Trabian Shorters

A Cognitive Skill to Magnify Humanity

Trabian Shorters is a visionary who has seen and named a task that is necessary for all healing and building, for every vision and plan, whether in a family or a world, to flourish. It’s called Asset Framing — and it works with both new understandings of the brain and an age-old understanding of the real-world power of the words we use, the stories we tell, and the way we name things and people. From everyday social media, to hallowed modes of journalistic, academic, and policy analyses, we have a habit of seeing deficits — and of defining people in need in terms of their problems. This has not only doomed some of our best efforts to failure — it leaves all of us prone to cynicism and hopelessness. What’s exciting is that what Trabian Shorters proposes is not only more effective, it is simple and straightforward to grasp. It is in and of itself dignifying and renewing. The main question you might be asking at the end of this is why, at this advanced stage of our species, it took us so long to learn to asset frame.

Guest

Trabian Shorters consults widely in philanthropy, business, nonprofits, and journalism. He’s the founder and CEO of the BMe Community. He’s been a Vice President of Communities at the Knight Foundation, co-led the Ashoka-US venture team, and founded a successful early social impact tech company in 1999. He’s co-editor of the book, Reach: 40 Black Men Speak on Living, Leading and Succeeding.

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang

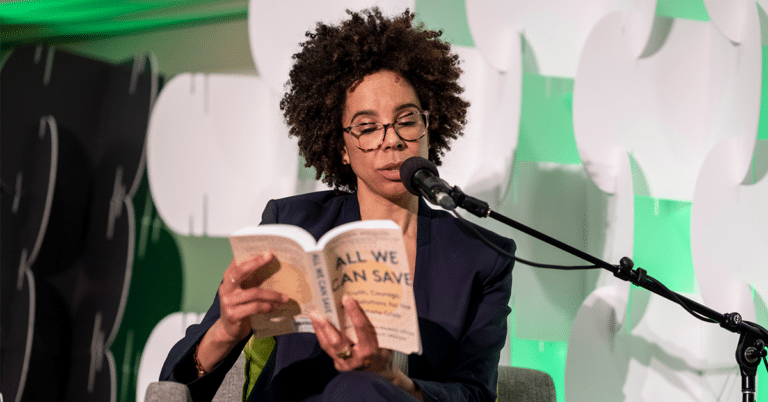

Krista Tippett, host: My guest today is Trabian Shorters, a visionary who has seen and named a task that is necessary for all healing and building, for every vision and plan, whether in a family or a world, to flourish. Yet it’s the kind of move often short-circuited in our urgency for action and solutions. It’s called “asset-framing,” and it works with both cutting-edge understandings of the brain and an age-old understanding of the real-world power of the words we use, the stories we tell, the way we name things and people. To understand asset-framing, you first have to take in its profoundly intuitive opposite, which is the way we’ve largely been living: deficit-framing. From everyday social media to hallowed modes of journalistic, academic, and policy analyses, we have a habit of seeing problems, and of defining people in need in terms of their problems.

Trabian Shorters is working with all kinds of institutions — from philanthropy to nonprofits to journalism — who are waking up to the fact that the very way we have spoken of, and therefore thought about, the people and crises we wish to serve has often instead stigmatized and sabotaged them. It has not only doomed some of our best efforts to failure — it leaves all of us prone to cynicism and hopelessness. What’s exciting is that what Trabian Shorters proposes is not only more effective, it is simple and straightforward to grasp. It is in and of itself dignifying and renewing. The main question you might be asking at the end of this is why, at this advanced stage of our species, it took us so long to learn to asset-frame.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[“Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Trabian Shorters is founder and CEO of BMe, a movement to first define black people by their aspirations and contributions. He’s been a Vice President of Communities at the Knight Foundation, co-led the Ashoka U.S. Venture team, and founded a successful early social impact tech company in 1999.

I’m always curious about the roots in a life of what become that life’s passions and callings and kind of animating questions, and also about however you would define the religious or spiritual background of your earliest life, of your childhood. So how do you think about — where does your mind go, if you think about these roots of what you care about now?

Trabian Shorters: Oh yeah, it all starts with my grandparents. So I was born and raised in Pontiac, Michigan. My mom was still a teen when I was born, and so I was raised, for the early, formative years of my life, in my grandparents’ household. And my grandmother and my grandfather are both from the South, and so they are literally the sort of almost stereotypical deep southern Negro Christians. They were — my grandfather was raised — and my grandmother, actually, but I learned it more from my grandfather — they were both raised in the love doctrine, in the idea that in order to practice Christianity, you must love people the way that God loves people. And so I got that early and often because, as far as I could tell, Grandma and Grandpa knew God personally — you know what I mean? [laughs] And so yeah, it really did infuse the household when I was growing up.

Tippett: So they started this — the Kingdom of God Outreach Ministries, is that right? Or your grandfather started that? I’ve just looked at the website; I mean, I know that there are other leaders now, but you just feel, even just from being on the website, that that’s a really special place.

Shorters: Let me elaborate on that a little bit, if it’s OK. So my grandfather was just a very straightforward, down-to-earth kind of person, and so when he retired from General Motors — and a very loving person. So when he retired from General Motors, he wanted to create a community center for kids — afterschool safe place to play, and all that. And it was his bishop who told him to “stop messing around; go ahead and start your ministry,” right? And so Grandpa started the church, but he also bought the lot next door and created the community center. So the church and the community center were started at the exact same time, because what he really wanted to do was be of service to the community. And he always — his orientation to, I guess to spirituality, but that’s not how they talked about it — his orientation to life was always about giving people what they need and, literally, loving them — like, loving them in action.

Tippett: You could also say they were asset-framing, in the way you see things now, right?

Shorters: Well, I mean, well, honestly, yeah.

Tippett: Their focus, their North Star, was love.

Shorters: Well, actually, if we want to connect those dots, here’s the fact of the matter. Asset-framing is a direct expression of the love doctrine, right? It is defining people by their aspirations and contributions, before you get to their challenges. So whatever is going on in someone’s life, you don’t ignore it, but you don’t define them by the worst moment or the worst experience or the worst potential; none of that. You have to look past their faults, to see who they really are. And even the word “aspiration,” we are very intentional about that, because it has the word “spirit” baked into it.

So what we want to do — yes. So what we want to do is acknowledge the true person, the true spirit living in someone — the thing that motivates them; what gets them moving. It is not that they are poor. They don’t wake up in the morning inspired by that; their spirit isn’t moved by that. Their spirit isn’t moved by being marginalized, or all that kind of thing. There is something that they aspire to have, to create, to give to someone else. And if you start your relationship with a person by acknowledging what spirit is actually living in front of you, then you’re going to have a different relationship. So, since you mentioned asset-framing, yes and yes.

What I wanted to maybe — to tie it back to the original comment, the schools didn’t discover that I had a high IQ. My mother knew it way sooner, and she advocated for me to get into these different programs my entire early school life, and it was very hard. Folks were not willing to test me; they weren’t willing to consider me in those ways. I don’t know if it was the school system or racially motivated or whatever, but she had to work at it. She had to push at it. The first scholarship I got was to a place called Roeper, and that was a consequence of my mom pushing. And their criteria for even considering me was that I take an IQ test.

So once I get the IQ test and I go to Roeper, and all of a sudden I’m a smart kid now. And so all my toys change — I don’t get to — it’s not G.I. Joe with the Kung Fu Grip anymore; now I’ve got to get science kits and electronic — which I liked, honestly, but I also wanted to do normal stuff. So I’d definitely get nerd toys, and not long after that, the PC comes out and so I get a chance to start building computers, which I really liked, and also programming them. So I’m on the nerd track, in full bloom.

And then, when I was 14, I get accepted to Horizon Upward Bound — again because of my mother’s efforts, not because of any kind of passivity. And then I get a scholarship to Cranbrook, which is a fantastic private boarding school hidden behind cobblestone walls in Bloomfield Hills. And it’s very much like being transported off-planet, because I had lived, up till that point, around poor folk and with what I call “regular folk.” I’d been around regular folk, and Cranbrook is not a regular-folk community [laughs] at all — at all. Very different.

Tippett: One thing that I really appreciate in your — not just in your work, but in how you bring these ideas into different communities — what you are presenting is on some level a critique of the way things have been done.

Shorters: Definitely.

Tippett: You’re not judgmental. And I wonder — and you’re not doing the deficit thing, also, with rich people or [laughs] nonprofit leaders or journalists. And I’m curious, when I think about this time in your life, and, I mean, it’s just so fascinating, because you were, as you said, you were on another planet. But you weren’t that far from home. And so I just wonder if some of this was planted in you in that experience, too.

Shorters: Oh yeah. Oh, definitely. Look. I — just picture this: little Black boy, tech nerd genius, raised in the ’hood — that’s Trabian, OK? [laughs] So the idea that these things don’t have to contradict each other — that’s my life.

Michigan is itself a pretty peculiar state, right? So when you grow up around folks who share kind of this working-class identity even though they come from different ethnicities and races, and then you toss in race and you see the polarity that comes from that — if you pay attention, like Trabian had to, then you develop nuance. You know, there’s no reason to vilify my neighbors and my friends. They see it differently, they feel differently about it, but we end up in the same schools. We end up in the same situation, honestly. And at the end of the day, I really do feel like people who decide to tap into the fear and use the fear as a way of gaining power and of keeping attention, those people are the enemy. Like, if you’re going to figure out who you need to be against, you need to be against folk who are telling you that you have to be opposed to someone you’ve never even met, right? Those are the folk that we should look sideways at.

Tippett: And that’s an interesting way to start talking about your way of seeing and, I would say, teaching, informing, and creating a different kind of cultural conversation and model. And you have such interesting influences that brought you to this work, that also are very defining of our cultural influences and inflection points, including, as you mention briefly, you were a tech kid. Let’s give you credit — this was before nerds were cool, right?

Shorters: [laughs] True that. True that.

Tippett: Nerds are cool now, and they were not, back then. And so you were into coding and hacking. And I love something that you said. You said, “A really good technologist understands that in order to hack something well, you have to understand a system well enough to get it to do something it wasn’t designed to do,” and that that is a skillset you bring to cultural change

Shorters: That’s right. That appreciation is how I’ve tackled everything since. The tech company that we formed was a type of technical hack on an innovation limit that we had encountered. I developed this thing called culture typing, which is understanding which types of change a culture can handle at any given moment. And by “culture” I mean like, a single organization, a business, or the society itself. For me, the combination for understanding systems well and then being able to parse that — can you critical-path the connections here so that, for instance, asset-framing is a cultural hack. It’s understanding how culture works, well enough to use culture to change culture. And so I was taught that culture is the transferable set of beliefs and behaviors that enables a group to survive. It is true of social culture; it is true of music culture; it’s true of bacterial culture. Like, this is what culture is, right?

And so in understanding that, it became very clear that if I’m a Black person, I’m taught to believe that I must deficit-frame my people. I must dramatize the disparity, right? So that’s the belief. And then the behavior is to then stigmatize my people so that I can attract resources, right? If I can define them by their worst threat, greatest inequity, whatever, then I can attract resources. Well, this culture of denigration for dollars means that, yes, you’ll attract the resources, but you do so by writing your population into the public consciousness as inferior, as ineffective, as pathological. All these things are the only ways that people know to know us, because the way that we have been taught to survive is by dramatizing our injustices, which — I think it’s important to point out, the injustices are real. So we’re not saying ignore any of them. We’re saying that is not what defines us. That’s not what defines anyone.

Tippett: And you ended up walking into philanthropy and again grappling with framing and ways in which people and organizations that want to help, want to be of service, actually end up making some of those — colluding and actually catalyzing those moves you just described. The terms that are used about disparities — “disadvantaged,” “impoverished,” “at-risk” — and what that does in the mind of the person who’s trying to be of service and of the person who is on the other end of those descriptives.

Shorters: You mentioned that the way we talk about framing doesn’t feel judgmental. Let me illuminate, at least, why, for me. Number one, everyone who’s in the social impact space wants to make the world a better place. Well, that’s their aspiration, right? So if I’m applying asset-framing, if we’re defining ourselves by our aspirations to make the world a better place, then all these other things, these negative consequences, that’s not intentional. That’s accidental. So I’m not going to beat you up for an accident. I want to show you what is blocking your worthy aspiration. You want to magnify human life, you want people to live more fully, you want folks to have greater opportunity, you want justice, you want freedom, you want all these things, so I just want to show you how the instrument that you’ve been taught to use has a big hole in the bottom of the bucket, right? And if we can recognize that, unintentionally, we end up stigmatizing, and the consequences of that, then we can change the behavior. What I want to do with asset-framing is I literally want to help people who have committed their lives to making it better for all of us to have a fuller toolset and to recognize that you fall into a cognitive trap — not by your design, but once you see the hole, it’s very easy to try not to step into it; to avoid those behaviors.

[music: “con-sanza” by Michael Brook]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today with social visionary, the creator of “asset-framing,” Trabian Shorters.

[music: “con-sanza” by Michael Brook]

One thing I notice, also, is you don’t use some of the language that’s very commonly used around “unconscious bias,” and I’m just curious why. I feel like there’s probably a reason for that.

Shorters: There is.

Tippett: And yes, let’s look at the brain, let’s look at the brain science actually, that you’re relying on.

Shorters: So the main reason is, I made it to college once upon a time, right? And I go home in the summer, I hang out with my boys, and we talk about all the same stuff that I learned in these different classes, except regular folks use regular words. And people who get degrees use a language that nobody knows what the hell you’re talking about. And so asset-framing, as I — I did invent that term for the college class, but all these things around “implicit bias” and “stereotype threat” and all that jargon, we totally understand it, but if you can put it into normal language, then people actually understand what you’re talking about, as opposed to impressing upon them that you’ve studied things that they don’t know.

And even this idea of equity itself, which is — many of the folks who employ us ask us to help them work on issues of equity and engagement and community-building and the like. And so I always like to point out to foundation leaders and corporate leaders, in particular, that every other time you use the word “equity” — financial equity — every other time you use the word “equity” you are literally talking about what has value. And I’m just saying, be consistent. This is also — all of our conversations about equity, they’re all about what or who has value. And if you’re going to start a conversation about equity around people, then you have to value the people at the center of the question.

Tippett: Not about who is a “problem” and who is “disadvantaged,” right?

Shorters: No, that’s right.

Tippett: That’s the way it gets framed.

Shorters: That’s right. All that “disadvantaged,” “broken-down,” “at-risk,” “marginalized” — all those are — that’s language you use when you’re trying to cost-control or risk-control. That’s risk-control language. And I just, I like to point out to folks, particularly the folks in the finance industries, there’s a difference between risk management and equity investing. [laughs] And so if you’re talking about being equitable, then you have to define people by their assets. You’ve got to say, what is it we’re investing in? We’re not investing in poverty. Who invests in poverty? You’re not trying to grow poverty. [laughs] You’re trying to invest in people’s aspirations towards wealth; you’re trying to invest in people’s will to make a better future for their children or their community — those are things that are investable, but not poverty.

Tippett: And would you say a little bit about your understanding of “primary mind,” which is kind of some of the understanding of the mind, the brain, the human condition, that helps us understand why we do this and how to kind of work our way out?

Shorters: Actually, this is huge. So, simple fact of the matter is, your nervous system, your central nervous system, is physically connected to your brainstem. It’s one set of wiring. These are not — it’s not a separate system. They connect. And so the same way that your nervous system is always on, always firing, doesn’t need your permission to feel and to see and to sense; it is always doing these things — the same way that is happening, the other end of that system, your brain, is always on, always firing, always pattern mapping, doesn’t need your permission to do so. And according to the Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, who we quote every time, in our training —

Tippett: And he’s been on the show, too. He’s amazing.

Shorters: He’s dope. I love that guy. So, according to Kahneman, all human beings are prone to disregard information that doesn’t fit the mental picture presented to it by its nervous system. And so the fact that our brains are always pattern mapping means that sometimes you will look at a set of cars in a parking lot, and you can sort of make out the impression of a face on the grill of a car; like, the headlights and the grill of a car sort of look like a face. Or you might look up into the clouds and you see shapes of clouds that look like animals, or like something — what I try to remind people is, number one, you’re not crazy; this is just your intuitive system doing its job. It is always pattern mapping. It’s always saying, this looks like that. That’s what it does. It makes sense of the world for you, and it does it a thousand times per second. It is literally faster than conscious thought, the same way your nervous system. And so, for that reason, whatever patterns it’s primed with are the patterns that it looks for. And so when you only refer to a people a certain way — “at-risk,” “low-income,” “marginalized,” “disadvantaged” — when that’s all, those are the only patterns you’ve fed your brain, it is not your fault that when you encounter such a person, you are primed to think these things. That’s the pattern that your brain has for recognizing who is in front of it. And so those are not choices. Your brain does this instantaneously, literally faster than thought, the same way your nervous system works.

Tippett: I think something I appreciate also, though, that you point out explicitly is that another thing that reinforces it is that since the Enlightenment, at latest, everything in our world tells us that we’re actually rational. And a lot of things are actually organized around the idea that people are rational, even if we don’t behave that way — which I feel like that disjunction is really, like, coming into its own now. But so that it’s not just that there’s this pattern making that’s happening all the time, but we have been taught that the conclusions we reach are rational. And that’s a disconnect with reality. And one way you talked about asset-framing is you’re just — by focusing on letting in the reality of aspirations and contributions, you’re giving the primary mind a fuller set of information to walk around with.

Shorters: Yeah, and here’s what I see going on. We have reached a point where our normal set of kind of cultural and governmental organizational systems, they clearly aren’t adapting fast enough for the realities that we’re encountering. Like, as a society, as individuals in the society, we are creepingly and more and more aware that those in charge are not capable of securing us, right? And of course, that’s innately terrifying. [laughs] But it’s pretty clear, whether it’s pandemic or economic collapse or whatever has happened in the last year, there’s always something that’s proving that we’re not keeping up. And so the reality that we are all, no matter what your race or gender or background, the reality that we’re all dealing with is, the ways that we’ve done things — the culture — the ways we’ve survived must adapt. The transferable set of beliefs and behaviors, the ones we have, are not surviving us, right? So we must adapt.

