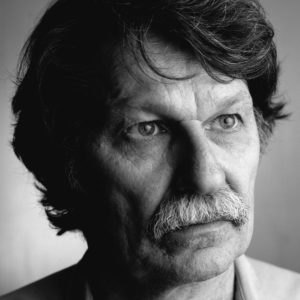

Gregory Orr

Shaping Grief With Language

We often explore on this show the places in the human experience where ordinary language falls short. The poet Gregory Orr has wrested gentle, healing, life-giving words from extreme grief and trauma. And right now we are all carrying some magnitude of grief in our bodies.

Image by Priscilla Du Preez/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Guest

Gregory Orr is the author of two books about poetry, Poetry as Survival and A Primer for Poets and Readers of Poetry, a memoir, The Blessing, and twelve collections of poetry, including How Beautiful The Beloved and The Last Love Poem I Will Ever Write. He taught at the University of Virginia from 1975 to 2019, where he founded the university’s Master of Fine Arts program in creative writing.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: Gregory Orr is a poet and a teacher on how language can become a tool for carrying what feels unbearable. When he was 12, on a first hunting trip with his father he accidentally shot and killed his younger brother. Yet he has wrested a lifetime of gentle, healing, life-giving words from one of the most terrible traumas imaginable. And right now we are all carrying some magnitude of grief in our bodies.

Gregory Orr: We ordinary people, in our daily lives, we experience enormous amounts of disorder and confusion. It’s inside us. It’s in our past. It’s in the unknowable future. And we just navigate our lives with this kind of interplay of disorder and order. And what poetry says to us is, Turn your confusion, turn your world into words. Take it outside yourself into language. Poetry says, I’m going to meet you halfway. You just bring me your chaos. I’ll bring you all sorts of ordering principles.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Gregory Orr is the author of over a dozen books of poetry and prose. He is a poet in the lyric tradition — the poetry of emotions, often in the voice of individual experience, which also lends itself to song. I met him at the 2018 Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival in Newark, New Jersey.

[applause]

Tippett: I was thinking, as I was getting ready to speak with you, about how human beings become wise, sometimes, by discovering things no one had ever known before. And sometimes we become wise by remembering and rediscovering things that people knew forever, once, and then we forgot. And I’m aware, in the circles in which I move, of this really unexpected movement of our time, often led by young people, by millennials who are claiming grief and loss and death as human experiences. And there are things called Death Cafés and The Dinner Party, which is a movement and is founded by people who had terrible loss in their early lives, and there was no place for them to talk about that in the world. And so what they want to do is claim grief and death as something that’s — not to pathologize it, but as a part of life that we reckon with and show and can accompany others in and be accompanied.

Orr: Yes. Fascinating.

Tippett: Yes, it’s fascinating.

Orr: And bring the griever, the person who’s lost, back into some form of human community. It sounds fascinating. I’d need to know more before I could comprehend it. [laughs]

Tippett: Yeah. I thought about it, obviously, because an origin point and really enduring focus of your poetry and of you becoming a poet was with this terrible, terrible death and loss, which was your younger brother’s death. You were on the cusp of adolescence and, as you said, you were a kid, “participating in a popular American ritual, hunting, firing a gun, becoming a man.” And actually, I’m not going to ask you to read the poem that — in every interview I’ve seen, everybody hands you this poem right at the beginning, which begins, “I was 12 when I killed him.”

And I just — we’re going to talk about that, but I kind of just want to start someplace a little softer.

Orr: Good.

Tippett: I mean, I think small talk has a purpose: to ease us into other conversations. Like, just, where did you grow up?

Orr: I grew up in upstate New York, rural Hudson Valley. We had one stoplight, two drugstores, one jukebox in the dark drugstore, and seven or eight churches. My father was a country doctor, so we lived out in the country. And as you say, one of the rituals, one of the realities of that world — there are two realities, I guess. One is going to church, and the other is going hunting. There must be other ones too as well, but that’s where I grew up.

Tippett: You’ve often said that you lost your faith on the day your brother died. And partly, or certainly, a huge piece of that were the platitudes that came at you: “He’s with Jesus now,” or “Somehow, everything has a purpose.”

I do wonder if there was a religious or spiritual background, however you might define that now. It seems like so much of that was swallowed whole for you by that event, but is there anything there that, perhaps at this remove, you think of when I ask about the spiritual background of your childhood?

Orr: Sure. I wish I could locate something in relation to the religious background that I had that provided consolation, and I will come up with something at a certain point. But as you say, what I experienced on that day was what I would call premature consolation, which is the moment where somebody tells you, “Oh, this is fine — your brother is in heaven.”

But I did actually have some consolation from the religious background that I had, which is to say that stories are sustaining structures. Suddenly, all the meaning was taken out of my life by this inexplicable experience, which was also something I was at the center of, but there was a story: Cain kills Abel. There you go. So there’s the consolation of story. I knew who I was, even as I entered a world where I understood nothing and seemed powerless.

But Isak Dinesen, the Danish writer, has a wonderful saying that I think is true. She said any sorrow can be borne if it can be made into a story, or a story can be told about it. I’ll go to the consolation first, and then I’ll go to the despair.

The consolation was, OK, Cain lives. He begs God to kill him, and God says, no, that would be too easy. That wouldn’t do the lesson. You’re going to live. And you’re going to live in shame and isolation and at the fringes of all human worlds. And I thought, well, that’s it. That’s what I’ll do — because I didn’t want to die, not at that point. I wanted to live, but you can’t live in a world without meaning. To be Cain is, obviously, also grandiose, but children are grandiose, aren’t they. They do think they’re at the center of some story, even if it’s a bad one.

Tippett: And you said somewhere that you lived for four years after your brother’s death without any hope at all. And then you met Mrs. Irving, who helped you work with words in a whole new way. That premature consolation was actually a careless, careless use of words, wasn’t it?

Orr: Well, I think everybody in my immediate environment that day was looking deeply into the world of terror and horror. And I think anybody who could reached as quickly as possible for some reassurance, some understanding, some ordering.

You can’t live without meaning. And I think there were two paths I found to meaning. One was writing, through the guidance of this teacher. The first, other path, for me, was social activism. So when I was 18, I went to Mississippi to work as a volunteer and just ended up getting arrested and beaten and kidnapped by a murderous individual — and that adjective is an accurate, not hyperbolic term.

Tippett: A law enforcement official.

Orr: Yes, Hayneville, Alabama. A month after I was there, this same person who kidnapped me off the highway murdered a theology student, Jonathan Daniels. And then I decided, poetry was a safer path to meaning.

[laughter]

I’m sorry. I mean, really, to go from an individual trauma to the world of social trauma, political trauma — educational, but …

Tippett: I kept thinking, also, reading you, about this phrase of the rabbis, that words make worlds.

Orr: Beautiful.

Tippett: And I feel like that’s one way to talk about how you’ve leaned into words and poetry, as survival and salvation.

Orr: Absolutely. Absolutely. What we’re talking here is lyric poetry, right; we’re talking the voice of the individual self.

Tippett: But even to name, say “lyric poetry” — so let’s talk about that —

Orr: Let’s talk about the rabbis. That’s so beautiful. [laughs]

Tippett: And so true.

Orr: “Words make worlds” — because it’s true. One of the first things I discovered, what made me a poet the moment it happened, the moment I wrote my first terrible poem, was the discovery that language in poetry is magical language. It creates a world. It summons a world into being. And that’s astounding. It’s not descriptive. Prose becomes persuasive and interesting to us when it’s vividly describing an inner or an outer world. And more power to it. But the existential necessity of poetry — lyric poetry and song — emerges from the magical power of language to create worlds that dramatize both our experience of disorder and our need for order — vividly present, both.

[music: “Detox 8” by Chris Beaty]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, with lyric poet Gregory Orr.

You like to quote Helen Keller, who, because of being born blind and deaf, she discovered language in a different way than most.

[Editor’s Note: Ms. Tippett’s statement about Helen Keller is inaccurate. Helen Keller became blind and deaf after contracting an unknown illness when she was 19 months old (source).]

It was a cathartic moment, and you quote her in saying, “We walked down the path to the well-house, attracted by the fragrance of the honeysuckle with which it was covered. Someone was drawing water, and my teacher placed my hand under the spout. As the cool stream gushed over my hand, she spelled into the other, the word ‘water,’ first slowly, then, rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motion of her fingers. Suddenly, I felt a misty consciousness of something forgotten — a thrill of returning thought; and somehow, the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that W-A-T-E-R meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free.”

