Vivek Murthy and Richard Davidson

The Future of Well-being

What if the future of well-being is about “tipping the scales in the world away from fear and toward love”? And what if it’s a surgeon general of the United States, Dr. Vivek Murthy, who talks this way? Krista draws him out with his friend, the groundbreaking neuroscientist Richard Davidson. Together they carry deep intelligence and vision from the realms of science and public health, expansively understood. They explore all we are learning to help move us forward as a species. This conversation was held as a live Zoom event, sponsored by the Center for Healthy Minds.

Image by Andrea Ucini, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

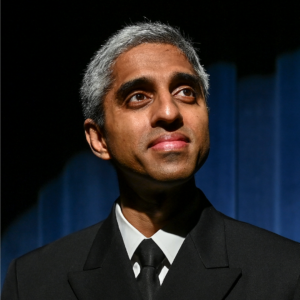

Vivek Murthy is the 21st Surgeon General of the United States. He also served in this role from 2014 to 2017. He hosts the podcast House Calls with Dr. Vivek Murthy. And he’s the author of Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World.

Richard Davidson is the William James and Vilas Research Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He founded and directs the Center for Healthy Minds there, and was the Founding Director of the Waisman Brain Imaging Lab. He is also the Founder and Chief Visionary for Healthy Minds Innovations, a non-profit that translates laboratory science into real world tools. He is author of The Emotional Life of Your Brain.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: What if the future of well-being is about tipping the scales in the world away from fear and toward love? And what if it’s a surgeon general of the United States, Dr. Vivek Murthy, who talks this way? I engaged him, together with his friend, the groundbreaking neuroscientist Richard Davidson.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

This conversation was part of a Zoom event hosted by the Center for Healthy Minds. Richard Davidson, who everyone knows as “Richie,” welcomed the online audience, and I offered an introduction.

Hello. It’s such an honor and a pleasure to be here. If any of you have listened to me or read things I’ve been writing over the last few years, I have so often used these words. I have said, you know, as we walk beyond what we’ve been living through, we have a world to remake. And so, of course, I had to say yes to this invitation, to this event called “The World We Make,” and in the context of drawing out Richard Davidson and Surgeon General Vivek Murthy and their deep intelligence and vision from the realms of science and public health, expansively understood, about the agency we have and how we are learning about the [agency] we have to grow and shape our minds and our bodies and our presence, in and to the world.

It’s such a strange and hard and fascinating time. We are called to be part of so much healing and so much growth, and at the same time, we are learning a great deal that can help move us forward as a species. So I think that is my audacious vision for what we’re going to — the ground we will traverse in this next hour. So. I also want to encourage the two of you to speak to each other. This will be a conversation.

And I’d like to start with the language of well-being. That is kind of a primary concept. It’s a word and a phrase that is used a great deal by the two of you. It’s relatively new in our life together, and really, we are having these rapidly evolving, cathartic shifts in understanding the fullness of what that means and can mean. And I would say that you have both lived through those cathartic shifts, and also been part of them. And I’d like to start with just asking, you know, thinking about that language of well-being, what understanding of that did you inherit or imbibe, growing up and in the early training you had in your fields? And what has that phrase come to point at for you, now?

Vivek Murthy: Well, first, let me say what a joy it is for me to be here with both of you. You know, I have such deep admiration for both of you and the work you’ve done and the immense contributions you’ve made to society. I’ve learned from both of you over the years and just feel very blessed and privileged to have this chance to converse.

You know, well-being — it’s an interesting question you ask, Krista. I think that my earliest teachers in medicine and in life were my parents. And they didn’t use the word “well-being,” but they conveyed a concept of what well-being was, to me, when I was very, very young. And what they helped me understand was that it wasn’t just enough not to be ill, but that there was a whole spectrum on which we could live and operate. And part of thriving in life, according to my mother and father when I was a child, was doing the things that allowed you to function on the highest end, if you will, of your scale, where you were being who you were, enjoying life, contributing to society.

And as I got older — it’s interesting; I went to medical school, I trained as a doctor — the concept of well-being didn’t really come up very much. We were — it’s felt, in training, we were very focused on identifying and eliminating disease; an important endeavor, no doubt. But it felt like half of the story. And the other half, about how to optimize our sense of well-being, if you will, that was not so much the focus. There weren’t words for it. There wasn’t an approach for it. There wasn’t science and data that we talked about and reviewed in the classroom.