The simple fact of the matter is, we are literally all in the same boat. We all have the same — well, we all have the same set of aspirations. If you do a cross-section, we overlap in our values and aspirations, like, 90 percent — like it’s really — in our highest values, in our highest aspirations — like 90 percent. It’s amazing how much we overlap. So if we’re going to change our culture, we have to change our narrative. That’s what it comes down to. We have to change the mental models that our brains are using to make sense of the world, because the ones we have right now, they’re failing us — dramatically, you know.

So that’s where, like when I think about our work, I love that this level of instability means we can actually make real progress on racial bias. We can make real progress on gender bias. We can make real progress on economic instability and bias, because the answers that we would’ve given 30 years ago, nobody believes that anymore. [laughs] You can’t convince people of the old path.

[music: “Gullwing Sailor” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Trabian Shorters.

[music: “Gullwing Sailor” by Blue Dot Sessions]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today I’m with Trabian Shorters, a visionary social entrepreneur and the creator of “asset-framing.”

I know you’re doing some work with the Solutions Journalism project, and perhaps with other journalists, and journalists are often, also, very mission-driven people.

Shorters: No doubt.

Tippett: But the forms that have us investigate dysfunction and focus just with such intensity on what is catastrophic and corrupt and failing seem, at this stage — you can look at history and you can see where that led to things being made better, but right now, as you said, there’s all this reasonable despair and fear, and that is deepening it. And something that — I can’t remember if you wrote this somewhere, or said it, but as I was investigating you, you said, “We crave the moral” — and you’re just really talking about at that nervous system–brain level — “We crave the moral direction stories provide.” And I think that is such an interesting way to underscore what is at stake, and kind of a calling to the parts of our society that help us piece our story together.

Shorters: Yes. Well, I use Black racial experience as kind of a divining rod for these conversations, in part because that’s where America — [laughs] we stumble. Whatever we say we believe, you throw Black racial considerations, and all of a sudden we go sideways, right? And so to your point about the role that media plays, I’ve said this to David Bornstein, who is the co-founder of the Solutions Journalism Network, that if there is a sort of narrative of racial hatred in the United States, then the news media is co-author of that narrative and co-conspirator in the cover-up. It’s very easy to understand, from a sociological standpoint, that when the media reports on populations and cities and neighborhoods a very specific and particular way, and never counterbalances that narrative with any positives, then the only patterns that our brain have to draw upon are fear triggers.

Tippett: I think this was from something that Solutions Journalism had — anyway, it’s like, this is the original lede of a story, for example, and it’s just so familiar: [laughs] “The Latinx community in the United States has always been, for the most part, on the bottom half on income, in the American society. The struggle to have access to health and mental care is part of the history; however, the COVID-19 pandemic has come to intensify the problems.” And that’s how it starts; it goes on. And that’s a very familiar way into a story.

And then here’s a revised lede that I think your team took a look at, and it starts this way: so, “Since 2014, Latinx people have constituted the largest ethnic group in the nation’s largest state. They now represent 39 percent of the California population.” And then it goes on to talk about “in recent years Latinx residents have made advances in economic well-being measured by metrics like reduced poverty rates, growth in business ownership.” And then after a couple of sentences like that, people elected to school boards, local offices.

Shorters: Yeah, they’ve made progress at everything except for this.

Tippett: And then, “Despite this impressive social and economic progress, Latinx residents have lagged behind other Californians in achieving important goals like home ownership and income growth, and we can now add to that list the disproportionate harm visited on the community by the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Shorters: Now, with that example, that was the California Healthcare Foundation, I believe.

Tippett: Oh yeah, right. But you’ve worked with them.

Shorters: Yeah, we had trained and consulted, and then they …

Tippett: Then they learned to do this.

Shorters: … they applied it. They applied it. And what I want to underscore in those two different ways of framing — all the facts were accurate. Nobody made anything up. Both framings are true, right? So we didn’t have to invent anything. The first framing, however, about how Latin American folk has always failed in these ways, that framing totally left out all the assets, all the aspirations, all the kind of — it characterized them, literally, without value. The asset-frame version started with their value, yet still told you about all the ways that they’re not where they want to be. So that’s why we suggest to journalists, it is more accurate and honest reporting. When you’re going to tell the story where all you do is point out what’s broken, but you don’t point out what’s working in a culture, well, recognize you’re inclining people to think that all that exists about that culture is brokenness. They didn’t come up with that conclusion on their own; they came up with that conclusion by your reporting. And so that’s what I mean by journalism ends up being a co-author.