Orr: There it is. It’s so beautifully primal. Here, in one palm, is the water, flowing over it. Here, she’s spelling out the word, “water.” Helen Keller was seven, and she understood this sign thing, in the sense that she understood her teacher was doing it, but she didn’t have any idea what it meant or what its purpose was. And then, suddenly, they came together, and as she said, it was like language was a form of seeing, for her. And something as essential and existential as that seems, to me, to reveal what we’re talking about, as to what language in a poem can do.

Tippett: And I think, because language is something most of us — it’s all around us from the very beginning; it’s ordinary — she, because it was hidden to her in some ways, she experienced that magic in a way that we don’t. You experienced it, also, coming out of trauma —

Orr: She’s a beautiful example of it, but we see it with children too. I love when a child is just starting to get the mystery of language, and there it is, that four-foot walks into the room, and the kid goes, “Doggie, doggie, doggie.” And you look at their face, and there it is: pure joy. It happens to be a cat.

[laughter]

What matter? What’s happening is, that word and that creature are coming together, and the child’s alive with it.

Tippett: There’s a poem in Concerning the Book That Is the Body of the Beloved where, actually, you are paraphrasing the rabbis: “Let’s remake the world with words.” Want to read this one?

Orr: Yes.

Tippett: That’s you.

Orr: Yes. Of course, one of my rabbis would be Wordsworth, the poet.

“Let’s remake the world with words.

Not frivolously, nor

To hide from what we fear,

But with a purpose.

Let’s,

As Wordsworth said, remove

“The dust of custom” so things

Shine again, each object arrayed,

In its robe of original light.

And then we’ll see the world

,

As if for the first time.

As once we gazed at the beloved

,

Who was gazing at us.”

Tippett: And of course we’re talking about poetry. But, really, we’re talking about life.

Orr: [laughs] I hope so, yes.

Tippett: We’re talking about how poetry — what poetry works in us, what it gives voice to.

In September, 2002, which I guess is when you published this book — is it Poetry as Survival — you wrote a piece, actually, reflecting on the — it was the first-year anniversary after the September 11 terrorist attacks. And you talked about lyric poetry, and I think that distinction is important, that using that, making that distinction. And again, and it’s very much about speaking to the human condition. So talk about the personal lyric as a poetic form that helps us to live, especially in crisis. And what you’re distinguishing there and talking about that really has to do with all of us, and not just the poet.

Orr: Well, it seems to me, I could begin in any number of different places, but probably I should begin, in a sense, autobiographically. We’ll anchor from that and go outward. My experience of trauma was — as a 12 year old, was, there’s the board with the game pieces on it, and in one gesture, all the pieces are scattered off the board. But it’s such a powerful gesture that the board itself is erased. There’s no longer Chutes and Ladders, CLUE, Monopoly, whatever game you want, checkers, chess. The pieces are gone, but the board itself is erased, as well. It’s just a blank. This is the abyss. This is the world of no meaning. And of course, with trauma, you also get this threat to the integrity, not just the meaning of the world around you, but the integrity of the self is also threatened, even destroyed. What we know about trauma is that it shatters us.

But let’s step back from that into just the ordinary, beautiful world of lyric poetry and what it’s there for. Lyric poetry being song, it’s in every culture, every time.

Tippett: You said it’s also Gershwin, Dylan, and hip-hop.

Orr: Absolutely.

Tippett: It’s ancient, and it’s all these new forms.

Orr: Yeah, you know, there’s this silly, dumb debate that used to go on when I was young a million years ago, about, “Is rock ‘n’ roll really poetry?” Well, the Nobel Prize committee solved that for us. OK, Bob Dylan, there you go. Let’s stop talking about that and talk about something that matters.

But what seems, to me, the reason — what’s so beautiful about lyric poetry is that what it does is, we ordinary people, in our daily lives, we experience enormous amounts of disorder and confusion. It’s inside us. It’s in our past. It’s in the unknowable future. So disorder is a part of our life. We all know that. We also know that we need order, that some kind of patterns reassure us: the sun rising, the stars and the moon, the seasons, our personal habits, which I love, the habit that reassures us about the world. And we just navigate our lives with this kind of interplay of disorder and order.

But a person in crisis, an individual in crisis, is someone who has been bowled over by some kind of crisis. And what poetry says to us is, you know what? Turn your confusion, turn your world into words. Take it outside yourself, into language. And poetry says, I’m going to meet you halfway. You just bring me your chaos. I’ll bring you all sorts of ordering principles. I’ll bring you story; if you want sonnets, I’ll bring you sonnets. What we’re going to do is, we’re going to let your crisis shine through this ordering principle.

Tippett: There’s something you say about this — I just want to say — so, somewhere, you said — right, so there is this order and disorder that we’re always straddling; and somewhere you said, what the words can do is, it doesn’t change the disorder; it holds the disorder, which is the opposite move of, yes, well-meaning people who want to say to anyone in a moment of crisis, somehow, it’s OK. Somehow, it’s OK. Somehow, there’s sense to this, instead of saying, hold this. Be there.

Orr: Yes, hold this, in the way that, probably, young people who are traumatized, they don’t want words. They want to be held, and that holding — the word, the poem, holds it, and yet, has taken it outside of you and has made it a thing in the world. It’s given you — you’ve restabilized yourself by writing a poem.

Tippett: Yeah, you said, “restabilizing the self.” Somewhere, you talk about how — that we have very sophisticated and well-worn ways to not do this, to not hold it. One is, can be, a simplistic religious way: Somehow this is God’s plan. And then, the philosophers will often ask us to “rise above it” — the rational Western tradition somehow thinks you should also be able to rise above it. On September 11, our president told people to “go shopping” — that’s another thing we do; I’m adding that to your list. There are ways we — [laughs]

Orr: Let the record show …

Tippett: [laughs] But then one thing you point out about what is missing in those ways we deny and try to get around grief and crisis and loss is, “The personal lyric clings to embodied being, insists that we stay in our bodies.” And one of the things you also said about that terrible day when your brother died, when you accidentally shot him on that hunting trip which was supposed to be a rite of passage was that you understood that — and this is what happens — families fall apart after experiences like this — that there’s this need we have to blame and somehow not take in that this is an extreme version of the fact that being an embodied — being a human being, living in a body, has jeopardy involved.

Orr: To be a human is to be continually at risk. Risk is our existential condition. None of us knows what’s going to happen next.

One thing I’d say, also, about the consolations of philosophy and religion is that they all ask us to put our personhood off to the side. As you say, embodied being — we are embodied beings, individually. What I love about poetry, lyric poetry, is, it says: It’s not God’s plan; it’s not “have a detached philosophical attitude” — it’s you, as an individual being, can make a poem or read a poem that will honor your individual identity, or your existence.

What’s beautiful about a poem is that you take on this chaos and this responsibility, and you shape it into order and make something of it. Emerson says, what we need to be is “active souls.” And certainly, when you make a poem you have become an active soul. When you’re a victim, you’re a passive experiencer of whatever it is that’s happened. But to turn your world into words and then shape that is to become an active soul. And it’s just as true about reading as it is about writing. Again, Emerson says there is creative reading as well as creative writing.

I think what we do is, we read, we look — when we’re reading poems, when we’re listening to songs — we’re looking for the things that will sustain us. We’re trying to creatively — in creative reading, we’re trying to find what it is that’s true and deep and sustaining our spirits and the dignity of our own world. Again, Emerson, he says to himself, somewhere, he says “Make your own bibles” — gather together all the poems and fragments and stuff that have shaken your spirit and sustained it. Create your own bibles. That’s a job that we have, it seems to me.

Tippett: Is there a poem you’re thinking of, as we’re speaking, that speaks to this?

Orr: Gosh. He goes blank.

Have you got one? [laughs] Show me those books over there. I’ll see if we can find something. There must be something. I will say this about that — there’s this book that I wrote called Concerning the Book That Is the Body of the Beloved. It’s a sequence of poems. It just goes on forever. I think there are about 600 of them now. But the word “book,” for me — well, I should say that this phrase appeared in my head one morning: “The book that is the resurrection of the body of the beloved, which is the world.”

I immediately knew what the phrase meant, and the book — I capitalize it in the poems about the book — it’s not a bible; it’s not a spiritual document in any ordinary sense; it’s a humanist, secular document. It’s the anthology. It’s Emerson’s “make your own bibles.” It’s your own — what do they call it? — playlist. Yeah. Let the record show, he’s in the 21st century.

[laughter]

It’s your playlist and what sustains you.

But it’s not a resurrection of the beloved in any other world beyond. It’s us, living our lives sometimes as if sleepwalkers if not alive. It’s nothing Christian. But I don’t mind saying why —

Tippett: Here — here’s actually one I wrote down — it’s short — from Concerning the Book — which speaks to what you’re saying: “Saying the word / Is seizing the world. // Not by the scruff, / Not roughly, / But still fervent. / Still the fierce hug of love.”

Martin Farawell said of this book of yours, “If Bashō, Rumi, and Rilke could somehow have a child together, I imagine they would write poems something like these.” [laughs]

Orr: What does Martin Buber say? He says, “hallowing the everyday.” This is what language can do when it recovers from the abyss of meaninglessness. It can affirm the world. It can bless the world.

Tippett: There’s the poem by Robert Hayden that ends, “What did I know, what did I know / of love’s austere and lonely offices?” You quote that in Poetry as Survival as having all of the elements of that lyric voice. Do you want to read that one?

Orr: Sure. It’s a poem by Robert Hayden, called “Those Winter Sundays.”

“Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

I’d wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he’d call,

and slowly I would rise and dress,

fearing the chronic angers of that house,

Speaking indifferently to him,

who had driven out the cold

and polished my good shoes as well.

What did I know, what did I know

of love’s austere and lonely offices?”

[applause]

The combination of celebration and heartbreak is — it’s just — it’s overwhelming in that poem, to me. And the incantatory consolation of language: If you say, “What did I know of love’s austere and lonely offices?” — hm, means something. But if you say, “What did I know, what did I know of love’s austere and lonely offices?” — that incantatory repetition, it goes into our hearts, and it changes our voices. You cannot say the same phrase the same way in human speech. You change it. You seek some other nuance in the same phrase

[music: “Room One” by New Century Classics]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Gregory Orr. And you can find this show again in three of the Libraries at onbeing.org: Poets & Poetry, Words Make Worlds, and The Body, Healing & Trauma. We’ve created Libraries from our 15-year archive for browsing or deep diving by theme — for teaching and reflection and conversation. Find all of this and an abundance of more at onbeing.org.

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today with Gregory Orr at the 2018 Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival. Much of his life as a poet has flowed out of and addressed the matter of human trauma. When he was on the brink of adolescence, he accidentally shot and killed his younger brother on a hunting trip. He writes in the lyric tradition of poetry.

I wanted to ask you — so the personal lyric is the use of the word “I.” That’s fundamental to it. I find myself curious at how — I don’t want to say — so this moment we’re in, of #MeToo and other ways people are raising their voices and their stories with a freedom that, I think, so many of us are shocked to understand wasn’t there before; and that’s part of the problem, [laughs] the realization that wasn’t there. And yet, it’s very messy. And we have to create trustworthy, more generative spaces beyond just getting the story out there. Sometimes we have to just get the story out there, but that doesn’t take us all the way.

So I’m just wondering how you — what you see might be generative and helpful, knowing what you know about words and stories and what they can do, at their deepest, for a moment like this.

Orr: Sure. Sure. So you’re asking me to go beyond the present moment, into the moment of hope and faith. OK, I’ll do my best. But I would like to pause in the awkward unease we’re feeling now and say that the story — what’s so clear with racism, with sexual assault in our culture, is that we have a culture-wide experience of — forms of trauma that are culture-wide — and that people have experienced, experience constantly. With something like — let’s say, let’s just use the #MeToo movement —

Tippett: Right, and this has been a part of the ravages of living in bodies, the jeopardy of living in bodies.

Orr: Absolutely. And nothing more informs you about the jeopardy of living in a body than the experience of trauma, whatever form that takes. Trauma is an assault on the dignity of your own being, but it’s also an assault on your body, and they are deeply intertwined. What I would say about the moment of #MeToo right now is that the stories — it’s not the stories coming out; it’s the individual people saying, “I had this experience.” That personal pronoun, reclaiming just the dignity and courage of story against huge silencing, the silencing from the culture, but also the silencing within, where we create the pathological story, which many of us use to order our lives — “It was my fault.” You see how that’s an ordering principle? “I was in control. I caused myself to be assaulted.” Patently mad, right?

Tippett: We were talking about, a minute ago, that shame is one of these things that disembodies you, in fact.

Orr: Absolutely, absolutely. It’s a survival technique, but it’s run amok. We know from many accounts that we can leave our bodies — that the person, that the child being assaulted on the bed can hover above the bed and look down. Right? We know this. We know it from testimony. It’s that shock at the center of our embodied being that frees a mind into a kind of horror ecstasy. People get drunk and take drugs, or meditate, to achieve a positive ecstasy. But we also know that the human mind and imagination can do an ecstasy of despair and horror.

Coming down into the body, coming down into claiming our stories — where we can go past those stories, we don’t know. We can slip back into the darkness, as individuals, as a culture. And so I don’t have hope, but I do recommend courage — [laughs] and voting.

[applause]

It’s a crude method, voting; it’s not — doesn’t come from the soul, but —

Tippett: No, right, well — but, I guess, here’s what I’m curious about; I wonder if you could offer some wisdom on.

Orr: [laughs] Wisdom?

Tippett: I feel like we’ve opened the floodgates to — for the stories to be told, for the “I” to be raised. But I worry that, still, that is such a tender thing, those stories that are being brought out into the world that have trauma at their root — this is trauma, finding a voice — and that the spaces in which the stories get told, this poetry of our lives is revealed — a lot of these spaces are not worthy of it. And they’re not tender with it.

I just wonder if you have thoughts about, as we move forward, how do we — these stories now, as you say, these are the thresholds. This is not the order on the other side of the chaos. This is the holding of the chaos and looking at it straight on. But do you have thoughts about how we make space, create conditions in our life together that are worthy of that lyricism of our lives?

Orr: The way forward, I think, is also through more dark. We’ve mentioned shame and the silencing, the self-blame that comes with trauma. I think another thing that scares us is rage. Those who have been harmed, one response is shame. That’s where they turn the rage in on the self. We all know that, have done that. We do it, one way we live. But you can also turn the rage outward. And that’s scary. That’s terrifying. Rage among humans, intimate rage, rage when we’re near people who are feeling rage and anger. And again, this is part of our legacy. I think what art does is, it tries to get to the place where — or, lyric tries to get to what we all share. And I think we share mysteries, but we also share passions. And passions are very, very frightening. We all experience joy. We all experience fear. We all experience anger. We all experience sadness. And we all experience disgust. That’s social psychology, I think. Some kind of experiment, some other story. But they’re the commonality for us, and anger is one of those. They won’t go away. We don’t have a solution to our passions.

What we have, and I guess this is what I would say lyric poetry does, is, we have the effort on the part of poets to both articulate their passion and modulate it into the form that we call a poem, into some kind of coherence. Whether — I think they can lead us forward, in ways — that is to say, if we can find the poems and songs that seem to show a path forward, for us. But they won’t be — they’ll be different, for each one of us.

And I think one of our spiritual tasks, in my notion of secular religion, is that job that Emerson assigns us, to make our own bibles, take responsibility for what we consider to be meaningful statements of being, meaningful in the sense that we can walk in the darkness, our own darkness, stepping, using these poems and songs and pieces of wisdom as solid footing for our journey. Where the journey is going — I’m sorry, nobody ever told me, so I couldn’t share that one — except, what is it? I’ll say this; you know what it is — the Christian thing, “a vale of tears”? A valley of tears that we walk through, or as Johnny Cash …

Tippett: The valley of the shadow of death, or the vale of tears …

Orr: And you gotta walk that lonesome valley / You gotta walk it by yourself / Ain’t nobody else can walk it for you’ — great song. I will not sing it.

But Keats, who is one of the saints in my secular religions, Keats says, oh, you know, it’s not a vale of tears. There is no other world. He says, it’s a “vale of soul-making”. And our job, as humans, is to create our own souls. And I think one of the ways we do that is by finding the songs and poems that sustain us and explain us and make us brave enough to live in this world.

Tippett: So we make our bibles, and we make our liturgies too.

Orr: Absolutely.

[music: “Perth” by Amiina]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, with lyric poet Gregory Orr.

Tippett: I think we should end with some poems of yours. I have to say, these two books, about The Body of the Beloved, they are just beautiful and wild and mysterious, to me.

Orr: Thank you. That’s a very nice thought. Hold that thought.

Tippett: And so, well, so I wrote — I have all these page numbers written down, and then I just stopped, because I — so I wonder — I don’t know. I wonder what you might want to read for us.

Orr: Oh, I thought that was your job.

[laughter]

OK — well, I will say that — not that I’m looking forward to this, but if something was going to be put on my grave, it would be short, so it wouldn’t have to be a big stone. It would be this — it would be a short poem from that: “To be alive: not just the carcass / But the spark. / That’s crudely put, but … / If we’re not supposed to dance, / Why all this music?”

[applause]

I do write short poems, don’t I? [laughs]

Tippett: Lovely. Would you read “How beautiful the beloved”?

Orr: I’d love to. Let me see if I can find it …

Tippett: Just a little bit longer — so we can draw this out.

[laughter]

Orr: None of these poems has titles.

Tippett: Right, so “[This is what was bequeathed us]”?

Orr: Ah, that’s a different one.

Tippett: Oh, it is?

Orr: You can get two for the price of one, here. I’ll read them both.

Tippett: OK, good. We’ll take two, yes.

Orr: Take two. Let’s see. “How beautiful the beloved” is … sorry …

Tippett: And would you say a little bit — this is — I know, I remember Elizabeth Alexander saying to me, it’s not that the words of a poem are true, but they get at undergirding truths. And so, ever since then, I know, to ask you what this is “about” is a nonsense question, but there’s something going on in these volumes, of you — well, it’s all kinds of things; it’s blessing and wound and trauma, and it’s love and trauma and the book and the body. And I feel like you, somehow, the beloved is somewhere, always, for you, your brother? And on, from there, other beloveds. And then, somehow, the beloved is not just a person; it’s …

Orr: No, no, no; I think, for me, when I try to think about these things, when I try to think about this term that I rely on so often in the poems — yes, my brother, my mother, both; both, deeply lost and also the wanting to bring them back because oblivion seems a cruel place to be.

The beloved can be, I think, in my thinking, my understanding of it, certainly always a person or people. We have multiple beloveds, it seems to me. Creatures: My dog is, obviously, one of my beloveds. And my cat is an off-again, on-again beloved …

[laughter]

… depending on how she’s feeling and how I’m feeling and what she’s doing. Places, I think, can be beloved; that is, we can enter into a relationship that’s deep and reciprocal and sustaining, where we give to the place, and the place gives to us. Anyway, I’m supposed to read some poems. This is two poems. This is called “How beautiful the beloved,” and it’s — again, it’s about — well, I’ve no idea what it’s about.

“How beautiful

The beloved.

Whether garbed

In mortal tatters,

Or in her dress

Of everlastingness —

Moon broken

On the water,

Or moon

Still whole

In the night sky.”

And then the other one you mentioned, “What was bequeathed us.”

I’m sure you know that “Shall We Gather at the River,” the whole sense of the other world as the other shore of the river and stuff. And this is Mr. Orr perversely reversing that.

“This is what was bequeathed us:

This earth the beloved left

And, leaving,

Left to us.

No other world

But this one:

Willows and the river

And the factory

With its black smokestacks.

No other shore, only this bank

On which the living gather.

No meaning but what we find here.

No purpose but what we make.

That, and the beloved’s clear instructions:

Turn me into song; sing me awake.”

Tippett: Thank you, Gregory Orr.

[applause]

Orr: This has been fun. I was so scared.

[music: “Long Forgotten Future” by Grandbrothers]

Tippett: Gregory Orr is the author of two books about poetry, Poetry as Survival and A Primer for Poets and Readers of Poetry, also a memoir The Blessing, and twelve collections of poetry, including How Beautiful the Beloved and The Last Love Poem I Will Ever Write. He taught at the University of Virginia from 1975 to 2019, where he founded the university’s Master of Fine Arts program in creative writing.

The On Being Project is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Laurén Dørdal, Erin Colasacco, Kristin Lin, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Serri Graslie, Colleen Scheck, Christiane Wartell, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, and Jhaleh Akhavan.

Special thanks this week to Martin Farawell, Catherine Bloch, Paul Allshouse, David Mayhew, Julia Hahn-Gallego, and the Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival and Foundation.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota Land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by PRX. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, working to create a future where universal spiritual values form the foundation of how we care for our common home.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The George Family Foundation, in support of The Civil Conversations Project.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections