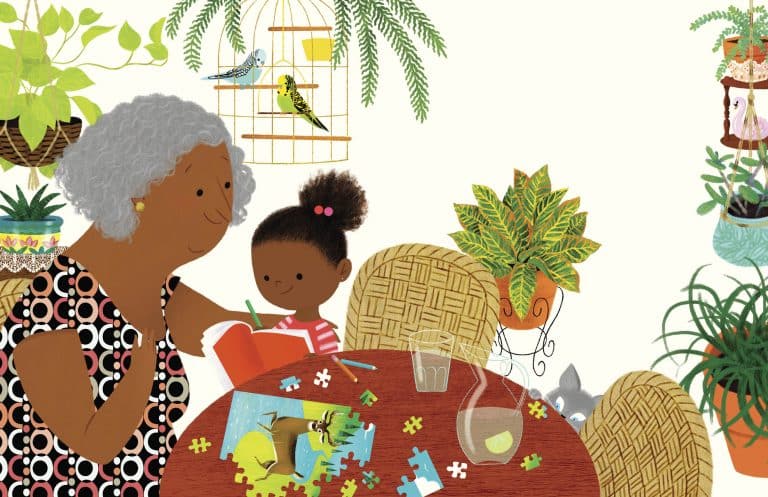

Image by Leo Espinosa/Courtesy of Dial Books for Young Readers, © All Rights Reserved.

How Junot Díaz’s “Islandborn” Brought Me Home

The year I first truly understood that I was Asian American — and not just an Asian person growing up in America — was also the year I read my first Junot Díaz book, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. The distinction seemed trivial to me up until that novel — which remains one of my favorites — showed me that it’s possible to honor where you came from, while also giving voice to the truth that growing up in America has made you something else altogether.

I was reminded of this reckoning when I read Díaz’s new (and first) children’s book, Islandborn. Illustrated by Leo Espinosa, the story follows a young girl named Lola as a class assignment prompts her to draw a picture of the country she is originally from. Lola finds herself in a predicament when she cannot remember what “the Island” — her birthplace and the book’s name for the Dominican Republic — looks or feels like. The book follows her journey to remember, as she goes around her neighborhood asking family members and friends to describe their own memories of the Island.

If I had been given the same assignment as a child, I might have had the opposite problem from Lola. Though I was born in the United States, I had a strong sense growing up that my home was also an island elsewhere — Taiwan, where both my parents grew up. Each summer when I returned to Taiwan, I was reminded of the details I had collected from the years before: The humid warmth of jetlagged dawns; the taste of mangoes that dribble on first cut; the tinny melody of the trash truck that trawls the streets each evening, singing to inform everyone of its arrival; the tenderness of my grandmother’s waist as we wove through traffic on her red moped.

I may remember the small things, but I actually feel more like Lola these days — yearning for connection to a place I’m uncertain of knowing. I’m not sure when this distance — my quiet exile from a place that was once vessel to who I was — started emerging within me. Perhaps it was in high school, when the visits started dwindling. Or maybe it began in college, when I started stumbling over my Chinese, trying to communicate my Western perspective through words that felt of another texture. Or when my grandfather passed away an ocean away from me, and my grandmother stopped cooking for the most part.

I miss the taste of her food, even the dishes I can no longer remember. I yearn for meandering afternoons spent playing baseball or swatting mosquitoes from our shins — how boredom feels different when you spend it with not just two siblings, but also four other cousins.

When I go back to Taiwan now, I find myself going through motions that, once comfortable, now fit differently, awkwardly, on me. The granite stairs at my grandmother’s house, once a treacherous adventure to climb, are now comfortably surmountable for my gait. I always expect to see my grandmother’s red moped pull up to our house, before I realize that it was totaled years ago, in an accident that she survived, and I only heard about from afar. Now, on her new moped, I feel too heavy to be her passenger. My cousins, who used to languish in summer ennui with me and my brother and sister, now make their own transient visits, choosing instead to be bored with loved ones they’ve chosen, or found — long distance girlfriends, newborn infants, in-laws I’ve never met.

The idea to write Islandborn sprouted from a promise Díaz made to two of his goddaughters twenty years ago. In the book’s dedication, Díaz includes an apology to them, among others — “To Camila, Dalia, Matteo, India, and Mai — sorry it’s late.” I too feel this loss; if only this book had been there to comfort me (and all of us) as I left childhood and the versions of reality it imprinted on me. But I also feel fortunate that it has come into the world in this moment, as I am starting to grasp for a place I once called home, to question what it should mean to me now.

What I love about Islandborn is that there is no yearning to return. Instead, Díaz seems to offer solace in a commitment to finding connection in the people around you. Lola does not talk of missing the Island, but she is endlessly curious about it: “What do you remember most about the Island?” she asks, again and again, jotting down everything she hears — ”blanket bats,” “sleep dancing,” “more music than air,” and perhaps most notably, “the Monster,” an allusion to Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo. She finds a new home in her searching.

Each of my visits back to Taiwan has felt more and more precious. Life has unfurled for me the same way it has for my drifting cousins: pulling me in different directions, not always home.

The last time I returned was two years ago, and the impending caveat that it could be my last for another few years lingered around all of my interactions. I started feeling the urge to record — capturing the sound of my family singing in the car, jotting down a list of little joys that only emerge when I return and am reminded.

One day, it occurred to me that for every time I had seen my grandmother, I had never known the story of her life. That night, I asked my mother to sit down with me and my grandmother to help translate between us: my English and broken Mandarin, with her broken Mandarin and Taiwanese Hokkien.

At the end of her day, Lola asks her Abuela of the the Island again: “Abuela, did you know about the Monster?” It is a tender moment of veiled understanding between Lola and her abuela — one that spans generations, histories, borders.

Sometimes my grandmother’s stories resurface in small moments, as I’m biking through hills or watching tofu simmer in a pan. Other times, I try to recall my scant learnings of Taiwanese history, retracing timelines and events in my head or on Wikipedia. I wish this were enough to draw a clear picture of what I remember most about Taiwan. Sometimes it is. Other times I remind myself to keep searching, to keep asking.