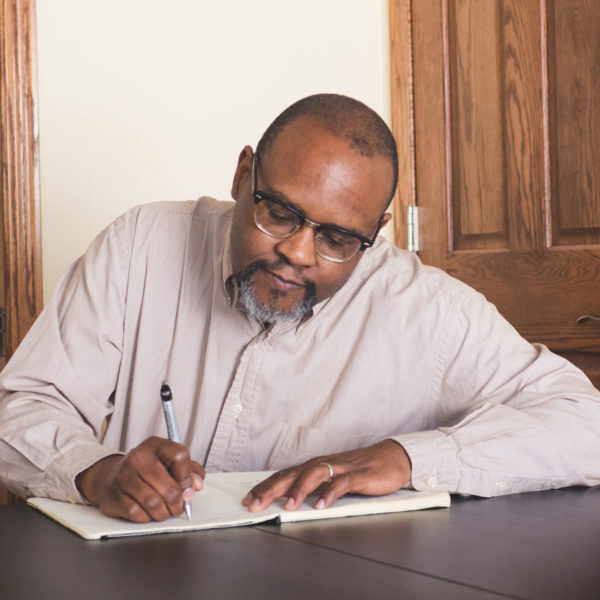

Image by Joshua Jordan/Unsplash.

My Feelings Are Not My Enemies

In one of my most vivid memories, I am about 12, standing near the dining room table at home. One of my brothers stands a few feet away, next to a pale wooden bookcase. He teases me — as he regularly enjoyed doing — about one thing or another, and in an explosion of rage, I throw a metal pointed nail file at him. In my memory, I feel terror as soon as the file leaves my hand, afraid where it might land, what it might do.

With a thump it sticks into the bookcase next to my brother. He laughs at being able to antagonize me so thoroughly, and shrugs it off, but for me it becomes the template for the danger of emotion.

As a child, I had a volatile temper expressed mainly at home, where, from my parents on down, emotions erupted on a regular basis. But that was only for private display. Anger in particular, especially for someone black and male, was a dangerous way to operate in the world, even though it was also the dominant channel of emotional expression among so many men in TV and films and in real life.

My emotional expressiveness drove me easily to both anger and tears, and I didn’t know what to do with this soft self, this permeable, thin membrane that bled feeling so easily.

I come from a family of arguers, and often was undone by the emotions swimming just below the surface of any arguments I tried to make. In part to compensate, in high school, I joined the debate team, trying to build the thickness of my rational, reasoning skin, hoping that it could protect me from the passion always so tightly attached to my values and reactions.

I don’t need to look far for the source of my opinions about emotions. Then, as now, I lived in a culture that applauds those who stay under control. I knew from school to church to what I saw on the nightly news that to describe someone as “emotional” was rarely a compliment. Then, as now, we were told that we wouldn’t be heard until we “calmed down.” Then, as now, this was a common criticism of marginalized people seeking a place at the table of power. The message was the same: the path to better decisions and solutions lay through reason and rationality alone.

I don’t deny that the search for evidence can yield information that expands clarity. But too often behind the deification of the rational lurks the illusion of certainty, as if we have (or can find) enough evidence and facts to always know the solutions. As if evidence alone can erase human fallibility.

Even scientists looking at identical information disagree about causes, significance, problems, solutions, and even whether what they’re looking at is evidence. The scientific process itself assumes a sea of uncertainty that we can only cross incrementally.

I spent much of my early adulthood caught in the gap between my emotional disposition and the calm exterior I was supposed to project. In journalism, my first field, it meant valuing cool objectivity; in academia, it meant privileging broad, all-encompassing theory (the more rationalistic the better) over the messy, felt particulars of individual lives, a messiness that was very present inside me.

Through the years, anger and sadness have warred inside me, and when I suppressed both feelings they reemerged as uncertainty and self-reproach, anxiety and depression.

No one event changed my way of thinking. I turned to medication, therapy, and self help groups. But along the way, mainly because I couldn’t escape my feelings, I began to pay more attention to them, to listen to what they had to tell me, and I started to see what my feelings did for me and not just what I thought they did to me.

I saw places in my life where feelings helped pull me off paths that intellect and rationality — aligned with conventional values — told me I should travel. I recognized emotion-driven decisions that at the time seemed disastrous — notably my choice during a deep depression to drop out of college as an undergraduate — but that eventually affirmed who I wanted to be instead of who I thought I should be.

I don’t mean that emotions are infallible or that reason doesn’t have a major place in my life. But when I attend to, rather than try to banish, them, my feelings offer me information; they provide clues that something may be wrong in the story I’m telling about myself and the world.

Over a lifetime I’ve learned the difference between feeling my emotions and indulging them, between listening to certain impulses and allowing myself to be commanded by them. And I’m still learning.

But my anger and my shame, my pleasure and my pain, my ecstasy and anxiety, my joy and my despair help reveal my values, motivations strengths and needs. If I don’t know myself I can’t know why I react to the world as I do; I can’t distinguish the fear that says I’m in peril from the fear that arises when faced with the need to change. What separates true threats to my well-being from simple discomfort at being wrong?

I’ve also come to question the division of feelings into “negative” and “positive.” We label happiness, contentment, and joy “positive.” But what do my feelings say about me if I experience joy or happiness at others being demeaned? We call anger, fear, depression, and grief “negative.” But don’t those feelings serve me when they’re telling me that something’s wrong and needs attention? And isn’t it dangerous to overlook the way culture tries to police our feelings?

I think of the educated, intelligent women, past and present, encouraged to medicate or procreate away — or simply ignore — their discontent about society’s limitations on their lives. I think of LGBT people who are told to this day that their desire for even self-acceptance is a symptom of sin or disease. I think of people of color told to overlook — or rise above with forgiveness and a smile (rather than anger) — the oppression and violence visited on them. I think of those with mental and physical disabilities told to feel grateful (rather than angry) for the crumbs they get from a culture that refuses to commit to increasing access.

Is their anger, their depression, their fear, their grief “negative”? Or is it a healthy, positive response to a culture that encourages them to devalue themselves?

Examining recently the work of the neuroscientist Antonio Damasio has deepened my sense of emotion and feelings as essential to our sense of self, and even to the ability reason. He defines emotions and feelings this way:

“For neuroscience, emotions are more or less the complex reactions the body has to certain stimuli. When we are afraid of something, our hearts begin to race, our mouths become dry, our skin turns pale and our muscles contract. This emotional reaction occurs automatically and unconsciously. Feelings occur after we become aware in our brain of such physical changes; only then do we experience the feeling of fear.”

Damasio contends that emotions and feelings are central to human consciousness and they play a critical role in reasoning itself.

“Rather than being a luxury, emotions are a very intelligent way of driving an organism to certain outcomes,” he has said. “And we know this because if you’re deprived of those emotions then, lo and behold, rather than being a sort of coolheaded reasoner, you become a rather poor reasoner.”

In my own case, my impulse to reject my emotional/feeling self was driven by the risks involved. In my family, work, relationships, and even writing, expressing feelings ran the risk of opening myself to rejection or ridicule.

The way my feelings and emotions could render me vulnerable frightened me for a long time. It seemed easier, behind a calm, reasonable veneer, to stay safe and project a dispassionate persona, wielding the shield of certainty that would keep anyone from seeing the trembling me beneath.

I don’t mean to downplay the life-and-death consequences that can come from allowing anger, anxiety, or depression to overtake me. More than once, I’ve mentally walked that path almost as far into the abyss as it can go.

But I no longer see my depression and grief, anxiety and anger, as enemies. I try to treat them as messengers sent to caution me: to remind me of the need for self care; to help me reassess and release attachments; to encourage me to reexamine values; to suggest that it’s time to revisit and revise the story of my identity. To come to my rescue.