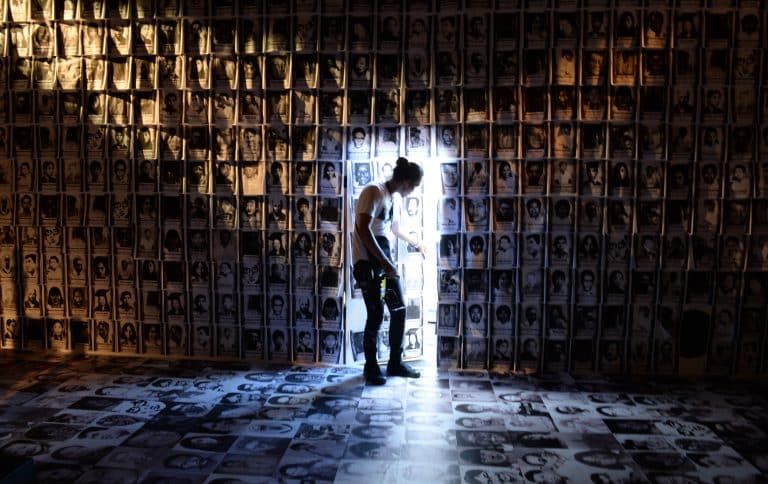

A man stands among photos taken of human rights victims during martial law, displayed at an experiential museum inside a military camp in Manila on February 24, 2016. Image by Ted Aljibe/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

The Shape of Totalitarianism and the Meaning of Exile: Three Lessons from Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt was, in her own words, an “illegal immigrant.” She had never been under any illusions about the capacities of the Nazi regime, but when she was caught doing clandestine work for a Zionist organization in 1933, she knew she had no to choice but to leave. In the late spring, she crossed the German-Czech border through a safe house. “Guests” would arrive at the front door, in Germany, take dinner, and then depart through the back door, which happened to be in Czechoslovakia. Arendt would spend the next 18 years as a stateless person.

Arendt knew she was an “exception” refugee, one of the fortunate. Others were unwanted, superfluous. Something shifted in the way vulnerable strangers were treated in the West in the first part of the twentieth century. In 1944 Arendt wrote:

“Everywhere the word ‘exile’, which once had an undertone of almost sacred awe, now provokes the idea of something simultaneously suspicious and unfortunate.”

Today, we live under the shadow of that change. For millions of the unfortunate that means misery and uncertainty; it means untimely and undignified deaths, chronic sickness, separated families, violence, and poverty; it means tirelessly struggling to persuade yourself and the world that you, your family, and your community still exist in the world. It means being detained in airports and being taken off planes. And while all this endless work is going on, others watch with baffled and outraged dismay as the barely-articulate forces of nationalist hate crash into the legal and political structures that were built to protect ourselves, and others, from the same barbarism that pushed Arendt’s generation onto the refugee rat runs and into the detention and death camps.

Arendt took many lessons from her own refugee history that we might benefit from thinking about today. Here are three of them.

First, when you have a “refugee” crisis what you also have is a political, existential, and moral crisis about what a country is and who its citizens are. The First World War “exploded” the community of European nations. The financial crash killed the prospects of millions. Civil and colonial wars, persecutions and pogroms followed. Then came the refugees; stateless, homeless, “the scum of the earth” in Arthur Koestler’s phrase, the “rightless” in Arendt’s. That refugee crisis revealed a horrible truth about human rights: they were only as good as the nation you happened to live in; that is, if you happened to live somewhere in the grip of nationalist racism, not very good at all. This is was particularly bad news when other nations were also scrambling to protect their own self interest. “The world,” Arendt observed, “found nothing sacred in the abstract nakedness of being human.” Refugees, then as now, were everybody’s human rights crisis.

Second, if you want a politics committed to democracy and human rights, you must be historically and actively vigilant. Totalitarian regimes are easy to spot; they exist in history books and far-away places. It’s more difficult to recognize the totalitarian elements in one’s own place and time. In the 1950s, amid the “make America more American” campaign, the McCarran-Walters Act proposed a revised immigration model. This was a Cold-War piece of legislation designed, from one perspective, to improve foreign policy by appearing to change the race bias of the quota system whilst actually battening down the hatches in the name of national security and keeping America safe from communists and other undesirables. Truman thought it discriminatory and vetoed it. He was overruled by Congress.

Arendt was appalled and frightened by this turn of events in the adopted country she admired, if not uncritically, for its democratic processes. America would not be more American by keeping or throwing certain people out, based on their race or their beliefs, she pointed out, it would be committing a crime against humanity:

“As long as mankind is nationally and territorially organized in states, a stateless person is not simply expelled from one country, native or adopted, but from all countries … which means he is actually expelled from humanity.”

How you police your borders is not just about strangers. In fact, a lot of the time it’s hardly about refugees or migrants at all. It’s about citizenship. Start on that category, Arendt taught, and nobody is safe:

“It seems absurd, but the fact is that, under the political circumstances of the century, Constitutional Amendment may be needed to assure Americans that they cannot be deprived of their citizenship, no matter what they do.”

Third, beware of making hasty historical comparisons. One thing her own history had taught Arendt was that the impossible can become possible with mind-defying brutality and alacrity. Trying to grasp the unprecedented through the precedented, she discovered, risked not understanding how a different number of elements have to be in place in order for atrocity to happen. The “punishing” of refugees for things they haven’t done doesn’t happen just because of racism, uncontrolled global expansion, imperialism, financial crises, and nasty nationalisms, it arises out of a particular constellation of all these things. To ascribe “obvious” causes, to say that this state of affairs is “easily explained,” is to is to normalize the politically and morally abhorrent.

Arendt’s experience of history as a refugee in the last century was not “just like” the experience of being a refugee today, nor is our contemporary fascism like the old fascism — if only because they are all part of the same history. The bitter events of the past months are the latest chapter of a refugee history that is in fact everybody’s history, and its latest challenge to our historical, moral, and political imagination.

This essay was originally published in Refugee History on January 30, 2017. It is reprinted here with permission.