Tippett: And you point out that, of course, so yes, the deficit-framing is affecting the people who are hearing this, how they’re — I mean, really, what they’re taking about how they’re looking at the world and looking at certain people. I was recently — I kept thinking about this when I was getting into speaking with you, was two Black men in New York City, who are both brilliant and extremely successful. And they were talking about how upsetting it is for them to hear this language — which I think has been coined to, again, to be of service, the “school-to-prison pipeline,” which is like, a rallying cry for making something better. But they said, what effect does that have on …

Shorters: Exactly.

Tippett: … Black young people in those schools that are defined as — yeah, go on.

Shorters: Well, just — so again, let’s look at how deficit-framing has unintended consequences. So I agree with the idea that saying “school-to-prison pipeline” suggests that some populations are born on their way to prison. Now, just think about that for a second, because that’s terrible. No one is born “on their way” to prison. That’s a terrible way of thinking about a life. All right, so number one, I understand the objection to “school-to-prison pipeline.”

But let’s drop back 30 years. In the ’80s — I was alive then. I remember when there was this dramatic uptick in violence in cities and neighborhoods, and John Dilulio had put out his study saying that there was a “super predator” emerging in our urban centers, young people who are born Godless and moralless and violent, and they happened to be Black and brown, right? And so in the ’80s there was this fear, again, generated. And the media liked to tell those stories. So now there’s this idea that a monster is coming from the ghettoes and from the inner cities, or whatever; so there’s this feeling that there’s a monster being baked. And in response to that fear, both liberals and conservatives pass more restrictive policies, including the idea that any child who brings a weapon to school will be expelled. “Zero tolerance,” they called it.

Well, zero tolerance for weapons in these schools, over time, morphed into zero tolerance for any behavior that we don’t like, and these policies were disproportionately reinforced on Black and brown kids, which led to them having extended periods of time out of school, which leads to truancy, which created this thing that some marketing group started calling “the school-to-prison pipeline.” Trayvon Martin was, of course, expelled under one of these zero tolerance policies — not for weapons, but for something minor that he had violated in school, at the time that he was killed. So when you deficit-frame, your solutions end up creating problems that you have to fix later. We built the thing that we’re trying to solve now.

If we had a different orientation towards our students — if we had defined them by their aspirations to graduate, their aspirations to contribute to society, to fulfill their own dreams, if we recognize that inner-city children still aspire, if we recognize that poor kids still contribute, then we would look for ways to move the systemic obstacles to their abilities to do so. And that goes well beyond whether or not they can bring a weapon to school.

Tippett: So let’s talk about the BMe community that you’ve created. Just talk about that, because that feels like that’s where — it’s one place where all of this comes together that you’re …

Shorters: No, I appreciate you giving me the opportunity to talk about BMe, because in a lot of ways it’s a culmination of the other things that I’ve studied or learned in my life. I mentioned before that the question that we all have to answer when we look at each other is, who do you think we are? And so here’s the function of BMe Community. In my own email tagline I call BMe Community “leaders who speak life.” We have enough sources telling us what’s broken. We have enough sources telling us what needs to be fixed. We have enough people giving us constant fear triggers, fear primers, right? We have exhausted people on what they should be afraid of and worried about and scared of. The CDC has reported that news consumption is a health hazard, right? [laughs] [Editor’s Note: The CDC has recommended taking breaks from watching, reading, or listening to news stories, especially in the time of COVID, as a way to cope with stress.] We’re stressing ourselves out. Like, it’s crazy.

Right now we’re in a society that is awash with fear triggers, so much so that we think it is the only way to motivate and engage people. And it is not. And what we’ve seen in BMe Community and what we’ve seen with asset-framing is when you learn the skill, when you learn how to asset-frame — I’ll bring it back to BMe, but this is the broader point. When you learn to asset-frame, you literally engage more people, have higher impact, make people more willing to do systems change, and raise more money. We’ve shown that all these things happen when you learn this skill. So the thought behind BMe Community is, why don’t we gather the Black leaders who show up in communities, are trusted in the places where they work, go unrecognized and unsung because the public narrative isn’t interested in this generative, positive stuff — they only want to hear about the worst things?

So we know there’s an entire population of builders who were in these neighborhoods and communities before protests ever happened; they’ll be there during the protests; they’ll be there after the protests. They are constantly feeding people’s lives. They are constantly helping people to live. They are constantly helping people to own. They’re constantly helping people to realize their voting rights. They are constantly helping people to excel. There’s a whole infrastructure of builders, of doers, of people who love and care, that gets totally ignored because they don’t fit the cycle.

So we’re like, well, why don’t we gather those people into a community? Why don’t we acknowledge them? Why don’t we resource them? Why don’t we reinforce them? Why don’t we let their love build, and then engage them with anybody else who wants to be a part of a generative agenda? If half of our social impact work is about fixing broken systems, then the other half of our social impact work has to be about building high-functioning societies, right? Better cultures. And so that’s what BMe Community is about. BMe Community is Black folks building upon Black love to make a better society for everyone.

[music: “Delion” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today with social visionary, the creator of “asset-framing,” Trabian Shorters.

[music: “Delion” by Blue Dot Sessions]

So I want to — we’re going to have to circle to a close in a minute, but before we do, I would love to just go through, again, for just that person out there who does whatever they do, in whatever kind of institution they’re in, whatever kind of work they’re in, or community, how to practice this skill. So I made a lot of notes. This stuff is very pragmatic, and some of it is quite simple, if not necessarily instinctive. So how would you — what would you give as some of those bullet points?

Shorters: Sure. First of all, recognize that asset-framing is not about what you say about people. So if you can accept that, it’s not at all about word choice. Asset-framing is about what do you think about the people. So, rule number one, it’s about what do you think about them. Are you introducing them by their aspiration or their contribution, or are you introducing them by something else? Is your first thought about them one that affirms the spirit of the person in front of you?

And when you develop that —

Tippett: So what I was going to say, so that first move is actually internal work, inside yourself.

Shorters: It’s all internal work. [laughs]

Tippett: That’s internal …

Shorters: It’s all internal.

Tippett: … that you get yourself centered, and you talk to yourself.

Shorters: Look, honestly, Krista, I’m being 100 percent — and I invite anyone listening to take the 100-day challenge and see if I’m right or wrong on this. Honestly, when you start practicing asset-framing, your life gets better. You feel better. You see more life, you see more light, in your day-to-day. You’re more forgiving of people who have faults and flaws in your own family.

And then the litmus for how you think of people is, are you introducing people by their aspiration or contribution? And remember, framing: how you introduce a topic frames the topic. How you introduce a subject frames the subject. It’s just about, how do you introduce it? So you don’t have to ignore anybody’s problems or faults or any of that. But you never start with that. You always start with their aspirations; you always start with their contributions. So that’s two.

Three is, actually think about what is obstructing their aspirations and contributions. And the reason why I throw in bullet three is because I don’t want anyone running around saying, Oh, asset-framing is just focusing on the positives. I’m like, no, no. By definition, you must think about challenges. If you’re not including the challenges, you’re not asset-framing. And the reason why it’s so important to include the challenges is because if you just try to focus on the positives, then you’re going to ignore or diminish or negate the legitimate, systemic obstacles that people have. So we’re not trying to say, Everybody aspires to be free and happy, and so, therefore, there’s no work to be done.

Anyway.

Tippett: Well, there was someplace where I saw you do this with the phrase “at-risk,” “at-risk kids,” and you said, OK, what are we talking about? You’re talking about students, right? So, you said, talk about them as “students.”

Shorters: Yeah. In most cases, “at-risk youth” go to school; not all, but most. And so if you talk about “students” and what their aspirations are — even if they just aspire to graduate, right? — “Students who want to graduate face these obstacles” — then people are much more inclined to say, Well, wait a minute, why should any kid have to deal with systemically underfunded schools, systemically overpoliced communities? Why should — if this kid just wants to graduate, grow up, and contribute to society, why do they have to do it with this level of barrier? And when you asset-frame instead of using this sort of deficit-framing jargon, when you define the student by their aspiration to grow up and graduate, then the unjustness of the obstacles becomes easier to appreciate.

Whereas when you talk about an “at-risk youth,” well, here’s the funny thing about an “at-risk youth” — and the FrameWorks Institute has shown this. When you use terms like that over and over and over again, people don’t think about being at-risk as a circumstance; they think about it as an identity, and they believe that “at-risk youth” are born on their way to prison. They’re the ones attending the “school-to-prison pipeline.” And again, from an intuitive level, the causation just attaches to the kid: they’re at risk because of some choice they made or their parents made; it’s not a systemic problem, it’s a “culture of poverty.” That’s on them, not on — right? And so all that language makes it easy to scapegoat. It makes it easy to dismiss people who are experiencing a disparity, as if they are the cause of their disparity, which is ridiculous.

Tippett: I think this is something from the materials that Solutions Journalism used or that you helped them — “Poverty, for example, is a state, not a trait.” But you’re pointing out how easily our minds make that shift.

I saw this event you did for Aspen Institute, where you asked people to turn to their neighbor and just think about — just look at their neighbor, possibly a stranger, possibly someone they know, and just think about, as much as they could, that is wrong this person. [laughs] And that’s an exercise that just reveals how absurd this is, this whole way we’ve been living. [laughs]

Shorters: Yes. By the way, may I, Krista, share that part of the reason why I do that exercise is twofold. One, your intuitive system is the “fast” system that Kahneman talks about, but it’s also — like I said, your nervous system is wired to your brain, so when you get a gut feeling, it is because it is part of the neurology that connects your brain to the rest of your body. And so part of the reason why I give that example is to point out to people that on a gut level, you know it’s wrong to do that. It feels bad, when you have to do that and someone can see you doing it. When you’re looking right at them and you have to think — try to notice everything that’s wrong with them, inside, you go, Ugh, I don’t like it. Right? And so I like to do that exercise to illustrate to people, in your spirit, you know that’s not the way to do it.

Tippett: I do get a sense that the hacker in you has a lot of confidence that this is a shift — I’ve heard you say it, that we can flip the script in a short period of time and that new generations actually do have the capacity right now to change this narrative at scale.

Shorters: Well, let me maybe contextualize that a little bit. The baby boom generation, the civil rights generation, those folks have been adults for 50 years. Everything about our sense of policy and priorities, everything about our culture, has flowed through one generation for half a century. And they’re aging out of institutional power. So as we experience that instability, the other thing that’s going on simultaneously is the most diverse generation that we’ve ever had is becoming the mainstream. And that is why they’re going to fundamentally challenge whatever existing narratives around what a gender is, what women’s roles are, who is Black or white or whatever — even the way we think about race — how fluid those definitions — they’re going to challenge all that, because it doesn’t fit their experience.

So this is it. [laughs] This is the last time that one racial group can carry the majority of this democracy. And in that type of democracy — when you have racial pluralism, where there is no majority — then the skills to be able to see each other’s value becomes a functional skill. It’s not a nice one to have; it’s the only way to govern.

Tippett: The question of what it means to be human is vast, and it’s kind of the operating question of my work. And I feel like the work you’re doing is just so richly informing a 21st-century reexamination and opening up of how we live that question. And if I ask you what you keep learning, through this life you have, this work you do, about what it means to be human, how would you start talking about that, just today?

Shorters: Yeah, well, I’m going to go back to the old guy again. My grandfather, he was a wise dude, and very simple. All of his stuff was very practical, but then when you stop and think about it, it’s deep, you know? And I always loved that whenever my grandpa would say, “Well, you know, in the real world …” blah blah blah blah blah, like whatever came after that, right? But here’s the thing. Anytime he said “the real world,” he was talking about spirit life. Your spirit life is the real world, as far as he was concerned, and everything else we do is an expression of what’s going on in our spirit life. And so I love that his orientation, and my grandmother’s orientation, to people was the spirits that live through us. You will live and die, but the spirit will endure.

And so the question then becomes, what is the spirit that you want to feed? That’s it. Who do you think you are? Whatever you feed will grow. And so if you want to believe in justice, be just. I mean, I’m sure there must be some wise people who’ve said this somewhere. But you get the idea.

I do not subscribe, and for any of your listeners who may be Black, I have never once subscribed to this notion, “It is a white man’s world.” I’ve heard people say those things — “in a white man’s world.” I’m like, what are you talking about. [laughs]

And my grandmother — I do tell this story in the fellowship all the time, but I’ll — there’s a passage in the Bible that gets quoted a lot that says “to humble thyself before the Lord.” But Irma Lee, who’s from Louisiana somewhere, church lady, my grandmother — Irma Lee translated that to me, long ago, and I never forgot her way of saying it. She said, yeah, it says “humble thyself before the Lord,” the creator of everything — you must be humble in God’s presence. But to God’s creation? You’re not supposed to hide your blessing and your faith and your love under a rock. No, no, no, no, no. Humble thyself before the Lord. But for everybody else, shine. Right? So they can see a path.

Tippett: Well, I think you embody that. I feel like there’s such audacity and pragmatism to — something I saw you describe this work, which — “develop a more inspiring and accurate and fundamentally different narrative about humanity, and engage people accordingly.”

Shorters: Amen.

Tippett: I think your grandparents would be proud. Thank you.

Shorters: Thanks, Krista.

[music: “Murmuration” by Go Go Penguin]

Tippett: Trabian Shorters consults widely and is the founder and CEO of the BMe Community. Learn more at bmecommunity.org. He’s also co-editor of the book Reach: 40 Black Men Speak on Living, Leading and Succeeding.

[music: “Murmuration” by Go Go Penguin]

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org;

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org;

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives;

and the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections