Resmaa Menakem

“Notice the Rage; Notice the Silence”

Across the past year, and now as the murder trial of Derek Chauvin unfolds with Minneapolis in fresh pain and turmoil, we return again to the grounding insights of Resmaa Menakem. He is a Minneapolis-based therapist and trauma specialist who activates the wisdom of elders, and very new science, about how all of us carry in our bodies the history and traumas behind everything we collapse into the word “race.” We offer up his intelligence on changing ourselves at a cellular level — practices towards the transformed reality most of us long to inhabit.

Image by Nancy Musinguzi/Nancy Musinguzi, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

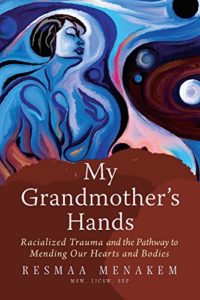

Resmaa Menakem (MSW, LICSW, SEP) teaches workshops on Cultural Somatics for audiences of African Americans, European Americans, and police officers. He is also a therapist in private practice, and a senior fellow at The Meadows. His New York Times best-selling book is My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: Across the past year, and now as the murder trial of Derek Chauvin unfolds, with Minneapolis in fresh pain and turmoil, I return again and again to the grounding insights of Resmaa Menakem. He is a Minneapolis-based therapist and trauma specialist who activates the wisdom of elders, and very new science, about how all of us carry in our bodies the history and traumas behind everything we collapse into the word “race.” We offer up Resmaa’s intelligence anew on changing ourselves at a cellular level — practices towards the transformed reality I believe most of us long to inhabit.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Menakem: So one of the things about the animal part of the body is that even though me and you are in this room, this nice place, there’s a part of the body that’s saying, “Yeah, but what else is gonna happen?” Even though you know nothing’s behind you, letting the body know it actually helps some pieces.

Now, if you get reps in with that — not just do it one time or just when I tell you to — what you may notice is that you have a little bit more room for other — literally, for other things to happen that can’t happen when the constriction is like that.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Resmaa Menakem has worked with U.S. military contractors in Afghanistan, as well as American communities and police forces. His New York Times best-selling book, part narrative, part workbook, is My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. I sat across from him in our studio in Minneapolis right before lockdown, in February, 2020.

I am curious — I’ve read you and listened to you — I’m always curious what people’s passion and calling become. And it feels to me like it’s right here in the title of the book — your grandmother’s hands.

Menakem: That’s it. That’s it. My grandmother, the women in my family — I have this sense — so when the idea of humanness came about, the first representation of that was the Black woman. Now, I’m not fighting nobody about that. That is, for me, where it starts. And so my grandmother and my mother and the Black women in my life have always been that protector and that nurturer and that person that would get at your butt and say, “Yeah, you can do it, and let’s keep moving” — and my wife. And so for me, my grandmother, and the story I talk about with her hands, is that piece around creation and emergence even in the midst of anguish and horror.

Tippett: So describe her hands.

Menakem: So my grandmother — my grandmother was not a very big woman. I would — [laughs] this is gonna be funny — I would say, skinny-stout woman. She was stout, but she was not a big woman. And she would hum, and all of this different type of stuff. My grandmother used to always shake her hand and complain of arthritis, and so she used to lay on the couch. So we would be watching the Bucks game or something like that — my grandmother loved the Milwaukee Bucks. So we would be sitting there, and then she would drape her legs across our lap, and then her hand would rest on her thigh, and she would turn the other way and be watching TV. And so we would just rub her hands.

And I can’t remember the exact age of what I was, but I was rubbing her hands one day, and I was comparing her hands to my hands. And so I’m rubbing them and I’m rubbing them, and I go, “Grandma” — and this was a half-joking — I had the tonal quality in my voice that was a half-joke there. And I said, “Grandma, why your hands so fat?” — like that, as I’m rubbing her hands. And without missing a beat — my grandmother didn’t even look at me — she goes, “Oh, boy, that’s from picking cotton.”

And I sat there. And I’m like, “From picking cotton?” And she must’ve picked up the tone, and she looked at me and saw me, and she goes, “Boy, you ever seen a cotton plant?” And that’s the quality that was in her throat. And I’m like, “No.” She takes her other hand, and she does her hands like this. She goes, “Them damn cotton plants got a burr in ‘em. They got burrs in ‘em like that.” And she goes, “I started walking up and down them rows when I was four years old.” And she said, “As you walking up and down the rows, you put your hands in, them cotton plants rip your hands up. And so when they rip your hands up, your hands bleed.” And this is the tonal quality she’s having in her throat. Now, I don’t know what that is, but I know it’s something I need to pay attention to. And so I’m looking at her —

Tippett: So you’re feeling what’s going on in her body, as much as the words she’s saying.

Menakem: That’s right. That’s right. Right there. That’s the energy. Einstein said energy cannot be created nor destroyed. But it can be thwarted. It can be manipulated. It can be moved around.

When we’re talking about trauma, when we’re talking about historical trauma, intergenerational trauma, persistent institutional trauma — and personal traumas, whether that be childhood, adolescence, or adulthood — those things, when they are left constricted, you begin to be shaped around the constriction. And it is wordless. Time decontextualizes trauma. So when my grandmother is saying that, I need to pay attention to that. And for her, it’s decontextualized, so she doesn’t even have a context for it.

And so as she’s saying that, I said, “Oh.” And then she said, “Yeah.” And then she turned back and started watching TV again.

And so those types of things is what started — I’ve always thought about this type of stuff. But there were pretty seminal things that happened in my life that made it so I was able to actually sit down and write it and put things in place.

And here’s the interesting thing about the book, is that I believe — like when bodies of culture come up to me and talk to me — if a Black woman or Indigenous woman or somebody comes up to me and talks to me, the one thing that they all say is, “I been thinking this my whole life, and then, when I read it in your book, it made me feel like I wasn’t crazy” — because racialization makes us walk around like we’re crazy — like the things that are vibratorially happening to us, the images that are happening, the meaning, all of that different type, the fact that we walk around with this bracedness — because we’re infected by this idea that the white body is the supreme standard.

And I’ve done workshops where I’ve said — just said to the people in there, the bodies of culture — I’ve looked at them, and I say, “You are not defective.” Just saying that, tears start to well up in people’s faces.

Tippett: I feel like — one way I’ve thought about this time we’re living in — I was born in 1960. So I feel like those of us who lived through the ’60s — although I was a child, but still, it’s in my body, too — there was a lot of progress. It felt like a lot of progress was made. A lot of new laws were passed that were revolutionary, in their way. And certainly, it’s true in many areas, including with gender, with the relationships between men and women, but it’s absolutely true around race. And I felt like we changed the laws, but we didn’t change ourselves.

And to me, what you speak into that, very concretely — you say, “We tried to teach our brains to think better about race” — which makes sense; it felt like that was a good idea. But it didn’t take us — we tried to work on it in terms of ideology and public policy and politics.

But you have this radical statement that “While we see anger and violence in the streets of our country, the real battlefield is inside our bodies” — in all of our — I mean, I’m saying this — all of our bodies, of every color. You say, “If we are to survive as a country, it is inside our bodies where this conflict needs to be resolved”; that “the vital force [behind] white supremacy is in our nervous systems.”

Menakem: Just watching you say that, this is why I talk the way that I talk. So let me start with just a definition, first. So the premise of the work is predicated on the idea that there was a certain time where the white body became the supreme standard by which all bodies’ humanity shall be measured. If you don’t understand that, everything about America will confuse you. Everything about racialization will confuse you.

So I have white people that call me, contact me, want me to come and do some consulting with them, stuff like that. And one of the things I’m always clear about is that if you can’t say the term “white body supremacy” —

Tippett: But you’re nuancing the term in a really useful way, and a way that is rooted in —

Menakem: I’m operationalizing it. The white body is used to hearing things that make it comfortable. And so when you say something like “white supremacy” — especially here in Minnesota — everybody goes, “Yes, absolutely. Yeah, yeah, absolutely.” And then what happens is, it goes — just the term, “white supremacy,” is a very intellectual term. It doesn’t land in the body.

Tippett: No, because also, as you point out, most people think, “But that’s not me.”

Menakem: “That’s not me.”

Tippett: “Yes, I want to talk about it, but you’re not talking about me. I’m a good person.”

Menakem: “You’re talking about them. You’re talking about my mean uncle.”

Let me give you one quick example. Recently, I got asked to come and talk to like 300 people who were DEI.

Tippett: And we should say: diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Menakem: Diversity, equity, and inclusion. And even when you say it, everybody kind of like, their eyes get dreamy. It’s like, “Oh, diversity, equity, inclusion.” But if you don’t define what that means, it can mean “Taco Tuesday.” It can mean “Collard Green Wednesday.” It can be anything that’s kind of cursory. So one of the questions that I asked, when I went to this thing and they asked me to come — “Yes, we really want you to be here, and —” that was my white voice — “We really want you to come here and do this thing …” [laughs]

Tippett: [laughs] Thank you.

Menakem: [laughs] So what happened was, I asked one question. I said, “How many people in here believe in diversity?” Everybody shot their hands up. Boom. Everybody. I said, “Answer this one next question.” And I said, “Don’t bring your hands down. Answer this question. Diverse from what?”

Tippett: [laughs] Right.

Menakem: Because when you say “diversity,” that means you start someplace first, and then you diversify from it.

Tippett: I know. I know.

Menakem: Hands start coming down, because we all know it, intrinsically. But if you don’t say it, then it’s not operational. And white comfort trumps my liberation. Even bodies of culture genuflect to white comfort, because we know, when white people get nervous, people lose their jobs. When white people get nervous, people get hung from trees. When white people get nervous, babies get put in cages.

Tippett: So I want to back up a little bit and talk about your particular way into this, with the focus on the trauma that is actually in all of us. And you’re working with realities that are as old as the human brain and body, but very new science. And so I’m curious about — so it’s the science of trauma — PTSD, everybody knows that now, but it’s just a couple decades old. The whole field of epigenetics, about how trauma and resilience can cross generations —

Menakem: I just read somewhere, it says 14 generations.

Tippett: So this is all new. As you say, it’s new information that lands like “Oh, of course, we knew that all along.”

Menakem: It’s always been there. There’s always been this kind of resonant knowing that something’s there. Because it’s been decontextualized and handed down from my mom, my grandmother, my grandfather, blah blah blah, all the way down, I didn’t have a language for it, but there was a knowing that “this ain’t right.”

Tippett: That they’d lived through a lot of trauma.

Menakem: Not just that they lived through trauma, but that the angst and the anguish was decontextualized. And so for my Black body to be born into a society by which the white body is the standard is, in and of itself, traumatizing. If my mom is born as a Black woman, into a society that predicates her body as deviant, the amount of cortisol that is in her nervous system when I’m being born is teaching my nervous system something. Trauma decontextualized in a person looks like personality. Trauma decontextualized in a family looks like family traits. Trauma in a people looks like culture.

[music: “The Process of Leaving” by E*Vax]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today with clinical therapist and trauma specialist Resmaa Menakem.

[music: “The Process of Leaving” by E*Vax]

So another radical, radical insight that you have, again driving back to a core truth, is that the trauma in Black bodies is born not just of white bodies and white people, but with the history of trauma that white people have inflicted on themselves and each other.

Menakem: That’s the piece. That’s the piece.

Tippett: It’s such a revelation, to join those dots.

Menakem: So the idea that people could go through a thousand years of the Dark Ages and come out of that unscathed — 500 A.D. to 1500 is when we’re talking about, when we say the Dark Ages. So you mean to tell me that the level of brutalization —

Tippett: And the Middle Ages — medieval torture chambers, which is another — those are two words that follow.

Menakem: Exactly. Flaying, whipping — here’s the thing. Land theft, enslavement, imperialism, colonialism, genocide — all of that.

Tippett: The Tower of London that we go to as a tourist attraction, and it’s one torture contraption after the other.

Menakem: Plagues — [laughs] all of this stuff happened for a thousand years, and then that body came here. This is why I say, white people, don’t look for a Black guru. Don’t look for an Indigenous guru. Find other white people, and start creating a container by which you can begin to work race specifically — not race in this and race in that and race in this, and bake bread together and do all that — not that, not a book club. You specifically deal with the embodiment of race and the energy that’s stored with that.

Listen. Let me say this. The Middle and the Dark Ages set the table for poor white people because they had been brutalized by powerful white people. It set the table that when powerful white people in the 1600s came — here in America, came to poor white people —

Tippett: And we know the narrative — they fled. They fled. We never think, these were traumatized people.

Menakem: So the other thing that I say is that when people talk about the 13 colonies, the 13 colonies were filled with colonized white people. So what ends up happening is that when you have that level of brutality for all that time, and then right after the Bacon Rebellion is the first time you start to see, in law, “white” persons — not landowners, not merchants, “white” persons …

Tippett: That language.

Menakem: … at that moment, the white body became the standard of humanity — not merchants, not landowners, the white body, because at that moment, the white body had dominion over, and everything else was a deviant from that. And then a couple years later is when you start to see white persons show up in Virginia law.

By the time they offered that to poor white people and said, “Ey, you want to be white?” — after all of that brutality, white people said, “You mean all I gotta do is be white, and my babies may not have to go through that? Yeah, I’ll take that. Let’s take that.” And that’s what sewed it in. So now they saw their allegiance more with white landowners than the enslaved Africans that they were rebelling with.

Tippett: You’re also saying that it was actually a way of co-opting poor white people into their further traumatization.

Menakem: That’s exactly right. That’s why what you see now is like the flower of the seed of that. That’s what you’re seeing right now. And so when you say little things, the body hears, “Yeah, that’s right. They ain’t human.”

Tippett: Well, one thing that you say — that there’s a lot of problems with the way progressives approach all this, well-meaningly, and one of them is that rather than creating culture, they create strategy — which, again, is a head move; it’s a cognitive move.

Menakem: That’s exactly right.

Tippett: But what they — the people that are not ready to reckon with this, for all these many reasons — create instead is culture: symbols, stories, music, and belonging, and that that’s so much more powerful than a strategy.

Menakem: Exactly right. So if I’m a 13-year-old white boy, and I get on the internet, and I see symbol, I see rules of admonishment, rules of acceptance, a tone, a cadence, a dress, an understanding, a rhythm — so I’m not just talking about just the things that we see, the dress and stuff like that. I’m talking about the glue — the resonant and dissonant glue that holds things together.

Tippett: And it’s about your identity. It’s not even necessarily about actions you’re gonna perpetrate against other people. It’s about how you feel inside your body.

Menakem: It’s about how — and this is why I keep coming back to energy. And I’m not talking about mystical energy, I’m talking about how this stuff — and so one of the things that happens is: I’m a 13-year-old white boy. I’m lost. But I’m watching this, and they have a whole history, even if I know that the history is bunk. But it has a beginning, a middle, and an end. And we all like a good story. I’m 13; I’m lost; I’m poor. And the reason why I’m poor is because these little Mexicans keep coming over here, taking my job. The reason why I’m poor is because these Black brutes that the only thing that they can do is jump and play football, or sing and dance — they’re taking my job, and I’m the rightful heir.

[music: “Amor Porteño” by Gotan Project]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Resmaa Menakem.

[music: “Amor Porteño” by Gotan Project]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today with trauma specialist Resmaa Menakem. His book My Grandmother’s Hands is a completely original contribution — part narrative, part workbook — of old wisdom and very new science around healing racial trauma in our bodies. I sat across from him in Minneapolis, where we both live and work, just before lockdown.

Well, I mean, I think it’s time to talk about the vagus nerve. [laughs] So what I want you to help explore — you don’t have to just talk about the vagus nerve, but I feel like this is another piece of knowledge about ourselves. And I think the way you apply what we’re learning with this to this particular reckoning — this moment of our possibility of becoming more fully human — is really, really revealing.

Menakem: So the vagal nerve is very important. So I’m gonna ask you a question, Krista. Have you ever been on the phone with somebody that you love — parent, partner, husband, child — and they’re talking to you, and all of a sudden, you go, “What’s wrong?” Have you ever had that happen? And you don’t even know — they haven’t said anything, they ain’t sounding particularly sad, but you go, “huh” — 3,000 miles away, and I’m picking up on something.

And one of the things that I talk to people about is that there is this nerve that comes out of the brain stem, and it’s called the wandering nerve. And it hits in the face, it hits in the pharynx, it hits in the chest, it hits in the gut — it wanders the whole body. And it, I believe, is one of the things why we have “gut” reactions, because most of that nerve actually ends up in the gut. And when we’re stressed, that gut constricts or opens. And so one of the things that happens is that if I’m with you long enough, like if me and you become friends, over time I will start to hear things in your throat because the vagal nerve is either open or constricted.

Tippett: That’s that constriction that you heard in your grandmother’s voice when she told you about picking cotton.

Menakem: Exactly right. I needed to pay attention to that, even if I didn’t know what it was. And so it shows up in the eyes, it shows up in the mouth — this is why, when we’re tracking each other, we pick up on things, and even if we don’t know what it is, we know — “that was something.”

Tippett: But as you say, it also just shows up in the — to me, the voice carries the body, because I talk to people a lot about how to have a different kind of conversation, but one thing I’ll say, which you just confirmed for me and helped me understand better, is so many things pass between us at an animal level, before any words are spoken or before the first sentence is complete. You can’t fake — you can pretend to be curious; you can ask a curious question — if you’re not actually curious, the other person will respond appropriately.

Menakem: That’s right. That’s the authenticity piece. We’re hardwired to try and pick up on what’s authentic or not. Now, bodies of culture that land in this culture have to pick that up before we even come on the planet.

Tippett: Right, bodies of color.

Menakem: Well, I don’t say “bodies of color” anymore, because what I’m trying to do is, I’m trying to reclaim the idea that I’m actually a human.

Tippett: So you’re saying that you’re formed by the culture, physically —

Menakem: Bodies of culture. That’s right. And so one of the things that happens with the vagal nerve — there’s two. There’s the vagal nerve — I call that the soul nerve — and then there’s a muscle, the psoas muscle. That psoas is a beast, because the psoas, what it does is, it connects the top part of the body with the bottom part of the body. It also — if you’re braced, it also manages whether or not you mobilize or immobilize. And if you’re born to people who are already braced, you pick up in your psoas this kind of locking down, this kind of bracing, decontextualized.

And so what I’ve been talking to people about is, how do we begin to get the reps in with those pieces? So you’re gonna need time to condition your body to be able to deal with the aches, deal with the doubt, deal with all of that difficulty. You’re gonna have to get up against your own suffering’s edge, before the transformation happens. But you need to condition that. Why do we think that when we talk about race, that’s any different — for me to say, “We’re gonna have a white body supremacy talk; deal with the root of this stuff”?

Tippett: Well, you can’t drop that on people, either, because they won’t be ready to — they’ll also brace.

Menakem: But let me say this. So you just did something I think is very important.

Tippett: If anybody could see me, I physically, like …

Menakem: You braced. You were like, “No.” Your face turned red — the whole thing, just like, “No.”

But, you see, that’s where you start — right there, not in this “let’s bring everyone in and make them all comfortable.”

Bodies of culture are uncomfortable every day. White people have the luxury of not being so. And what I’m saying is that that idea that — just what you did, that piece right there — that’s where you have to start, and white people have to start with that, because — I say this all the time. Whenever I do these things, inevitably, I have some white woman that comes up to me afterwards and starts crying. White tears, white women’s tears, can move a nation. They will move people to mobilize. An Indigenous woman’s tears ain’t gonna move nothing. A Black woman’s tears ain’t gonna move nothing. And so the piece that I said about that is that this idea of being able to land this race question in a way where white people are uncomfortable is a fallacy. It’s performance art.

Tippett: So you really do say, let the bracing begin, and then start healing it there.

Menakem: Right there. Right there. That’s the only — right there.

Tippett: So that’s what all these exercises — there are so many, and they’re so much about just, oh, feeling at home in our bodies. Some of them are really basic things. They’re touch. They’re like, rubbing your grandmother’s hands, or the humming, even, which actually affects the vagal nerve. Some of these things about noticing — and one of the exercises you have for white people, white bodies, is putting yourself into situations with people of color and noticing what happens in your body and how you feel.

Menakem: Notice the rage. Notice the silence. Notice all of the stuff. And that’s the culture-building that I’m talking about. That’s the container-building.

Tippett: I want to read a passage you wrote.

Hey, are we — I feel like we’re so animated in here. OK? I was worried if the microphones are gonna be — if they can handle it.

OK, 36. Here, this is something — there are so many passages I could read, but this is —

Menakem: It’s so cool to watch you read this, because I’m tracking you as you’re reading it, and I’m getting this —

Tippett: [laughs] This is why I do my interviews remote. [laughs] I don’t have to worry about what my body is communicating. [laughs]

So this is one of the ways you summarize, in not very many words, how confusing and contradictory the ways are that, culturally, we hold our race and see others. So this is: “Because of white body supremacy, here is how white, Black, and police bodies” — because that’s how you talk about police bodies; and we’re not talking about that, but that’s a reason to read the book — “the white body sees itself as fragile and vulnerable, and it looks to police bodies for safety and protection. It sees Black bodies as dangerous and needing to be controlled; yet, also, as potential sources of service and comfort. The Black body sees the white body as privileged, controlling, and dangerous; it is conflicted about the police body, which it sees as sometimes a source of protection, sometimes a source of danger, and sometimes both at once. The police body sees Black bodies as often dangerous and disruptive, as well as superhumanly powerful and impervious to pain” — which is just scratching the surface of — just acknowledging what knots we’ve tied ourselves in, literally.

Menakem: Literally.

Tippett: Our nervous systems are in knots.

Menakem: And that’s the piece that I’m trying to get people to understand, and specifically white people, is that you’re gonna have to build culture and community to be able to hold this. Your niceness is inadequate to deal with the level of brutality that has occurred. Your niceness — I’m glad you’re nice to me. But don’t attribute that niceness as embodied antiracist practice.

That’s why I put the practices in there. And so that is a very important place that I think white bodies get to, sometimes, and they either genuflect to process or strategy, and then they never —

Tippett: “How do we get rid of this?”

Menakem: That’s right — “I’m gonna get rid of it. I’m gonna go do some yoga, I’m gonna eat a whole bunch of kale.” [laughs] But “I’m gonna do this thing…”

Tippett: I did yoga. [laughs]

Menakem: But you see what I mean? Then the rep is to come back, specifically around race — come back to it.

Tippett: You have this image in your work that part of our civilizational work, our national work, our political work, is to each of us settle in our bodies in a new way. And then the image that I love is that we have to settle in our bodies together, collectively.

If I asked you to — and you have different exercises for Black bodies and white bodies and police bodies, but would you just kind of demonstrate, for people who will be listening, haven’t read the book, don’t know what we’re talking about, a beginning exercise? And it could be a couple of beginning exercises, for different kinds of people.

Menakem: I’m just gonna tweak the language a little bit and call it practice, because “exercise” is, I’m gonna do it one time or something, but “practice” is, I’m gonna keep coming back, because I want to get better.

Tippett: Also, you talked about how your mother and your grandmother, again, how they just modeled this for you, that there is no failure, there is only practice.

Menakem: So in terms of a practice, this is a very simple practice (Link to share this practice). If you’re listening to me right now, one of the things I want you to do is I want you just to sit for a second. And I want you just to stare straight ahead. Just look straight ahead. And as you’re looking straight ahead, just notice what is actually landed and what is actually still kind of in the air.

All you’re doing is just kind of noticing what’s happening: noticing how much you dislike my voice; noticing how much you dislike, or you like, some of the things that Krista said. Just notice those pieces. Now what I want you to do is look over your left shoulder, and use your neck and your hips — so turn, and look over your shoulder. And then come back to center, and now look up. And look down. Come back to center. And now look over your right shoulder, using your neck and your hips. And the reason why you use your neck and your hips is that I want you to engage that psoas and engage some parts of the vagal. And then now come forward. And now just be quiet and notice what’s different.

What’d you notice?

Tippett: Well, I was kind of aware that I was half-thinking about what was gonna come next. But I don’t know, I felt more settled. And there was also a feeling of — there was kind of a feeling of comfort.

Menakem: So one of the things about the animal part of the body is that even though me and you are in this room, this nice place, there’s a part of the body that’s saying, “Yeah, but what else is gonna happen?” And the reason why — especially when I’m working with bodies of culture, one of the first things I have them do is orient, just like, orient to the room. Not orient in a mystical way, but actually, literally — because many times, the bodies of culture are waiting for danger. Even though you know nothing’s behind you, letting the body know it actually helps some pieces.

Now, if you get reps in with that, not just do it one time or just when I tell you to, what you may notice is that you may have a little bit more room for other — literally, for other things to happen that can’t happen when the constriction is like that.

Tippett: That makes sense too, in terms of how trauma is in the eternal present — you’re not remembering it, it’s reliving itself. And you’re getting — just for that minute, you’re actually settling in the real present.

Menakem: That’s exactly right. And then the body goes, oh, you mean that’s there too? And then your body starts to do this thing where you go, “Well, I don’t want to do that no more.” And then, if you can get another — there’s a thing called the reticular activation system, the RAS, that it’s the thing where, when you go buy a car, and you say, “Man, this is a beautiful car. Ain’t nobody else got a car like this, that’s this color,” and then you drive off the lot, you go down five blocks, and you’re like, “Damn, that’s the same — damn, that’s the — everybody got this car.” It was always there, but now, because your brain has said this is important, it makes it —

Tippett: You see it everywhere.

Menakem: You see it everywhere. That’s why the reps are so important, because when you get the reps in, if you get the reps in around race —

Tippett: You can do this everywhere.

Menakem: That’s right. That’s why the reps around race are so important, is that because as you get more reps in about it, all of a sudden other things start to become important that weren’t important, because now your brain is saying, “Oh, I need to read that. Oh, I need to pay attention to that. Oh, I need to track her body. Oh, I need to understand that. Oh, I need to ask questions about …” Right? And now those things become attracted to you, which creates more angst, which forces you to transform.

[music: “Tiny Water Glass” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today with clinical therapist and trauma specialist Resmaa Menakem.

[music: “Tiny Water Glass” by Blue Dot Sessions]

It feels important to me right now, at this moment in our life together — there’s a lot of judging other people, or thinking, “Can’t they just get their act together?” or “Can’t they just see the truth?” “Can’t they just hear the facts?” And it happens on every side. And something that you know and that you articulate so well is that the vagus nerve also is about safety; that the core of us, the core of our bodies, is always asking, first, “Am I in danger; am I safe?”

Menakem: Absolutely.

Tippett: And that if we don’t — you really explained this to me in a new way — that if we haven’t dealt with that, the facts will not penetrate even if they have sophisticated words to put around it and strategies, as you say.

Menakem: That’s the missing piece, is that we think, “If I can just think about this differently …”

Tippett: [laughs] Right.

Menakem: “… then that is in some way gonna make it so we can all sing kumbaya together.” And this is why I don’t — when I do my workshops and I do my experiences, I do not slam white bodies and bodies of culture together, because it is unsafe. And we all know it.

Tippett: So some of the ways we’re trying to work forward, we’re actually making ourselves unsafe again?

Menakem: We’re hurting each other. We’re re-wounding each other. Some of the things that we go to that are “supposed to” help and “supposed to” heal, really are re-wounding and are violent. There is a constant need to suss out whether or not I’m safe with this white woman or this white man or this structure. And so those types of things need to be handled and taken care of with the amount of legitimacy and the amount of care that they should have. And to slam people in the room, given the histories that our bodies have experienced, and just slam people in the room willy-nilly and then say, “Let’s talk about race,” means that you are not giving the respect to the issue of race that it deserves.

Tippett: One thing that occurred to me, reading your work, is one reason that elders are so comforting and healing — and children understand that — is because — not everybody becomes an elder; some people just get old …

Menakem: That’s right. [laughs] That’s real talk.

Tippett: … but if you get older and wiser, even a little bit, you settle into your body. You’re just more integrated.

Menakem: You’re just more there.

Tippett: There’s a line from you, which really is what this all comes down to — which is just so kind of [laughs] sad to think that this is basic human reality — that “all adults need to learn how to soothe and anchor themselves rather than expect or demand that others soothe them. And all adults need to heal and grow up.” And so many of the things we’ve done in this culture, especially around the invention of whiteness, allows people to avoid developing the full range, or inhibits people from developing the full range of being a grownup.

Menakem: That’s the piece that I think gets missed — and I’m so glad you read that — that gets missed in that book is that when it comes to race, specifically white people not understanding and not getting in and doing the cultural work that needs to be done, actually makes you more immature. So that’s a lot of times why, when a white person comes to a person of color and tries to whitesplain about race and what should be happening, that’s why people of color go … Like, “Are you out of your mind?” People of culture like, “How do you even get the temerity to try and explain that to me?” And so that’s the piece that there’s a level of immaturity. It’s like having my 14-year-old son try and tell me something about life. I’m like … [laughs]

Tippett: Well, it’s also like the origin of that term “mansplaining.” It’s the same way that relations between men and women haven’t been grown up.

Menakem: Exactly right. Exactly right.

Tippett: And again, I just want to reiterate, you start with things that are maybe uncomfortable but not hard to do, like: Put yourself in situations. If you’re a white person, go someplace where there are gonna be a lot of Black bodies, and just feel what happens in your body. And then go back again.

Menakem: That’s right. And then, once you —

Tippett: And it could be a church service.

Menakem: That’s right. And then once you get home, pause. The pausing is the most important thing. Pause. Sit with it. Notice the rage. Now, there are gonna be some people that are listening to me that say, “Well, I …”

Tippett: “I don’t have rage.”

Menakem: “I don’t have rage.” Watch. Notice that one of your ancestors may show up, not as an image, but as a sense.

Tippett: And what about a person of color? An exercise, like a starting — what would you name?

Menakem: Well, that’s a big one. So one of the things that I would say is, for people of culture, is — and this is similar to what I did that’s more for general — whenever you go into a room, even if it’s in your own house: stop. Use your neck and your hips, and look around. And pause.

Given our experience, in terms of Indigenous people, given our experience, in terms of Black people, there has been real things that have happened to us from behind. Getting whipped, having to run, having to fight, all of those pieces, there’s a stuckness that can happen in the body that gets passed down. And by the time you get it, you just have a notion of it. It’s energetically some notion. And what just the orienting does is allow you to go, OK, I’m not crazy, because my body just did something that it wasn’t doing before I did that. That’s it.

Tippett: There are so many other things I — so many other things.

Menakem: [laughs] Have me come back. I’d love to come back.

Tippett: It’s amazing. If I ask you, through this life you’ve led and this knowledge you’ve taken in and that you teach people, how would you start to answer the question about how your sense of — your sense of what it means to be human, how that is evolving, how you’d start to think that through right now?

Menakem: I think what it means to be human is to realize that we’re ever-emerging and that that — that we are not machines. We are not flesh machines. We are not robots. We come from and are part of Creation, and that that cannot just be something we talk about when we go to a yoga retreat — that it has to be a lived, emergent ethos and that — one of my ancestors, Dr. King, talked about how when people who love peace have to organize as well as people who love war. And for me, what that means is that it’s about work. It’s about action. It’s about doing. It’s about pausing. It’s about allowing — the reason why we want to heal the trauma of racialization is that it thwarts the emergence. So let’s not do that. Let’s condition and create cultures that will allow that emergence to reign supreme so that the intrinsic value can supersede the structural value.

Tippett: One of the things you — this was one of the five anchors for moving through clean pain — the first one, Anchor 1, was: Shut up.

Menakem: Shut up. Pause. Just shut up.

Tippett: And that’s just about learning to check our impulses.

Menakem: That’s it. All of your intelligence, all of the smart things you’ve done — this is one of the things that happens with me when I come off the stage and I’m doing like, a book signing. One of the first things that happens is that white people will invariably come up to me and start rolling out their racial resume: “Well, you know, I marched with such-and-such. And you know, I did this, and you know, I did that.”

How would I know that? How does that matter to people of color in your community? Show me how — operationally, not because you’re rolling out your racial resume. And so that’s where the shutting up comes into play. Just stop. And notice what’s fueling that need to roll out that resume. Where does it land? Where is it coming from? Just work with that, first. And then, when it becomes too much, back out of it, leave it alone, and then come back to it again later.

[music: “Wasto Theme” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: Resmaa Menakem has a clinical practice in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and teaches and presents widely. His books include the New York Times best-selling My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies.

[music: “Wasto Theme” by Blue Dot Sessions]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt, Gautam Srikishan, and Lillie Benowitz.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality; supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project.

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

The Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

And the Ford Foundation, working to strengthen democratic values, reduce poverty and injustice, promote international cooperation, and advance human achievement worldwide.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections