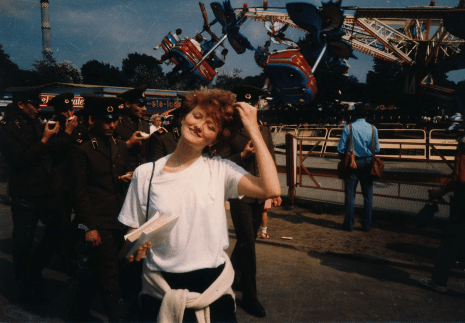

Krista Tippett in East Germany in the 1980s.

What the Berlin Wall and ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ Taught Me About Time

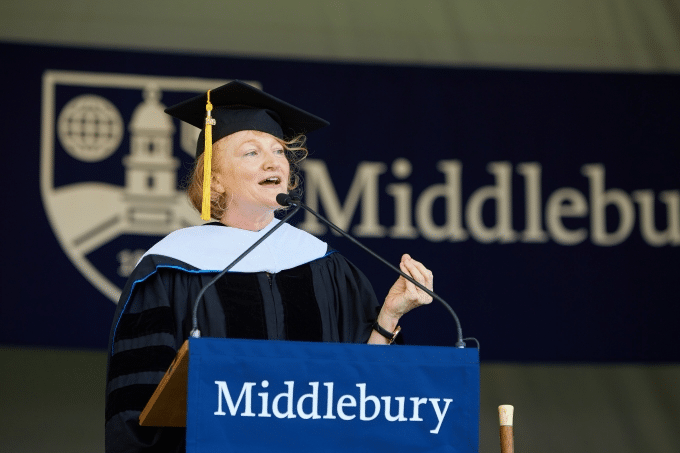

Author’s Note: I spent most of my 20s — most of the 1980s — in divided Germany. I landed first in Rostock on the Baltic as part of a bizarre exchange program and then spent a year in Bonn on a Fulbright after graduating college. I arrived in divided Berlin as the New York Times stringer in 1984 and spent four years there, in the end as Special Assistant to the U.S. ambassador, a nuclear arms negotiator. In those years, no one west or east could imagine that the Berlin Wall could disappear in our lifetime. On my 29th birthday, I learned as I stepped off an airplane in Oklahoma that the Wall had opened up. (None of my German friends has ever forgotten my birthday.) That vanished divided Berlin and its Cold War world feel increasingly resonant to me — invisibly formative in the lineage of the world we’re struggling to navigate now. It also holds me as I navigate the present with the memory there is in any moment more to reality than we can see and more change possible than we can begin to imagine. This story is part of a book I’m now writing on how we walked into this moment we inhabit, and how we can walk out of it.

Revolutions large and small don’t happen when the lid is on tight but when it has shifted just off-kilter. Things in fact may be getting a little better, or at least a little more honest. Behind the scenes, beneath the surface, below the radar, the ground has been shifting, a new vision fermenting. Now, despair, just slightly leavened by possibility, gives rise to irrepressible longing and hopeful abandon. The table is not laid; everyone is not ready for it. But hope has broken the surface, and what was long tolerated is suddenly intolerable. What happens next looks inevitable later, but in the moment it is unexpected and unpredictable. There are signs of shifting but from one angle the shifting appears contained and from the other it can’t move far or quickly enough.

At this kind of threshold, despair gives rise to longing and to hope — even if that hope sits unnamed and unsure of itself at the edge of the question: How could we have been living this way? This kind of question and this kind of hope — they are muscles.

The Berlin I inhabited still had a lid on tight. But in those middle years of the ’80s, it started to slip ever so slightly and imperceptibly at first. There was a new Soviet leader, Gorbachev, who changed nothing dramatic but somehow made a new reality possible against his intentions. Like our Pope Francis, he did not alter significant doctrines, but he shifted the spirit of things, and that had a way of shifting the nature of the possible. He changed small things that were really symbolic yet allowed long pent-up hopes to surface, to feel themselves. For example, Gorbachev was born with a large port-wine birthmark on his forehead. In Neues Deutschland (the official East German daily newspaper of the Communist Party), his birthmark was airbrushed out in pictures of him in the early days. Soviet leaders were meant to be flawless. One day in the middle of his new rule, the birthmark showed — and this, at the direction, it was whispered at dinner parties, of Gorbachev’s Politburo itself. That a Soviet leader was human and flawed was allowed to enter the imagination of the proletariat.

I remember, too, his first visit to East Berlin, where he did the extraordinary thing of bringing his lovely wife Raisa on his obligatory tour of factories, the supposed heart of the Workers’ State. Rather than give stuffy speeches and remain at a remove, they walked around and spoke with people. They shook hands. They asked questions and listened and smiled. The effect of this on the watching society was seismic. People cried, overcome. His humanity was unlocking theirs. It had nothing to do with politics and everything to do with politics.

In those years, there were longings and activities already happening across the Wall through Berlin — young peace activists on both sides finding each other and then a new generation of environmental consciousness. At that time, the fledging Green Party in the West was dismissed roundly by the political establishment. Today it is one of whole Germany’s major political and social forces. In those early hidden days of its force, one of its manifestations in Berlin was community formed across the Wall with young East Berliners. The air they breathed, after all, could not be split down the middle. This was a stake they had in common larger than politics and strategies, defying and transcending them.

As the old order started to waver, there was a fair amount of tragedy and terrible, costly, unnerving chaos. The borders in other East European countries began to loosen, and East Germans began to flock to these places with a desperate hope that they would find a way out there. Western embassies became places of refuge, over-full, desperate places not designed as refugee camps. There were people scaling fences to get in. People died. Still no one imagined that the Wall could come down. All that new flux beneath the surface had no place to go and no obvious course to success. Gorbachev, for all his smiles and the new words he’d brought into the public sphere — glasnost (transparency) and perestroika (reconstruction) — were a path of reform of the given order, not its dismantling.

Even on the day the Wall fell — November 9, 1989 — nothing that morning as people woke up presaged what would happen that night. The president of West Germany was traveling abroad. In East Berlin, a bumbling bureaucrat misspoke at a late evening press conference, saying that his country men and women would now be allowed to apply for passports. But what people heard was possibility. And what they followed, as en masse the population of the entire city stepped out of their apartments and began to walk towards the checkpoints of the Wall, was the final unraveling of fear. The Wall had never had a chance against this mass of humanity, but for 40 years, that mass of humanity had not felt its power.

Of all my years in divided Germany, the one conversation that remains most vivid and unnerving to me had to do with time. It comes back to me often these days of the world feeling upside down and inside out and going to hell, as they used to say, in a hand basket.

It was with a woman — let’s call her Erdmute — who was the office manager of a Western news bureau based in East Berlin. The street on which she worked is now one of the most glamorous boulevards of (undivided) Berlin, but in those days it looked like a grainy, black and white photograph compared to any street on the western side of the Wall through that city. Old bullet holes from World War II pockmarked the sides of apartment buildings that the Communist Party had never had the industry or will to repair. The air smelled of brown coal, cheap coffee, and yearning.

I was a journalist then and also, as it happened, dating the journalist who ran that bureau. I found Erdmute secretly reading a copy of the Handmaid’s Tale that I had left lying around the office. Margaret Atwood had actually lived in Berlin in the early ’80s as she wrote parts of her dystopian vision of a novel. While it has been taken up as prescient in our time, I experienced it as shot through with the idiosyncratic heaviness and airlessness of the now-vanished Communist half-country euphemistically named the German Democratic Republic, the GDR, for short. Its cynical, unnatural, strictly enforced ordering of society, childbearing, and love was dogmatically religious in spirit, if technically atheist.

The only thing that had disappointed me in the novel was its ending. We never learn what happened to the oppressed, brave characters we come to know and to cheer on for summoning hope and action in the face of the impossible. Instead, there is epilogue of a social scientific conference a century in the future. The period of our beloved character’s despair and drama has been given a name and is now something studied by scholars in hindsight as contained and undone.

Erdmute was beside herself with exhilaration over this ending. I had never seen her so animated. “To imagine that a hundred years from now,” she said — risking censure if the microphones we now know were everywhere in that apartment captured her glee — “the GDR will just be a thing of the past, like that!” I am ashamed of myself, and happy for her, when I report that I pitied her that afternoon. Such was the sense of totality and finality in that historical moment that I could not imagine the beyond of it, even in a century.

Three years is what it took, not a hundred. There is, at any given moment, much we do not see and more change possible than we can imagine. This is a truth about time’s capaciousness and the multitude of questions that dwell fiercely within it. Live into that.