A lady walks the street of Shinjuku. Image by Takeshi Garcia/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)..

Letters to the Living No. 1: Can You See the Infinite?

“Precious those little hidden lakelets of knowledge in the high mountains, far removed from the vulgar eye, only visited by the soaring birds of love.”

— George Eliot

When I was a kid growing up in central Florida, my mother had a thick tome of George Eliot’s letters that my father had given her as a “just because” gift. I still have it, sitting on my childhood dresser. It has a mauve dust-jacket with a portrait of Eliot (the pen name of Mary Ann Evans) as a middle-aged woman.

As a four- or five-year-old girl, I remember gazing at her portrait and thinking that here was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. There was a deep and piercing kindness about her face that drew me in.

I was shocked, years later, when I heard a commentator refer to George Eliot as a “plain” and “homely” woman, though (by way of consolation) she did have a glittering intellect. Curious, I dug out an old postcard with Eliot’s photograph on it. Painters tend to soften features, and sure enough, the photo shows that she was not, conventionally-speaking, beautiful. In fact, by modern standards, she would be considered quite unusual-looking.

And yet, I still think she’s one of the most beautiful woman I’ve ever truly seen. When a face is enlivened by spirit, knowledge, and compassion for others, it is only the dust in our own eyes that prevents us from seeing its loveliness.

This dust-in-our-eyes can take the form of self-criticism, unhappiness, and our constant comparison with others that breeds anxiety and fear. In fact, the Indian philosopher J. Krishnamurti spoke about comparison as one of the roots of fear:

“But if I am all the time comparing with you who are bright, nice looking, then I am running away from myself, trying to imitate, trying to conform to the pattern you have set…See the danger of comparison, which maintains fear.”

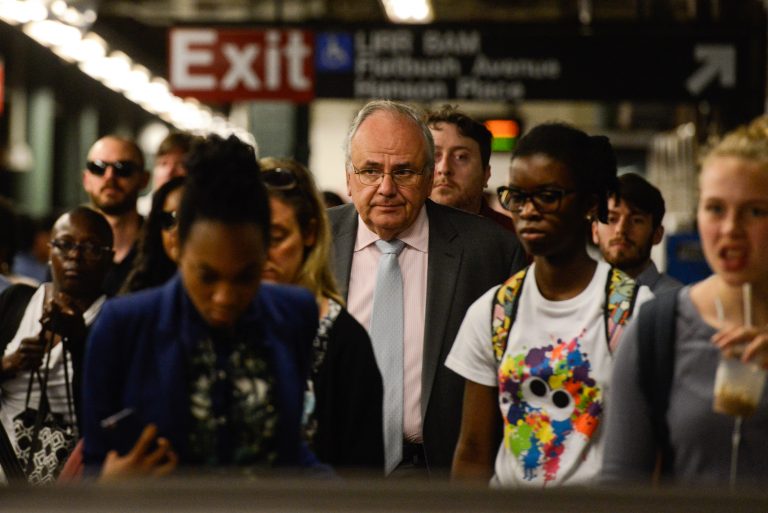

I think about my own habitual comparisons, especially — as a young woman — with regard to my appearance. If you’re a girl or woman, you’ve experienced “the look.” You’re walking down the street, minding your own business, listening to music or chatting with a friend and a woman approaches from the opposite direction. In a flash, she sweeps you up and down with her eyes, sizing you up.

I used to think, whenever I got the look, that it reflected on how poorly I match society’s standards of beauty. Only years later did I realize that women (and men) dispense the look only when they are worried about their own appearance. Criticism and comparison with others mask our own fears, hurts, and deep misperceptions about ourselves. I assure you, people who give others the look are constantly giving themselves a harsher, more damaging version of it.

There’s a reason why we give people looks and not “sights.” Seeing is of a different nature than looking. An artist friend recently described art itself as “a capacity to see.” I’ve always been fascinated by the connection between sight, integrity, and love. Martin Buber delves into this connection when he describes the “I-Thou” relationship:

“Measure and comparison have fled. It is up to you how much of the immeasurable becomes reality for you. … It does not stand outside you, it touches your ground; and if you say ‘soul of my soul’ you have not said too much.”

Fear is gone. The dust is washed from our eyes.

J. David Velleman, a philosophy professor at NYU, makes a strong argument for the relationship between this capacity to see and love itself:

“Grasping someone’s personhood intellectually may be enough to make us respect him, but unless we actually see a person in the human being confronting us, we won’t be moved to love.”

Encountering the face or voice of a person who can see changes us. It is not like light ricocheting off a shiny surface. Rather, we absorb the beauty that they see in others. In this way, the beauty of being beheld becomes part of us.

Perhaps this is what I sensed as a child, staring at George Eliot’s portrait. This was a woman who actually did see people. More powerful yet, she was able to translate those in-sights into language that helped others see more clearly and lovingly too.

So next time someone gives you the look, try this: instead of responding in kind, exercise your capacity to see. You may be surprised what beauty mirrors back.

Because, hand in hand with this capacity to see is the capacity to be seen. How many of us are ready to step into the gaze of someone — including ourselves — who sees us as we really are?

As Ms. Mary Ann Evans wrote in her letters:

“Though you have beheld many more beauties than I, I do believe that would be quite new to you.”