Matthieu Ricard

Happiness as Human Flourishing

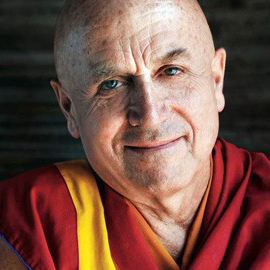

A French-born Tibetan Buddhist monk and a central figure in the Dalai Lama’s dialogue with scientists, Matthieu Ricard was dubbed “The Happiest Man in the World” after his brain was imaged. But he resists this label. In his writing and in his life, he explores happiness not as pleasurable feeling but as a way of being that gives you the resources to deal with the ups and downs of life and that encompasses many emotional states, including sadness. We take in Matthieu Ricard’s practical teachings for cultivating inner strength, joy, and direction.

Image by Matthieu Ricard, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Matthieu Ricard is the author of Happiness: A Guide to Developing Life’s Most Important Skill and Altruism: The Power of Compassion to Change Yourself and the World.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: Matthieu Ricard is a French-born, Tibetan Buddhist monk and a central figure in the Dalai Lama’s dialogue with scientists. He was dubbed “the happiest man in the world” after his brain was imaged. But Matthieu Ricard resists this label. In his writing and in his life, he explores happiness not as a pleasurable feeling but as human flourishing, a way of being that gives you the resources to deal with the ups and the downs of life and that encompasses many emotional states, including sadness. We experience Matthieu Ricard’s way of being, and we take in his very practical teachings for cultivating inner strength, joy, and direction.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

Matthieu Ricard: You cannot, in the same moment of thought, wish to do something good to someone or to harm that person. Those are mutually incompatible, like hot and cold water. So the more you will bring benevolence in your mind at every of those moments, there’s no space for hatred. It’s just very simple, but we don’t do that. We do exercise every morning, 20 minutes, to be fit. We don’t sit for 20 minutes to cultivate compassion. If we were to do so, our mind will change, our brain will change. What we are will change.

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

Ms. Tippett: Matthieu Ricard is the author of several globally best-selling books, and he is the French interpreter for His Holiness the Dalai Lama. He had a secular upbringing in France with his artist mother and a famous philosopher father. Growing up, he had lunch with the composer Stravinsky. The photographer Cartier-Bresson came for dinner at his family home. And Matthieu Ricard was surrounded in adulthood by brilliant scientists. He began his professional life at the cellular genetics laboratory of a Nobel Prize-winning biologist at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. Now he resides at the Shechen Monastery in Nepal, where he coordinates a number of humanitarian projects. I sat down with him in 2009 in Vancouver, Canada, at a gathering with the Dalai Lama, Nobel laureates, scientists, educators, and social activists.

Ms. Tippett: I interview people who do many different things and come from many different traditions and professions, and I always ask, as a starting question, if you’d tell me a little bit about the spiritual background of your life.

Mr. Ricard: Spiritual background.

Ms. Tippett: Yes, which, if you ask someone that in the United States, even if they’re not religious, you always get a really interesting story.

Mr. Ricard: Really?

Ms. Tippett: Yeah, really interesting. But I think in France it’s a different kind of question.

Mr. Ricard: You think it will be a not-interesting story? [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: I mean I know your father was a philosopher, but even was there any kind of secular spirituality?

Mr. Ricard: Well, not — I don’t know. Spirituality, for me, if you look at the roots, means something to do with the mind, dealing precisely with the mind and the way you experience the world. Well, I was just like any of those boys in France. I was raised completely agnostic. But when I was 15, 16, I started reading a lot. And also I had an uncle who was a great explorer, who is still alive. He’s 90.

Ms. Tippett: Right, what was he, a solo yachtsman or something?

Mr. Ricard: Jacques-Yves Le Toumelin. He was the last of the great solo navigators on sail without any engine. So he went around the world after the Second World War on a 10-meters-long yacht, and he was one of the four or five classics of those circumnavigators of the globe, taking their time, and beautiful adventures. So while he was doing the circumnavigation, he was also reading books about Hinduism, Sufism, and he became a kind of — I wouldn’t say mystic, but certainly it was something that we would discuss a lot when I was going for holidays in his home. So I started reading about all those great traditions, and even including Christian mystics, like the early orthodox writings and Meister Eckhart, and everything you can think of. And it’s something that really mattered to me. At the same time, there was no living tradition. There was no connection except to reading and discussions, which was — of course, it’s an important step.

Ms. Tippett: Right, but it was quite cerebral.

Mr. Ricard: Very cerebral, although there were some aspirations and some kind of respect, but I didn’t know how to formalize that. But I was still quite a sort of, politically, very leftist type.

Ms. Tippett: Yes — well, and also, really, when I read about your parents and the world you grew up in, it’s quite a charmed childhood. I mean you were surrounded by brilliant people and artists, great thinkers.

Mr. Ricard: Well, that recognition of the difference came a little bit later. So the turning point, the factual turning point: When I was 20, I then saw a series of documentaries with one of the Dalai Lama’s interpreters — for months and months, all the great masters of 2,000 kilometers of the Himalayas outside Tibet, the great Tibetan masters who had fled the Chinese invasion, from Bhutan to Sikkim to India to Dharamsala. And at the end of one of the documentaries, there was a series of faces of contemplatives, some great masters, some simple hermits, just in sort of meditation, looking straight at the camera — probably they were not looking at the camera, but they were meditating, and someone filmed them in silence and that sort of building up of the strength of those faces, the strength of their presence, the strength of the silence.

And what was also very remarkable is that they’re all very different physically — some very ascetic and skinny ones, some more round faces, some young, some older, but there was a common quality that’s hard to describe, but it’s something to do with inner strength, compassion, unwavering quality of awareness, and all those things which constitute a true spiritual teacher. And sort of like you hear about Saint Francis of Assisi, you hear about Socrates, you hear about Meister Eckhart, and you wonder how they look like. [laughs] And there, there was those alive now. [laughs] So I thought, I must go there. So there I was, going on the train in India and finding Darjeeling and meeting those great masters.

Ms. Tippett: I was really intrigued — let’s say this. I had a very different experience, but your story reminded me of this. When I was in my 20s, I was working in divided Berlin, and I ended up working in these very elevated circles of political strategy and military strategy. And my spiritual journey started when I kind of recoiled at the contrast between the importance of the issues and the intellectual and strategic substance of these people, the contrast between that and the very small inner lives a lot of them had. And I read a kind of similar observation that you wrote, because you were surrounded by it. I mean you met Stravinsky and Buñuel and — but you said, “You can be a genius in your field, and yet remain a dreadful person in daily life.”

Mr. Ricard: Well, yes, I don’t want only to accent the dreadful person. What I mean is that there was no obvious connection.

Ms. Tippett: Right. But so what’s so fascinating to me is, what you were attracted to was this embodiment, these lives of integrity. And it was really experiential, rather than intellectual, at that point.

Mr. Ricard: Yes, because it struck me. Retrospectively, almost, I started thinking, “Well, all these wonderful people, great scientists, musicians, philosophers, painters, ordinary folks, you find a good distribution of everything — wonderful warmhearted people, you feel so good to be with them, and then people who are grumpy and not very altruistic, and so forth. So therefore, it didn’t seem that to become a scientist or to become a philosopher will make you, necessarily, a good human being.

Now a spiritual teacher, if you say, “Oh, he’s a great spiritual teacher, but wow, besides that, he’s so grumpy,” it doesn’t work. [laughs] It can’t. This is not what you’re looking for, saying he’s an authentic spiritual teacher. So there has to be a perfect adequation, and also, it has to be not a facade. There are so many, unfortunately, of those who look very impressive, and then if you scratch a little bit the surface, or if you wait long enough, you will see that there are sides of them that don’t fit with what they are supposed be. So the messenger has to be the message, and it has to be integrally the message.

And what is most remarkable, having lived, then, for almost 40 years with great spiritual masters, is that, for instance, my second great teacher, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, who was one of the teachers to the Dalai Lama, and I was day and night with him, because I became a close disciple and attendant, one of the two monks who would — I would sleep in his room at night, help him to get up if he needed so. When he would wake up to do his meditation at 4:00 in the morning, I would wake up and serve him hot water, whatever — so all the time, when he was giving teaching, when he was traveling, when he was meeting kings, when he was meeting farmers. And over 15 years, to see that absolute coherence and consistency in every aspect of that person’s life — like the Dalai Lama, you see him in public, in private, in any circumstances, he’s just such an extraordinary, good human being. There’s no hidden side of it. So that was most inspiring, because you say, “That’s what I could become. Here is someone who did it, so therefore, it’s possible.” [laughs]

[music: “Mirrors” by Wes Swing]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, with Tibetan Buddhist monk and teacher Matthieu Ricard. He first became widely known in the West with the publication of the 1998 book The Monk and the Philosopher. It documents a dialogue between him and his father, who was a pillar of 20th-century French secular intellectual life. Asked by his father, as the dialogue opens, why he left his promising scientific career for a Buddhist path, Matthieu Ricard says this: “My scientific career was the result of a passion for discovery. Whatever I was able to do afterward was in no way a rejection of scientific research, but arose rather from the realization that such research was unable to solve the fundamental questions of life — and wasn’t even meant to do so. At the same time I was becoming more and more interested in the spiritual life in terms of a ‘contemplative science’.”

[music: “Mirrors” by Wes Swing]

Ms. Tippett: There’s a book that was published, which was in the form of a dialogue between you and your father. The Monk and the Philosopher, it was called. It’s really clear that he was very proud of you. He was very proud of what you were accomplishing.

Mr. Ricard: Well, not in the beginning.

Ms. Tippett: Well, nobody — when you were heading towards your career in science as a cell biologist, and you presented your dissertation to Nobel winners, and you were working in the Pasteur Institute, and then, he writes, “you abandoned your career in order to commit yourself completely to Buddhist practice.” And it seems to me that he felt, where you could have pursued this career in science, and you could have made discoveries about things that were new, and instead you went back to something that had been around for thousands of years.

Mr. Ricard: Yeah, he thought that was a waste — I mean waste of potential. But what I really, really am grateful is that he didn’t show that. And so there was no slamming of doors when I left — both my boss, François Jacob, Nobel Prize — he didn’t understand either. [laughs] But when I saw him 25 years later, he kept on looking at me and saying, “Oh, you look good. You look good.” So — not too bad. [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: But I think what intrigues me is the line that was there for you, because I think, for you, it was less of a departure from your curiosity, your passion for discovery as a scientist. Here is something you wrote in another book which was a form of a dialogue, The Quantum and the Lotus, which I really loved. “Is there a solid reality behind appearances? What is the origin of the world of phenomena, the world that we see as ‘real’ all around us? What is the relationship between the animate and the inanimate, between the subject and the object? Do time, space, and the laws of nature really exist? Buddhist philosophers have been studying these questions for the last 2,500 years.”

Mr. Ricard: Yeah. I mean, for me, this idea — “Oh! How you can go from Pasteur Institute to the Himalayas? What a break” — there’s no break. I mean of course, you change rooms, you change clothes, you move from one place to another. But there’s a continuity in what you do, unless you are forced by a tragic, traumatic event, or you become mad. So in my case, I was very happy to get Pasteur Institute — I think that scientific training helped me a lot to have at least have some kind of rigorous mind. But then, that was it. To stay another few years, then I would have felt sort of like an animal caught in a trap. That was no more what I aspired to. And then, fortunately, I didn’t have to wait till I was retired, 62 or something, to start that. [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: Right. So, you know, Einstein felt that Buddhism was perhaps the religion of the future that could reconcile the best insights of science and spirituality.

Mr. Ricard: You know, it’s amazing — that quote of Einstein is typically Einstein’s style. But I could never, never trace it to a precise speech or something. But everyone agrees that it sounds very much like Einstein’s writing or speech.

Mr. Tippett: Yeah, I haven’t heard it so much as a quote as an idea, I mean more where his mind was going.

Mr. Ricard: It’s a beautiful quote, which really says that it’s the one that fits with the cosmological vision that can reconcile everything.

Ms. Tippett: That it can reconcile these things or hold them together in a creative tension. And then it really intrigues me, because I think that this Mind and Life Initiative of the Dalai Lama that you’re also a part of is a 21st-century manifestation of that idea. So talk about that.

Mr. Ricard: Yes. You see, the Dalai Lama himself has always been so interested in science. He says, “Possibly, had I not been Dalai Lama, I would have been an engineer.” He says when he sees tools, he has a hard time keeping his hands off. [laughs] He’s teasing. But from an early age, he was a very curious mind, very inquisitive mind. And so when he came in exile, one of his wishes was to meet with great scientists. He met with Karl Popper, with great quantum physicists, and then, more and more, with psychologists and neuroscientists. So when they saw that, some of them got the idea of creating that Mind and Life Institute — Francisco Varela, a great neuroscientist, Adam Engle, who is a former businessman, now the chairman of Mind and Life — to facilitate this dialogue.

First of all, it was just to bring them together and have these wonderful small-scale dialogues, five or six scientists, maybe 20 observers, and that was it. But then it quickly turned out that the discussion was so lively, so enriching from both sides. They were not just coaching the Dalai Lama, they were also learning a lot from his kind of mind. And that — it became a little bit bigger. Some public events started to happen, like the first one at MIT. It was “Investigating the Mind.”

Ms. Tippett: When Jon Kabat-Zinn was involved in that.

Mr. Ricard: It was in 2003. It was quite groundbreaking. There were 1,000 scientists there and Nobel Prize-winners, and so forth, but also the idea of starting a research program, that because Buddhism considers itself as an empirical approach of the functioning of the mind, the mechanism of happiness and suffering, and so “empirical” means we can certainly work with scientists without any risk of feeling threatened by that, because if something is false, it’s false. What’s the problem with that? [laughs]

So in 2000, following one of the meetings that was devoted to destructive emotions, the first one myself, I participated — in Dharamsala for five days. And halfway through the week, His Holiness, one morning, with his typical commonsense approach said, “Well, all this is very nice, but what can we contribute to society?”

[music: “Reverence” by Songs of Water]

Ms. Tippett: Some of the scientists present at that exchange responded to the Dalai Lama’s challenge by creating a rigorous research program, using scientific protocol to investigate the tangible physiological effects of meditation. Some of the most highly influential studies have been done since by Richard Davidson at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Such research might one day yield new understanding of the mind, of the ultimate nature of human consciousness. But even the earliest experiments with serious long-term meditators began to change the field of neuroscience by providing original evidence that the human brain alters across the lifespan, a capacity known as neuroplasticity.

[music: “Reverence” by Songs of Water]

Ms. Tippett: You were one of those meditators often referred to as Olympic meditators, as you said, people who have meditated more than 10,000 hours or something.

Mr. Ricard: Yeah, I think I would calculate it roughly at 40,000, but probably most of them completely distracted, I don’t know. But I think, in numbers, I did that. But yes, because I was at that first meeting, and I was from both worlds, I volunteered, because I thought it was fun and I was very interested and curious.

Ms. Tippett: And this was with Richard Davidson.

Mr. Ricard: Richard Davidson. So I was the first guinea pig, let’s say. And then this program has taken strength. And now many labs, there’s at least five or six major laboratories in the United States and in Europe who are now doing very in-depth research, not only in long-term meditators but also — which is more probably relevant to our work — with short-term meditation, like eight weeks, 20 minutes a day, what change does that bring? And that also gives remarkable results.

Ms. Tippett: I’ve seen pictures of you hooked up to all the electrodes. It looks like some kind of alien headdress. [laughs] So OK, help me understand what’s been learned, at least part of what’s been learned, what surprised the scientists. As you say, it’s no surprise that there’s a physical correlate, that you’re meditating and that in that moment they might see something happening in your brain. But I think that one of the learnings that challenged some thinking was that these changes were permanent, right, that even when you weren’t meditating, the gamma waves were present and were different.

Mr. Ricard: Well, you see, first of all, I think it was very much needed to show that long-term or even short-term mind training — you spoke of neuroplasticity. What does that mean? Plasticity means the brain can change, functionally and possibly structurally, following a training. Actually, this is one of the major discoveries in neuroscience for the last 20 years, not only, at all, with meditation. Twenty years ago, it was thought that the adult brain can’t change anymore because it will make a huge mess so complex that you cannot fiddle around with that. Then they found that birds that learn new songs, the brain changed. Musicians that played 10,000 hours of violin, the area of the brain that has to do with the coordination of the fingers is vastly increased, that London cab drivers who have to learn 20,000 streets by heart, the area that is to do with topology is vastly increased.

So what about compassion? What about focused attention? Basically, it is just another skill. Of course, it’s a skill that matters more in your life. Compassion obviously matters more than learning 20,000 streets, except for taxi drivers — probably they need both. [laughs] But those are such basic human qualities that if you can cultivate them, you can imagine how crucial it is. And so to establish that meditation is not just like a nice relaxation where you empty your mind, those clichés that are still attached to the notion of meditation, that’s why we prefer, maybe, the idea of mind training, and to rest in the perfect transparency and the freshness of the present moment is not a strenuous exercise, but it is something that requires experience.

Now the question about the ultimate nature of consciousness, of course, that’s not what we are looking for right now. There’s no way I can — science right now could address that question except on the philosophical level. But if you want, we can go into detail about the Buddhist reasoning about why the nature of consciousness could be something else.

Ms. Tippett: Well, that’s what I’d like. I’d like to know how you think about it, and it’s clear that there’s one way that science can define it at this point. How do you explain what they found?

Mr. Ricard: You have what we call primary phenomena. Look at matter — you know, the famous question of Leibniz, “Why is there something rather than nothing?” “Well,” you say. “Well, there is something, whatever it is.” You just have to acknowledge that the phenomenal world is there.

Now consciousness — you can study it in different ways. What we basically call the third-person approach means looking from the outside, and the first-person approach, looking into your experience. So third-person approach is very clear. It’s what neuroscience does better and better, is whenever people think of emotions or just life, something happens in their brain, and you can describe that in increasingly sophisticated detail. And when someone sees red, or someone feels love, you could describe right down to the most single neurons what’s going on, if you had the power of investigation. But you have no clue what it means to see red, feel love, as an experience. So that’s the first-person. I mean a great neuroscientist told me, “There’s no mind, there’s just brain function.” OK, fine. Brain functions.

But we have experience. Nobody can deny that. And actually, that experience is primary to anything. There was no science without experience. We would not conceive of the brain without experience. Without experience, forget about the world. There is something very fundamental that is the basic cognitive quality of mind. You can call that basic awareness. You can call it a fundamental aspect of consciousness — the most basic quality that you know, rather than you don’t know, just like in matter, there’s something rather than nothing. In Buddhism, we call it the luminous aspect of mind — not that it shines light in the dark, but luminous because that’s what illuminates your world. It’s like a torchlight, a light that allows you to see things; but light is the fundamental thing that doesn’t change. If light shines on a heap of garbage, it doesn’t become dirty, it just reveals it. If light shines upon a diamond, it doesn’t become expensive, it just reveals the diamond. So there’s a fundamental component that is basic consciousness. So now you can say that from that perspective that this is also a primary phenomenon. So that’s the Buddhist reasoning. It corresponds to experience and is just an open possibility for investigation.

[music: “Tides In Their Grave” by Talkdemonic]

Ms. Tippett: You can listen again and share this conversation with Matthieu Ricard through our website, onbeing.org. I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[music: “Tides In Their Grave” by Talkdemonic]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, I’m with the Tibetan Buddhist spiritual teacher, Matthieu Ricard. I sat down with him in Vancouver, Canada at a series of gatherings with the Dalai Lama, scientists, educators, and activists.

Matthieu Ricard is the author of bestselling books on happiness, contemplation, and altruism. His book The Quantum and the Lotus is a conversation between him and the astrophysicist Trinh Xuan Thuan. Thuan was born Buddhist in Vietnam and became a scientist. Ricard grew up in a secular family in France, trained as a scientist, and became a Tibetan Buddhist monk. Both are intrigued by correlations they trace between the way quantum physicists describe matter and energy and the way Buddhists understand the interdependence and impermanence of human experience and all of life.

Ms. Tippett: You have this book, The Quantum and The Lotus, which is a dialogue between you and an astrophysicist, Trinh Xuan Thuan. And I wonder, I’d love to know about what insights emerged for you in that conversation, what you — and I know that you are schooled in all of this, you read this anyway. But talk to me a little bit about what you’ve learned, in that conversation and in others, about how some of these very fascinating ways that the insights of modern physics are bearing out some of the things or giving a new way to think about some of the things that Buddhists have been saying and practicing for many millennia.

Mr. Ricard: So it was another great encounter. I met Trinh Xuan Thuan in Andorra, in the Pyrenees. We were both invited to some summer university. And immediately, he said, “I’m born in Vietnam, born a Buddhist. I always wanted to have a dialogue about Buddhism and astrophysics, or modern science.” We did that. It was wonderful. The most fascinating thing I learned through this dialogue was precisely about something very deep about the nature of reality, related to interdependence and impermanence. And interdependence, of course, in modern physics is slightly different. There’s non-localization, the fact that if one photon or particle split into two, and they shoot out at basically any distance in the universe, they still remain part of a whole. So there is something there that is still not separate. So that was an incredible insight for me, because interdependence is not just the fact that things are related but also that, therefore, they are devoid of a totally autonomous, independent existence.

Anything — beautiful, ugly, I don’t know, red, blue — any characteristic comes to relation. Relations co-define an object. Like take a rainbow in the sky. Well, it looks very beautiful, very, very vivid and clear. You would think that that rainbow is something existing on its own. Now behind you, you mask the rays of sun, and there is not a speck of existence of that rainbow that remains. It’s all gone, because you remove something, an element of a set of relations that crystallize that rainbow somehow as a phenomenon. The idea is the same for every single phenomenon — nothing exists on its own. And that has profound repercussions in Buddhism, not only as a philosophical idea but also the way we grasp to the world. If you grasp to something as being “mine,” therefore, that object exists on its own.

Ms. Tippett: And I mean would you also say that a human analogy would be this phenomenon of globalization?

Mr. Ricard: Well, and at least to what the Dalai Lama calls the “sense of universal responsibility.” I know more and more leaders are speaking of interdependence, and I hear that word again and again about “the world is interdependent.” And it is true. We are interdependent, even, I would say, even more deeply than what we mostly think. But that leads to, also, the sense of — interdependency is at the root of altruism and compassion.

That’s one of the consequences of understanding interdependence. If you think of separate entities, well, I am a separate entity, as well. So what do I do? I create a small bubble, a self-centered bubble, and I take care of my own happiness, because after all, I’m this separate entity, so I just have to build my own happiness. And that’s fine, and everyone will become happy in their own bubble, and then the world will be fine.

Well, if it would work, OK, but this is not working. Why? Not just because of moral issues, because it’s bad to be self-centered — because it’s dysfunctional, because it’s at odds with reality. So it doesn’t work.

Ms. Tippett: Right. I want to talk about happiness. You’ve been labeled “the happiest man in the world,” coming out of these Davidson experiments. [laughs]

Mr. Ricard: Totally, totally artificial. [laughs] I issued about 1,000 disclaimers, but nobody cares.

Ms. Tippett: You did? [laughs] They didn’t get covered. I did identify with some of the things that you’ve written — that when you were younger, you thought that happiness was not necessarily a very laudable goal.

Mr. Ricard: Well, I just had no idea about it, basically.

Ms. Tippett: Right, but it — you’re worldly-wise and rational, and we also live in this culture where the word “happiness” gets completely watered down. And so I want to just talk about how you define happiness, because we have to put a lot of preconceptions aside.

Mr. Ricard: Yeah, it is very important, because that’s why, also, this word is so vague.

Ms. Tippett: Yeah, it’s a problem.

Mr. Ricard: That you can use it — “buy this toothpaste, and you’ll be happy” and — OK, good luck. So I think we should clearly see what are the inner conditions that foster a genuine sense of flourishing, of fulfillment, that the quality of every instant of your life has a certain quality that you appreciate fully. So you see, it’s very different from — people sometimes imagine that constant happiness will be a kind of euphoria or endless succession of pleasant experiences. But that’s more like a recipe for exhaustion than happiness.

Ms. Tippett: [laughs] Right.

Mr. Ricard: And also, if you look at the parameters, this is very different. Pleasure depends very much on circumstances, what triggers it. Then it’s a sensation, in a way. So sensations change from pleasurable to neutral and to unpleasurable. I mean even the most pleasurable thing — you eat something very delicious. Once, it’s delicious. Two, three times, OK. And then ten times, you get nauseous. You are very cold and shivering. You come near a bonfire, such a delight. But then, after a few minutes, you start — OK, then you move back. It’s too hot. The most beautiful music, you hear it five times, 24 hours, it’s a nightmare. And also, it’s something that basically doesn’t radiate to others. You can experience pleasure at the cost of others’ suffering. So it’s very vulnerable to the change of outer circumstances. It doesn’t help you to face the outer circumstances better.

Now if we think of happiness as a way of being, a way of being that gives you the resources to deal with the ups and downs of life, that pervades all the emotional states, including sadness. If we think of sadness as incompatible with pleasure, but it’s compatible with what? With altruism, with inner strength, with inner freedom, with sense of direction and meaning in life — those aren’t sad things. But if you don’t fall in despair, still you maintain that wholeness and that sense of purpose and meaning.

Ms. Tippett: So happiness also, the way you describe it, it’s something that can encompass sadness and grief.

Mr. Ricard: Can what?

Ms. Tippett: Encompass, contain these things.

Mr. Ricard: Encompass every mental state except those who are just opposite, which is like despair, hatred, precisely the mental factors that will destroy inner peace, inner strength, inner freedom. If you are under the grip of hatred, you are not free. You are the slave of your own thoughts. So that’s not freedom. Therefore, this is opposite to genuine flourishing and happiness. So we have to distinguish mental factors which contribute to that way of being, the cluster of qualities like altruistic love, inner freedom, and so forth from those who undermine that, which is like jealousy, obsessive desire, hatred, arrogance. We call that “mental toxins,” because they poison our happiness and also make us relate to others in a poisonous way. So that’s something that you can cultivate, unlike pleasure. You don’t cultivate pleasure, but happiness in that sense is a skill. Because why? Because altruistic love can be developed. We have the potential for it, but it’s really untapped. All these other qualities can be enhanced to a more optimal way, and therefore, those are skills.

Ms. Tippett: All right, you’ve also talked about this kind of happiness as a way of interpreting the world — you said “a way of being.” And then you quoted Tagore. I thought this was such a wonderful illustration. “We read the world wrong and say that it deceives us.”

Mr. Ricard: Exactly.

Ms. Tippett: It’s how do we read the world?

Mr. Ricard: It’s the same situation. People express it many different ways. We know that. So the quality of our experience can easily eclipse the other conditions. Not that the other conditions don’t matter — don’t mistake for that. I mean it’s infinitely desirable that we provide to others, and to ourselves, conditions for survival. There are so many people in this world that cannot feed their kids. It’s unacceptable. So anything that can be done should be done, and it’s a joke if we don’t do it. I mean we are failing all principles of basic morality.

But yet, we should acknowledge at the same time that you can be miserable in a little paradise, have everything, so-called, to be happy, and be totally depressed and a wreck within. And you can maintain this kind of joy of being alive and sense of compassion even in the worst possible scenario, because the way you translate that into happiness or misery, that’s the mind who does that. And the mind is that which experiences everything, from morning till evening. That’s your mind that translates the outer circumstances either into a sense of happiness, strength of mind, inner freedom or enslavement. So your mind can be your best friend, also your worst enemy, and it’s the spoiled brat of the mind needs to be taken care of, which we don’t do. We vastly underestimate the power of transformation of mind and its importance in determining the quality of every instant of our life.

Ms. Tippett: So I imagine that people ask you, “How do I become happy?” What do you say? How do you respond to that?

Mr. Ricard: Well, clearly, by first saying yes, outward circumstances are important, I should do whatever I can. But I should certainly see that at the root of all that, there are inner circumstances, inner conditions. What are they? Well, just look at you. Now if I say, “OK, come, we’ll spend a weekend cultivating jealousy,” now who is going to go for that? We all know that, even say, “Well, that’s part of human nature,” but we are not interested in cultivating more jealousy, neither for hatred, neither for arrogance. So those will be much better off if they were not — didn’t have such a grip on our mind. So there are ways to counteract those, to dissolve those. I mean you cannot, in the same moment of thought, wish to do something good to someone or to harm that person. So those are mutually incompatible, like hot and cold water. So the more you will bring benevolence in your mind at every of those moments, there’s no space for hatred.

That’s just very simple, but we don’t do that. We do exercise every morning, 20 minutes, to be fit. We don’t sit for 20 minutes to cultivate compassion. If we were to do so, our mind will change, our brain will change. What we are will change. So those are skills. They need to be, first, identified, then, cultivated. What is good to learn chess? Well, you have to practice and all that. In the same way, we all have thoughts of altruistic love. Who doesn’t have that? But they come and go. We don’t cultivate them. Do you learn to piano by playing 20 seconds every two weeks? This doesn’t work. So why, by what kind of mystery, some of the most important qualities of human beings will be optimal just because you wish so? Doesn’t make any sense.

I have a friend who is 63 years old. He used to be a runner when he was young. He gave up running. Now a few years ago, he started again. He said, “When I started again, I could not run more than five minutes without panting for breath.” Now last week, he ran the Montreal Marathon at 63. He had the potential, but it was useless until he actualized it. So the same potential we have for mind training, but if we don’t do anything, it’s not going to happen because we wish so.

Ms. Tippett: What you are talking about is a life discipline, and it has to do with the everyday, as well.

Mr. Ricard: Well, I mean myself, I was struck by that, that we need to put that in action, in a way. “Action” doesn’t mean frantically running around all day long — which I have unfortunately been doing a bit too much — but exemplifying that in our life. So that’s what led me — my only regret, some years ago, was not to have hands on, trying to serve others. So when I had the possibility of doing that, I jumped into that, and I’m absolutely grateful and delighted that I can. Now we have — we treat 100,000 patients in the Himalayas, India, Tibet, and Nepal. We have 15 kids in the school that we built. It’s not huge, compared to some other big organizations, but at least we did our best. So my motto, in a way, will be to transform yourself to better serve others.

If you see the humanity in the world, grains of sand that bring everything to a halt, it’s corruption, clashes of egos — human factors more than resources. So how to avoid that? There is a lack of human maturity. So it’s not a vain or futile exercise to perfect yourself to some extent before you serve others. Otherwise, it’s like cutting the wheat when it’s still green, and nobody is fed by that. So we need a minimum of readiness to efficiently and wisely be at the service of others. So compassion needs also to be enlightened by wisdom. Otherwise, it’s blind.

[music: “She’s Only Sleeping” by Songs of Water]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, I’m with the biologist turned Tibetan Buddhist monk and spiritual teacher, Matthieu Ricard. I sat down with him at a conference in Vancouver headlined by the Dalai Lama.

[music: “She’s Only Sleeping” by Songs of Water]

Ms. Tippett: This gathering that we’re at — and I think you find yourself in many gatherings like this, where there’s a collection of wise people, people who are practicing these things and finding an integrity. And here — the Dalai Lama was here, there were a number of Nobel Peace Prize-winners. And several people have said, and I hear this, also, in conversations I have, that we might be on the cusp of some kind of spiritual evolution, that people may in fact, human beings may in fact be learning something. And I think the fact that science is taking these spiritual disciplines, these spiritual technologies like meditation more seriously, are one manifestation of that. And yet, we will go back to the places we live in, and there’s also outside gatherings like this — we’re then confronted again with a great deal that’s wrong in the world. And I don’t — I wonder what your perspective is on where we are as a species, as a planet right now.

Mr. Ricard: I think ideas change slowly, but sometimes there are tipping points. For instance, the environment — I don’t know, 35 years ago or 40 years ago, when Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring, came out, and I was a teenager, a bird-watcher, and for us, it was a revelation. But we were just these kind of lovers of nature, and nobody cared for that, and they thought it was just crazy ideas. Now it’s a major preoccupation. It took a certain number of years, but it was all there already. So ideas like we should work towards a more altruistic and compassionate society is taking momentum, because also, now, it’s not more a luxury. It becomes a necessity.

So what is an evolution pressure is when it’s sort of necessary for survival. So in ancient times, it may be fine for tribes to fight each other over hunting grounds or whatever. Nowadays, with precisely this interdependence and this globality, we are all part of one family. That’s not just a nice, naïve image. Either we are all losers or all winners, in terms of survival. Now we can’t say that it makes sense for just one nation to be powerful, rich, and so forth. If the whole world is starving, that will create immense wars and difficulties. And the environment can only be a transnational solution. So hopefully evolution will take hold quickly enough so that altruistic behavior becomes — and not just seemingly altruistic behavior, which is selfishness in disguise, but real concern for all, because after all, the true altruism is a genuine consideration for all sentient beings, whether they are your tribe, your relatives, or your own gene lines — forget about that. It has now to be concerned for all that lives.

Ms. Tippett: Something that I see as a characteristic of you — OK, so you’ve issued disclaimers that you’re not the happiest man alive.

Mr. Ricard: I just want to say that it’s just taken by English newspapers. It’s not based on scientific data. I apologize to my scientist friends. It is better than to be labeled the most unhappy person in the world, fine. But it rests on no scientific evidence.

Ms. Tippett: OK. But let me just say this — a quality of you and of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and other very wise people I’ve come across, spiritual people, serious people, is also a very robust sense of humor. He’s always laughing. He’s funny. And even before I met you, when I’ve seen pictures of you, you always have a smile on your face. And I want to know, where does humor come into this, to wisdom?

Mr. Ricard: Well, humor comes with — when you are not — first of all, if the ego is not such a target that is always there, exposed to all the arrows of praise and blame and criticism and all that, and you are not too much susceptible to that, basically, you don’t care, to start with. Nothing to lose, nothing to gain from all this noise of “Oh, you are such a great guy” or “You are just a bastard” — what does it mean? It’s like egos. It doesn’t care. So it gives a sense of less vulnerability. It’s a real strength. People think that a strong ego is a strength. Strong ego is ultimate vulnerability. You are so preoccupied with that strong ego, you can’t sleep anymore. [laughs] But if this ego is transparent — “So? Fine.” So a sort of lightness.

And then, also, because you have this real confidence, not coming from strong ego, you are much more available to others, so — open to the world. I see that in Tibet very often. Sometimes, you find a very difficult situation. Our car, when we do those projects at schools and clinics, we get stuck in the middle of a river with our car. A big stream, it’s raining, everybody will just — you can imagine some people screaming, upset. Usually, it ends up everyone is on top of the car, cracking into laughter. Such — they think it’s such a funny thing. [laughs] So there’s a kind of — we do our best, and things happen, and why should you take it too seriously, because we will survive that, hopefully, and after all, what’s the problem? It’s just one part of the journey, and it’s so much more fun if you take it like that than making all these tantrums about things. It’s just precisely what we were mentioning before, the way you interpret the world.

I gave this example, which struck me. I was sitting outside our monastery once, and it was monsoon time in Nepal, a lot of mud and water. And we had put some bricks over about 20 to 30 meters, to go from one brick to the other to cross that mess. And one person came, a foreigner, and that person was just screaming, “How disgusting, this place!” And I was sitting there, and she’s going to scold me for it. [laughs] And then, so OK, then five minutes later, another person came, two ladies. And she was just hopping from one to the other, saying, “Oh, it’s so nice. It’s such fun. And when there is rain, there’s no dust.” And she was in exactly the same situation, and she had a sense of lightness and humor. The other one was just grumbling like crazy about it. So — same situation, different perspective.

Ms. Tippett: All right. That’s your last word. Thank you so much.

Mr. Ricard: Thank you.

[music: “Desert Sky” by Tuatara]

Ms. Tippett: Matthieu Ricard is founder of the humanitarian organization Karuna-Shechen, and he is the French interpreter for His Holiness the Dalai Lama. His books include: Happiness: A Guide to Developing Life’s Most Important Skill and Altruism: The Power of Compassion to Change Yourself and the World. His latest book is A Plea for the Animals: The Moral, Philosophical, and Evolutionary Imperative to Treat All Beings with Compassion.

Staff: On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Maia Tarrell, Marie Sambilay, Bethanie Mann, Selena Carlson, Carolyn Friedhoff, and Katherine Kwong.

[music: “Desert Sky” by Tuatara]

Ms. Tippett: Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoe Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing our final credits in each show is hip-hop artist Lizzo.

On Being was created at American Public Media. Our funding partners include:

The John Templeton Foundation.

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, working to create a future where universal spiritual values form the foundation of how we care for our common home.

The Henry Luce Foundation, in support of Public Theology Reimagined.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.