put it in a single word? Everybody needs to be understood. And out of that comes every form of love. If someone truly feels that you understand them, an awful lot of neurotic behavior just disappears. Disappears on your part, disappears on their part. So if you’re talking about what motivates this world to continue existing as a community, you’ve got to talk about love. And you can’t talk about — oh, I’m going to get into hot water for this, you can’t talk about this phony concept of love that so many of the religious throw around based on God’s love. You’ve got to think about this in terms of human biology, including emotional biology.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. I mean, love is such a watered down wishy-washy word in our culture.

DR. NULAND: Well, sure. It’s misused, it’s bastardized.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. NULAND: And it becomes somebody’s slogan.

MS. TIPPETT: But, I mean, I’m thinking when you talk about — if you approach everyone, as you say — I love this epigraph, “Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a great battle.”

DR. NULAND: That’s it, fighting a great battle.

MS. TIPPETT: Is fighting a great battle.

DR. NULAND: Yes, that’s even better.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, that — but, you know, what that also engenders, the qualities you spoke about: patience, hospitality, compassion — virtues that are at the heart of all the great religious traditions, right?

DR. NULAND: Of course. There’s the universal again. And my argument is it comes out of your biology because on some level we understand all of this. We put it into religious forms. It’s almost like an excuse to deny our biology. We put it into pithy, sententious aphorisms, but it’s really coming out of our deepest physiological nature.

MS. TIPPETT: I also, though, as I read you, you’re very clear that some people could read the way you describe reality and even your sense of spirit as something that has evolved and could also be religious and hold that together with a sense that there’s a God.

DR. NULAND: Of course. And these are two different belief systems. There isn’t a reason in the world that the religious have to explain their faith on a scientific basis. It makes no sense. What is needed between science and religions is not a debate but a conversation, each one saying, you know, ‘You’re here to stay and I’m here to stay, so let’s find out how our relationship can be of greatest benefit to this world.’ And in the new book on Maimonides, I pointed out that this debate between the two did not exist until the philosophers of the Enlightenment created that debate.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, let’s say who Maimonides was, a physician and a philosopher…

DR. NULAND: Yes. And a theologian.

MS. TIPPETT: …and a theologian.

DR. NULAND: Yeah. Aquinas was a philosopher and a theologian. Averroës was a physician, a philosopher and a theologian. All three of these people knew essentially all the knowledge available to anybody at that time. And they were engaged in the pursuit of bringing science and philosophy on the one hand — and specifically Greek philosophy — science and philosophy on the one hand together with faith on the other hand. That’s what they did. When people talk about Galileo, they say, ‘Oh, my God, Galileo, he was a heretic, he was’ — not at all.

MS. TIPPETT: Not true, I know. It’s just, I know. Bad history.

DR. NULAND: Galileo’s entire pursuit was to bring his theory into keeping with church doctrine.

[Music: “Still Secrets Remaining” by Hammock]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today my interview with the surgeon and author Sherwin Nuland, who died this week.

MS. TIPPETT: When I was reading you about the evolution of spirit, of sort of humanity as a creation of humankind and a creation of the brain, I was thinking of John Polkinghorne, who’s a British physicist and theologian, and he says that he believes in God, but he says God did something much more clever than create a clockwork world, God created a world that could make itself.

DR. NULAND: There it is.

MS. TIPPETT: So, I mean, it’s a way to look at…

DR. NULAND: There it is, you know.

MS. TIPPETT: …everything you’re stating and also retain a faith.

DR. NULAND: Yeah, and He gave…

MS. TIPPETT: But I’m not saying that’s — I’m not saying there’s any reason to force that either.

DR. NULAND: And you know what else He did? Let’s say categorically we’re both people of faith. He gave humankind free will, and free will becomes the essence of the whole thing. Because it’s not just free will in the conscious sense, but He would have created the free will that makes the synapses and the nerve cells and the neurotransmitters, allows them to make choices. And given the opportunity to make choices, they will always choose the more, let’s use that big word, salubrious way, and salubrious in the classical sense of healthy way, physically healthy, emotionally healthy, the thing that’s going to make it survive most likely and provide it with the most pleasure. And the moral sense provides people with more pleasure than anything. That’s been my experience, that a sense of oneself as a good person whose life isn’t sacrificed for others but is based around community and love gives one a sense of self that is the greatest pleasure that anybody can have. We say virtue is its own reward. And, you know, it’s a little homily, but there’s a lot of stuff behind that homily. Every cliché has a reason.

MS. TIPPETT: This adventure of learning about the brain, which you are steeped in, I wonder how you think this kind of knowledge will begin to reach ordinary people. You know, are there ways it will turn up in our culture at a more basic level?

DR. NULAND: What happens to science, or what has happened to science since the great discoveries began to be made around the middle of the 20th century is that increasingly the public, by reading about some of these technological events and phenomena over and over again, it starts seeping in. People are very impatient when they want to learn about this stuff. They go, ‘Well, I don’t understand this,’ and they go on to something else. But if you’re just patient and let it happen–bit by bit people began to understand DNA. In 1955, just two years after Watson and Crick did their nice thing and published that great paper, nobody could figure out what DNA was. Now everybody knows what DNA is.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, now it’s — yeah, OK.

DR. NULAND: And all kinds of notions of heredity and genetics. When people first started talking about stem cells and cloning, they were a mystery except in some sort of comedic sense. But bit by bit, people are recognizing scientific observations and discoveries. And my guess is that neuroscience, as it evolves, will slowly become something that is apprehensible to most reasonably well-educated people. Of course, it would help if we had a better way of scientifically educating 10-year-olds, but we are not in that situation in this country.

MS. TIPPETT: But you know what, the neuroscience that you’re describing is also something that I think people could use to make their lives more fulfilling. That kind of knowledge is also a form of power.

DR. NULAND: Well, I like to think that if people really understand the way their brains work, they would be as overwhelmed with wonder as some of us are, and would have a completely different sense of the human organism and its potentialities and would try to live up to its greatest potentialities.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm, Ok. That’s your last word. Thank you so much

DR. NULAND: Ok Mom, you mean it’s over. (Laughter)

MS. TIPPETT: It’s over, you may go. (Laughter)

[Music: “Finally We Are No One” by mum]

MS. TIPPETT: Dr. Sherwin Nuland died March 3, 2014 at the age of 83. He was clinical professor of surgery at Yale University, where he taught bioethics and medical history. His books include Maimonides, How We Die, and The Wisdom of the Body, which appears in paperback with the title How We Live.

[Music: “Morning Sun” by Miaou]

Here in closing are the final remarks from his talk “Brain, Mind and Spirit: The Wisdom of the Human Body,” at the Chautauqua Institution in New York, in 2005:

DR. NULAND: (excerpt from presentation) It is my spiritual self that makes me human, it enables me to reason, to sublimate my instinctual drives, to be of use to society, and to love in a way that only members of my species can love. But it also enables me to do harm, to scheme against the interests of others, and to so misinterpret the unconsciously recalled traumas of my childhood that I become depressed, anxious, or a danger to society.

The human spirit can be the high road to the fulfillment of my greatest hopes, but it can be the grim pathway to my self-destruction. Either way, it is the transcendent product of my body and its wisdom and of the most complex structure on the human planet, the three pounds of human brain. Thank you very much.

MS. TIPPETT: You can listen again or share this conversation with Sherwin Nuland, and hear his whole presentation at the Chautauqua Institution, at onbeing.org. And follow everything we do by subscribing to our weekly email newsletter. Just click the newsletter link on any page at onbeing.org

On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mikel Elcessor, Mariah Helgeson, and Joshua Rae.

[Music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

[On Being Extra]

RENATE HILLER: In a way, the entire human being is in the hands. Our destiny is written in the hand.

MS. TIPPETT: Ms. Tippett: That’s the voice of the German fiber artist Renate Hiller, in a lovely video that’s popular on the On Being blog right now called “On Handwork.”

RENATE HILLER: And in hand work, in transforming nature, we also make something truly unique, that we have made with our hands, stitch by stitch, that maybe we have chosen the yarn, that we have spun the yarn, even better, and that we have designed. And when I do that I feel whole, I feel I am experiencing my inner core because it’s a meditative process. You have to find your way, you have to listen with your whole being. And that is a schooling that we need today.”

Hear and see more at onbeing.org.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.