But I will say now, in finally thinking about not only my life now, but thinking about the responsibility that I’ve been privileged to take on, to think about and to do everything I can to support the broader health of our country, I think about well-being a lot, because I think we have an opportunity to really see health in its broadest sense; to redefine public health, not just as the absence of disease, but really as the endeavor that we all need to undertake to cultivate our ability to live at the top end of our scale, if you will, and through that, to not only enjoy life and contribute the most to the people around us, but to contribute, also, to society in the way that can move all of us forward and help us get through very difficult times, like this pandemic.

Tippett: We will pursue that further. So Richie, well-being: what understanding did you inherit, and how has that evolved?

Richard Davidson: Yeah, I love that question. And I’m finding that I’m spontaneously recalling events from my childhood. My father was a businessman, not connected in any way with academics. And I remember times when — the details aren’t what’s critical here, but situations where he was in a business relationship with someone, and I remember very distinctly that there was an agreement to — these individuals were not able to pay for something that had been agreed upon, and I remember my father working out some kind of barter arrangement.

And there was a transmission of kindness in that process that I very distinctly and somatically experienced. I still can envision a slight tearing in both of our eyes, as this transaction was unfolding, and I was a witness to it. And so the element of human connection, which I’ve learned so much from Vivek about, was so palpable. And this, I think, provided the seeds. I didn’t have a language for it at that time, but it kindled in me the quest to understand the mind and the heart that has been a lifelong quest.

And then when I was a student, particularly when I was a graduate student, I was trained very much in the way that Vivek was describing. I was trained to, when I look at people, to try and discover what is wrong with them.

Tippett: Right; a focus on dysfunction.

Davidson: Yes. And now, when I look at people, I have retrained myself to look at people and to discover what’s right with them, and it’s a very different orientation. And I think that one of my aspirations is that we can learn from this pandemic the qualities that we can nurture to help us, going forward, in a way that will build our resilience so that when we encounter adversity again, we will be equipped with the tools of well-being that will enable us to navigate these challenges more smoothly.

Tippett: And, you know, you and I have spoken before about how the — I mean, you were right at the beginning of the field of neuroscience. I mean, neuroscience as we know it now did not exist, when you entered your career. There was no brain imaging. The ways we’re learning on this frontier are very, very new. And even, Vivek — I mean, Western medicine, the medicine of the 20th century — you point at this a little bit — is, you know, really has only been learning to acknowledge the interplay between the physical, the mental, the emotional, the spiritual; in fact, that our bodies are all interplay. But we haven’t known that, scientifically, until very recently.

Murthy: Well, Krista, I think you’re right; I think that there has been a tremendous amount of discovery in recent years, in medicine. But you know what’s interesting to me is that, if you look in scripture and if you look at teachings over centuries, I find that that understanding has always been there …

Tippett: It was there, yeah.

Murthy: … this notion that our heart and our head and our soul, that there’s a beautiful interplay between them, and not this stark separation that we seem to read about in the textbooks over the years, in medicine. And so, you know, I do think that in some ways, medical science is catching up to an intuition I think that people have had over centuries. And I think it’s a very exciting time.

But I think it’s also very important that it’s happening now, because the truth is that we can’t fully optimize our well-being, we can’t understand how to build a foundation for good health, if we don’t understand the interplay between our mental health, our physical health, our spiritual health. And some of these, I think, in the world of public health, we sometimes have some shyness or difficulty talking about, spiritual health being one of them, which I think of as — and when I think about the conversations I’ve had with patients over the years, so many of them have leaned on their spiritual traditions, whether they have a named religion that goes with it or not — they’ve leaned on those spiritual traditions for support, for insight, for energy and healing, during difficult times. And I think the more we’re able to talk about that openly and explore these sources of strength, I think the more readily we’ll be able to improve and enhance well-being, in our country and around the world.

Davidson: And if I can just add to that, I think that the discoveries in modern medical science, neuroscience, biobehavioral science, has helped us to understand more of the details of how well-being is embodied. And so when we think about well-being, it is not simply an ephemeral psychological state or condition, but it very much is intertwined, as you say, with our, all the organ systems in our body in ways that have demonstrable consequences for our physical health. And so the opportunity to cultivate well-being is not simply an opportunity to cultivate these subjective qualities, but it can potentially have a profound effect on our physical health, as well. And this, I think, is one of the really exciting issues that is on the horizon now.

