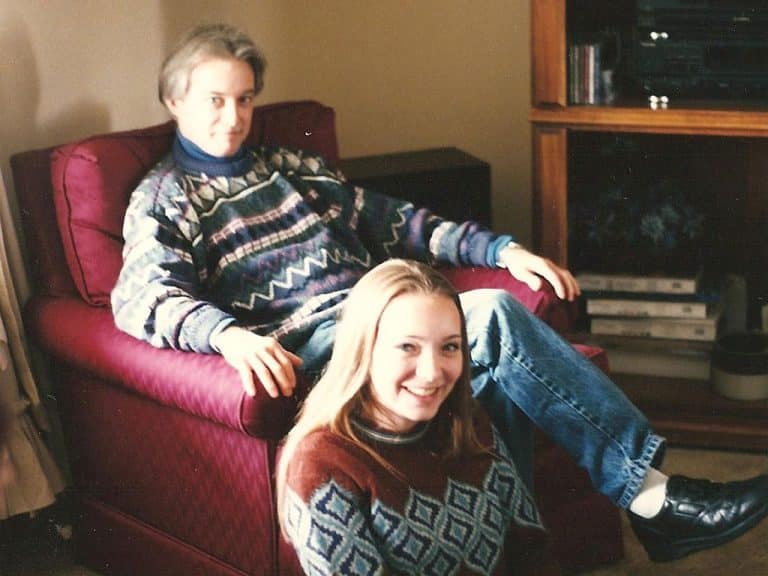

Courtney Seiberling sits with her father. Image by Courtney Seiberling, © All Rights Reserved.

When Things End, There’s a Magic To It All

When I turned eight, my parents took me to the circus. There was more color than in real life, and the tent was twice as tall as the ceilings at the grocery store. Trapeze artists swung from ropes and twisted into contortions more obscure than my dog, but what really thrilled me most was the unicorn.

The unicorn’s entrance had been grand. Invisible flutes and accordions played over the speakers, and then the ringmaster commanded the audience’s attention through a giant microphone.

“Ladies and gentlemen, children of all ages, are you ready for some mysticism? Folks, we have a very special creature to behold this evening. All the way from the silver sands of Persia… the rare… the numinous… Lancelot, the Living Unicorn!”

Ambient music wafted through the room as a fluffy-maned unicorn clomped into the spotlight. His long horn swirled around itself like a twisted lollipop, making me believe that anything could happen, just like my parents had said when I told them I wanted to be a snake charmer or the first female president.

“I am looking for one lass or maiden to place their hands on this magical creature,” said the ringmaster as he searched the crowd for a volunteer.

Could it be? I looked at each of my parents for permission to raise my hand.

“Go ahead,” my mother encouraged as my father nudged my arm up. Hundreds of us reached for recognition as a drumroll rounded the room and when the cymbals crashed, the ringmaster was pointing at me. My father lifted me from under my armpits and ushered me down the bleacher steps until I was standing on the hay-crusted floor, holding the hand of the man who had chosen me.

“What is your name, young maiden, and where are you from?” the ringmaster asked with an affected voice and then placed the microphone below my chin. I couldn’t see anyone under the heat of the yellow lights.

“Courtney,” I said with conviction, “from Lancaster.” My eyes adjusted, and I found my father to make sure it was okay to answer him. This wasn’t stranger danger. This was destiny. I was going to pet a unicorn.

The ringmaster’s assistant knelt down to tell me how to approach Lancelot, her blue lashes fluttering between directives. As I walked towards the magical beast, I knew I was looking into eyes that knew all the answers of the universe. I placed the back of my wrist upon Lancelot’s neck and stroked downward with my fingers. The hair was less coarse than it looked, and his muscles were more curved and firm than I could see from my seat.

White dust began flaking off onto my hand, and I wondered what kind of powers I might absorb as the music started up again. The sparkly assistant took my hand, and we began a procession behind the unicorn, circling the arena that had a sweet-hooved aroma. I searched the crowd for my mom’s purple sweater and found her and my dad in it. I could tell they were proud.

After the parade, the ringmaster handed me a certificate, and the audience clapped. I waved a final wave, and my dad came down to the rim of the audience to snap a photograph.

The following week for show-and-tell, I brought in the certificate. I waited to go last, until all my classmates had shared their new toys or lost teeth. When it was my turn, I walked to the front of the classroom wearing my pink Barnum & Bailey t-shirt and prepared for the rounds of applause that would surely follow. I framed myself between the chalkboard and hamster cage, delicately holding the ivory parchment paper so I wouldn’t wrinkle it. My classmates quieted and looked to me. I was serious, and they knew I had something special to share.

“Okay, Courtney, go ahead,” Mrs. Hughes prompted. She was old and curt and probably had no business being an elementary school teacher. Allowing a delicious pause to permeate until it created the dramatic effect desired, I announced loud and clear: “I got chosen to pet a unicorn.”

I held up the certificate and pointed to my circus shirt just like I’d practiced in the mirror on the coat closet at home. The boys seemed indifferent to what I’d just said, but a few of the girls gasped, and then one shot her hand up in the air like a firework, waiting to be called upon. But before I could, our teacher interrupted.

“Oh honey, that wasn’t a unicorn,” Mrs. Hughes sneered. “That was just a goat with a horn glued on its head.”

My heart plummeted to my stomach like a failed paper plane. I was mortified. Confused. It couldn’t be, I thought. I’d felt Lancelot with my own hands. Seen his horn with my eyes! I took a good look at our teacher’s face and contemplated what she just said. Bonding a horn to something that already existed did seem more probable than capturing a legendary creature. Standing up in front of all my classmates, I realized I’d been duped.

The bell rang, and I stuffed the certificate into my backpack. I ran home and changed my shirt, swearing I’d never wear it again, and then cried and beat my fists into the soggy bed. I buried the certificate in a drawer and left it there for all of eternity.

***

I stopped believing in Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy by the time I was nine. Even the Easter Bunny seemed like an unreasonable contender. I tried reinvesting in the possibility of these annual visitors for a few rounds of holiday seasons, but the image of a goat with a horn glued on its head was branded on the back of my brain. My mom attempted to keep up the façade, staging our living room on Christmas morning with little gold bells that she suspected must have fallen from Santa’s coat when he slid down the chimney, and I went along with it for the sake of my little brother. He was still a believer, but I knew that it was a big, fat lie and was confused why our parents were buying into all these conspiracies. But it was okay, because there would still be presents whether Santa brought them or not.

By ten, I realized that my parents didn’t know everything and that my best friend made things up when I asked her questions like Why is the sky blue? Even Miss Cleo, host of The Psychic Readers Network, seemed phony, and the news was starting to broadcast words I understood. Desert Storm was a war and people were dying. Even though I knew we were safe in our house, the sandy terrain and tanks on TV were becoming more real to me than a land where unicorns lived. A cloud of realism was now always lurking over me just like that pile of dust that always follows Pig-Pen.

And yet, a part of me couldn’t give up on the idea of magic. Maybe flying reindeer and tooth-seeking fairies were a bit far-fetched, but if magicians could make magic themselves, couldn’t I? I found it was possible on the stage. The summer after my 16th birthday, I spent a week at Show Choir Camp singing and dancing my way into this other world. The week culminated in a performance, but my parents didn’t come because my dad was sick. I was mad. We were doing a medley from Disney’s Hercules, and I had the solo. I went through the motions and smiled, shaking my hands in the same pattern as everyone else, but it didn’t feel the same. I was needy for approval, for applause from people who would remember what I’d done.

When I got home from camp, my little brother and I were called into the dining room. My parents sat stoic and serious at the table as the curtains flapped forward like pirate sails, the window-boxed air-conditioner blasting my long, Sun-In’d hair around. The direct air made my shoulders cold, but I took a seat next to my mother and kept quiet. My towheaded brother was distracted and wanted to go back outside to play but threw himself up on a chair anyway. It wasn’t dinner time and neither of us had done anything wrong, so we just waited to see what was going to happen next.

My father began a monologue, “I love you two,” he said. “Your mom and I love you more than anything.” There was a strange formality in his tone as if he was giving a presentation he’d rehearsed. A housefly bantered around the room.

“I have something difficult to share,” he continued. “But I promise that it’s all going to be okay.”

My mother sat in silence beside him. Her hand was on the table that still had glitter in the center seam from an art project I’d made. She was flicking her nails. My mom was usually the one to lead family conversations, the discussions about vacations or how my brother was getting to a game, but this was about something else. As my father went on, she continued to say nothing like a first lady at a president’s side.

“I’m sick and have to have a bone marrow transplant,” my father explained. “But your uncle is a match.”

My little brother scrunched up his nose, trying to make sense of it. I’d never seen his face so adult-like and knowing. My mother kept looking down, staring at a groove in the table, and I thought it was strange that she still hadn’t said anything.

“I love you guys,” my father said again. “It’s all going to be okay.” His voice was softer now, more like the one I recognized, but I stopped hearing it and watched his hair feather in the fog of feelings that was thick between us all. The t-shirt he wore was the same color as his earth-gray eyes and had the logo of a band that we had just seen in concert a month ago. We’d sang and danced in the stadium seats, and nothing had been wrong like it was now. My brother was back to looking like a kid again and was showing his impatience, his little legs kicking all around underneath the table. He wanted to go back outside to play.

My dad reiterated for a final time that it would all work out. He’d never lied about anything before, so why would he lie about something like this now? Walking around the table in a somber round of duck, duck, goose, he sealed his promise with a kiss on the top of each of our heads. I think we all felt chosen as the goose but didn’t know how to chase him down a road he had to run alone.

We were dismissed, and my dad disappeared upstairs. My mom went into the kitchen to start dinner. She took a pot from the cupboard and turned on the faucet, and I swear she was crying, but I wasn’t sure because all I could see was her back breathing irregularly. She was looking out the window above the sink, watching my brother, who was already back outside kicking his soccer ball against the garage door.

I didn’t know what to do, so I called my friend Moriah and asked her to drive me to the mall. I didn’t say anything about my dad or what he’d just told us, and she said she couldn’t drive me because her family was going to dinner, so we said we’d go tomorrow and hung up. I fanned through the stack of mail and saw that the fall fashion issue of Seventeen had come, so I tucked the magazine under my arm and went into the living room where my dad was watching VH1’s Behind the Music. I sat down beside him on the couch and leafed through the sleek pages, trying to decide what I was going to wear on the first day back to school.

***

My dad was hospitalized two months later. He’d caught a cold, and his weak immune system wasn’t fighting it. The temporary bed they put him in was too large for his shrinking body, and a creamy, yellow gunk had begun to coat the whites of his eyes. I wrote a letter on my angel stationery and brought it with me to the hospital to read, scared I wouldn’t know what to say to him and knowing how important whatever I did should be. I don’t remember what that letter said now, only that I’d wanted the words to do something more than end. I’ve always wanted things to be different from how they are.

On August 12, my dad was gone before he left his body, and then he was gone completely. My mom was alone at the hospital. I have no idea how long she waited before she drove home, but when I heard her keys in the door, I knew something was wrong. Her face said the unsayable, and we all stopped breathing for a moment until our bodies remembered to breathe themselves. It was the first time I thought of magic being in our breath, in something seemingly so mundane. Breath had been the thing that had given air to my father’s voice and pigment to his skin until it didn’t anymore.

I wonder what I was doing the moment my dad had stopped breathing. Ordering Chinese food? Telling my brother to turn the volume down on his video game as he advanced to the next level? Did my dad advance to the next level? I miss Mrs. Hughes’s unshakable way of defining things for what they were, but I don’t know if any of us can really explain death. It shakes us. There is very little understanding when things end.

***

We put my father in the ground on the top of a hill by a tree overlooking other hills and trees. It’s a special place with a sky twenty times as high as that circus tent, and I’d visit his grave whenever I needed to feel him. By November, the dirt had hardened. Snow was starting to fall outside the windows of my high school, and people had stopped asking me how I was. This is the unfair part of mourning. Of course, the death itself is unfair, but just as I was beginning to grieve, everyone else was back to talking about normal things. There were no longer fresh-cut flowers delivered or ready-made casseroles in the fridge, just a lot of empty space that my father used to fill.

After high school, I went to college and shared stories about my dad with anyone who would listen. Memories kept him alive, and I wasn’t ready to forget him. I wore his concert t-shirts and tacked photos he’d taken on the cork board in my dorm room, pinning the one of me and the unicorn in the center. In the photo, I’m wearing a yellow shirt and green polyester shorts, grinning ear to ear with a missing tooth; Lancelot is to my right, and the assistant’s thin, shiny legs are in the background. I’d look at that picture as though it was a portal that could take me back to what it had been like not to have lost so much, but all it ever did was remind me of what I had.

For months, I missed parties and football games to run a museum out of my dorm room, granting admission to anyone who would sit on my bottom bunk and flip through my high school yearbooks with me. If I could prove who I’d been, I wouldn’t have to figure out who I now was. But like those black and white photos, I’d lost the color of my life.

I needed to keep going, to start opening to what was happening around me. I brought my yearbooks home on a break and went to parties when I returned. I auditioned for plays and drank beer after rehearsals and talked about Tennessee Williams and bands. I stayed up late and woke up early to run and feel the cold air punch my lungs and remind me how wonderful it was to be alive.

As I remembered, something started to happen. My dad came to me. Instead of in the stiff earth, he appeared in a Neil Young song on the radio. Rather than beneath a glossed stone, he showed up in the way I preferred my coffee. Today, he’s often a nudge of encouragement for everything that is possible or a reminder of all that isn’t. Things end. But something else always begins. There’s a magic to it all.