Marilyn Nelson

Communal Pondering in a Noisy World

Marilyn Nelson is a storytelling poet. She has taught poetry and contemplative practice to college students and West Point cadets. She brings a contemplative eye to ordinary goodness in the present and to complicated ancestries we’re all reckoning with now. And she imparts a spacious perspective on what “communal pondering” might mean.

Image by Thái An/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Guest

Marilyn Nelson was born in Cleveland, Ohio, the daughter of a school teacher and a U. S. serviceman, a member of the last graduating class of Tuskegee Airmen. She is the author or translator of more than 20 books and chapbooks for adults and children. A professor emerita of English at the University of Connecticut, Marilyn was Poet Laureate of Connecticut, 2001– 2006, and founding director of Soul Mountain Retreat, a writers’ colony, 2004-2010.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: Marilyn Nelson is a storytelling poet. She gives winsome voice to forgotten people from history — and from her own family. She shines a light on the complicated ancestry we have in common and that can help us in the work we have to do together now. She’s written for both adults and children. She’s taught poetry and contemplative practice to West Point cadets. And alongside the gentle but mighty esteem Marilyn Nelson commands in the communion of modern poets, she’s a voice for all of us in the work and the privilege of what she calls “communal pondering.” To sit with her is to gain a newly spacious perspective on what that might mean — and on why people young and old are turning to poetry with urgency.

Marilyn Nelson: Poetry consists of words and phrases and sentences that emerge like something coming out of water. They emerge before us, and they call up something in us. But then they turn us back into our own silence. And that’s why reading poetry, reading it alone silently takes us someplace where we can’t get ordinarily. Poetry opens us to this otherness that exists within us. Don’t you think? You read a poem and you say, “Ah.” And then you listen to what it brings out inside of you. And what it is is not words; it’s silence.

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Marilyn Nelson is professor emerita of English at the University of Connecticut, and a former chancellor of The Academy of American Poets. I interviewed her at the University of North Carolina Asheville in 2016.

Tippett: So, here we are. And I’m just delighted to be up here with Marilyn Nelson. It’s been such a treat to be reading your poetry these last few days.

Nelson: Thank you, Krista.

Tippett: You were born in Cleveland of a teacher mother and a father who was a member of the last graduating class of the Tuskegee Airmen. And I wonder — and you were moving around a lot.

Nelson: A lot.

Tippett: Yeah. You and your sisters always imagined that, when you left each place, it disappeared, ceased to exist. [laughs] And you did — this book, How I Discovered Poetry, it’s a memoir in poems, right?

Nelson: Yes.

Tippett: And I just wondered — so I want to say, I said to Marilyn — I have a few books here. And I have some — we’ll read some poetry throughout. I’m going to ask her to read some things. We’ll read some at the end. But I also said to her that, if she just feels called to grab one of these books and read, she can. But I wondered if you would just read the last poem in this collection, How I Discovered Poetry.

Nelson: Yes, OK. This one is called “Thirteen-Year-Old American Negro Girl.” Each of these poems has a little byline of where we were at the time this — we were on an air force base in Oklahoma in 1959. “Thirteen-Year-Old American Negro Girl.”

“My face, as foreign to me as a mask, / allows people to believe they know me. / Thirteen-Year-Old American Negro Girl, / headlines would read if I was newsworthy. / But that’s just the top-of-the-iceberg me. / I could spend hours searching the mirror / for clues to my truer identity, / if someone didn’t pound the bathroom door. / You can’t see what the mirror doesn’t show: / for instance, that, after I close my book / and turn off my lamp, I say to the dark: / Give me a message I can give the world. / Afraid there’s a poet behind my face, / I beg until I’ve cried myself to sleep.”

Tippett: Thank you.

Nelson: That’s my sister banging on the bathroom door. [laughter]

Nelson: And I don’t know — do you want me to talk about it? For me, the crux of this poem is the fact that I really did pray, “Give me a message that I can give the world.” If you give me a message that I can give the world, I promise I’ll be true to it. I will be honest to it. That was my 13-year-old prayer. “Let me be a poet. Give me something to share.”

Audience Member: Right, so it came true. Praise God. [laughter]

Tippett: Yeah, I think you did it.

Nelson: Thank you.

Tippett: I’ll take this back, but you can grab it anytime. And is this one that you wrote — it feels to me, like, in a lot of your poetry, there’s a public life implication, even if it’s not a — even in that poem you just read. Is this a poem that you wrote at age 16, “Here in Democratic Dominion?”

Nelson: Yeah. Oh, yeah. Where did you find that one? [laughs]

Tippett: Lily helps me prepare. “Here in democrat dominion, / each man has his own opinion. / He can argue loud and long: / he has a right to his own wrong.” [laughter]

Tippett: This is why we’re putting poetry on the air during election year. [laughs] But you know, you put poetry to family and history, to love and lynching, to motherhood and monasticism. I had a conversation with Paul Muldoon early this year, and he said — he loves music. He’s also the poetry editor of The New Yorker. And he said, “Americans think they don’t read poetry, but they walk around singing poetry all the time.” Our music carries poetry.

I did see that you worked with Lutherans after college, to that point, and you were invited — and you were a poet, and you were invited to serve on the hymn text committee, which is another way people in churches walk around with poetry, not calling it that. And you revised every text in the hymnal trying to remove traces of racism, sexism, and militarism.

Nelson: Yes. It was a huge job. [applause]

Nelson: Try to remove militarism from “Onward Christian Soldiers.” [laughter]

Nelson: It was a job the — if there are Lutherans here, it’s the green hymnal — is the one that I worked on, and it was really a challenge. I was a kid. The other people on the committee were theologians and ministers with years of experience in congregations, but I was good at rhyming. [laughs]

Tippett: [laughs] You also write a lot about family. I think writers in general, but poets in particular have this exquisite tool for kind of getting inside the deep meaning of family and not having to make it neat and tidy. The Homeplace is your — are your poems — where you really went back to the history, your lineage really. I mean, just to give a little bit of description — these are very lively characters.

These are a few generations of your family and aunts and grandmothers, and it’s the things that are happening in the world around them. It’s what they’re having to reckon with, including the Ku Klux Klan. But it’s also having babies, living in big, boisterous families, serving in the army, falling in love. Who was it — Aunt Geneva who was the wild one, fell in love with a white man. You have a character in there during the Civil War era named Henry Tyler.

Nelson: Ah, yes.

Tippett: He’s a complicated character.

Nelson: Complicated — yeah.

Tippett: And you let that be there. You just let that be there. Also, in the life of your family and your great grandmother, was it?

Nelson: Yes, yes. I mean, American history, especially in the South, goes across a lot of lines that we imagine are impermeable. They weren’t impermeable. And my family believes one of our ancestors was this white man, Henry Tyler, and that the relationship he had with our foremother was — she didn’t belong to him. It was during the years of slavery. But my family believes that this is a love story. And my cousin and I went to the town our family comes from. And of course, a lot of the old records have been burned, destroyed, but we did find a deed for a house in which he gave our foremother, Diverne, a house. And we take that to be some indication that the story we had inherited was a true story, that there was some kind of relationship there. Who knows what could’ve happened, what kind of relationship was possible at that time? I don’t know.

Tippett: But you also — he was a terrible racist and also a symbol, in many ways — or an example of …

Nelson: Yes. He went on to become a state senator or a state representative. Yeah, and he had been a part of, what’s his name, Raiders — Forrest Raiders. That’s a famous — I can’t remember his name, and I’d have to read the whole book to find it. But this man, somebody Forrest, who was a colonel or something in the Confederate army and our — this Henry Tyler fought under him. And this man, Forrest, our maybe purported forefather went on to have a career in politics in Kentucky. But this man, Forrest, became the originator of the Klan. So he went in that direction.

I don’t know — I mean, these are things are that are verifiable. The relationship is not verifiable. I have — we just don’t have any way of knowing things like that, other than DNA. And what we do know, luckily for me, in writing this book, is that our family, we are the only descendants of this Mr. Tyler. He had children — he married later and had a couple of children, but they all died without issue. So if he was our forefather then we are the only ones.

Tippett: He lives on through you.

Nelson: Yeah.

Tippett: I also read that interview in Image, which was wonderful, which was referenced, and they asked you about the years in which you were teaching, writing, parenting a child at the same time. And I just want to read what you said. You said, “My book Mama’s Promises describes a lot of my experience during that period. I came up for early tenure in an almost exclusively white, male English department when my son was about fifteen months old. I was unhappily married, new to the community, and had few friends. Though I had published a book of poems with a major university press, and had poems in several major press anthologies of younger American poets, I had to fight for my life because my colleagues considered poetry inferior to literary criticism. I spent several years writing poems at three a.m. because I had to do class preparations first. I went to the ER several times with heart palpitations caused by stress. Meanwhile, my mother was disappearing into Alzheimer’s disease.”

And then you said, “I would not want to relive that period of my life. But I kept thinking of my great-great-grandmothers.”

Nelson: Yes. I kept thinking if they could live through what they lived through, I can live through a tenure decision. Piece of cake. [laughter]

[music: “Fagerhult” by Lambert]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, I’m with the storytelling poet Marilyn Nelson.

[music: “Fagerhult” by Lambert]

Tippett: I want to talk about your understanding of the relationship between poetry and silence. You said poetry comes out of silence. Would you talk about that?

Nelson: Yes, I think poetry comes out of silence and leads us back to silence. It should, I think, lead us back to silence. Silence is the source of so much of what we need to get through our lives. And poetry consists of words and phrases and sentences that emerge like something coming out of water. They emerge before us, and they call up something in us, but then they turn us back into our own silence. They — it’s a gift, in a way. It’s a gift out of a kind of universal silence that takes us into a private silence, I think.

And that’s why reading poetry, reading it alone silently takes us someplace where we can’t get ordinarily. Poetry opens us to this otherness that exists within us. In any case, I think poetry and the silence of the inner life are related, are connected and that — don’t you think? You read a poem, and you say, “Ah.” And then you listen to what it brings out inside of you. And what it is is not words; it’s silence. So, yes.

Tippett: I wonder if that’s one way to talk about what’s happening when — I mean, my experience when we put poets on the air is that people respond like they were starved for this and they didn’t know it. And you’re very winsome about how you love technology in many ways, and yet, the presence of technology and the pace of our lives makes silence this endangered thing that we do have to intentionally create it, create spaces for the possibility of it. And I don’t think that was always true in human history.

Nelson: Oh, I think it’s more and more difficult to find silence. You go anyplace, restaurant, an airport, and people are all figuring out ways to fill up the silence with some kind of technology. They’re listening on earphones. They’re looking at smartphones. And I think this is a terrible thing. It frightens me. I think we’ve become afraid of silence.

Tippett: Well, it’s not necessarily a comfortable thing, right? So the technology is there to rush into that — meet the discomfort. But I mean, so you actually have — you’ve worked with contemplative practices with your teaching. And maybe that’s partly what you’re doing. You’re helping people sink into that, or that’s one thing contemplative practices do for us.

Nelson: Yes. And I think people are starved for that too. The times that I’ve offered a few minutes of meditation at the beginning of a class. Just say we come into a classroom out of who knows what. We come into a classroom, and then we are immediately starting to talk about something. Let’s not bring all of the noise of the outside world into this classroom. Let’s release it and enter into silence. And I’ve had students love doing that. Nobody’s offered them — has been quite a lot of recent research about the effect of contemplation, meditation, silence.

Tippett: Right. The research has caught up with you now.

Nelson: Yeah. How much it enhances the learning experience. And I think that’s what I’ve been trying to offer students in my classrooms. I’ve had a lot of wonderful, beautiful results.

Tippett: So I’m really intrigued that you — was West Point one of the places you started doing this?

Nelson: Yeah, that was the first thing I did. Yes.

Tippett: And so you said there was a — you got a contemplative practices fellowship — and I’m not sure what that means — right as you were starting to teach at the U.S. military academy at West Point. So, I mean, tell us about that experience.

Nelson: It’s an organization called the Center for Contemplative Life, Contemplative Mind and Society. Shortly — I don’t know — I applied for the fellowship, and then I was invited to West Point to do a reading. And after the reading, they asked me if I would be interested in teaching there. And I think the next day, I got the news that I had won this fellowship. So I said, “I’ve won this fellowship.” And they said, “Bring it here. Do it here.”

So I wound up teaching two sections of a course on poetry and meditation to cadets at West Point. It was — it makes me want to cry. It was an absolutely wonderful experience. I loved the cadets. We would come into the classroom, close the door, turn off the lights, and meditate for five minutes at the beginning of the class. And then I asked them to meditate for 15 or 20 minutes every day outside of class, which was very hard for them.

Their lives are scheduled. Every minute is scheduled. Finding 10 or 15 minutes and a quiet place was really a stretch for them. But they did it, and they kept journals. And their journals showed so much growth during the course of that semester. And I loved them. I remember we made up mantras to meditate with. One of them made up a mantra, “To swim in a heartbeat of clouds.” Yes. So yeah, it was a…

Tippett: I was also really intrigued that — it sounds like you coupled that — like, you explored also where that takes people and you use words like “musings” and “communal pondering,” that in those classes, you ended up having these conversations about Just War Theory that came — that probably would’ve been very different if the conversation hadn’t started in that silent, grounded, contemplative place. Even the notion — I mean, the phrase “communal pondering,” I feel like that’s what we need as a nation right now. Right? We have no idea how to do that, but it sounds so fascinating.

Nelson: It’s maybe one of the things we’re doing in poetry readings. I just was, last night, at the Dodge Festival, Geraldine Dodge Poetry Festival in Newark. And the chancellors of the Academy of American Poets read last night. There are 12 chancellors so 12 readings, each — I think each reading was seven minutes. It was communal pondering. The poets were different. The voices were different.

And every one of the poems took us someplace that brought something out of us, from poems about — I remember Mark Doty read a poem about his — he writes a lot about dogs, so we had a couple of dog poems. We had poems about grandparents. We had poems about losing friends. We had Anne Waldman who read a Tibetan — it was her own poem, but it was based on a Tibetan Buddhist chant, I think.

It was wonderful, and it was a way of sitting and pondering together. And I think it’s a very rewarding activity. One of my college professors said that poetry rediscovers reality for us. And in a way, that’s what happens. You go to listen to a poet, and you leave not only having learned something about the poet’s reality, but also having learned something about the reality you are living. And I guess that’s what communal pondering is.

Tippett: To that point — I don’t know if this is something you’re aware of — we found this blog post that was written actually by a professor who had just gotten back from sabbatical, and she was dusting her office. Have you read this? I mean, this is the things you can find on the internet. This is the upside of the internet. Is your poem, “Dusting?”

Nelson: Mm-hmm.

Tippett: It’s a small poem. I don’t know if this is the whole thing. You want to read it?

Nelson: Oh, she put it on her blog?

Tippett: She put it on her blog, so I’m going to — I’ll read what she wrote. She wrote — the blog title was “The Spiritual Case For Dust.” [laughter]

Tippett: But why don’t you read it, and then I’ll read what she said.

Nelson: OK. It’s a part of it. I don’t remember…

Tippett: It’s just a part of it?

Nelson: “Thank you for these tiny / particles of ocean salt, / pearl-necklace viruses / winged protozoans: / for the infinite / intricate shapes / of submicroscopic / living things.”

Tippett: And she wrote, “Nelson’s poem and my dusty office reminds me that the unpolished and ordinary is cloaked in the extraordinary. Even as I settle back into my everyday life, in that dust, tiny tokens of the universe have settled into my office. Should I be able to sort through the motes, I expect I would find fragments brushed from the cliffs in Ireland blown into the air by storms in the Pacific, and burnt off comets that blundered into Earth’s atmosphere. Crumbs of the infinite lie scattered across my desk. I’m suddenly hesitant to pick up my dust rag and wipe it all away.” [laughter]

Nelson: Yes, I read someplace that dust is one of the cleanest things on the planet, and we — yeah. You can wash in dust and that we can’t have rain without dust. Dust seeds clouds so that rain happens. We wouldn’t have rain without dust, which I think is beautiful. And that dust is full of life, that the things listed in my poem are things that are in dust, that dust is alive. Sharon Olds, a really terrific poet, told me once that she had named the dust bunnies in her house. [laughter]

Nelson: Yeah, we need to do that.

[music: “Valley of Gardens” by Teen Daze]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Marilyn Nelson. You can always listen again, and hear the unedited version of every show we do on the On Being podcast feed — wherever podcasts are found.

[music: “Valley of Gardens” by Teen Daze]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, as Americans young and old are reaching for poetry with a new intensity, I’m with the storytelling poet Marilyn Nelson. She’s taught poetry and contemplative practice to West Point cadets. She commands gentle but mighty esteem in the communion of modern poets, and she’s a voice for all of us in the work and privilege of what she calls “communal pondering.”

Tippett: So contemplative prayer is part of your life. Is that right? Is it?

Nelson: Well, yes, I’m more of a backslider than …

Tippett: OK, OK. Well, let’s say it’s something you’re drawn — you’ve been drawn to. Would that be fair?

Nelson: I have been drawn to it, yes. And my friend, who is a former monk and who travels around teaching meditation …

Tippett: Is this Father Abba Jacob.

Nelson: Abba. Yes.

Tippett: He’s a pretty intriguing character in your writing.

Nelson: He is a very intriguing character. He says that meditation, after you’ve practiced, it’s an attitude. It’s not — you don’t have to sit in a certain way and hold your hands in a certain way. It’s an attitude. You look at the world with this attitude. In a similar way, I was thinking today, earlier, about methods of prayer, which I’ve found just beautiful and meaningful. One of them is the prayer of just gratitude, just feeling grateful.

And one of them is a prayer I found in a book by a nun who lives as a hermit. I don’t remember her name or the name of the book. But she offers a kind of prayer which she calls the prayer of the loving gaze. It’s a prayer. Just put your love into your eyes and just look at the world with that gaze and that’s what contemplation is about, really. It’s learning how to find that gaze in yourself and to put it in the world.

Tippett: I’d love to delve into Abba Jacob a little bit. So he’s a real person. He sounds like a desert father when you — right, even Abba Jacob, calling him that.

Nelson: Yeah. Well, that was…

Tippett: He sounds like one of these hermits who could’ve been living in the deserts of Egypt.

Nelson: Yes. Well, the first time I visited him — he’s someone I met when we were in college together. And 20 years later, I found him living as a hermit, and I went to visit and…

Tippett: Oh, you were at college with him?

Nelson: We were in college together.

Tippett: Really?

Nelson: Yeah, we met 50 years ago.

Tippett: I mean, you have all these — this is in this collection, Faster Than Light: New and Selected Poems. You have kind of an Abba Jacob section here called “How To Be Human Now,” which is also just such a wonderful line. I guess it’s from Auden. “To discover how to be human now / is the reason we follow the star.”

Tippett: Here’s another — here’s one — I want to ask you about this, another poem you wrote about him. “Abba Jacob said: / There’s a big difference between / the mentalities of magic and of alliance. / People who spend their lives searching for God have a magical mentality: / They need a sign, a proof, / a puff of smoke, an irrefutable miracle. / People who have an alliance mentality / know God by loving.”

I’m really intrigued by that phrase, “an alliance mentality.” What do you mean by that?

Nelson: I think people who have a “magic mentality” believe that God is something out there that we have to find to connect with and people who have an “alliance mentality” know that God is inside of us and in our connections with each other and with the world, that God exists within and between, not exterior to us, but within us and between us. I think that’s what he was trying to say.

Tippett: So we are allied with whatever God is.

Nelson: Yes.

Tippett: And with everything we’re part of.

Nelson: Yes. There is no separation. We are a part of God. That’s — isn’t that the ecstatic experience? We recognize that. And some people know that just naturally. Other people have to learn it.

Tippett: I wonder if you’d read a couple of poems. There’s a poem in here called “Farm Garden,” which just struck me.

Nelson: Is it in that book?

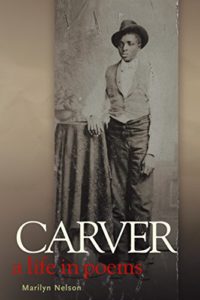

Tippett: It’s in this one. Yeah. It’s “Lyric Histories.” Is it about George Washington Carver? You have said that that — writing about George Washington Carver changed you.

Nelson: Yes. No, this isn’t from Carver. And that did change me, but — it really did.

Tippett: But why? What was it about that?

Nelson: I had been writing a series of poems about radical evil. And I could see that whatever we discover, whatever evil weapon we discover, somebody’s going to use it. There is no limit to our capacity for evil. And I wanted to look at a saint’s life to ask whether there is any limit to our human capacity for good. And Carver’s life showed that capacity. He lived what he believed. He lived his faith. And I believe he was a saint.

But this poem here is from a different project. It’s about the life of Venture Smith, who was enslaved in Connecticut in the 18th century. He was captured as a boy in, I think, Ghana, brought to North America as a slave, served for about 30 years under several different masters in Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New York. And then he purchased his own freedom, and then he purchased his children and his wife, and then he went into the freedom business, saving up money and setting people — buying people so he could set them free. So this is from his life.

“By the time I was thirty-six I had been sold / three times. I had spun money out of sweat. / I’d been cheated and beaten. I had paid an enormous sum / for my freedom. And ten years farther on I’ve come / out here to my garden at the first faint hint of light / to inventory the riches I now hold. / My potatoes look fine and my corn, my squash, my beans. / My tobacco is strutting, spreading its velvety wings. / My cabbages are almost as big as my head. / From labor and luck, I have much profited. / I wish I could remember those praise-songs / we used to dance to, with the sacred drums. / My rooster is calling my hens from my stone wall. / In my meadow, my horses and my cows look up, / then graze again. My orchard boasts green fruit. / Yes, everything I own is dearly bought, / but gratitude is a never-emptying cup, / my life equal measures pain and windfall. / My effigies to scare raccoons and crows / frown fiercely, wearing a clattering fringe of shells, / like dancers in the whatdidwecallit? dance. / My wife and two of my children stir in my house. / For one thirty years enslaved, I have done well. / I am free and clear; not one penny do I owe. / I own myself—a five-hundred-dollar man— / and two thousand dollars’ worth of family. / Of canoes and boats, right now I own twenty-nine. / Seventy acres of bountiful land is mine. / God or gods, thanks for raining these blessings on me. / I turn around slowly. I own everything I scan.”

So the narrative of Venture Smith’s life was published in, I think, 1795. It’s one of the rare stories in African American history. This family, Venture Smith’s descendants, have been free for eight and nine generations. There is an annual Venture Smith Day in East Haddam, Connecticut at the Congregational Church he belonged to and is buried in the cemetery there.

Now, there are scholars who are coming to talk about new discoveries of his life, and his descendants come. Last year, or maybe the year before, Venture Smith’s descendants went to Ghana to the castle he remembered being shipped out of. They were there, nine generations free. It’s such a wonderful story. And it’s what American history could have been. It could have been that way. But this is a man who did this for himself.

[music: “The Wider Sun” by Jon Hopkins]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, I’m with the storytelling poet Marilyn Nelson.

[music: “The Wider Sun” by Jon Hopkins]

Tippett: Somewhere you said, “There are so many interesting stories. I’m sorry I can’t write about all of them.” And I think we get that. And there’s so many stories that you’ve written about — you wrote a children’s book about Emmett Till, but really also about his mother. I mean, there’s so many stories, your own from your own family and other families. I wonder, through all of this, and this is a vast question, but how you would just start to answer, like how your sense has evolved, how you think about what it means to be human, what this life in poetry and storytelling has taught you about that.

Nelson: I think I’ve become more open to history, to other people’s histories. When I started, I was writing about my own life and the life of my family. The last two projects I’ve done have taken me quite a distance away from those interests. One of the two most recently published books I’ve written are — one of them is a history of the first 200 years of the First Congregational Church of Old Lyme, Connecticut. Old Lyme, Connecticut is a community that has been populated for the — probably the last at least 120 years by the families of sea captains, whaling captains. It was a very prosperous community.

And this Congregational Church started in that way. It was founded in 1666, and the first church divided the congregation with the women and girls sitting in the front, and men sitting behind them, and then boys and servants and slaves sitting in the back. That’s how it began. The first minister of the church raised his children with the help of Arabella, his slave. That’s where it started. And working with this specific history of a prosperous New England town, seemed to me to be teaching me something about our nation, where we started, what we’ve gone through, the wrenching of our history.

And this church now, 350 years after its founding, with the first minister keeping slaves in the attic of the parsonage — one of the ministers took off for a year off of his ministry to go and fight the Niantic Indians. This community now has a relationship with the Lakota community in North Dakota, so there are people going back and forth from the church and the reservation every year. They have a relationship with the only tuition-free private school in Harlem. I mean, this is a community that has learned how to be what they have always thought they were, but couldn’t see.

But then, you know they had to learn. In the last 80 or 100 years, they’ve learned how to be a church, a true church in the course of this 350 years. They really had to struggle. They really had to struggle. What does it mean? How do we live out the faith we claim? How do we bring it into the world? And it’s not easy. It’s not easy. There are always people who want the safe route, who think that doing unto others means doing unto others who are like you.

But working, trying to struggle with real history has been a way to learn something about who we are, I think, less personally, less who I am than who we are as a nation. What are we doing here? And how is it that we have managed to persist in the blindnesses that we started out with? How are we back to our campaign? How are we able to lie to ourselves like that?

Tippett: Yeah. But what I think the stories you’re investigating and telling are also true about what we’re capable of. And it’s important that we see the fullness of what’s possible.

Nelson: I think so, yes. The good stories, the stories of people who do something wonderful, but ordinary. And people do wonderful things and then they say, “I only did what seemed like the obvious thing. I didn’t really choose.” But most people don’t make choices like that. And I think we do, we need to tell their stories. We need to learn about people who are willing to put their lives on the line.

And we just had a conversation earlier today about one of these cell phone videos that was made in Edina, Minnesota in which an African American man is walking down the sidewalk. There was some kind of construction blocking the sidewalk, so he walked out into the street to go around the blockage, and a cop immediately stopped him and grabbed him and started pushing him around.

And there was a woman there who — you could hear in the voice. I visualize this woman. It’s a middle-aged, white, Minnesota woman. She gets out of her car. She starts recording this, and then she says, “But officer, I think you should — I think that you’re being unfair. I think you should help him,” in a kind of timid way, but she spoke up. This man could have been dead. He could easily have been dead for walking down the street. And yeah. So, I think we need to be telling these stories.

Tippett: And I think it also — it’s just an illustration of the ordinary interwoven with the extraordinary, which is really such a theme that runs all the way through your writing. There’s a poem that you wrote after Rilke, who I also love, which I think is in — it’s in the Fields of Praise book, page 152. Maybe you could read that to close. It’s just lovely and quite — it’s another one of your voices.

Nelson: Oh, all right. This is “Lovesong.”

“How shall I hold my spirit, that it not touch yours? / How shall I send it soaring past / your height into the patient waiting there / above you? Oh, if only I could shut / it up, leave it to gather velvet dust / someplace where it would echo you no more. / But like two strings vibrating as the bow / ripples them with a long caressing stroke, / we tremble, drawn together by one joy. / What instrument is this? Whose fingers make / a chord beyond our capacity for awe? / How sweet, how: Ah!”

[applause]

Tippett: Thank you.

[music: “What You Love You Must Love Now” by The Six Parts Seven]

Marilyn Nelson is a professor emerita of English at the University of Connecticut, and a former chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. She was awarded the Frost Medal, the Poetry Society of America’s most prestigious award, for “distinguished lifetime achievement in poetry.”

Her books include The Fields of Praise and most recently, The Meeting House. Her upcoming children’s picture book is about social justice and the power of introverts. It’s called Lubaya’s Quiet Roar and you can preorder it now. I interviewed Marilyn Nelson as part of the inaugural Faith in Literature Festival at the University of North Carolina, Asheville; a partnership with public radio station WCQS Asheville and the Wake Forest School of Divinity.

[music: “What You Love You Must Love Now” by The Six Parts Seven]

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation. Dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.