And I think the understanding of some of the mechanisms through which these interactions occur has enabled well-being to penetrate into mainstream, rigorous science in a way, today, that it has never happened before. In fact, during Vivek’s first term as surgeon general, we began to talk about bringing well-being to the National Institutes of Health. And just very recently, the NIH has funded six interdisciplinary networks on well-being to help launch this as a serious scientific endeavor. And we are part of that, and Vivek’s voice is very much an inspiring one that helped to bring this about in the first place.

Tippett: That’s wonderful, and it’s the kind of story we don’t necessarily hear. And, you know, I’ll say, I mean, what a dramatic time we’ve been living through and are living through still. It has struck me, through these experiences we’ve had, that the official media and public analyses and narratives tended to focus around a pretty limited frame of well-being, right? Like, we were very fluent in health, certain kinds of health metrics — illness, death — and also, in economic losses.

You know, one of the, I think, single most helpful conversations I had in the last year was with Dr. Christine Runyan, who spoke about the nervous system to me, about what’s been happening in our nervous systems, and not just with the pandemic, but with social isolation; and how our stress responses, individually and our communal stress response, was set in motion in March 2020, for most of us, and then has been on overdrive ever since, and the cascade of consequences that that has that do not all manifest as physical illness.

So I’m just curious, giving you that, framing it that way, I’m curious, what would you like to, how would you like to fill out and expand what we’re looking at, what we’re seeing? And I guess that’s also a way of saying, what are you looking at? What are you seeing that is bigger than that narrative?

Murthy: That’s such a rich question, Krista, and there’s so much to say there. But I think a couple things I think that are worth underscoring in what you said, which is that there are profound, invisible prices that we have paid, wounds that we have sustained during this pandemic. And we talk about what’s easy to see and measure — number of hospitalizations, cases, deaths, number of schools that have had to close, number of people who lost their job — these are very important consequences. But they are part of a broader set of consequences, which include the impact on people’s mental health, on their identity and sense of self, on their sense of connection to other people, and on their sense of purpose.

And I think one of the profound things that has happened during this pandemic is, I think it’s given people a moment to rethink a lot of things in their lives. Now, everyone has experienced this pandemic differently, but the vast majority of us have experienced it deeply. And that’s led, as many other profound moments do in our lives, to, I think, a rethinking for many people. For some people it’s been about their work and questions of do I find real purpose in what I’m doing? Am I supported, in terms of my well-being, at work? Do I feel I belong, in my community at work? Do I even have a community at work? And for other people it’s about their family and where they live. I’ve lost track of the number of people, Krista, that I’ve spoken to, who have decided that they are going to move to be closer to family and friends, as a result of this pandemic experience.

You know, in these ways and in many others, I think many people are asking themselves, Do I really want to go back to 2019, or is there a better version of 2019 that would allow me to be happier, healthier, and more fulfilled? But this is, I think, a window of opportunity that we have for reflection and for action, that I don’t think will remain open forever. You know, there’s a certain point after which, I think, that window closes and we resign ourselves, for better or for worse, to going back to the way things were pre-pandemic.

But to me, the silver lining here is, can we do better? But the only way we do better is if we’re able to confront and talk about some of these invisible costs. It’s actually one of the reasons why, when I, you know, when I took this job to serve as surgeon general during this moment, what was on my mind were these invisible costs. And I remember speaking, you know, with the president before I was sworn in, about this, to say, Look, if I — you know, one of the things I really want to do in this job is not only help us to get through this pandemic, but to really think more deeply about how we do better when it comes to mental health, about how we have a broader conversation as a country, about well-being and how we reflect that, not only in the decisions we make in our lives but how we design our schools, how we design our workplaces, and what we think of as success, when it comes to public policy — not just the dollars and cents of it, but whether or not policy contributes to a sense of well-being.

Tippett: Richie, what’s been missing for you, and what are you hoping to inject, in this window that’s ahead of us?

Davidson: One of the things that for me is a really interesting issue to consider is, this pandemic I think has taught people how malleable we are, how susceptible to change we are, and it has underscored plasticity. Now, I often say that plasticity is neutral. It can be harnessed for the good, and it can be harnessed for negative consequences. And —

Tippett: And let’s also just, for people who aren’t familiar with your contribution to our use of the word “plasticity.” I mean, your science has in part been on this frontier of understanding that, contrary to what you and I were taught when we were growing up, our brains don’t stop forming, we don’t stop forming as human beings at some point; and that we actually have agency to change our brains, to change our bodies, to change our character; and that all of that is interwoven. I think that plasticity, it really was a discovery, I think; is one of the most exciting discoveries of my lifetime.

Davidson: Yeah, it is such a powerful insight, and it’s an insight both about the brain, as well as the way our systemic biology works. We know that the regulation of our genes, epigenetics, the science of how our genes are regulated, is very much influenced by many different factors, including our social experiences, our demeanor, our emotions; and all of that can be harnessed for the good. And a lot of the time, this plasticity is being hijacked, if you will, by forces around us over which we have very little control and often of which we are only dimly aware. The kinds of actions that Vivek was describing are intentional actions that we can be taking that can promote plasticity in a very positive way. And so I think that if we can take from this tragedy of the pandemic this insight about the significance of plasticity and harnessing it for our own well-being, I think that it will really have long-term beneficial consequences.

[music: “Inessential” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Richard Davidson and Vivek Murthy.

[music: “Inessential” by Blue Dot Sessions]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, I’m with the renowned neuroscientist Richard Davidson and U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy. We’re exploring the evolution of well-being and public health in the light of the times we inhabit, and the understandings we’re gaining, from neuroscience to medicine.

This time is bringing people to very existential questions and to really, really being serious about that question, How do I want to live? What matters? And to bring in plasticity, what you have been showing us and others have been showing us — that we really can radically change — is a wonderful conjunction.

Davidson: Yes. And the science actually shows that it doesn’t take that much. We can see change in certain contexts, with really minimal kinds of interventions, which speak to the power of plasticity for making meaningful change.

Tippett: You know, Vivek, before 2020 you have long been speaking about a public health crisis of loneliness. And that was preexistent. And then one of the many dynamics, but a very significant, life-changing one, was we were all kind of forced inside, and also inside ourselves. You’ve spoken about how you — very compellingly, about how after your first term as surgeon general you did a lot of interior reflection and gained a lot of self-knowledge; that there was grappling that happened. And when you talk about strategies for loneliness, one of those that I think might have seemed counterintuitive to many but might make more sense now, is to embrace solitude. I’m just curious about how you’ve continued to reflect on that in this time.

Murthy: Well, Krista, I mean, certainly I think you’re right that this moment has forced people to dramatically change their social interactions with one another. But one thing I think was true before the pandemic and remains true is that we all need a certain set of high-quality connections in our life, and we all also need some solitude in our life. And I think that the culture that we live in is actually a very extroverted culture. It can make introverts feel like there’s something wrong with them. I say that as somebody who is an introvert myself. I think you’re absolutely right that we don’t really learn how to cultivate and to enjoy those moments of solitude, especially, interestingly, now, in the modern age, where we have devices that can fill in all the cracks and crevices in terms of time, in our lives.

Tippett: Yeah, they’re constantly taking us outside ourselves.

Murthy: They are. They are. And they also create the illusion that we never have to be alone. We never have to be by ourselves. There’s also, I think, a lot we can do in moments where we are not able to see one another in person, that the pandemic also helped us understand more clearly. So, for example, being able to spend just 15 minutes a day with other people, even if it’s on video conference, as long as it’s time with somebody that you know, that you love, that you have a good relationship with, where you’re being open and honest — that is very, very powerful. It’s — a little bit of time can have a profound impact on our sense of connection, because we were designed to connect to one another.

The second thing we realized can really help is giving people the benefit of our full attention. You know, we live in a world where our attention is so extraordinarily fractured; fractured, in part, by the devices we carry in our pockets. But, you know, I will admit that I have been guilty, on a number of occasions over the years, of having a conversation with a friend while I somehow find my hand reaches in my pocket, pulls out my phone, and I’m checking my inbox, or I’m looking at the latest score of a game, or I’m sorting my mail while I’m talking. And I’m doing all this because I convince myself that I can pay attention to multiple things; I can multitask. It’s one of the great myths and falsehoods that we tell ourselves. But giving people the gift of our full attention is what makes conversations so extraordinarily fulfilling. It’s what can make the, really, the difference between 30 minutes of time that flew by and you don’t really know what happened, versus five minutes of just deep, deep connection with another human being.

Tippett: Yeah, that quality in focus, of presence.

Richie, I feel like that’s not necessarily the way Center for Healthy Minds talks about what you’re teaching people, but it is actually a byproduct of all of the techniques and tools that you offer that, whether it’s schoolchildren or adults or people who are in distress — it’s becoming at home in oneself in a new way. And a consequence of that, I think, is being able to be alone, peaceably …

Davidson: Yes —

Tippett: … which then affects the way you are with others.

Davidson: Yes, absolutely. I, first, I think that the way that Vivek put it is very much how we would also describe it. During the pandemic, I think that we know from both the research that we and other colleagues have done, as well as experiences of actually doing this, that really simple exercises — for example, one is appreciation. Appreciation is a quality that is, unfortunately, not very well appreciated. It is something that’s so accessible. And when we reflect on our challenges during the pandemic, it doesn’t take a lot of thought to recognize that no single person could navigate this alone. We so critically depend upon others.

And one of the things that we often recommend to people is to reflect on one’s daily life and regular activities. One that I often use is eating. If we reflect on all of the individuals that have contributed in one way or another to enabling us to have food on the table, and allow the sense of appreciation to arise, it can be so beneficial. And even formulating in a more explicit way, how you might thank a person when you next see her or him, to express your appreciation, your gratitude, this is something that is an elixir for the soul.

And even during these times of being isolated, physically isolated, I often have said that I think, in the early stages of the pandemic, I wish we would’ve chosen the term “physical distancing,” rather than “social distancing,” because we can be socially connected even in solitude. And I think this is a point that Vivek was making, and certainly the research really bears that out. And if we do these simple little exercises on a daily basis, it can be so beneficial.

You know, I often remind us that when human beings first evolved on this planet, none of us were brushing our teeth. And I’m sure every listener here brushes their teeth at least a few times a day, and this is not part of our genome. This is something that we’ve learned to do because it’s good for our personal, physical hygiene. And what we’re talking about is also good for our physical and our emotional and our spiritual hygiene. And I have this strong conviction, from everything that we know, that if we engaged in these simple kinds of exercises for even as short a time as we spend brushing our teeth each day, this world would really be a different place.

Murthy: Krista, can I actually just add on to what Richie so beautifully said? I think, you know, in a modern society that is hyper-obsessed with efficiency and with using every moment, I think this is what’s really striking to me about well-being. Like so many of the pillars of well-being that Richie and his team have so eloquently written about — the pillars include insight and purpose and awareness and connection — these don’t necessarily require hours and hours a day. You know, sometimes it is simple moments that can generate so much benefit, because again, I think our bodies are actually, and our minds, are hard-wired for connection, for well-being. We just have to feed it just even a little bit.

But I was also thinking about what you said earlier, Krista, about learning about ourselves by being comfortable with ourselves, connecting with ourselves. That is so extraordinarily important, but not an area that we focus on, right, when we think about a child’s education and what they need to know to be happy and successful in life. You know, today, earlier today, we had a parent-teacher conference for my two children. They’re five and three-and-a-half, Teyjas and Shanthi. And it was very interesting. The teachers asked us, they’re like, So, what are your goals for your child in school? Initially, I found myself racking my — and being like, OK, well, do we want them to focus a bit on reading? Do we want them to focus on like, social interaction? What do want them to really focus on? And it was only after I hung up the phone that it struck me that actually, the most important thing I want for them is to be comfortable with themselves, is to be comfortable in their own skin.

There’s this beautiful poem, which I suspect both of you know, by Mary Oliver, called “Wild Geese,” where the first few lines really remind me of this. You know, she says, “You do not have to be good. / You do not have to walk on your knees / for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting. / You only have to let the soft animal of your body / love what it loves.”

And that is so simply put, yet so elusive, I find, in society which tells us to chase many different things, right? And whether it’s good grades and a résumé, in school, or whether it’s wealth, power, and fame, which is, I think, the three big goals that society tells us constitutes our self-worth. But this pandemic, for me, has made me rethink a lot of things. But one of them is, what are we seeking to give to our children through their education, both in school and out of school? How can we best give them the best shot at living a healthy, fulfilling, and happy life?

Tippett: It’s so stunning to introduce those lines of Mary Oliver, because it — I would say one effect of the pandemic, also, especially in that early period, was that we were forced back to this realization of the soft — right? — the soft animal of our bodies; that we are all that; our creaturely existence.

[music: “Delion” by Blue Dot Sessions]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today with U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy and neuroscientist Richard Davidson.

[music: “Delion” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Richie, I’d love to go a little bit deeper into the “four pillars of well-being” that you’ve worked with, with the Center for Healthy Minds. I think you were kind of wandering in there, but I’d really like to delve into it. And I know that you also have practices, as you said, and you have “micro-practices,” which is — you know, I greet that word with relief — not heroic practices, micro-practices that can be woven into the fabric of our days.

Davidson: There’s a lot to say about the micro-practices. We think of it as micro-interventions, or even the microdosing of well-being, if you will. And research clearly shows that it doesn’t really take much to activate these parts of our mind and our brain and our heart, and as Vivek says, we believe it’s because this is our true nature. And so we can tap into this nature, really quite easily.

So to go through the four pillars, the first pillar we call awareness. And awareness is typically not regarded as a core feature of well-being, and yet research shows that showing up and being fully present in the way that we discussed earlier, the way that Vivek beautifully put it in the early part of our conversation, is so much at the heart of well-being. One component of awareness that scientists have spent a lot of time studying is this quality that we call meta-awareness. Meta-awareness is the capacity to know what our minds are doing.

That may sound a little bit strange, to some, but how many listeners have had the experience of reading a book where they may be reading each word on a page, and after one or two pages, they realize they have no idea what they’ve just read? Their mind is somewhere else. It’s lost. And the moment they recognize that is a moment of meta-awareness. And that turns out to be a really core element of well-being.

Tippett: That you are aware that you are aware.

Davidson: Exactly. And a very famous study that was published now about a decade ago found that the average adult — this was a study done with about 3,500 people across different parts of the world, so this was not just Americans. And the study found that, on average, the average adult spends 47 percent of her or his waking life not paying attention to what they’re doing. And when they’re not paying attention to what they’re doing, they’re less happy. So that’s the first pillar of well-being: awareness.

Second pillar of well-being is something that we’ve already been talking quite extensively about. We call it connection, and it really is about the qualities that are essential for healthy social relationships; qualities like appreciation and gratitude and kindness and compassion. And the simple kind of appreciation exercise that I described earlier is one example. Another example, which takes me — I do it daily — it takes me maybe a minute or a minute-and-a-half at the most — is every day, in the morning, after I sit and meditate, I’ll take out my calendar. And I’ll look at everything I’m going to be doing that day, and I’ll reflect on the people that I’m going to be interacting with. And I spend just a few seconds bringing each person into my mind and heart and reflecting on how I can show up in a way that will be maximally beneficial, and appreciate who they are and what they’re doing. And that simple exercise has helped me enormously, to navigate days that are filled with Zoom calls.

Tippett: That is so refreshing, because I think — and it’s so familiar, is that moment of looking at my calendar, which I often find so oppressive. And, you know, I want to say also, I also appreciate that you’re putting an ecosystem of words around “connection.” You know, “connection” is a word we need. We can’t let go of the word “connection.” I mean, obviously, it’s a foundation of well-being and so many other things. But we need — we can’t rely on that word. And so I appreciate surrounding it with words like “appreciation” and “kindness” and “compassion” — not just talking about “connection.” I mean, we have lots of connection that’s not good for us, right? But this is a quality of connection.

Davidson: Yes, and I think that’s really so important. And one of the things about connection and the way that we are thinking about it, with healthy forms of connection, is that we can see the seeds of connection from very early on in life. And we think of qualities that are part of connection, like kindness, in the same way that scientists think about language — that they are part of our nature. And just as it is for language, these qualities require nurturing in order for them to flourish, in order for them to be expressed. And there have been these fascinating case studies of children raised in the wild, who do not develop normal language because they have not been exposed to a normal linguistic community. And in the same way, kindness is a quality that is important to nourish, for these seeds to really grow.

Tippett: We are rapidly racing towards the end of our time. I’m just looking at the clock. You know, the last time, Richie, you and I were together, it was in Orange County, California, in an old-fashioned, three-dimensional, in-the-flesh gathering with a bunch of wonderful educators. And they had proposed the topic — that we speak about and that they learn from you what you’re learning about love and kindness, as an aspect of education. And Vivek, I think that echoes what you said about, you know, the longings you are naming as a parent, for how do we define that robustly, and with well-being in mind?

I guess I kind of just want to throw that out there, that language of love and kindness. Are there ways that are also backed with intelligence, and even science, that you can imagine us thinking about love and kindness and life together? And I think that love — not as a feeling, but as it actually functions in life, as much more often actions, right, daily, quiet actions, sometimes happen in spite of how one feels at the moment; that they’re commitments that we make to each other.

Murthy: I do think that in many ways the pandemic has made me more optimistic about the future, about where we’re all headed, because sometimes you have to take things apart in order to put them back together in a better way, in a stronger way. And I think at the heart of this is, in fact, what you spoke of, Krista; is love.

I’m reminded, as you speak, about those days when I — that day in particular when I came home and, when I was surgeon general the first time around, in the Obama administration, and I encountered my wife, who was sitting in the living room. And she just looked really happy. She had this big smile on her face. And I said, Well, what’s going on? And she showed me this pregnancy test indicator that was positive. She said, We’re going to be parents. And it was going to be our first child, and we were just over the moon. We were so thrilled.

And of course, then my mind immediately raced to all the things I was anxious about — do we need to move to a bigger house? Do we need to do this, that, etc.? But the thing I actually found myself most preoccupied with in the days that followed was the question of what kind of world we were bringing our child into, recognizing this was a time, in 2016, where there was a great deal of strife, there was a great deal of polarization — that hasn’t gone away, obviously, since then, but we were seeing so much of the negativity and fear in the world just splashed across the newspapers and the headlines on TV.

The question I have found myself asking again and again is, what can we do in our lives, through the decisions we make, choices we make, about how to tip the scales in the world away from fear and toward love? How can we do that through how we treat other people, through what we say, through the issues we choose to speak up on in the public square, through the jobs we take and the purpose we seek to fulfill? How can we tilt the world toward love and away from fear?

And ever since then, Krista — we’ve been blessed with another child, and that has only, the opportunity to have another child I think has only strengthened, I think, in us just the conviction that it’s our responsibility to do all we can. And I have seen, I’ve been so grateful to see, in the years since then, that these qualities that we are talking about today — compassion, kindness — all fundamentally derivatives of love — that these are healing. And I say that as somebody who has had the privilege of prescribing many medicines over time. There’s nothing more powerful that heals than love.

And that starts with what we teach our children, with what we choose to practice, like in our day-to-day life, and with fundamentally recognizing that public health is about more than policy and about structure. It’s about culture, values, and identity. And if we anchor that culture, our identity, our values in love, I think that will guide us to the place where we need to go, and truly be healthy and happy, which is, I believe, what we all want.

Davidson: I think it is in the simple activities of our daily life that we can bring these qualities of love and kindness and make this decision that Vivek has so beautifully and starkly put. This is a choice between love and fear, and love is what is consistent with our nature. And it doesn’t take much to get it going. One of the amazing things that we’ve learned during the pandemic — we did this study with public school teachers where we were offering some simple practices to nurture their well-being during the pandemic. And one of the teachers said to us that this set of practices helped to remind them of why they chose to be teachers in the first place, and their love of children and love of learning, and that they tapped into that for the first time during the pandemic, and it just unleashed this energy and this resilience and vitality that enabled them to keep going.

This is something that is accessible to all of us. And so I’d like to invite all of us to be part of this change; to make a commitment — how can we bring love and its derivatives into our daily life? This is, I think, the aspiration that we all have, coming out of this pandemic.

Tippett: Thank you. I’m so grateful to be part of this and for the work that you and your colleagues all do in the world.

Murthy: Thank you, Krista. And thank you, Richie, for bringing us together. Grateful for both of you.

Davidson: Thank you.

[music: “Vittoro” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: Richard Davidson is the William James and Vilas Research Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He founded and directs the Center for Healthy Minds there, and was the founding director of the Waisman Brain Imaging Lab. He is also the founder and “chief visionary” for Healthy Minds Innovations, a nonprofit that translates laboratory science into real world tools.

Dr. Vivek Murthy is the 21st United States Surgeon General, commanding a service of more than 6600 public health officers. He also served this role from 2014 to 2017.

[music: “Vittoro” by Blue Dot Sessions]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt, Gautam Srikishan, Lillie Benowitz, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Matt Martinez, and Amy Chatelaine.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear, singing at the end of our show, is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org;

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org;

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives;

The Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education;

And the Ford Foundation, working to strengthen democratic values, reduce poverty and injustice, promote international cooperation, and advance human achievement worldwide.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.