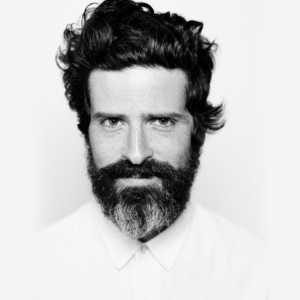

Devendra Banhart

‘When Things Fall Apart’

In this “spiritual book club” edition of the show, Krista and musician/artist Devendra Banhart read favorite passages and discuss When Things Fall Apart, a small book of great beauty by the Tibetan Buddhist teacher Pema Chödrön. It’s a work — like all works of spiritual genius — that speaks from the nooks and crannies and depths of a particular tradition, while conveying truths about humanity writ large. Their conversation speaks with special force to what it means to be alive and looking for meaning right now.

Image by Carlín Díaz/Carlín Díaz, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Devendra Banhart is a visual artist, musician, songwriter, and poet. His albums include Ma, Mala, What Will We Be, Smokey Rolls Down Thunder Canyon, and Cripple Crow, among others. His book of poetry is Weeping Gang Bliss Void Yab-Yum.

Transcript

Editor’s note: In 2018, the Buddhist Project Sunshine released reports on sexual violence and misconduct in the Shambhala Buddhist community going as far back as 1983. Pema Chödrön, who was part of the Shambhala community when those incidents occurred, was named in that report as having dismissed a claim of sexual assault from a woman. Pema Chödrön apologized shortly after that report was released, and in 2020 she announced her retirement as Shambhala teacher in a letter to the Shambhala community. Shambhala Publications, which publishes When Things Fall Apart as well as many other books by Pema Chödrön, is a 50 year old independent family-owned publisher of books and is not affiliated with any other organization or meditation center.

Krista Tippett, host: We live in unusual times and this is an unusual show — a kind of “spiritual book club” edition of On Being. When Things Fall Apart is a tiny volume by Pema Chödrön. She’s one of the greatest living teachers and writers in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. I’m not Buddhist, but I carry this book with me wherever I go. So do others on our team, including our executive producer Liliana Maria Percy Ruíz and our art director Erin Colasacco. So we set out to look for who else might be turning to this writing right now and quickly landed on the extraordinary musician and artist Devendra Banhart. He’s described his copy of When Things Fall Apart as a literary version of an “in case of emergency break glass” box. So from the emergency recording cave in my basement and his home studio in East Los Angeles, we read favorite passages to each other and reflect on what it is to be alive and looking for meaning right now.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Tippett: So maybe I’ll read a few of these parts from When Things Fall Apart. “Things falling apart is a kind of testing and also a kind of healing. We think that the point is to pass the test or to overcome the problem, but the truth is that things don’t really get solved. They come together and they fall apart. Then they come together again and fall apart again. It’s just like that. The healing comes from letting there be room for all of this to happen: room for grief, for relief, for misery, for joy.”

Devendra Banhart: Amen. That is just so now. It is just perfect. That passage is perfect. Perfect.

Tippett: I would just love to hear you read these two paragraphs.

Banhart: “The journey goes down, not up. It’s as if the mountain pointed toward the center of the earth instead of reaching into the sky. Instead of transcending the suffering of all creatures, we move toward the turbulence and doubt. We jump into it. We slide into it. We tiptoe into it … At our own pace, without speed or aggression, we move down and down and down. With us move millions of others, our companions in awakening from fear. At the bottom we discover water … Right down there in the thick of things, we discover the love that will not die.”

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

This is experimental. But I figure, since you’re a musician, you know about improvisation.

Banhart: [laughs] Oh, that’s funny.

Tippett: This is an interview version of improvisation, [laughs] both technically and content-wise.

Banhart: I love that, the idea of the improvisational conversation …

Tippett: Good.

Banhart: Every conversation is kind of improvisational. This is cool.

Tippett: [laughs] But the form here is different, too. Let’s say this is a new genre, because — well, first of all, we’re both speaking from isolation and reading this book that we’ve both read as life has fallen apart again and again, but in a very special, catastrophic way right now. And so the idea is that we would just talk to each other about what’s going on right now, but through — or to talk through the wisdom in Pema Chödrön’s When Things Fall Apart. And let’s just see what happens — how this works.

Thank you for sending the passages that you marked up, from your book.

Banhart: I hear that you have five copies of this book.

Tippett: I have at least three, and they’re not — I have two here, in my house, and I think I have — the one that you sent, that you took a picture of, I have at the office. That was kind of interesting, too, to look at what was marked up in the different copies, [laughs] which was probably a story of what was going on at that moment in my life when I read it last.

Banhart: I had the same feeling.

Tippett: Did you?

Banhart: I’ve got the 20th-anniversary edition, because when I first got this book, it was that — this is that book that you give to friends. But my version, it’s got all these bookmarks already in it.

Tippett: Do you remember when you first discovered this book, or how you discovered it?

Banhart: I don’t.

Tippett: Well, it’s interesting that that’s your answer, because this felt like a question I couldn’t not ask, but when I even asked it to myself, I have no memory of an origin story with this book coming into my life, because I feel like it’s accompanied me through, ever since. And I think, for me, also, I’m somebody who resisted the knowledge that things fall apart, or that — for a long time. And then, I think, when you finally accept that that is, actually, in the nature of reality again and again, you see it. And I think this book — I just always have it somewhere; it’s sometimes buried under a bunch of other books on my coffee table, but I carry it with me when I travel, just in case I need it. [laughs]

Banhart: It’s like, what kind of book is this? What do you tell somebody? What is this, if somebody says, “What is this book?” And the only answer I can think of is, applicable wisdom; utilitarian wisdom. [laughs] It really is that tool — OK, do I have my phone? Do I have a copy of When Things Fall Apart? — because I’m gonna need it through the day, because that thing — like you said, accepting that things fall apart — is something I’ve been resisting for my entire life, and it’s something that’s been happening every day.

Tippett: That’s right. [laughs]

Banhart: And so it’s not like once I realized — “Oh, that one time I realized that things do fall apart, and I need to accept that everything is ever-changing — that one time, and then I never had to deal with that ever again” — [laughs] it doesn’t work that way. And so it is something to have in your toolbelt.

Tippett: Well, I really just want to walk through the passages that you sent and talk about them. I did pull out my copy and thought, maybe, just as we start this is the very beginning — it’s about fear. “Intimacy with Fear” is the first chapter. And what could be more — I don’t even want to use the word “relevant,” because it’s too mild right now. We feel this fear in our bodies. “Embarking on the spiritual journey is like getting into a very small boat and setting out on the ocean to search for unknown lands. With wholehearted practice comes inspiration, but sooner or later we will also encounter fear. For all we know, when we get to the horizon, we are going to drop off the edge of the world. Like all explorers, we are drawn to discover what’s waiting out there without knowing yet if we have the courage to face it.”

This is on the next page. I’m just gonna read a few passages that … “Impermanence becomes vivid in the present moment; so do compassion and wonder and courage. And so does fear. In fact, anyone who stands on the edge of the unknown, fully in the present without reference point, experiences groundlessness. That’s when our understanding goes deeper, when we find that the present moment is a pretty vulnerable place and that this can be completely unnerving and completely tender at the same time.” [laughs]

Also, I think, this experience of the unknown right now, but that notion of the unnerving and the tender coexisting, I’ve always thought, is so beautiful.

Banhart: It’s like the opposite of the world we live in, meaning, this is truth. This is reality. This is how we actually always feel. This is what’s always going on, and you don’t hear about it in your day-to-day in the world. It’s not in the news, next to what’s happening, but it’s there. It’s bubbling under the surface, that uncertainty and that fear, and that thirst, too, to go on something like a journey of self-discovery, let’s say. But it’s so nice — because you don’t feel so alone. That’s kind of how I feel, reading the book, too. I go, Oh, gosh, I’m not alone.

Thanks for reading that, and I guess I kind of wanted to hear that 400 more times.

Tippett: And then reading it right now, is this extreme it’s an extreme kind of technicolor version of things falling apart, for everybody all at once, but it’s also, at the same time, a magnification of something that’s happening all the time. [laughs] We recognize this.

Banhart: Oh, absolutely, absolutely. I think that’s what — it can really strike a chord with anybody, and you can just categorize it as wisdom, because wisdom is so — it’s really not owned by anyone or any particular philosophy or system or religion — you don’t have to be a Buddhist to get into it and to feel it. That’s why it just can go under “wisdom.” It has this lightness to it, I suppose, even though it’s coming from an explicitly Buddhist place. But it feels very universal. It’s just completely what’s happening right now, and what’s happening right now is also what’s happening in us all the time.

Tippett: It’s this tradition being this lens through which a person who is living fully in their body, fully in the world going through life, then is able to articulate bedrock reality.

Banhart: Exactly.

Tippett: Well, do you want to read — you marked some passages in Chapter 7, “Hopelessness and Death.” [laughs]

Banhart: “Hopelessness and Death.” [laughs]

Tippett: Upbeat.

Banhart: Start on something light. Let’s start light and … [laughs] So let’s see. Page 37, Chapter 7, “Hopelessness and Death.” “If we’re willing to give up hope that insecurity and pain can be exterminated, then we can have the courage to relax with the groundlessness of our situation. This is the first step on the path … In Tibetan there’s an interesting word: ye tang che. The ye part means ‘totally, completely,’ and the rest of it means ‘exhausted.’ Altogether, ye tang che means ‘totally tired out.’ We might say ‘totally fed up.’ It describes an experience of complete hopelessness, of completely giving up hope. This is an important point. This is the beginning of the beginning. Without giving up hope — that there’s somewhere better to be, that there’s someone better to be — we will never relax with where we are or who we are.”

Right? Who would think, hopelessness, that’s the place to start? But it makes so much sense. [laughs]

Tippett: Well, it does; it’s funny, because — I don’t know, I hadn’t — the hopelessness piece — of course, I again have read it a hundred times, but you had marked this passage, and that language had slipped my mind. And it almost, actually, felt a little bit dangerous right now. [laughs]

Banhart: I get that, for sure.

Tippett: Even — oh, that Tibetan word — “totally, completely exhausted” — just what an image. And I also, when I read that, I think of, it’s hard to be alive right now and have a modicum of security and not be overwhelmed in thinking about so many people for whom the groundlessness is literal.

Banhart: Yeah. Oh, wow, yeah. I mean, 100 percent. I think I’ve never — I look forward to — I guess, here, on the West Coast, it’s 8:00 p.m. when we all start cheering and clapping for first responders and people that are working in the medical community, health care workers. So at 8:00 p.m. pots and pans start banging, and people start hollering and clapping, and somebody plays the national anthem on their electric guitar, super loud. It’s beautiful. It’s a really wild thing. And I grew up in Venezuela, in Caracas, Venezuela. And the last time I heard this was when they were trying to oust the president, Carlo Andrés Pérez, by Chávez, trying to oust the president, which is so weird, that people were on his — it’s a whole thing. But they were banging on the pots, yelling, “¡Son las diez, son las diez, que salga Carlos Andrés!” But it was like propaganda; people didn’t know what they were cheering for. It was just total manipulation, to get people to just — the madness of the crowd. And then this is the homegrown expression of gratitude and love, and the difference is just night and day, and I haven’t felt it since I was, I guess I must have been 11 years old, the last time I experienced that in Caracas.

But what’s amazing about this passage is that — when I say, again, so much about this book is “Oh, this feels really real; this feels really true, but I don’t really read about this in the news, throughout my day, throughout my regular life conditioning.” And it’s like you think, at the end of hope, That’s it. Oh, man, that’s it. I’ve given up. And so, it’s over. But actually, that’s when it really begins. And I think that is so — ironically, so inspiring and hopeful. But it’s really when you give up hope.

Tippett: [laughs] I know. It’s true.

[music: “Coulis Coulis” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today I’m with musician Devendra Banhart. We’re talking through our favorite passages of When Things Fall Apart, a classic, spiritual work by Pema Chödrön.

Tippett: You know, I use the word “hope” a lot, and I always use it, and I always say hope is muscular; hope is a muscle; hope is a choice, and hope isn’t like optimism, which is wishful thinking. So it challenges me, when Pema Chödrön uses this language of hopelessness. So then I was looking farther in the chapter, after you sent your passages, and — do you remember this? I think it’s on the next page. She says that the word in Tibetan for hope is “rewa.” The word for fear is “dokpa.” And there’s a word that is used, which combines hope and fear. And she says, “Hope and fear is a feeling with two sides. As long as there’s one, there’s always the other … In the world of hope and fear, we always have to change the channel, change the temperature, change the music, because something is getting uneasy, something is getting restless, something is beginning to hurt, … we keep looking for alternatives.” This is the place she says, “You could even put ‘Abandon hope’ on your refrigerator door instead of more conventional aspirations like ‘Every day in every way I’m getting better and better.’” [laughs]

Banhart: Ugh, I love that. I love that.

You know, I have a tattoo gun, and I think I just found my next tattoo: “Abandon hope.” I’ve never wanted to get a face tattoo, but I’m gonna consider it. Just wow, first thing I want to see in the morning. It’s great. It’s freeing, because it’s — ugh, I love that. I love that.

Tippett: Right. But just explain why it’s freeing, because every time I start explaining it to myself here, I feel like it doesn’t make sense.

Banhart: Well, I will explain it by reading another passage from, actually, the previous page. So this is the passage, and this is why I think it explains why it’s so freeing to hear “Abandon hope.” “To think that we can finally get it all together is unrealistic. To seek for some lasting security is futile. To undo our very ancient and very stuck habitual patterns of mind requires that we begin to turn around some of our most basic assumptions. Believing in a solid, separate self, continuing to seek pleasure and avoid pain, thinking that someone out there is to blame for our pain — one has to get totally fed up with these ways of thinking. One has to give up hope that this way of thinking will bring us satisfaction. Suffering begins to dissolve when we can question the belief or the hope that there’s anywhere to hide.”

Tippett: That does it.

Banhart: Yeah, that does it. [laughs] I really, though, think that there’s something very cool about what you said — that hope is a muscle, though.

Tippett: Well, I like to think that what this gets at a bit is the inadequacy of words, so that that hope is not — that that contains a meaning that is different from this hope/fear, this fear/hope.

Banhart: Exactly. We should clarify that we’re not saying that hope is bad and that we’re anti-hope. We’re not anti-hope. [laughs]

Tippett: No.

Banhart: No, but it’s more the reality of effacing this delusional hope that’s based on escaping suffering or just making everything good or running from something that feels bad, as opposed to — that line, “Suffering begins to dissolve when we can question the belief or the hope that there’s anywhere to hide” — that’s the thing. We’re stuck together. We’re in this together. There’s nowhere to hide. There’s a billion distractions, and so much of our entire life is spent in those distractions; and those are very subjective things, whatever our distraction is — I’ve got a bazillion katrillion. But the hope that suffering will go away if I don’t look at it, that’s the wrong kind of hope. That’s the hope we’re not so into. [laughs]

Tippett: Right. Well, she also talks about that hope we get addicted to.

Banhart: Oh, sure, right. “Someday” and “If only” — those words that are the worst words in the world. [laughs] “I’m gonna do — someday.” “Someday” will always keep us from doing the thing, and then “If only” will always keep us from doing the thing. So hope and those kinds of — and this imagined, projected future, that’s the wrong kind of hope, too. But hope as a muscle is so beautiful, like I’m gonna work on that, on hope. So it’s — how about this. It’s kind of like what are our real, actual superpowers? Human superpowers are patience — I’m gonna work on this superpower called patience. I’m gonna work on this superpower called kindness. I’m gonna work on a superpower called gratitude — because if I’ve got those things, if I really work on that, I can kind of maneuver through this world with these superpowers, you know?

Tippett: I love that. And so, when I think of hope that way — and I think it’s true of everything you’ve just said, the other superpowers — they work with reality. I’m not interested in something that works with ideals, really, or again, wishes. But gratitude that is based in reality, and reality as it is and not as we wish it to be, patience and hope and love, those are hard, robust — you’re right. They’re superpowers.

Banhart: Exactly; as you said, though, it’s not a wishing thing. I have hope that I can deal with this badness that is definitely here, [laughs] with patience, with kindness, and find something to be grateful for from it. I have no faith — I have zero, zilch, zero faith in today being a good day. Today will not be a good day.

Tippett: [laughs] Right, right.

Banhart: But I can try to do good today. Today, I’m gonna do a good thing. I’m gonna try to do good. But today is not gonna be a good day. [laughs]

Tippett: And if it is, it will surprise you and be a pleasant thing, [laughs] a pleasant surprise.

[music: “Waterbourne” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Devendra Banhart. And by the way, there’s a beautiful thing happening on our Instagram — Poetry Unbound and Friends — including former On Being guests reading and reflecting on poems that are accompanying them now – including Ocean Vuong, Jericho Brown, and Maria Popova. You can watch all these short, nourishing videos at On Being on Instagram.

[music: “Waterbourne” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today with a kind of “spiritual book club” edition. I’m with Devendra Banhart, who is Venezuelan American, a Buddhist practitioner, and a multiply-talented musician and artist. We’re talking about When Things Fall Apart, a small work of great beauty by the Tibetan Buddhist teacher Pema Chödrön. It’s a work, like all works of spiritual genius, that speaks from the nooks and crannies and depths of a particular tradition, while conveying truths about humanity writ large.

I have learned much from the psychological acuity of Buddhism, which comes up in this conversation with Devendra about living with things falling apart right now. For example, there’s a practice called tonglen, receiving the pain of the world on an in-breath and sending out what you wish for the world on an out-breath. Or there’s the notion of maras, which translates to “demons,” or “obstacles” to being meaningfully present to experiences and present to our own capacity to meet them.

Tippett: So you also marked some passages in another delightfully titled chapter, “Nonaggression and the Four Maras.” Pema Chödrön, someplace, this is how she summarized the four maras. And she said — of course, I’ve always known this but never put words around it — so one mara is seeking pleasure. One is trying to be who we think we are. [laughs] Third, how we use our emotions to keep ourselves dumb or asleep. And the fourth was fear of death, by which she doesn’t just mean the big death, which is one form of death, but all the many small deaths that happen in the course of days and weeks and a life.

Do you want to read some of what you circled?

Banhart: “The teachings tell us that obstacles occur at the outer level and at the inner level. In this context, the outer level is the sense that something or somebody has harmed us, interfering with the harmony and peace we thought was ours. Some rascal has ruined it all. This particular sense of obstacle occurs in relationships and in many other situations; we feel disappointed, harmed, confused, and attacked in a variety of ways. People have felt this way from the beginning of time.

“As for the inner level of obstacle, perhaps nothing ever really attacks us except our own confusion. Perhaps there is no solid obstacle except our own need to protect ourselves from being touched. Maybe the only enemy is that we don’t like the way reality is now and therefore wish it would go away fast.”

Talk about not liking the way reality is now. Now. [laughs] You know? This is like a huge sledgehammer of “now” — [laughs] global “now.”

Tippett: And I also have to say, these passages are the ones — they feel so true, for me. Each and every one of us has to work out who we are and how we are in this moment, with a particular intensity. And then I also feel like there are so many people who are literally — where these obstacles are existential.

I wondered if, also — your mother was Venezuelan; you weren’t born in Venezuela, but you went back there. And that is also a place that has had a lot of dire, kind of apocalyptic realities in recent years. And I wonder how you read these things — how you’ve read that with that context, which to me feels resonant with now, what every country, every community is experiencing on some level, the severity.

Banhart: Well, I feel like that passage deals with the inner and the outer obstacle, and the outer obstacle is just unavoidable. It’s just unavoidable. And it just grows in magnification, and I think Venezuela is a good example of that magnification that everyone’s feeling now. But before this pandemic, there was — think of Australia. There were these massive fires. Australia was on fire. And that was a real, concentrated, outer obstacle. And Venezuela — Venezuela, people have mass starvation and just the entire country is being held hostage, basically, by the military and a dictator. This is insane. And this is real, concentrated suffering. And then Tibet, mass torture in Tibet, and so these are really concentrated obstacles, and it doesn’t seem like those things ever go away. And, for me practicing Buddhism is kind of like preparing for a pandemic, [laughs] only in that it’s like a daily “Oh, bear witness to the suffering of this world. Bear witness to the suffering that your emotions are causing you. Sit with it. Learn to sit with it.”

And then there’s the inner obstacles, and I think that’s the beauty of — and the usefulness, so much. There’s so many reasons why this book is useful. But one of them is that you can turn to it to be taught how to deal with the things you can deal with. And those outer obstacles will never really stop coming. But the inner ones, you can learn how to dance with those. And I think that’s so helpful. But it’s a compounded suffering now, thanks to this, of course.

Tippett: And the practice of tonglen, which Pema Chödrön also writes about, especially in this chapter, “The Love That Will Not Die” — I’ve read that that’s also something you practice on a daily basis.

Banhart: Yes. Tonglen — taking and sending — tonglen is really helpful. I don’t know if it helps anybody but me, though. It’s pretty selfish, [laughs] actually. But it’s like, how can I deal with reading the news, in a way. So it’s like headline after headline of horror, and so how do I deal with it?

And so you treat reading the news each day like, OK, this is a way of dealing with so much horror in the news: I’m bearing witness to it, and then I will practice tonglen. I’m gonna breathe in all the suffering, the anger, the pain, the confusion, and I’m gonna breathe out healing and peace and wisdom and love and strength. And that helps me, and it feels like I’m doing something, as opposed to just taking in all this horror and sorrow and sorrow. And you can practice it throughout your day. I don’t know if it’s the same for you, but every 15 minutes, I’m shocked at it, actually; that’s why I found a really quiet place in the house. But every 15 minutes I hear a siren or a cop siren; so, ambulance siren or cop siren.

Tippett: You’re in LA? You’re in LA County?

Banhart: I’m in LA, in East LA, and I don’t know if it’s somebody that’s — is it the ambulance, going to pick up a body? Is it somebody that’s sick and needs immediate, critical, emergency care? Or is this a crime? I’m not entirely sure, but it is consistent. It is every 15 minutes. And it began when this began. And so what do you do? I hear it, and I’m, “OK, I can practice tonglen.” This is a way of somehow being proactive amidst the helplessness of so much suffering and horror around you.

Now, this is the deep, kindergarten version of it. And I’m really, fully, lay practitioner 101.

Tippett: Well, for doing the 101 tonglen, the way you described it really corresponds to how I feel Pema Chödrön describes it in this book. Do you want to read some from that chapter, “The Love That Will Not Die?”

Banhart: Absolutely. Chapter 14, “The Love That Will Not Die.”

“The father of a two-year-old talks about turning on the television and unexpectedly seeing the bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City. He watched as the firemen carried the limp and bloody bodies of toddlers from the ruins of the day-care center on the building’s first floor. He says that in the past he was able to distance himself from other people’s suffering. But since he’s become a father, things have changed. He feels as if each of those children were his child. He feels the grief of all the parents as his own grief.

“This kinship with the suffering of others, this inability to continue to regard it from afar, is the discovery of our soft spot, the discovery of bodhichitta. Bodhichitta is a Sanskrit word that means “noble or awakened heart.” It is said to be present in all beings. Just as butter is inherent and milk and oil is inherent in a sesame seed, this soft spot is inherent in you and me.”

Tippett: I love that, “this kinship with the suffering of others.”

Banhart: I love that, too. I love that, and also, this is — maybe, at first, you go, What is this? What am I talking about, “bodhichitta”? [laughs] And then all we know, all we hear — then, later, we see, this is a Sanskrit word, and it just means noble or awakened heart. And it’s something we all have. That’s it. This is not some exclusive thing. [laughs] Something we all have. Talk about hopeful; talk about something to be like, whoa, turns out I have this thing already. This noble or awakened heart is there.

[music: “Bedroll” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today I’m with musician Devendra Banhart. We’re talking through our favorite passages of When Things Fall Apart, a classic, spiritual work by Pema Chödrön.

Tippett: And this thing that she goes on to talk about in this chapter is that — so, as you say, we all have this; we have this ability, this softness, this ability to know, be present to, to be in kinship with the suffering of others. And yet, as we all, also, reflexively understand, it just feels like too much, as you said. Reading the newspaper — I’m gonna try the tonglen, [laughs] because I can’t read it. I can’t read it all anymore.

But, she says, we think that by protecting ourselves from suffering — which, I think, is what I’m doing when I’m just turning off the news — is, she says, “We think that by protecting ourselves from suffering, we are being kind to ourselves. The truth is, we only become more fearful, more hardened, and more alienated. We experience ourselves as being separate from the whole. This separateness becomes like a prison for us, a prison that restricts us to our personal hopes and fears, into caring only for the people nearest to us. Curiously enough, if we primarily try to shield ourselves from discomfort, we suffer.” [laughs]

So, when you’re practicing tonglen, reading the newspaper or whatever — she talks about this as a practice that you can do while you’re — that it can be ordinary. It can also be — somewhere, she says — brushing your hair, listening to the rain, making music, [laughs] which you have some experience at. So it’s just a frame of mind with which you approach something? Or, is that how it starts?

Banhart: Kind of; it’s definitely also a way of unburdening yourself from yourself, too, because it’s a relief to care about somebody else. Really, it’s a relief to realize that — to get out of your head, too. So like I say, I don’t know if it is helping that person that I’m sending that wave of love, of strength, of wisdom, of healing — I don’t know if it’s helping them. But it helps me. And that’s the 101 kind of place to be, because — you know that classic story of when the airplane is — there’s no oxygen, you don’t put the mask on the kid first; you put it on yourself, and then you can put it on the child. And it’s like, OK, you have to kind of work on yourself, in order to be able help others. And tonglen is a really, really wonderful way of having a kind of consistent practice of getting out of yourself and being compassionate for others and remembering that there are other human beings on this planet, because there is no shortage of the opportunity [laughs] to work on it, and especially, not now — especially now, there’s no shortage. We have no shortage.

That’s why there is this sledgehammer of now-ness: whoa, this is this constant thing that is happening, and it is not just going away because we want it to. We’re really forced to lean into the sharp edges more than ever. We are standing on a sharp edge. We are sitting on it. [laughs] And the really cool thing about Pema Chödrön’s wisdom-style, is about — it’s about, be curious. There’s a kind of underlying, approach this fear, and approach this anxiety, and approach this heartbreak with curiosity — like, oh this is interesting. I’m an interested tourist here, checking it out, taking photos. I don’t actually live in this place.

Tippett: Because it is happening, whether you want it to or not, whether you like it or not. It is happening.

Banhart: Exactly. And can I approach it with this curiosity — whoa, this is happening — or, Argh, this is happening. This is this attitude, and I just have a little bit more curious feeling about it. And then I can let the wave pass, because wow, I don’t think I’ve ever personally felt, nor had — my friends and family feel so completely distracted and focused at the same time, and so completely exhausted and weirdly energized at the same time, and so completely overwhelmed by uncertainty and fear than now. And it’s this tidal wave. And so I’ll get a call or a text, and they’re going through the tidal wave: What is gonna happen? What’s gonna happen? And at that moment, maybe I’ll be in this feeling of Hey, it’s OK. I feel pretty calm. I can accept that I never know what’s going to happen, actually. So I can talk them through the tidal wave. And then I’ll need to call someone, because I’m going through the tidal wave. But, through it all, if I can remember Pema’s cool wisdom-style of curiosity, like, Oh, OK, I’m in a wave; this is interesting; oh, OK …

Tippett: And also what I like about that is — and this, I think, is true of spiritual disciplines and spiritual practices and virtues — what did you say — the superpowers of gratitude and patience and hope? — that in any given moment, carrying any of those is too much to ask of somebody, maybe in any given year. But we also carry them together, right? And the one phone call, you’re able to be present to that, and then somebody can offer you that gift, none of this spiritual wisdom or spiritual resiliences follows the American rules of being self-made men. [laughs] Some of the ways we’ve just been trained, culturally, get in the way of grasping what this is about. It’s not about being heroic — it’s not about being heroic. It’s not about being saints.

Banhart: And, you know, that American thing definitely isn’t just American. [laughs] I’d say it’s a global thing, this global — I don’t know in what country are children taught that they can find strength in vulnerability; it’s OK not to know; it’s OK to cry — these things are just, whoa, I don’t know where they tell them that. You have to — that’s why this book is so amazingly helpful, because it’s just so fully applicable on a very universal platform.

Tippett: I was thinking, when you were speaking a minute ago about — there were a couple passages I marked, right at the beginning of the book, in the “When Things Fall Apart” chapter, that I thought I might read. And then I was actually gonna ask you to read something. Well, I just want to say, before I do this, I’ve been listening to a lot of your music, just had it on in the background constantly …

Banhart: Oh, things are tough enough. You don’t really need to add that burden on yourself.

Tippett: [laughs] No, it’s been so wonderful. But you know your song “The Body Breaks,” which is — I feel like so much of the weird thing that we shouldn’t have to wake up to, but that we do, is that we inhabit bodies and that they’re frail and — it’s just this truth in our midst. And that song — and it’s also so beautiful, such a beautiful thing that gives us such pleasure and — I don’t know, I feel like that song evokes all of that right now in a way that it probably wouldn’t have. If we weren’t in the midst of a pandemic, it would be landing differently in me.

Banhart: Well, thank you for saying that. Thank you.

Tippett: So maybe I’ll read a few of these parts from “When Things Fall Apart,” just because I just want to read them and see if they — they struck me, when I was getting ready. “Things falling apart is a kind of testing and also a kind of healing. We think that the point is to pass the test or to overcome the problem, but the truth is that things don’t really get solved. They come together and they fall apart. Then they come together again and fall apart again. It’s just like that. The healing comes from letting there be room for all of this to happen: room for grief, for relief, for misery, for joy.”

A little bit later on, she says, “The only time we ever know what’s really going on … the only time we ever know what’s really going on — is when the rug’s been pulled out and we can’t find anywhere to land. We use these situations either to wake ourselves up or to put ourselves to sleep. Right now — in the very instant of groundlessness — is the seed of taking care of those who need our care and of discovering our goodness.”

Banhart: Amen. [laughs] That passage is perfect. Perfect.

And there’s also something really, really hopeful, in that when you initially read, “Things come together, and they fall apart,” there’s that sorrow — “No, I don’t want it to fall apart. I want to hold onto that good thing.” But then look at it inversely, and it’s like, this time will pass. This is gonna fall apart, too; this thing we’re going through, this pandemic, it will fall apart.

Tippett: [laughs] The falling apart will fall apart, too.

Banhart: So that’s nice. We can embrace, we can celebrate that, because it’s a fact. Things fall apart. [laughs]

Tippett: This is, in my version, these are the last two paragraphs of the “The Love That Will Not Die” chapter.

Tippett: Would you — I would just love to hear you read these two paragraphs.

Banhart: Of course. “Spiritual awakening is frequently described as a journey to the top of a mountain. We leave our attachments and our worldliness behind and slowly make our way to the top. At the peak we have transcended all pain. The only problem with this metaphor is that we leave all the others behind — our drunken brother, our schizophrenic sister, our tormented animals and friends. Their suffering continues, unrelieved by our personal escape.

“In the process of discovering bodhichitta, the journey goes down, not up. It’s as if the mountain pointed toward the center of the earth instead of reaching into the sky. Instead of transcending the suffering of all creatures, we move toward the turbulence and doubt. We jump into it. We slide into it. We tiptoe into it. We move toward it however we can. We explore the reality and unpredictability of insecurity and pain, and we try not to push it away. If it takes years, if it takes lifetimes, we let it be as it is. At our own pace, without speed or aggression, we move down and down and down. With us move millions of others, our companions in awakening from fear. At the bottom we discover water, the healing water of bodhichitta. Right down there in the thick of things, we discover the love that will not die.”

[music: “The Body Breaks” by Devendra Banhart]

Tippett: Devendra Banhart is a singer-songwriter and visual artist. He’s released ten albums including Rejoicing in the Hands, and most recently, Ma.

Special thanks this week to Nikko Odiseos and Katelin Ross of Shambhala Publications for their generosity in granting us permission to excerpt from Pema Chödrön’s When Things Fall Apart.

[music: “Abre Las Manos” by Devendra Banhart]

The On Being Project is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Laurén Dørdal, Erin Colasacco, Kristin Lin, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Serri Graslie, Colleen Scheck, Christiane Wartell, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, and Jhaleh Akhavan.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by PRX. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation. Dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections